© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Manchester Ship Canal

The city of Manchester is nearly forty miles from the sea, but the enterprise of building the great waterway known as the Manchester Ship canal has made this city one of the leading commercial ports in Great Britain

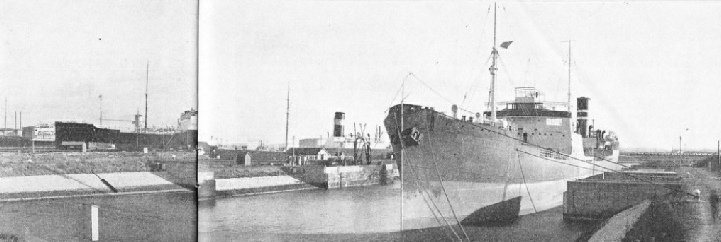

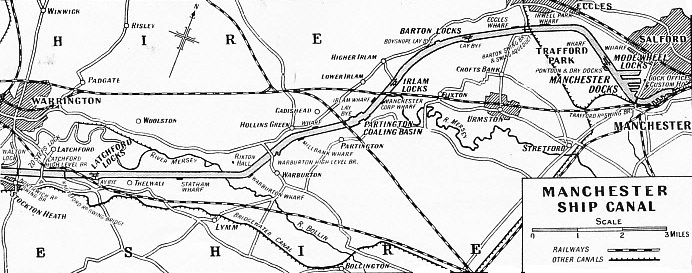

THE GATEWAY TO MANCHESTER. On the south bank of the River Mersey, at Eastham, six miles above Liverpool, are situated the entrance locks to the Manchester Ship Canal. These locks are tidal, and vessels up to 15,000 tons deadweight capacity regularly use the canal. The canal is 120 feet wide at the bottom, and the depth at the entrance is 30 feet.

SINCE the construction of the unique artificial waterway known as the Manchester Ship Canal, the inland city of Manchester has become one of the busiest ports of the United Kingdom. The Ship Canal, over thirty-

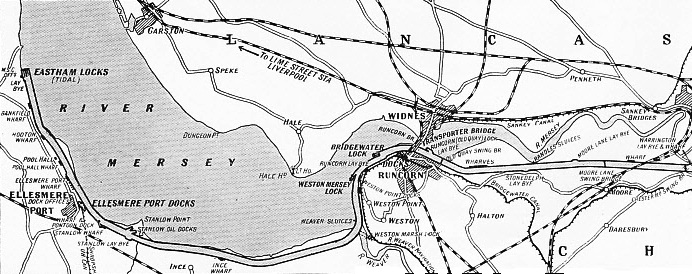

The entrance to the Ship Canal is on the south side of the River Mersey at Eastham, six miles above Liverpool and nineteen miles from the Bar Lightship. The whole canal -

A traveller on the railway from Lime Street, Liverpool, to Crewe and London passes over a high viaduct shortly after his departure from Liverpool. This viaduct spans the River Mersey and the Manchester Ship Canal at Runcorn.

The docks at Runcorn cover an area of seventy-

The Bridgewater Canal, forty-

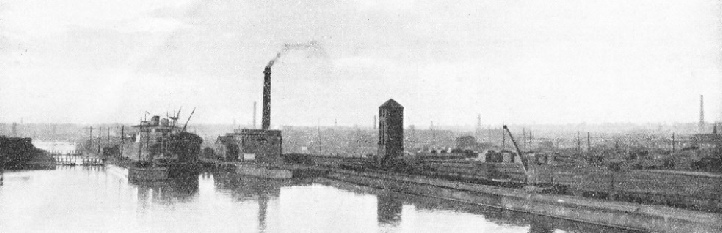

THE MODE WHEEL LOCKS bring the Ship Canal to its total height of 70 feet above mean sea-

The Bridgewater Canal junction with the Ship Canal at Runcorn provides a connexion with the canal system of the Midlands. The Weaver Navigation joins the Ship Canal at almost the same point. At Ellesmere Port the Shropshire Union Canal affords another route from the Port of Manchester to the Birmingham area. The Manchester Ship Canal Company provides eighteen 40-

The lowest twelve miles of the Ship Canal were largely regained from the Mersey by building embankments. A further twelve miles were cut through the land. The next four miles were made by canalizing the Mersey up to its junction with the River Irwell. This river forms the upper section and completes the waterway to Manchester Docks.

Five locking systems raise the canal 58 ft 6-

The Ship Canal encloses several small harbours and docks that were originally accessible from the Mersey, notably at Runcorn and Ellesmere Port. Where Parliament has required it, locks have been provided to allow for a direct route into the river from these harbours.

