© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Handling the Overseas Mail

The carriage of letters and parcel post to outlying parts of the world is one of the most important services rendered by shipping. The organization of the overseas postal services is remarkable for its complexity and its efficiency

Loading the Continental mail at Dover. The shortest mail route from Great Britain to the Continent is from Dover to Calais. This photograph shows mail-

MANY of us, during the course of the year, send letters or parcels to Egypt, East Africa, India, the Straits Settlements, China, Japan or Australia; but, apart from the writing and posting of the letter or the packing and posting of the parcel, we have little further concern. The subsequent travel of this letter or parcel, however, is of great interest.

Our newspaper tells us which ship will take our mail to the countries mentioned above. This vessel may at the moment be lying alongside in Tilbury Docks, Essex, or in King George V Dock, London, where she is merely discharging or loading cargo and perhaps a certain amount of passenger baggage.

Before her arrival in London, however, the mail officer has prepared an estimate of the space he will require for the mails and parcels for the ensuing voyage. He will also have prepared a stowage plan – a plan of the compartments in the ship where the mails or parcels for each separate port of call and country are to be stowed.

These space and stowage plans will have been approved by the commander of the vessel, and copies will have been sent to the personnel in charge of the loading of mails on the quayside and to the clerk who acts as liaison officer between the General Post Office and the ship. This greatly simplifies the work and leads to a lessening of congestion on the quayside. For the General Post Office can then not only label its vans with the port for which the mail is consigned, but can also place on the van the number of the hatch or hatches in which that particular mail is to be stowed. The shunters on the railway line can, therefore, bring their mail vans alongside the correct dace and so organize and effect a quick and orderly stowage.

The mail ship leaves London on Fridays for her voyage to Bombay, the Far East or Australia. On the previous Monday the first consignment of parcel post comes alongside, followed by other consignments right up to the time of the vessel’s departure.

An Australian mail ship will probably load parcel post for the following destinations: Gibraltar and Tangier, Egypt, Aden and East Africa, Bombay, Karachi and the Persian Gulf, Colombo, Federated Malay States, China and Japan. As many as 1,500 “parcels” are normally addressed to the Indian ports, and perhaps only 100 to Gibraltar and Tangier. About 1,000 parcels are generally consigned to the Australian ports, Fremantle, Adelaide, Melbourne. Sydney and Brisbane.

Parcels for each of these various destinations must be loaded into a separate compartment or corner of a compartment. To ensure that the correct parcels are going into their appropriate places, a careful check is made on the quay and also by one of the ship’s staff on board. Parcel post stows at approximately seven bags to the ton space of 40 cubic feet. The total number of parcels that make up an average mail will take up some 450 tons space.

An hour or two before sailing, the mail for Gibraltar, Tangier and the coast of Morocco arrives with the final parcel post. Included in this will probably be the confidential mail for the authorities in Gibraltar. These mailbags must be stowed in a particular position, perhaps in the bullion-

