© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Hell Ships and Floating Homes

Life at sea was formerly a strange mixture of hardship and comfort. Some ships, because of the barbarous conditions in which their crews worked, were known as “Hell Ships”. Other vessels, even in the days when a career at sea was inseparable from hardship, were comparatively comfortable

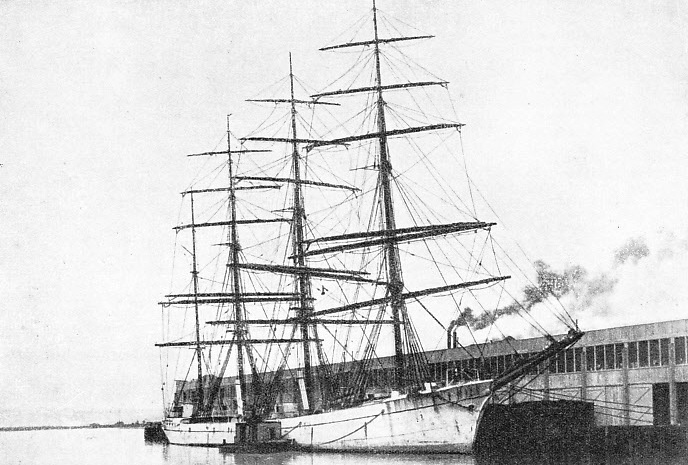

ONE OF THE MOST BEAUTIFUL OF THE LATER SAILING SHIPS to fly the American flag, the Dirigo, had a bad reputation among sailors. This ill-

THE worst blot on the fair history of sail, which contains so many magnificent chapters, is the unnecessary brutality found in so many of the old ships, even in some of the best whose names come down to us as examples of all that was finest in the old school. Nowadays “bucko mates”, “hard-

A good deal of the hardship was formerly regarded as unavoidable and inseparable from the design of many ships; this design, however, could easily have been modified, and there were numbers of owners who were always well ahead of the law. The trouble was mostly in the position and design of the forecastle. It was right up in the eyes of the ship, with the hawse-

The whole of the victualling system in nine sailing ships out of ten would be regarded nowadays as gross cruelty on the part of the owners. To save money many owners would buy stores that had been condemned by the Navy -

Sullenness begets mutiny, mutiny was the offence which the afterguard always dreaded. At a time when punishments on land were harsh, those at sea were made even more brutal. This was done deliberately, for in a small community the least sign of mutiny had to be checked for the safety of all hands. Thus many of the punishments which were officially permitted and even laid down were cruel in the extreme.

The cat-

In addition to maintaining discipline and checking any tendency to mutiny, the officers of the average old-

The brutal methods frequently won for their ships an appalling reputation, but it must be remembered that the officers had many difficulties to face. Moreover, they were always aware that a poor seaman could easily imperil the safety of the ship and the lives of those on board. The “packet rats” who largely manned these transatlantic clippers were invariably mutinous. At one end the clippers shipped the toughest crew of Liverpool Irishmen, and at the other end a sprinkling of New York gangsters. Long before newspapers and films made the world familiar with the American gangster, there existed the gangs of the New York water-

“Paddy Westers”

There were always sham seamen attempting to work their way across to the U.S.A, where they had every intention of deserting; these were known by the generic name of “Paddy Westers”. They were among the officers’ greatest curses; the “packet rats” were at least seamen who could be relied upon in an emergency.