The canal is regularly navigated by ships of 15,000 tons deadweight, and its width at bottom is 120 feet, widening at certain points. The excavated depth up to Stanlow is 30 feet and from there to Manchester 28 feet. The canal is crossed by several swing bridges, by one barge canal (the Bridgewater Canal), and by seven fixed bridges. The lowest fixed bridge allows a clear headway of 73 ft 6-

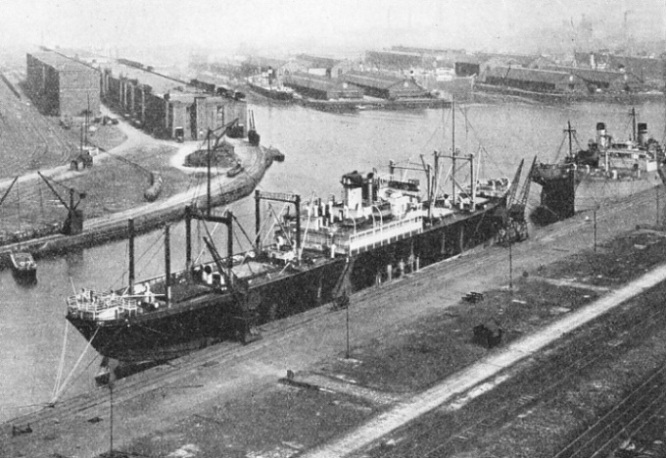

OIL TANKERS AT STANLOW, near the entrance to the Manchester Ship Canal, where there are 145 storage tanks with a capacity of 82,000,000 gallons. The storage and refining plant is all on the south side of the canal, and tankers discharge in the docks on the opposite side. On the right of this photograph is the tanker British Freedom, 6,985 tons gross, in No. 2 Oil Dock. She has a length of 440 ft 1-

Manchester as a world port was the dream of Lancashire folk for many years. The possibility of making a navigable waterway from the estuary of the River Dee was discussed more than a hundred years ago. For sixty years the idea seems to have been set aside, to be revived again in 1877 when the Manchester Chamber of Commerce, perturbed by the decline of business in the city, expressed the opinion that a waterway capable of bringing large vessels up to Manchester was required to restore its fortunes.

Daniel Adamson took the first practical step by calling a meeting of local authorities and leading industrialists to discuss effective measures for driving a deep waterway from the city to the sea. This historic meeting took place in June 1882, and the proposal considered was this time a waterway to connect with the Mersey. Two schemes were reviewed; one for a tidal waterway, the other for a canal with locks. The former scheme was rejected, as it would have entailed a dock system lying 60 feet below land level. It was wisely thought better to raise the incoming merchandise in the ships themselves rather than submit to the handicaps the other scheme would have involved.

Then ensued a long fight for Parliamentary powers to proceed and the plans underwent many modifications. The Royal Assent to a third and final Bill was given on August 6, 1885. The contract was placed in June 1887, and the first sod was cut at Eastham in November of the same year. The construction provided employment for thousands of men. The canal was eventually finished after six years, at a capital cost of about £15,000,000. It was opened for traffic to Manchester on January 1, 1894. The formal opening by Queen Victoria took place nearly five months later on May 21. Seventy-

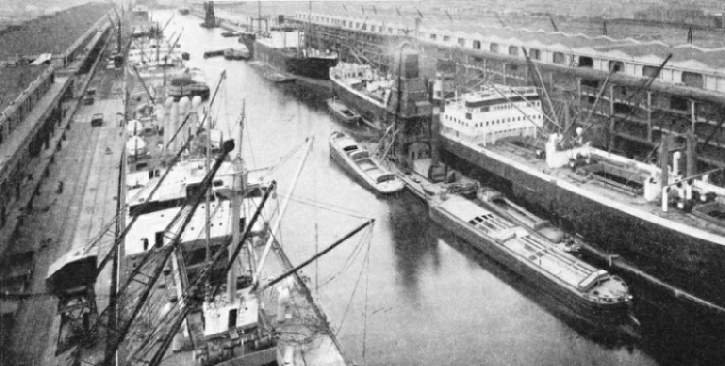

ALONGSIDE TRAFFORD WHARF in the dock system at Manchester lie the Manchester Regiment, 5,989 tons gross, in the foreground, and next to her the Cyprian Prince, 3,071 tons gross.

The record of the port has been one of success from the time of its opening. The annual tonnage has risen from under a million to nearly seven millions. The port’s equipment and facilities have outstripped expectations, and its connexions have extended; yet it is still, in the opinion of its own citizens, quite young and possessed of the will and the power for greater development.