During this time the ordinary first and second-

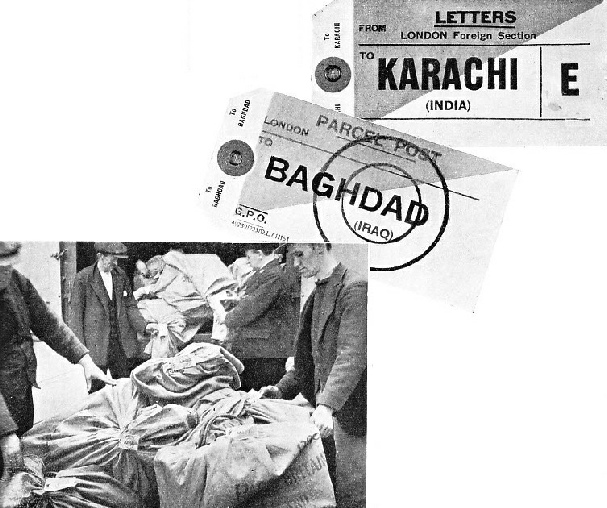

In the main towns of Great Britain the mail for foreign countries is collected. At certain times, as shown on the boards outside any post office, the mail is closed and the bags proceed by rail to Dover. At Dover the mails from every town and the vast London mail are gathered together, checked and sorted by the Post Office officials. Every bag is carefully examined, and a detailed tally is taken of the numbers, where they come from and where they are to go. This information is entered on what is called a Way Bill, and there may be more than 10,000 bags of mail to be checked and entered. The Christmas mail may bring as many as 15,000 bags. The first consignment of the mail is sent across to France and arrives at Marseilles alongside the ship about 11am on the Friday morning, and the final mail train arrives about 11pm that same night. In this train travels the courier from the GPO, who has in his care official Government mailbags for the various Governments, Government Departments and Ambassadors of the countries concerned.

Stowage Problems

Before the arrival at Marseilles of the mail alongside the ship, the mail officer on board has been busy. Already he will have drawn up his stowage plan and arranged the details as to where the mail for each particular destination is to be stowed. The loading of the mail occupies a certain amount of time on the Friday afternoon, and begins again at 9pm on the Friday night. It is finished usually between 4 and 6 o’clock in the morning. If, because of fog or any other contingency, the final mail train is late, then loading may not be finished until well on into the following Saturday forenoon.

The main thought in the mind of the mail officer is to expedite the stowage of the mail and to do this in the most simple and speedy manner. He allows thirteen mail-

In the mail train which arrives about 11pm it is usual to find the Indian mail in the forward part and the Australian mail aft. Stowage in the ship is arranged accordingly to minimize confusion at the quay by avoiding crossing streams of carriers. The train is on the far side of the shed, some 80 feet or more from the ship’s side. The authorities on the quay are given a stowage plan and carriers take the mail-

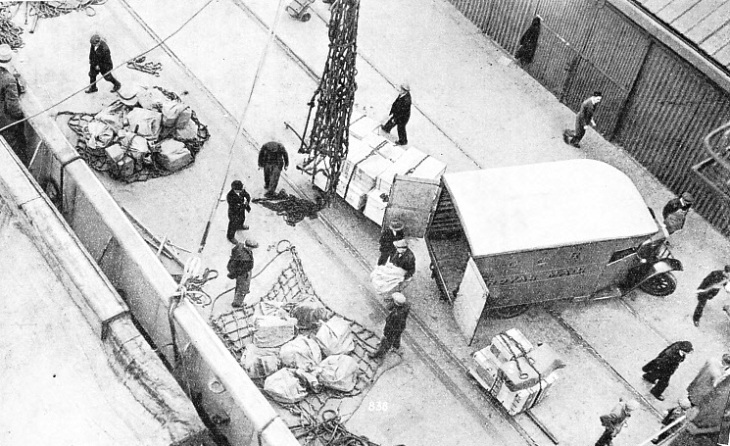

Parcels for the Far East are loaded into P & O liners directly from Royal Mail vans on the quays of Tilbury Docks, Essex, or of King George V Dock, London. A P & O liner sails every Friday, but the bags are loaded every day from the previous Monday. An average parcels mail consists of about 2,500 parcels every week. The bags are all carefully checked and their position in the ship’s holds is plotted beforehand on the stowage plans.

From these dumps other carriers carry the bags one at a time. They pass by two of the ship’s personnel, of whom one examines the label while the other gives the carrier a stick. The carrier then throws the bag into the mail nets directly against the ship’s side. The stick is given to another member of the ship’s staff, who places it in a sectioned box. Each box contains 100 sections, so that a careful running tally is taken of the number of bags going to each individual port.

As soon as there are enough bags in the net sling, say sixty or seventy, the sling is hoisted, on board and lowered into the hatch-

This operation goes on throughout the year in fair or foul weather. It is not a pleasant task, with the cold northwest wind known as the mistral blowing, or with the rain beating down, to stand on the quayside and check this constant stream of mail-

It is not uncommon for a man sometimes to pick up two mail-

When all the mail has been stowed away, a diligent search is made by the officers and officials throughout the railway train and the quayside to make quite sure that no small bag or bags have been hidden or misplaced among the piles of merchandise lying in the open shed.