The “Paddy Westers” were called after an Irishman, Paddy West, keeper of a low type of seamen’s boarding-

The “Paddy Westers” were called after an Irishman, Paddy West, keeper of a low type of seamen’s boarding-

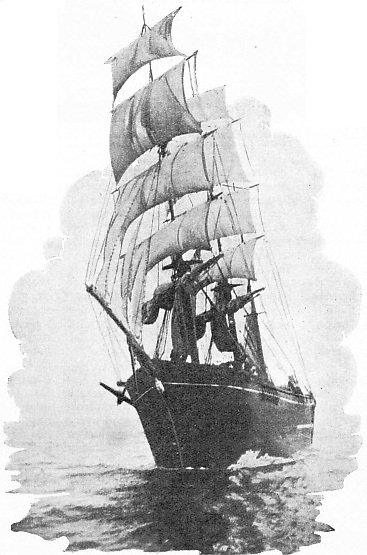

A NOTORIOUS VESSEL, known as the Bloody Gatherer. Her record for the appalling ill-

A large proportion of “Paddy Westers” in a watch, all shipped as qualified able seamen, might well cause a racing clipper, hanging on to her flying kites to the last moment, to be completely dismasted or to founder with all hands.

So the packets became notorious for their hard treatment before the steam liners swept them off the Atlantic. The Devonshire was specially noted, even in such bad company. Her captain and second mate worked together in a spirit of absolute ferocity, leaving the first mate, who was a humane man, to his own devices during his watch on deck. A man was lost overboard during the second mate’s watch. There is little doubt that it was an accident, but the American crew had already had enough, and they left the ship in a body in London, accusing the second mate of kicking the unfortunate seaman off the yard-

This matter of kicking a man off a yard when handling sail at night was a terrible one, and there is no doubt that it happened in more than one ship. It was a particularly brutal and cowardly murder, for if the man were doing his work he had no chance to save himself in a sudden attack, and once in ice-

But brutality was not universal even among the packets; some officers made a point of picking their men carefully, treating them well and signing them on again and again. These were happy ships and many of them made conspicuously smart passages. But the gangs ashore were naturally jealous and made every effort to corrupt the men or to slip into the crews sufficient bad characters to start a mutiny. In this they had the help of the crimps -

In addition to the packets there were two other types which had an evil reputation, the “Down East Bloodboats,” which ran from the Eastern States to the North Pacific ports, and the “Bluenose Hell Ships”, which hailed from the Maritime Provinces of Canada. Both these types had an evil reputation, as their names suggest; but there is no doubt that in the Canadian ships almost invariably, and in the “Down Easters” generally, the really good seaman who did his job cheerfully and efficiently was immune from any brutality, although he was certainly sworn at thoroughly and frequently.

Some officers were, of course, naturally brutal, and there are a number of undeniable instances of deliberate torture; but brutal officers were in the minority. The root of the trouble lay in the fact that most officers regarded the seaman as thoroughly bad, born lazy and always ready to take advantage of the least weakness, and that it was their duty to the owners to treat him in the same manner as slave-

They regarded the hardest possible work as the best policy for checking grumbling and dissatisfaction among the forecastle crowd. With this idea in view they found any number of unnecessary tasks, especially during the men’s watch below, when they had the right to rest. Brass yard-

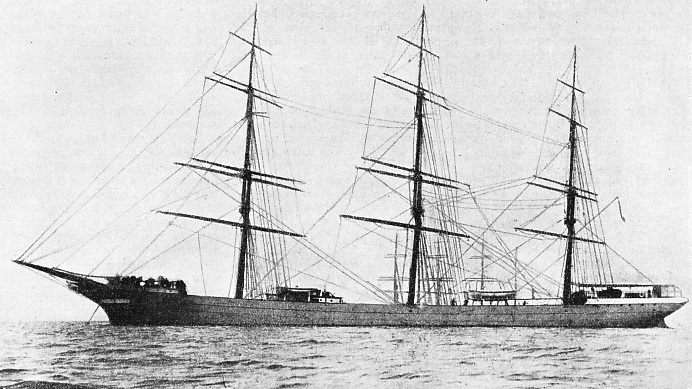

NO RECORD OF BRUTALITY was associated with the Antiope, but she had such an extraordinary reputation as a man-

It was entirely through a mistaken idea of the owner’s interests, and seldom to help themselves, that the officers would deliberately “haze” a crew, “work the very soul-

These men wanted to be well paid, it is true, but their pay came out of their advance notes, so that the owner was seldom out of pocket. The policy was calculated to guard against the danger of idle hands in port getting into mischief, as well as to save money for the owners. But, with men who were sufficiently far-

