© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The North Atlantic Ice Peril

In the North Atlantic Ocean the International Ice Patrol keeps a vigilant look-

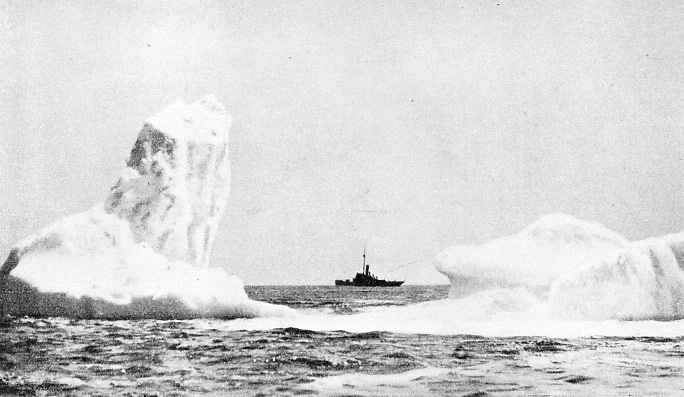

IN ONE YEAR THE INTERNATIONAL ICE PATROL sighted no fewer than 1,351 icebergs. This patrol, under American command, was begun in January 1914, a sequel to the 1913 International Conference on the Safety of Life at Sea. The necessity for such a patrol was realized after the Titanic disaster, April 1912. The iceberg danger to transatlantic shipping is greatest in the neighbourhood of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland.

DURING the period of more than twenty years since the International Ice Patrol has been established, not one life has been lost through a ship colliding with an iceberg in the North Atlantic. This creditable record is mainly due to the work of the patrol in locating bergs and sending news of them by wireless to all ships; it is due also to the efficient look-

Icebergs are among the most dreaded dangers to navigation, particularly in the North Atlantic Ocean, because at certain seasons of the year they float south athwart the shipping lanes. The Labrador Current brings the bergs down from the Arctic. In the days of sail most vessels on the run between Europe and North American ports were too far south to be in danger; but the steamship routes were more direct, and ships were lost by striking icebergs.

The worst disaster on record was the loss of the White Star liner Titanic on her maiden voyage on the night of April 14-

The iceberg danger is perhaps greatest in the vicinity of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. Great bergs, sometimes several miles in length, become detached from the Arctic ice-

If the mass above water is high and white the danger is not so great. In daylight and clear weather the berg will be seen for a fair distance and avoided; in fog the cold mass will chill the air and warn the experienced mariner; and in rough weather the sea will break round it and give audible as well as visible warning. Some mariners claim to be able to smell icebergs -

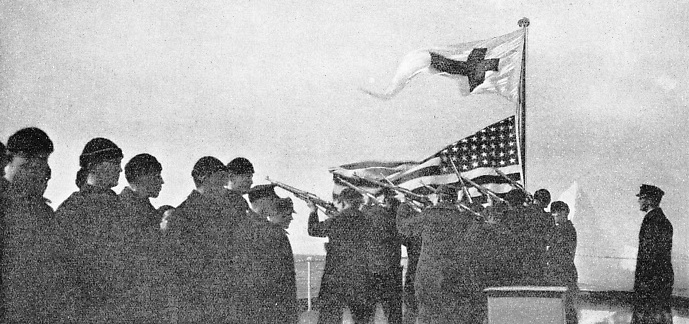

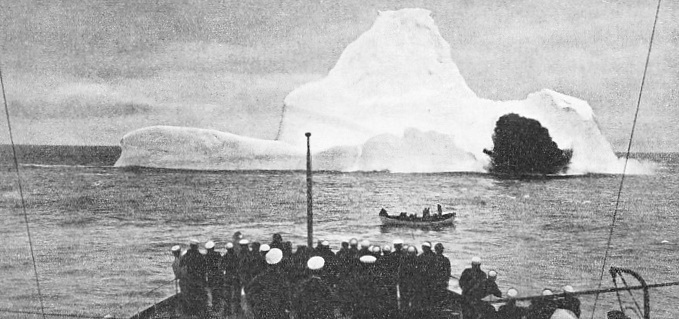

IN MEMORIAM. Members of the crew of an International Ice Patrol coast-

On several occasions ships or the crews of shipwrecked vessels have anchored to icebergs or have taken refuge on them and so drifted to safety. On May 8, 1854, the Resolute, one of the vessels of Sir Edward Belcher’s expedition in search of traces of the Franklin expedition, was abandoned in Barrow Straits, north-

