© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Romantic Sailing Coasters

Until recently, one of the commonest types of craft to be seen round British shores was the sailing coaster, which has played an important part in the development of merchant ships

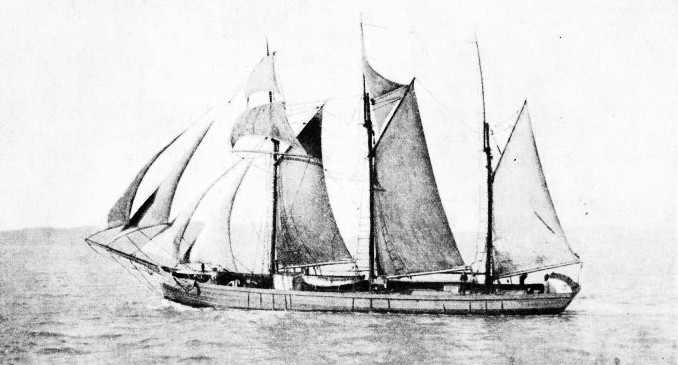

THE COASTING VESSEL BROOKLANDS. This three-

FINE as the tall ships were, and fascinating as is their story, the little matter-

Numbers of little sailing vessels of different types and sizes were grouped under the title “coaster”, but it must not be thought that they kept to the coast. The Continent between the mouth of the River Elbe, on the North German coast, and the island of Ushant, off the coast of Brittany, was regarded as being within coastal limits. When they ventured outside these limits, which they did regularly, they were supposed to have a certificated officer on board. Often they did, but it was generally a man who had been given a “certificate of servitude” when the Board of Trade tickets were introduced. Such an officer was regarded more or less as a passenger.

The coaster skippers were magnificent seamen, and seldom at a loss even when they were well outside their usual waters, so that the certificated “sailing master” was often regarded as being nothing but an encumbrance. It is to be feared that with a good charter for a foreign voyage in view, many of them would get round the regulations altogether by going to a foreign port within coasting limits and clearing thence for any destination that suited them. There was, of course, the chance of trouble when they came home again, but they were willing to take the risk.

The mainstay of the British coasting trade being the coal business, which was a seasonal one before the days of public utility companies, the coasters would employ their summer months on a number of trades. Among their most popular activities were voyages to Scandinavia to fetch ice for domestic use and for the fishing industry; they went to the Baltic for hemp and timber until they were driven out of the timber trade by the deck load regulations.

The coal trade was always the most important. In its prime, before it had been broken by railway competition and the advent of the steamer, it employed an astounding number of sailing vessels. When this trade was really established is difficult to discover. In spite of various enactments against the use of coal in London, the coal trade began to flourish at an early date, and employed a number of curious little vessels whose customs survived until recently. In the fourteenth century Tyneside coasters were taking coal across to Flanders, and the famous Dick Whittington included the coal trade in his various money-

In the early days, unfortunately, records were imperfectly kept, so that it is difficult to say just how many ships were employed; but in the nineteenth century the numbers were astonishing. During one day in December, 1837, after a spell of head winds, no fewer than 741 colliers arrived in the Thames. The veteran shipowner, Lord Runciman, who began his sea career before the mast in a collier brig, has recorded that he has known as many as 300 sail held up in Yarmouth Roads by a head wind. When a fleet of this size got under way again, it is easy to understand that the colliers wanted most of the river, and were unpopular with other ships using the port. Unfortunately the casualties among them were heavy; in twelve months of the years 1865-

Until well into the nineteenth century most of the colliers were square-

The West Country ships, which seem to have introduced the curved clipper stem into the coasting trade, were always conspicuously clean and smart on deck, with their white paint and the burnished funnels from the galley and the cabin stove. During a slack period in the West Indian trade a number of West Indiamen were chartered for the coal business. Bigger and better than

the ordinary coasters, they set an example which led to a great improvement in the design of the collier. But hard times were ahead. The railway began to carry coal to the Metropolis, the steamer could make so many extra voyages that she was always favoured in port, and a number of Scandinavian vessels entered the coal trade at cut rates when the Baltic was frozen over.

The “Rib-

The “Geordies”, as the North Country vessels were always called, thus found it difficult to keep going, and their condition rapidly deteriorated. At the same time, the necessity of economizing in crews led to the brig falling out of favour and to its replacement by the brigantine, barquentine or schooner rig. Brigantines, barquentines and schooners could be worked with smaller crews, but were not as sure of staying as the old brigs.

Many of these coasters had tiller steering, even when they were fairly large ships -

Although coasters were frequently transferred from one trade to another, the different districts had their own fashions of building. On the North-

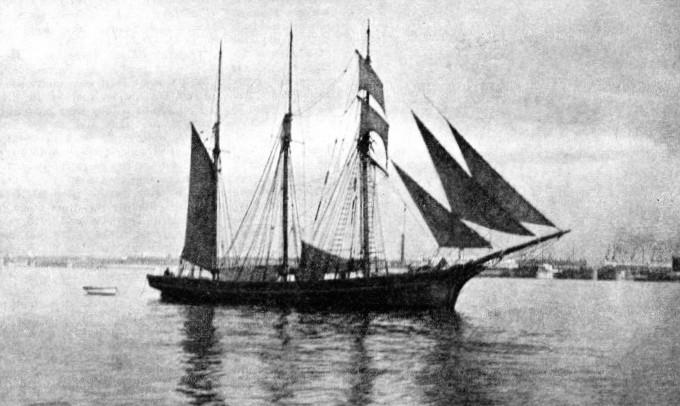

THE DUCHESS, a trim coasting vessel of 110 tons built in 1878 at Connah’s Quay, Flintshire, North Wales. She was broken up in 1935 after having run ashore near Liverpool.