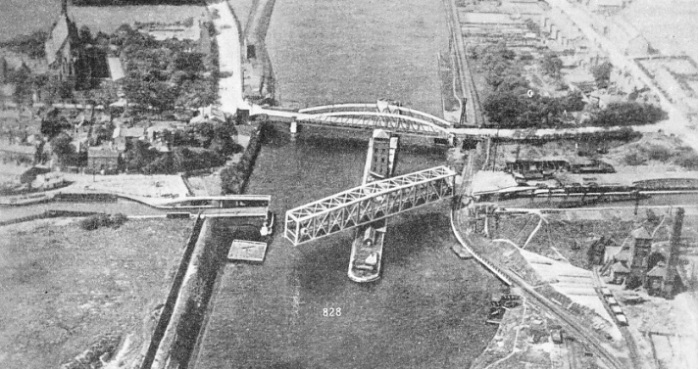

The building of the Ship Canal introduced many difficult engineering problems. The Bridgewater Canal, for instance, had to be carried over the Ship Canal on a swing aqueduct. The present steel aqueduct, which opens to allow the passage of vessels up and down the Ship Canal, replaced the stone aqueduct designed originally by James Brindley. The new aqueduct was necessary because of the size and height of ships using the Ship Canal.

The original stone aqueduct was fixed. The Bridgewater Canal, if it was to continue to span the new waterway, had to be carried across on a swing bridge. The present aqueduct is a swing bridge revolving on a central pier. It is built in the form of a trough. To avoid the delays that would occur on either waterway by the emptying and refilling of the trough every time the bridge was opened, it is swung when full of water. This is achieved by closing, with a system of gates, the ends of the trough and the abutting ends of the Bridgewater Canal. When the bridge is to be opened, these gates are closed and the swinging section with its trough of water moves into a position in line with the Ship Canal. When it is swung back across the Ship Canal again, the gates are opened and the trough becomes once more a continuous section of the Bridgewater Canal.

To keep the aqueduct water-

NEARLY THIRTY-

The aqueduct is 235 feet long, 23 ft 9-

The dock equipment includes 52 hydraulic, 44 steam, and 126 electric jib cranes, with a radius of from 16 feet to 40 feet. Further facilities are provided by electric overhead travelling cranes, 36 electric hoists, a floating crane with a lifting capacity of 60 tons, and a pontoon-

As an oil port, Manchester is second only to London in Great Britain. Manchester’s oil traffic dates from the opening of the Ship Canal in 1894. In the early years,consignments came solely in casks, but in 1897 tanks were installed and the new technique in oil-

The next step in the development of Manchester as an oil port was the provision of facilities for petroleum spirit and low flash-

THE PORT OF MANCHESTER is regularly used by freighters on American services. On the right of this photograph is the Pacific Exporter, a twin-

After the opening of this dock in July 1922 traffic increased until it became necessary to add a second dock. No. 2 Dock, larger than its predecessor, was opened in May 1933. This dock is 650 feet long and 180 feet wide and has berths for two large vessels. Either dock has a depth of thirty feet of water. The building of No. 2 Dock more than trebled the importing capacity at Stanlow, where all volatile oils, flashing at 73 degrees Fahrenheit or less, are discharged. The tanks at Stanlow have a capacity of more than 82,000,000 gallons. The tanks at all points on the canal number 352 and have a total storage capacity of more than 138,000,000 gallons. The storage and refining plant is all on the south side of the canal. The docks in which the tankers discharge at Stanlow are on the opposite side of the waterway. This is one of the many safety precautions adopted by the Ship Canal Company.

To permit easy access, the oil docks lie at an angle to the line of the canal. Ships can be swung in the entrance basin. When a vessel has entered one of the docks the entrance is closed by a floating boom.

For cereal cargoes there are two grain elevators at Manchester Docks, either having a storage capacity of 1,500,000 bushels. Conveyer bands beneath the quays enable several ships to discharge bulk grain simultaneously. Floating elevators ranging in capacity up to 250 tons an hour are also provided.

The staple industry of Lancashire at the beginning of the century was the cotton trade. This trade was largely responsible for the enterprise which led to the building of the Manchester Ship Canal. Manchester is now reaping, in other directions, the profits of her initial enterprise. Although the city is nearly forty miles from the sea, the great Ship Canal has made Manchester a destination for shipping of almost every type and nationality.

ONE CANAL CROSSES ANOTHER. A unique aqueduct carries the Bridgewater Canal across the Manchester Ship Canal between Barton and Manchester. The aqueduct is built in the form of a swing bridge to allow ocean-

You can read more on “Britain's Canal System”, “The Caledonian Canal” and “The Kiel Canal” on this website.

You can read more on “Britain’s Biggest Ship Canal: The Manchester Ship Canal” in Wonders of World Engineering