© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Fortunes Of War

Extraordinary ingenuity and daring were shown by Count von Luckner, who converted the steel square-

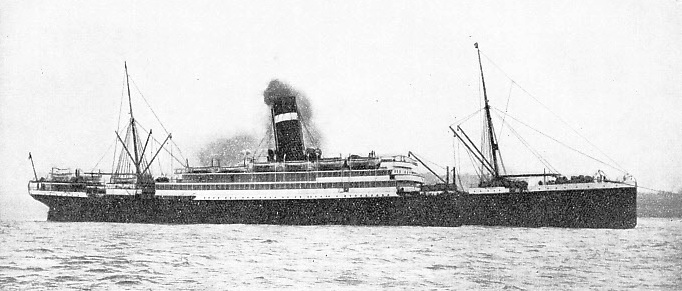

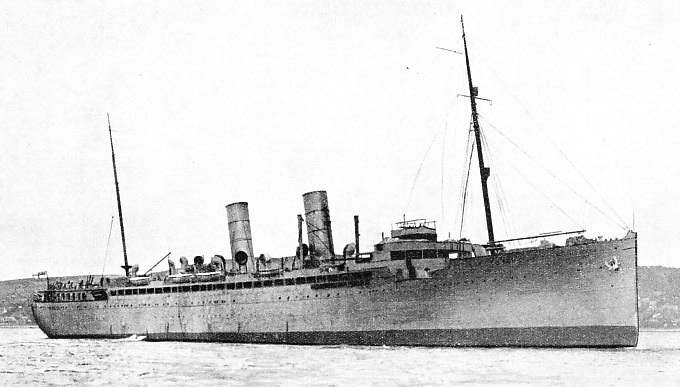

AN ARMED LINER, HMS Victorian was 2 unit in a blockading squadron off the north of Scotland during the war of 1914-

FEW stories of the sea and ships have a more sustained interest than that of the square-

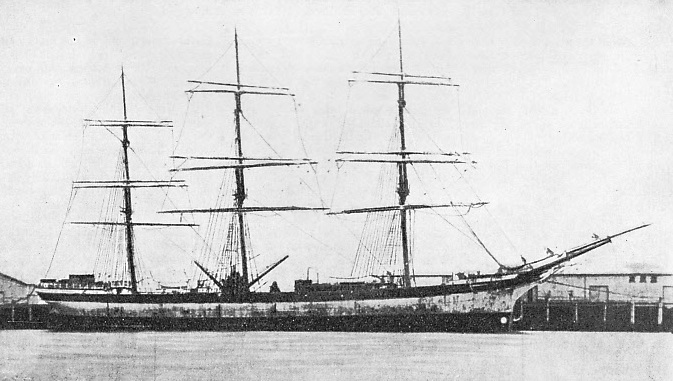

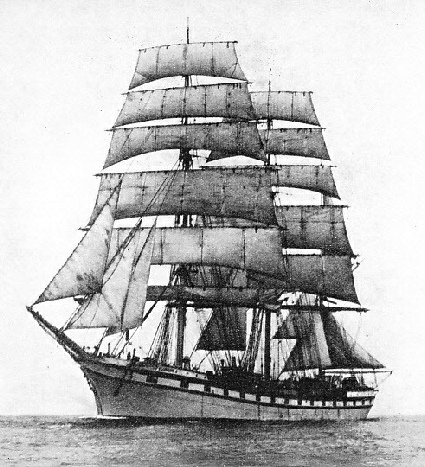

This fine sailing vessel of 1,571 tons was built on the Clyde in 1888. She and her sisters represented one of the last efforts to compete with the all-

During the war of 1914-

The British blockading squadron was made up of armed liners and other commissioned merchant steamers. A good deal of preserved food, however, and such items as cotton were unquestionably getting past and, as a further precaution, a thorough examination of neutral ships was made. As this could not be done in the open sea, the guards would bring suspect ships into Kirkwall, in the Orkney Islands, or Lerwick, in the Shetlands, where experts carried out a detailed inspection.