Another instance of brutal treatment forced on the officers by the supposed interest of the owners was in the shipping of seamen who were willing to take a berth at far below the normal rate of pay. Such crews generally consisted entirely of foreigners, with a large proportion of gaol-

A terrible example of the result of such a policy is that of the British ship Lennie in 1875, which, to save her owner’s money, shipped a crew which were the sweepings of Antwerp. The crew included four Greeks, three Turks, one Austrian, one Dane and one alleged Englishman, with a Belgian and a Dutch boy in the steward’s department. The British officers treated this crowd with consideration and strict justice, but they mutinied and every man in the afterguard was murdered, only the gallantry of the Belgian steward and the Dutch boy bringing the mutineers to justice. Within a year or so the public was shocked by the similar instance of the British ship Caswell. But Captain Best of the Caswell was undoubtedly a brute, and he did his best to drive his crew to mutiny, although there is every evidence that mutiny had been intended from the beginning.

The American sailing ship captains of the better type always made a particular point of leaving manhandling to their mates, although many of them had the reputation of having done it efficiently enough in their young days. British masters were more inclined to take action themselves. The title “bully”, borne by many American and British captains, was not always intended as an epithet, although it often was. “Bully” Waterman once shot a wretched seaman who was helpless with frostbitten feet. “Bully” Hayes was a scoundrel who mixed slaving with murder and was himself murdered; but “Bully” Pattman, “Bully” Martin and many others were just “hard cases” under whom real seamen were proud to have served and about whom they told dog-

The mates were generally worse than the masters. Perhaps the worst type of “bucko mate” was the man disappointed of his command through a reputation for unreliability because of drink. There were many of them in the old sailing ship days, often fine seamen, although they generally went to pieces in the end. The wise seaman kept clear of any ship in which they were sailing. Every sailing ship, no matter how peaceful and well run, carried, as a natural precaution, sufficient firearms for her officers at least.

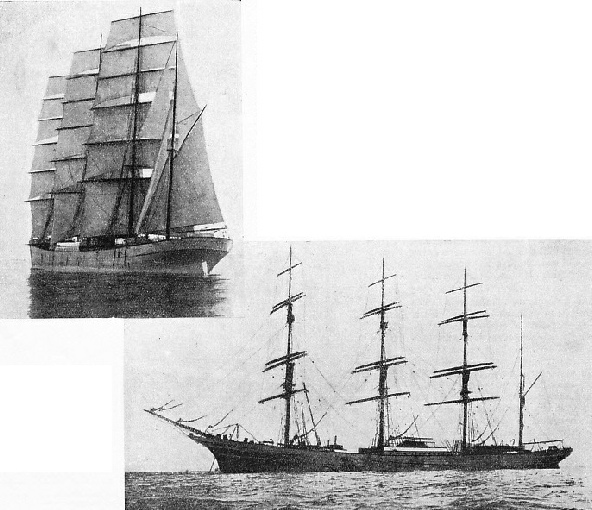

UNDER SAIL AND AT ANCHOR.

Two photographs of the James Kerr, a ship the memory of which is revered for the sake of Captain Powles, enthusiastic musician and sportsman, whose early influence was felt by many of his apprentices throughout their lives.

But the American “bucko mate”, having to deal with a rough forecastle crowd, invariably went on watch with knuckle-

Perhaps the most brutal weapon of all, undeniably used in some ships, was a 3-

For one thing, they knew they had little chance of success. If the complaint were lodged at a port of call in the middle of a voyage it generally had to go before the British Consul. He was almost invariably a local business man dependent on the ship and her owners for his living, so that he was unlikely to give judgment in favour of the men. If their complaint was dismissed they could be assured of a terrible time for the rest of the voyage. If they waited until the voyage was over, when they could no longer be penalized, they generally forgot all about their grievances after the first few hours of unlimited liquor on their pay day. Occasionally they would take justice into their own hands and the captain or mate would find himself in the dock one dark night; but as a general rule the men forgot.

