© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Adventures of the Dream Ship

A famous author, his sister and a friend sailed a 47-

GREAT VOYAGES IN LITTLE SHIPS -

RALPH STOCK is the pioneer of modem ocean-

RALPH STOCK is the pioneer of modem ocean-

Miss Mabel M. Stock, his sister, sailed with him and showed that ocean cruising can be enjoyed and not merely endured by a woman. Brother and sister were accompanied by a friend for the entire voyage from Brixham, Devon, to the Tonga Islands. In addition, Stock had an experienced, elderly yachtsman as passenger from the Canary Islands to Tahiti, and at times there was a fifth person on board.

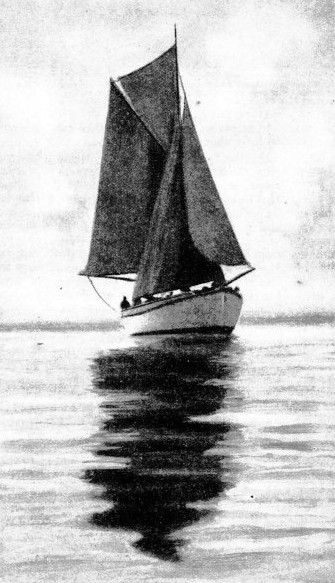

DESIGNED BY A FAMOUS NAVAL ARCHITECT. The Ogre, the ship in which Ralph Stock, with his sister and a friend, sailed to the Pacific, was laid out by the late Colin Archer, who drew up the plans of the Fram for Nansen, the Polar explorer. The Ogre had originally been built to serve as a lifeboat for the North Sea fishing fleet, and was sold to a man who fitted her out as a yacht.

A voyage across two oceans in a 47-

For years Ralph Stock had dreamed of cruising through the South Sea Islands in his own ship, and when at last he had overcome preliminary difficulties, and had bought and equipped his yacht, he naturally thought of her as his dream ship.

Stock’s seamanlike and successful cruise was the first of its kind, and was delightfully free from any effort to set up records or to be heroically uncomfortable. Stock wanted to enjoy himself as master of his own ship, and he did. He was short of money but he kept his financial troubles to himself. No water-

Thousands of people who have read Stock’s account of his trip have thought of following in his wake, and a few have tried to sail in the track of the dream ship, only to fail. It is true that many people equipped with far greater resources have tried to follow his example, but they have not had Stock’s gifts of seamanship and common sense. Sailing a small yacht to the Pacific without a paid crew is not a matter of hard cash and blind, raging sea-

Few people wish to sail single-

In estimating Stock’s feat as a seaman we must bear in mind his qualities as a diplomat. Not only did he make his voyage without undue fuss or bother, preserving his vessel from stranding or being wrecked, or damaged through carelessness, but he also preserved harmony among his two shipmates. In addition, Stock carried a passenger to Tahiti in the Ogre, although this passenger was unfortunate enough to suffer from Canary fever while on board.

THE OGRE AS A FISHING SMACK. After Ralph Stock had bought the Ogre he had little money left to fit her out for his cruise. To provide funds for the extensive fitting out, Stock went trawling, although the war of 1914-

Many accounts of ocean cruising in yachts that have needed crews to handle them contain painful references to the crew problem, and many cruises have come to an abrupt end because of it. Nothing is more embarrassing for an outsider than to go aboard a little vessel that has just reached port after an ocean passage of several thousand miles, only to find that the members of the ship's company are at loggerheads and are about to part company.

Trouble of this kind, which has wrecked so many ventures, is more to be feared than the violence of the sea. It is a tribute to Stock, to his shipmates and to his passenger that the Ogre got so far without friction.

Another point overlooked by those who think it is easy to emulate or surpass the voyage made by Stock is that he and his sister were “old hands” before starting. In 1914, with a friend and a paid skipper, they sailed an ancient six-

During his service in France in the war of 1914-

From the beginning Stock showed his wisdom. He knew the type of boat he wanted for the cruise and saw that he acquired her. The Ogre was one of the best ocean cruisers that ever put to sea, irrespective of size, and she was in the hands of a first-

The Ogre’s pedigree was of the bluest blood, her designer having been the late Colin Archer, who had designed the Fram for Nansen, the Polar explorer. Archer was one of the most gifted naval architects, his North Sea pilot cutters being a delight to the eye and a joy to the seaman. The Ogre had been designed to serve as a lifeboat for the North Sea fishing fleet, and she was sold to a man who fitted her out as a yacht. Built in 1908, she was 47 feet over all, 15 feet beam and 8 feet draught. Stock bought her in Devonshire for about £300; but she was not then fitted out for the long voyage. The war of 1914-