On June 23,1915, the Pass of Balmaha left New York with a crew of twenty and a cargo of cotton bound for Archangel, in Russia. She crossed the Atlantic without any trouble, and on July 21 she approached the blockade zone 300 miles north-

On July 19 the submarine U 36 started from Heligoland, bound through the North Sea for a cruise of several weeks. Three days later she began to make successful attacks off the north of Scotland. During the period July 22-

U 36, in command of Lieutenant-

A LIGHT CRUISER with a displacement of 4,800 tons, HMS Glasgow patrolled the South Atlantic waters during the war of 1914-

The Pass of Balmaha was in a dangerous position. If the Germans were so eager to clear the sea that the rights of neutrals were not to be respected, then this American vessel would stand a poor chance. The British officer decided to take instant action. He burned his secret orders, told his men to change out of uniform, borrow clothing from the Americans, and stow themselves in the forepeak till the crisis passed.

Graeff, however, did not sink the Pass of Balmaha that was flying the Stars and Stripes. Coming alongside about 7 am, he put on board Petty-

Germany would be glad of this cargo of cotton for the manufacture of munitions. Again the Pass of Balmaha resumed her voyage. The Englishmen reasoned that this would not continue for long. They were confident that another of the blockading units would be sighted, and that Lamm would find himself a prisoner.

Never in any naval war has a blockade been made absolutely strict. In 1915 the two principal lines of blockading steamers were so disposed that Line “C” (consisting of seven to nine ships) patrolled to the north-

First “Trap-

U 36 continued her depredations in the blockaded area north of Scotland. On July 24, nearly twelve hours after the Pass of Balmaha had sailed away, Graeff stopped the Danish steamer Louise about ten miles W.N.W. of North Rona Island. At the same time he noticed a little 373-

The collier was the Prince Charles, and on sighting U 36 she hoisted her colours. Graeff started to shell her with the purpose of making her heave-

Suddenly Graeff was surprised to see the collier’s crew clearing away some tarpaulins on deck. Before the submarine could dive, a number of shells were fired from the collier’s port side. At once the German gun-

The Prince Charles was one of the first decoy ships, and her success had no little influence on the development of Q-

THE MYSTERY SAILING SHIP that terrorized shipping in the southern Atlantic and Pacific Oceans was originally the full-

An ingenious and profitable idea of this nature is bound to be copied sooner or later by the enemy. During the ensuing months Germany resolved to follow this example with important modifications and on a larger scale. She longed to strike at the British supplies of raw materials and food in transit. Shipping convoys had not yet been inaugurated, and British light cruisers were unable to guard every section of the shipping lanes, so that any raider which could once get clear of the British Isles might for a limited period have considerable success in waylaying the traffic from South America.

The crux of this undertaking was obviously the evasion of the blockade zone. This could best be done during the season of the year when nights were longest, and when rain, fog, drizzle and bad weather were most prevalent. It might necessitate going to high latitudes where every one of these conditions of protracted darkness and bad weather was ensured. Obviously, too, December was the best time to set out.

In December 1915, therefore, the steamship Moewe left Germany, stole up the North Sea, and dodged her way past the patrols. She reached the Atlantic, and there was responsible for the destruction of ship after ship. On March 4, 1916, she was safely back in Wilhelmshaven.

This feat was largely due to the fine leadership of Captain Count Nikolaus zu Dohna-

Von Luckner was wounded at the battle of Jutland on May 31, 1916. When he recovered, weary of the inactivity that the High Seas Fleet compelled him to endure, von Luckner begged to be given command of a raiding vessel, so that he might emulate his cousin’s achievements. Approval was granted, and he went to the port of Hamburg to seek a suitable ship. There he noticed the Pass of Balmaha, and he conceived the daring project of using a sailing ship as a decoy. It was an excellent idea, for a number of once British-

The whole future of this projected expedition depended on the ship being allowed through the blockade area, and as she was to fly the Norwegian flag, it was well that von Luckner had the blond appearance of a Norwegian and that in his earlier days he had spent a year aboard a Norwegian sailing ship.

The problem of the ship’s papers was overcome by using documents that had been captured from a Norwegian ship. From the German Imperial Naval Reserve a crew was hand-

The ship’s company numbered sixty-

Special pains were taken to make the saloon seem natural, for the entire floor had been altered to form the platform of an hydraulic lift that could be lowered for a depth of fourteen feet. Thus, if the ship were to be captured by a British crew and sent under their charge into Lerwick or Kirkwall, she would never get there. Von Luckner was to wait until the prize crew were having a meal and then, at the touch of a button, the floor would drop and the captors become captive. The Pass of Balmaha would resume her voyage as the Irma.