Bribing the Jury

If it appeared obvious that the case would come before a court, the captain or officer concerned could generally arrange his escape by tug before the men could get ashore to lodge their complaint. This was often done with the connivance of the Customs and the police, and it certainly saved many a condemnation for murder or manslaughter. If the case did come before the courts it was often easy enough to buy a packed jury. If that failed, a financial arrangement with the local crimps would ensure that all the hostile sailor witnesses were shanghaied and shipped off for a long voyage, when the case would be dismissed for lack of evidence. But there were many instances of bullies receiving their deserts, even in the United States, where the officers were popularly supposed to have it all their own way. The “Down Easter” Gatherer, a ship with an evil reputation, had two suicides in one voyage, which was too much even for San Franciscan opinion in the ‘seventies. One Scandinavian went mad because of the cruelty of the mate and dived off the royal yard, and an American cut his throat on the taffrail and jumped overboard afterwards. One seaman was shot dead by the mate on the same voyage. Finally, Captain Sparks was hounded out of his command, and his mate Watts received a sharp term of imprisonment.

The “Floating Homes” were not nearly so conspicuous as the “Hell Ships” -

THE BRENDA was a floating home under Captain “Jamie” Learmont, who always had his wife on board and took the greatest care to teach his apprentices all that he possibly could -

Many captains and many owners attempted to make their ships comfortable and happy for the men and boys who were serving in them, but they were not always successful. The classic instance is that of the Inchgreen, built in 1877, for which the owners provided a deckhouse forecastle with two-

For one thing, of course, with a conservative mind such as that of a seaman it is necessary to make such reforms gradually. It was firmly implanted in the heads of the men that there was no kindness about the matter; that these reforms were made merely to secure the small reduction in the rates of pay. But there is no doubt that plain features which were introduced into ship design without such advertisement, for the purpose of securing greater comfort, were appreciated at once. But it was the personal side that counted for infinitely more in making a happy ship than any material considerations that could be planned by the owners. All the officers contributed, but the greatest influence was that of the captain and, if she were carried, as she was so often in the sailing ship, the captain’s wife.

Unfortunately, it was only one woman in a dozen who was successful; if she interfered in the working of the ship, or overshadowed her husband, the vessel became what was known as a “hen frigate”, and there was nothing which the sailor hated as much. There are many instances of such a vessel coming to grief for no other reason than that the captain’s wife was interfering in her management, or that she had put all hands so much on edge that they became demoralized.

But when she happened to be a real seawoman, possessing tact and kindness in equal measure, she was offered a whole-

Every ship that Powles commanded was a happy one; he was a musician to his finger-

In another “floating home”, the Brenda, and later in the Bengairn, Captain “Jamie” Learmont and his wife were real parents to the apprentices. He insisted on discipline, and one of his little fads was that no half-

In another “floating home”, the Brenda, and later in the Bengairn, Captain “Jamie” Learmont and his wife were real parents to the apprentices. He insisted on discipline, and one of his little fads was that no half-

THE BEAUTIFUL CIMBA was so popular that seamen would accept casual labour in the docks, so that they could be at hand when Captain Holmes was signing on his crew.

Mrs. Brown, who generally sailed with her husband when he was master of the North Star, worked on the principle that it was best to make the ship resemble the good homes from which the apprentices came as far as was possible in a sailing ship.

Captain Tod, the popular master of the Shakespeare, had a wife who was loved by everybody, and the presence of two sunny-

The numerous apprentices who served their time in the Shakespeare always remember the manner in which they were kept clear of the temptations which generally beset a youngster in port. There was no preaching or strict regulation, but the captain and his wife kept “open ship” for apprentices of all the other ships in harbour. The birthday of an apprentice oil board was never forgotten and -

You can read more on “In the Sailing Ship’s Forecastle”, “Life in the East Indiamen” and

“Romance of the Racing Clippers” on this website.