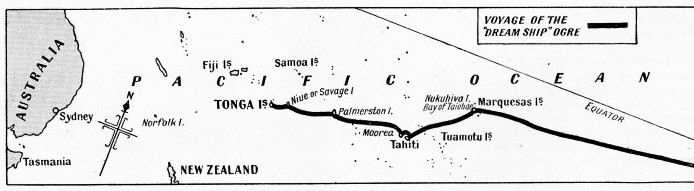

THE COURSE OF THE DREAM SHIP is indicated on these maps. The Ogre was built in 1908 ; she was 47 feet overall, had a 15-

Nothing reveals Stock’s determination more than the fact that he spent practically every penny he had in buying the ship at a time when the prospects of an ocean cruise seemed so far off. He thoroughly deserved a bargain. To provide funds for the extensive fitting out Stock went trawling. The war was not yet over, and fish were fetching high prices. To catch the fish, Stock had to risk his life and his ship, as he had to trawl over the U-

The Ogre was rigged as a cutter and had a 13 horse-

No ocean voyage began more in-

At Vigo -

This new-

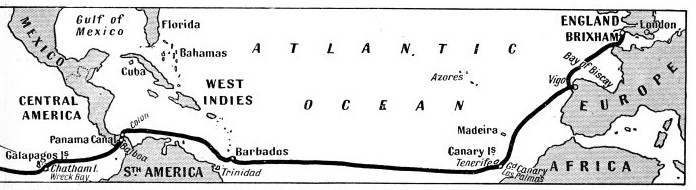

ON THE LOOK-

The three adventurers had to wait several weeks at Las Palmas for the arrival by steamer of the passenger, and they caught “Canary fever” while they were waiting. They found prices high at that time in the island and lived on salt beef and ship’s biscuits, saving the better food for the passenger. The passenger arrived and they sailed for the West Indies. Unfortunately for everybody they found that the passenger had no teeth, not even artificial ones; this complicated the cooking. He took a watch, however, and did carpentry, spliced ropes and helped in many ways.

The passage to Barbados occupied thirty-

Stock had a birthday during the passage, and his sister, with true feminine regard for the occasion, determined that he should receive a pleasant surprise. She made up a mysterious parcel of a tin of cigarettes, steamed stamps off old envelopes and stuck these on a wrapper which she addressed to her brother. To Stock’s amazement, the parcel appeared on the cabin table as though delivered by a postman.

Because of a faulty chronometer, Stock did not find Barbados where he calculated it to be, and was standing away for Trinidad when the passenger sighted Barbados. The mainspring of the chronometer broke soon after the Ogre reached the island. The next stage of the voyage was to Colon, on the Atlantic side of the Panama Canal, off which Stock had doubts as to his position. It appears that a current had carried him many miles from Colon; so he sighted a lighthouse and then joined the procession of ships making for the Canal.

The Panama Canal is a problem for every cruising yachtsman. It is such a marvel of efficiency that he dreads getting into difficulties in the middle of it, making an exhibition of himself and incurring heavy charges for towing. The Canal must lose money on every small yacht that passes through, because the charges are based on tonnage and every vessel must have a pilot. Thus the dues on a small vessel are small, and special care has to be taken at the locks to avoid damage to a fragile yacht. Stock’s main worry was the temperament of his engine. The first series of locks is at Gatun; these are always the worst for a yacht, as the three lock chambers lift the vessel 85 feet above the Atlantic to the fresh water Gatun Lake. There are altogether three series of locks, Gatun, Pedro Miguel and Miraflores. A great ocean liner or a battleship gives far less trouble than a small yacht, because a large ship occupies most of the chamber and the wonderful machinery is able to handle her. A small yacht may be compared to a matchbox in a bath of water with ants on the matchbox trying to control it as it is tossed about by water pouring in from the bottom of the bath.

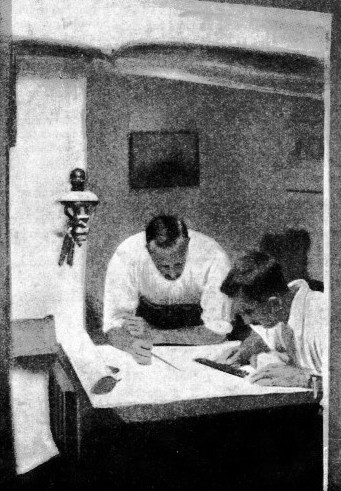

FINDING THE SHIP’S POSITION. The illustration shows Steve, Ralph Stock's friend, on board the Ogre using the sextant.

At Gatun, also, the pilot is new to the yacht and is apt to apply steamship practice to a tiny vessel that has an auxiliary engine with a propeller on the quarter. The lift at Gatun being 85 feet, the level of water in Gatun Lake is the highest in the canal. At the second lock, Pedro Miguel, vessels descend 30 feet, and at Miraflores 55 feet to the level of the Pacific. Small yachts are not “locked through” separately, but have to wait for steamers and go through with them.