Provisioned for three years, this vessel was bound for the Pacific Ocean by way of the South Atlantic. The sudden presence of a disguised raider on that ocean would not fail to cause perturbation. No one, even at short distance, would ever suspect an old ship with yards and sails to be a man-

The staff of the Irma had been selected with care. Her Chief Officer was Lieut. Kling, who knew South America well and had served on several Arctic expeditions. The Navigating Officer was Karl T. P. Kirscheiss, who had experience in sailing ships and had been all over the world. The mate, Ludermann, had also served in British sailing ships, and H. H. Krauss (in charge of the motor) had been engineer in a German passenger steamer.

The Irma started out for her long voyage from Bremen on December 21, 1916, the year’s shortest day, in a strong gale. Two other distinguished raiders, the steamships Moewe and Wolf, had left not long before. Heading up to the north, the Irma encountered no other ship until 9.30 on Christmas morning, when she was about 180 miles S.W. of Iceland. Here she was stopped by HMS Avenger, a 15,000-

Successful Bluff

Von Luckner kept on deck the five Germans who could speak the best Norwegian, and made a point of giving loud commands in that language. “Are you the Captain?” inquired the British officer. “Yes, Mr. Officer”, answered von Luckner in English. “Come aboard. A Happy Christmas! You wish to see my ship’s papers? Certainly, sir. Please come aft.”

In the saloon, where the fittings must not be examined too closely, reclined on a divan a seventeen-

The guns were concealed in the Seeadler on much the same principles as were employed in British Q-

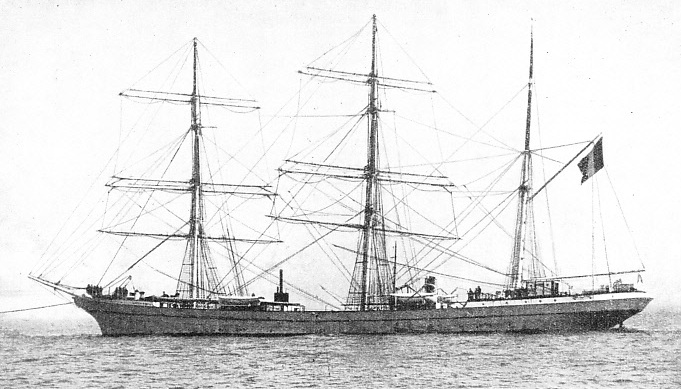

A FRENCH THREE-

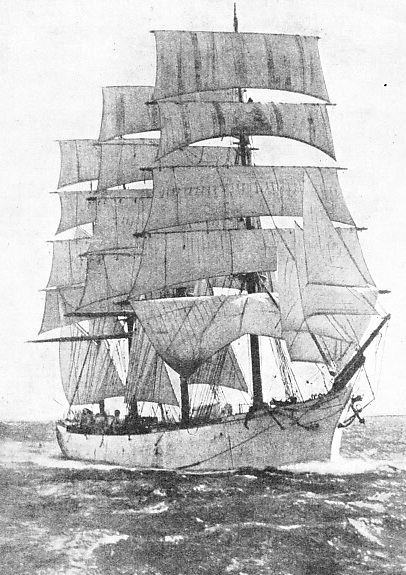

When the British barque Pinmore loomed up on the horizon, von Luckner himself boarded her as Prize Officer. The barque looked familiar to him and he walked aft to examine her steering-

It was now late in February. The Seeadler had been at sea for two months and needed fresh vegetables, fruit and tobacco. Von Luckner decided to leave Lieut. Kling in temporary command of the Seeadler and appointed a rendezvous. Meanwhile, from a position some 100 miles off Rio de Janeiro, the Count sailed the Pinmore into Rio. Her crew were mostly Norwegian, but her commander, Captain J. Mullen, was British. At Rio, von Luckner went ashore, arranged for the stores to be sent aboard, and coolly went to watch HMS Glasgow coaling. With provisions aboard, von Luckner set sail again in the Pinmore.

CAPTURED OFF RIO DE JANEIRO by Count von Luckner in the Seeadler, the British four-

Three days later he rejoined the Seeadler. The stores were quickly transferred and the Pinmore was sunk by a bomb. Then von Luckner sent a wireless message in code to his cousin Count Nikolaus warning him that HMS Glasgow was leaving to seek the Moewe. The Moewe later turned for home, ran the British blockade again, and reached Germany on March 22. The Seeadler went south and captured the French barque Cambronne. By this time the Seeadler was crowded with prisoners from various sunken ships. Von Luckner placed 286 prisoners aboard the Cambronne, with Captain J. Mullen in command, and supplied him with navigating instruments and a month’s provisions. To prevent them from arriving too soon at Rio, thereby giving away his position, von Luckner sent men to saw off the Cambronne’s topgallant masts and to heave overboard the spare sails and spars.