The Fox, in which Captain M’Clintock reached the spot where the Franklin records were buried, was frozen into the pack ice from August, 1867, to April, 1868, after which she drifted 1,385 miles in 242 days. The exploration ship Polaris, which set out from Connecticut to explore the north-

Because of their size icebergs often reach currents below the surface of the sea which are counter to the surface currents. In fact, one explorer, Dr. Kane, took advantage of this fact by anchoring his ship to an iceberg, and thus was pulled north against the wind and the surface current.

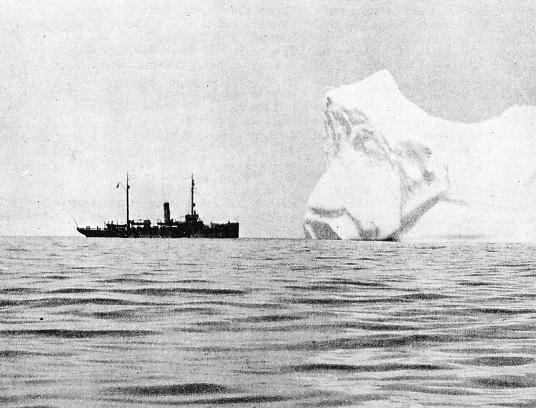

DURING SPRING AND EARLY SUMMER the ice menace in the North Atlantic is at its greatest. The International Patrol keeps in daily touch with the bergs, determines their set and drift, reports to the U.S. Hydrographic Office and broadcasts to ships. The patrol also gives any assistance required by ships and carries out scientific observations.

Green and blue colours are often seen in the icebergs of the North Atlantic. The bergs which break away from the glaciers carry earth and stones which they later deposit into the Atlantic.

In the ’nineties Fridtjof Nansen, the Norwegian explorer, proved that the Arctic ice-

This question of keeping ships out of the track of danger on the routes from Europe to the United States was first considered by Lieutenant F. M. Maury, of the United States Navy, who was a navigational genius. To lessen the danger of collision, he suggested, in 1855, that ships eastbound should follow routes different from those taken by westbound vessels. His suggestion was not adopted for twenty years, the first company to lay down specified routes being the Cunard. This was the real beginning of the shipping lanes, and various alterations and improvements followed. Seasonal tracks were established which varied according to the month and the condition of the ice. But the Titanic disaster showed that this safeguard was not adequate in abnormal conditions.

After the loss of the Titanic, the United States Government and the British Board of Trade took steps to deal with the peril. Two U.S. Navy scout cruisers patrolled the ice regions in the danger months of 1912, and in the 1913 season the work was performed by the two U.S. Coast Guard cutters Seneca and Miami. The British Government called a conference of various shipping companies early in 1913, after which the auxiliary whaler Scotia, which was then over half a century old and known as a reliable little ship, was chartered and fitted out for the service. The cost was divided between the Board of Trade and the British shipping companies operating transatlantic services. The Scotia’s work was confined to ice and weather observations off the Newfoundland coast; and, although she was hampered by fog and storm, she rendered good service. She cooperated with the two U.S. cutters in sending information to ships.