The officer who is in charge of the loading of each hatch brings with him his tally of the number of mail-

Despite the careful scrutiny of every mail-

The destination of mail-

When dealing with the Australian mail an additional division must be made between the first-

This task of “turning over” may take two or more days, but on completion the mail officer is sure that no bag can be carried beyond its destination. At every port of discharge the mail must be checked and must agree with the figures taken either from the Way Bill or from the mail officer’s tally. A receipt must be obtained from the shore postal authorities. This applies also to the parcel post.

The first port of call after Marseilles is probably Malta and the next Port Said. Here there is a certain amount of mail to go by the overland motor route to Haifa and Baghdad, At Aden the East African mail is discharged. This is transferred to another ship, to be landed at various ports down the coast. The morning before arrival at Bombay the Indian mail must be sorted and stacked in its various groups to facilitate discharge into the post office alongside Ballard Pier, Bombay, or directly into the waiting trains. The Federated Malay States mail will also probably be discharged at Bombay and will go by the way of Madras to Penang and other destinations. The ship arrives alongside Ballard Pier about 5pm. By 10pm the whole of the mail and parcel post will normally have been landed and stowed away into the mail trains for Calcutta, the Punjab or Madras and the local mail delivered. The mail ship then proceeds to Colombo, Ceylon, where the China and Japan mail is landed, with the local Ceylon mail-

The simple act of dropping a letter into a pillar-

This description of the mail services to the East applies to almost all overseas mail routes, although in every route there are individual differences. In some parts, for instance, specially-

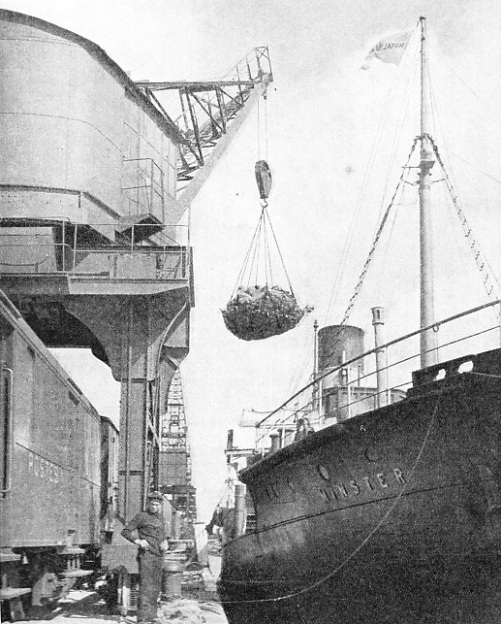

The proximity of Great Britain to the continent of Europe entails the transit of an enormous quantity of mail across the English Channel. There is a number of routes in regular use. The shorter cross-

Harwich is another main port for the dispatch of Continental mails. Routes radiate from there to Flushing, Hook of Holland, Antwerp and Esbjerg, Denmark. The Scandinavian mail goes from Newcastle-

Contracts for the carriage of overseas mails provide important business for many shipping companies. Occasionally the contracts change hands, but not often. The mails for India, Australia and the Far East are carried under contract by the P & O Company. Orient liners also carry mail to Australia. Cunard White Star liners carry the mails to the United States, and Canadian Pacific liners to Canada. The South African mail contract is held by the Union Castle Line and the West African by the Elder Dempster Line.

In addition, mails are carried by other companies. sometimes mails reach their destination by different routes. In 1936 the Egyptian mail, for instance, left London on Mondays for the Piraeus, Greece, by land. There it was taken over by a Turkish or Romanian packet. A P & O liner picks up the Thursday mail at Marseilles, and the following day an Italian ship takes over the British mail from Naples or Brindisi. Saturday’s mail may cross to Egypt from Naples in an American ship.

To obtain the most efficient postal services it is necessary to use the fastest vessels available.

obtain the most efficient postal services it is necessary to use the fastest vessels available.

A French mail train waits alongside the quay at Calais for the British mails from Dover. The vessel in this photograph is the Minster, flying the Royal Mail pendant at her masthead. She is a twin-

You can read more on “The Canterbury”, “Filling the Ship” and “Ships in Postage Stamps” on this website.