When the Ogre was in the lock chamber at Gatun and the water was let in, there were several minor mishaps. The passenger, who was at the helm, was crushed between the tiller and the side of the steering wheel by the force of the water that sluiced against the rudder. As the yacht rose, her covering-

FINDING THE SHIP’S POSITION. Stock and his friend are checking the position of their ship on a chart.

The passage from Balboa to Chatham Island, one of the Galapagos group, across one of the strangest stretches of water in the world, provided one of the most amazing incidents of the cruise. These islands are not only a puzzle to the scientist because of their formation and their strange animal life, but also they baffle the mariner because of the currents. Poor visibility generally hampers the navigator in getting observations to establish his position. The Spaniards had good reason to call them the Enchanted Isles (Las Islas Encantadas).

As with many other people, Stock did not see the Galapagos until he was right among them. When he did see them, it took him some time to distinguish one from another. The engine was out of action, but a breeze came along. This faded and down came a fog. The current carried the yacht towards an islet which they could not see in the fog and darkness, and then they realized that they were alongside a precipice that shot sheer up from the sea. They fended the yacht off by hand and manoeuvred her until a faint breeze caught the idle sails and blew her clear. One roller would have cracked the yacht against the wall as if she were an egg, but the water was as smooth as a duck pond. When day dawned they were still in doubt as to their position, but Miss Stock suddenly recognized one point on the chart, and then the whole position became clear. Thus the Ogre anchored safely in the ominously -

The islands belong to Ecuador, and an Ecuadorian official who had good reasons for not visiting the mainland successfully pleaded with Stock to let him embark as cook, so that the Ogre sailed with this young man and a baby tortoise added to the ship’s company. “Bill”, however, as they called the Ecuadorian, proved more ornamental than useful.

Thanks to a good south-

The yacht did not stop in the Tua-

A DESCENT FROM THE RIGGING of the Ogre. One of the crew of the dream ship coming down after having had a look-

After she had visited Moorea, opposite Tahiti, the Ogre sailed to Palmerston Island, where the trade goods brought from England were sold to the inhabitants. The Ogre went on to Niue, christened Savage Island by Captain Cook, and then to the Tonga Islands, where, on an impulse which he afterwards regretted, Stock sold the yacht at a good figure. The adventurers then went their various ways and the cruise was over. On the last stage of the voyage the yacht had two narrow escapes. While hove-

When he entered the difficult channel leading to his last port of all Stock asked for a pilot; unfortunately the local pilot mistook his signal for a burgee, and for a long time the engine fought a strong current until the pilot woke up to the fact that he was wanted, and dashed out to bring the yacht in through the narrow channel.

When he sold the Ogre Stock intended to continue in a bigger vessel, but failed to find one that approached the Ogre. She was a well-

Dangers of Engine Failure

On the other hand, an engine that can be started easily and can be relied upon in an emergency is always worth while, because it may save the yacht from being wrecked. Some blue-

All that yachtsmen such as Stock expect from an engine is that it should enable the yacht to enter and leave port when there is no wind or when the wind is contrary, entailing a good deal of tacking before the yacht can work up to her anchorage.

During a voyage which includes the passage of the Panama Canal an engine is necessary, unless the yachtsman can afford to pay the high charges for a tow, or will wait until a small-

It is the danger of being caught in such a way that is the nightmare of the yachtsman. Several small yachts after journeys of thousands of miles have been wrecked in that way. The early navigators in sailing ships had only one chance, to lower boats and pull the ship clear by towing.

A most important principle of blue-

Stock’s feat of sailing so far without loss or damage is one of the finest in the epic of the “little ships” that to-

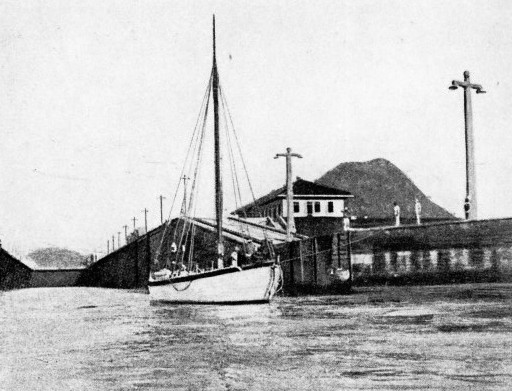

IN THE PANAMA CANAL. Several minor mishaps occurred to the Ogre while she was passing from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean through the famous Canal. The most serious of these mishaps was the breakdown of the auxiliary engine. The cost of having the Ogre towed through was so great that the rest of the voyage was in danger of having to be cancelled. About this time, however, Ralph Stock received payment for the film rights of a story he had sold. This payment enabled him to continue the voyage.

You can read more on “Great Voyages in Little Ships”, “Supreme Feats of Navigation” and “Standing and Running Rigging” on this website.