In many areas the men slept in hammocks, man-

Although the great majority of these colliers were small, the bars at the entrances of many of the North-

There was a big coal trade oil the West Coast as well. Maryport (Cumberland) maintained a big fleet to deal with it. All rigs were included, but the majority were schooners. For many years the coal was always brought down to the dock in panniers slung on either side of donkeys, but eventually the coal trade was displaced by the pig-

A Water-

In addition to the coal trade, the stone trade kept a number of ships busy. It was, however, exceedingly unpopular, for it was a terribly hard cargo both on ships and on men. Broken stones or kerb stones from France or the Channel Islands provided a return cargo which was invaluable, the broken stone always being known as “Guernsey fruit”. China clay from the West Country was another useful return cargo, but it made everything dirty, was heavy for the ships and was immediately damaged by a comparatively slight leak.

Thus most of the colliers returned to the North in ballast, which cut deeply into the profits of their owners. All sorts of experiments were tried to overcome the difficulty, one of the most interesting being that in the brig Benton, in 1851. The Benton tried carrying water ballast in rubber bags, which would stow away in a small space when she was loaded with coal. These bags would keep her upright when she was empty, and when her journey was over could be started one by one and the water put over side by the pumps. In many ways the experiment was successful, but the rubber bags were expensive, and the experiment was soon abandoned.

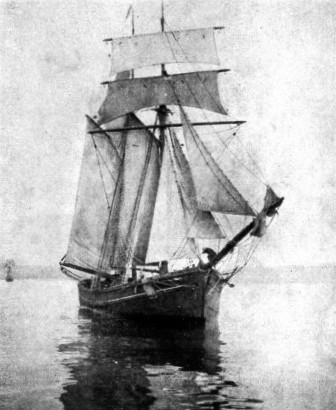

MAKING SAIL. The three-

So the colliers had to look after their safety by shipping solid ballast. Stone or sand was unsaleable, and it cost a good deal of money to remove in the Tyne, where there was an ancient horse crane that had been in use for centuries when it was finally abolished in the ’sixties. The ballast was then shovelled into tubs and landed by cranes on shore, but the captains would dump as much as they dared into the sea when they were approaching the port, the crew being paid extra money for the work. The port authorities strictly forbade the dumping of any ballast within their waters, for it meant that they would have to dredge it up again.

When there was an opportunity of shipping chalk as ballast it was another matter. For many years the owners had regarded chalk as any other ballast, but the skippers were not long in discovering that the lime works in the North Country would buy it for one and threepence or one and sixpence a ton. A tip to the foreman of the Thameside wharf at which they were loading this ballast would enable the skippers to carry nearly as much chalk up the coast for safety as they did coal down the coast for their owners’ profit. In one coastal town several houses built by an old coaster captain have their official street name, but locally they are still invariably called “Chalk Row” -

When there was an opportunity of shipping chalk as ballast it was another matter. For many years the owners had regarded chalk as any other ballast, but the skippers were not long in discovering that the lime works in the North Country would buy it for one and threepence or one and sixpence a ton. A tip to the foreman of the Thameside wharf at which they were loading this ballast would enable the skippers to carry nearly as much chalk up the coast for safety as they did coal down the coast for their owners’ profit. In one coastal town several houses built by an old coaster captain have their official street name, but locally they are still invariably called “Chalk Row” -

IN MOUNT’S BAY, Cornwall. The schooner Snow Flake is of 109 gross tons and was built in 1880 at Runcorn, Cheshire. Her length is 88 feet, beam 21¾ feet and her depth 7½ feet.

As a rule the colliers discharged their cargo at berths in which there were no proper cranes, so that the crew was employed “jumping” or “whipping” out the coal with a block slung on the yard-

The West Country vessels generally divided their time between the fruit trade and the coasting, finishing their days on the coast altogether when they began to leak too badly for a fruit cargo. These little vessels had an advantage on the coal trade, because their finer lines and fore-

On the West Coast the most famous centre of all was Portmadoc, in North Wales, a small community which existed entirely for and by its little sailing vessels. They were not purely coasters, for they did an immense amount of overseas work in addition to their coasting trade. A favourite round voyage was to carry slate from Wales to Copenhagen or the Baltic, and to bring bottles back to Great Britain. Another was from Cadiz to St. John’s, Newfoundland, with salt for the Grand Banks fishing fleet, and then salted fish back to the Roman Catholic countries in Southern Europe. If the fish cargoes went into the Mediterranean, they would often pick up a return freight of Greek currants or Italian marble.

On the West Coast the most famous centre of all was Portmadoc, in North Wales, a small community which existed entirely for and by its little sailing vessels. They were not purely coasters, for they did an immense amount of overseas work in addition to their coasting trade. A favourite round voyage was to carry slate from Wales to Copenhagen or the Baltic, and to bring bottles back to Great Britain. Another was from Cadiz to St. John’s, Newfoundland, with salt for the Grand Banks fishing fleet, and then salted fish back to the Roman Catholic countries in Southern Europe. If the fish cargoes went into the Mediterranean, they would often pick up a return freight of Greek currants or Italian marble.

BUILT AT EAST GREENWICH in 1912, the Vicunia is a sailing barge plying on coastal routes and taking aboard various cargoes such as brick and timber. Her registered tonnage is 75.

Most of the Portmadoc fleet were three-

You can read more on “The British Coast”, “Standing and Running Rigging” and

“Thames Sailing Barges” on this website.