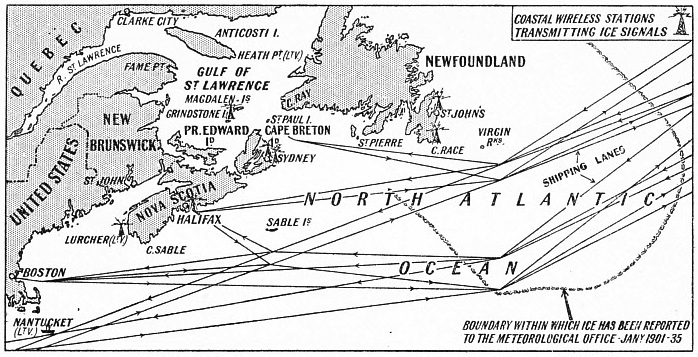

THE WIDE REGION guarded by the International Ice Patrol is shown on the this map. Vessels of the patrol guard the south-

The main duty of the officers of the cutters was to locate bergs and warn passing ships. In addition they had to study the ice problem, particularly in connexion with the currents near the Grand Banks; the properties of the ice, its drift, erosion and melting; the temperatures of the sea and air near the ice; and the habits of birds and seals in relation to ice. They were further expected to gain all information which could be of aid to mariners.

Towards the end of 1913 an International Conference on the Safety of Life at Sea met in London, and the present International Ice Patrol came into being, as a result, in January, 1914. This has been in operation ever since, except for the years 1917 and 1918 when the United States were at war.

The primary duties of the patrol are derelict destruction, ice observation and ice patrol service. At first the service, consisted of two vessels which patrolled the ice regions in the danger season and tried to keep the shipping lanes clear of derelicts during the rest of the year. The management of the service was undertaken by the United States Coast Guard Service.

Work began in 1914, and a later convention in 1929 defined the present arrangement. Fourteen countries contribute to the cost, the British contributing 40 per cent, the United States 18 per cent, Germany 10 per cent, and other nations smaller proportions according to their quota of Atlantic traffic.

The vessels take all possible steps to destroy or remove derelicts found east of a line drawn from Cape Sable (Nova Scotia) to a point in latitude 34° N., longitude 70° W. Up to three vessels are provided. In the ice season they guard the south-

In the spring and early summer the iceberg menace is at its greatest, and the patrol keeps in daily touch with the bergs and field-

The cutter Seneca made a name for herself as a kind of super-

Conditions vary from year to year. Generally the patrol vessels work in hazardous conditions. In the 1931-

Three oceanographic cruises were made during the season, and three current charts were drawn of the ice regions, these charts being used by the cutters to determine the probable set and drift of the bergs. The observed drifts coincided with the reputed currents.

In the following year the U.S. Coast Guard vessel General Greene was sent, up first to locate the icefields and icebergs; her call letters were notified to all vessels in the North Atlantic, and these were asked to report to her any icebergs sighted. When the ice drifted south and made constant patrol necessary the cutters Champlain and Mendota began the patrol alternately.

In 1934 the cutters General Greene, Pontchartrain and Mendota performed the service, the General Greene opening the service, sailing from Boston on April 2. On April 24 the Cunard White Star mail liner Georgic sighted twenty bergs and numerous growlers; (small icebergs) while crossing the Grand Banks from west to east. On June 12, in Davis Strait, between Baffin Island and Greenland, a berg seven miles long was reported in latitude 62° 53' N., longitude 60° 45' W. This huge mass ol ice bordered an icefield which extended as far as could be seen. The Ice Patrol sighted about 600 bergs near the Grand Banks in the 1934 season. The record, however, up to the time ol writing is 1,351 icebergs seen in 1929.

Three shipping tracks, revised in March, 1931 have been established between Europe and the United States, and four between Europe and Canada They are used by the ships concerned according to the season of the year.

BLOWING UP A BERG. The crew of an Ice Patrol cutter watches the effect of high explosives on a floating mountain of ice. Although the work of the Patrol began in 1913, a later convention in 1929 defined the present arrangement under which the management of the service is undertaken by the U.S. Government. Fourteen nations, including Great Britain, contribute to the cost.

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this article.

You can read more on “Adventures of the Ice-

“The Franklin Mystery” on this website.