British cruisers were in the vicinity, and it was expedient for the Seeadler to move away. She rounded Cape Horn on April 18. Two uneventful months passed and the Seeadler, keeping 400 miles west of South America, sailed north as far as the Equator. On June 14 she surprised the United States schooner A. B. Johnson and set her on fire. Similarly she destroyed the American R. C. Slade three days later. On July 8, among the Pacific Islands east of Christmas Island, and north of the Equator, the Seeadler sank the American schooner Manila.

WITH 236 PRISONERS ON BOARD the French three-

Wreck of the “Seeadler”

The Seeadler had now been at sea for seven months and had sailed half-

Mopelia, situated on a reef surrounding a lagoon, is about ten miles long and four miles wide. As the prevailing winds were south-

Count von Luckner had arranged that if anything untoward should occur the officer in charge was to fire a gun twice as a signal for the shore party to return. Unexpectedly at 9.30 am they were alarmed by two loud reports. A sudden shift of wind from south-

The Seeadler was abandoned, her sails were unbent and taken ashore for tents. The wireless was hauled down, the dynamo and its motor landed, and the aerials stretched between lofty palm trees. Provisions were fetched from the ship, but on the island pigs and game abounded, with fish and turtle in the water.

As von Luckner had been sent from Germany to raid Pacific shipping, he decided that the loss of the Seeadler must not interfere with his work. He therefore chose one of the six lifeboats with a 7-

The little Cecilie, with a S.E. wind, steered under all sail W.S.W. Von Luckner’s intention was to reach the Cook Islands or the Fiji Islands, seize an American schooner, sail back to Mopelia, fit her out and then go raiding again. The Cecilie could travel more than 100 miles a day, though sometimes she had to heave-

The Cecilie put to sea again the same day, steering S.W. for Rarotonga in the Cook group. There they saw a large black steamer in the harbour, and it appeared to be a patrol vessel. They carried on, therefore, to the island of Aitutaki and bought provisions. Some hostile natives, led by a half-

The Cecilie hurriedly set sail and took a course to the north-

After they had passed north of Nairai, they were caught in bad weather, and on September 18 ran into the bay of Wakaya to anchor. The gale kept them weather-

Captured by Fijian Police

The Count landed and, after some inquiries, said that he was a Dane and that the Cecilie had broken down; he asked if she could be towed to Suva. He was told that a schooner had come into Wakaya for shelter, and her owner was expected in another vessel as soon as the weather moderated. He learnt, too, that this owner was of Danish nationality.

This information made von Luckner anxious. His own plan had been, once clear of the land, to slip the tow, board the schooner, make the crew his prisoners and thus get away. When, however, on the morning of September 21, the 535-

Then the Amra lowered a boat, which pulled rapidly across and headed off the Cecilie. As this boat came alongside, the Germans found themselves covered by seven revolvers almost before they had time to reach for their hidden arms. Two white officers of the Fiji Constabulary and five native policemen simply and quickly brought the bold scheme to a sudden end.

The six Germans were taken to an internment camp in Auckland Harbour, New Zealand. On December 13 von Luckner and Kirscheiss escaped and captured another schooner, but they were caught. Kling’s party on Mopelia Island had to wait only from August 23 to September 5, when the 150-

The Americans and the Lutece’s French crew were loft on Mopelia with nothing but some indifferent food and a damaged boat. Four of the Americans patched up this boat, set sail on September 19, and ten days later reached Pago Pago, the United States coaling station on the Samoan island of Tutuila. Thus assistance was obtained for the other men on Mopelia.

THE BRITISH BLOCKADE was designed to prevent vessels reaching Germany from the Atlantic. The German decoy ship Irma, originally the Pass of Balmaha and later the Seeadler, had therefore to run the gauntlet of the blockade vessels. Her commander, von Luckner, successfully bluffed a boarding party from the 15,000-

You can read more on “The Convoy System”, “Epics of the Submarines” and “Troopships & Trooping” on this website.