© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Work of Trinity House

The activities of Trinity House -

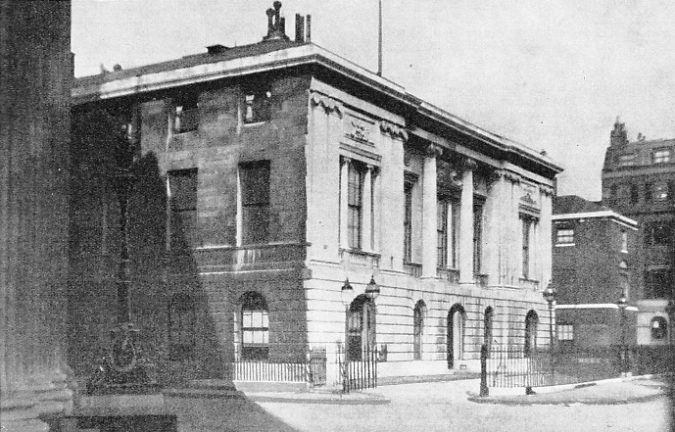

IN TRINITY SQUARE, in the City of London, stand the headquarters of the Corporation that is responsible for the safeguard of British shipping in home waters. The present building, illustrated above, was built in 1796.

IT is reasonable to claim that no organization in any way connected with shipping has a more romantic and interesting past, or a more practical present, than the Corporation of Trinity House in London. This body has a position different from that of any other organization in the world. In other countries than Great Britain corresponding duties are mainly carried out by Government departments, but some of the duties of Trinity House are individual to the Corporation.

Unfortunately it is impossible to trace back to a really satisfactory source the history of Trinity House; fire has destroyed so many of its records. It may be -

The student is on firmer ground when he claims that the Corporation is founded on the Trinity Guild formed by Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, in the twelfth century. This theory is the one generally accepted. Langton was the practical cleric-

The Guild proposed also to provide navigation marks and to help poor mariners. For many years the only lighthouses on the British coast, of which the Romans had taken particular care, were those maintained by odd chantries and monkish institutions. The light was generally a coal fire burning in an open brazier on the cliff-

Just how and when the guild came to settle at Deptford is another historical question that cannot be answered, although it is certain that a kind of college, with almshouses, existed there well before the days of Henry VIII. The college is said to have been owned by a guild of pilots and seamen who were empowered by charter to preserve seamarks, but there is no trace of this charter or evidence of the king who granted it. But there is every evidence that some body of the sort existed, for the Thames pilots were well organized towards the end of the Middle Ages. Moreover the rapid increase in overseas trade and the length of ocean voyages, brought about by the improved design of ships which facilitated beating (making headway against the wind), demanded safeguards which the Tudor sovereigns, with their appreciation of trade and navigation, were not likely to have left unsatisfied.

We are in considerable doubt as to the exact sequence of events, even in Henry VIII’s day. Tradition has it that the institution was reorganized by Sir Thomas Spert in the year 1512, and the inscription on Spert’s tombstone is that he was “Founder and First Master of Trinity House”. Unfortunately, largely because of the fire danger already mentioned, there is no real confirmation of this, although from what we know of that enterprising gentleman it is possible. Spert is described in some records as a shipwright; in 1512 he was certainly a yeoman of the Crown, drawing eightpence a day out of the petty customs of the Port of London; in 1513 he was in succession master of the Mary Rose and of the Henry Grace a Dieu, two of the finest ships in the King’s service. He was knighted in 1529 and died in September 1541.

Whatever Spert’s connexion with it may have been, it is certain that the establishment was chartered by King Henry VIII at Westminster on May 20, 1514, as the Guild of Holy Trinity and St. Clement. Apart from other evidence it is obvious that this charter was not so much an original foundation as a reorganization and an improvement.

Henry VIII’s Charter

Great attention was paid to the pilotage service of the London river. Long before 1514 the outward-

The foundation was a particular favourite of Henry VIII, who had a fine appreciation of the value of sea power. In spite of its distinctly religious character, it was left unmolested at the dissolution of the monasteries. The advisers of the boy King Edward VI, however, were not so broad-

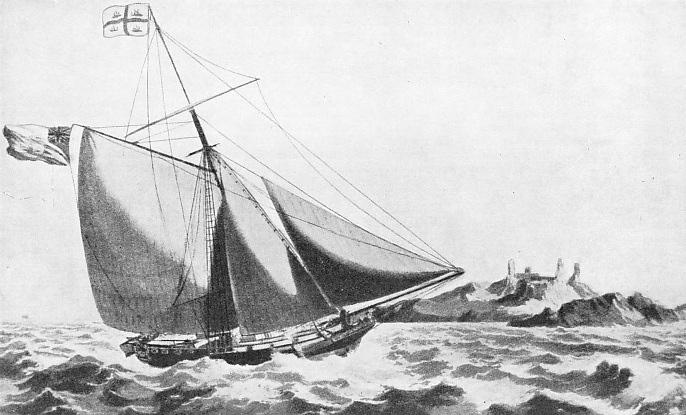

BEFORE STEAM PROPULSION became general the vagaries of the wind and the necessity of maintaining services without interruption forced Trinity House to maintain a big fleet of yachts. This picture of a yacht about 1830 shows one of the later type built for the

Elder Brethren.

Christ’s Hospital was then largely a mathematical school, and as few boys troubled about mathematics unless they intended to be navigators, the Brethren of Trinity House were called in to examine the boys of the school in navigation and mathematics. The Corporation’s experience was used also in the building of the various piers and harbours of refuge in which the Tudor monarchs were interested. On one occasion, the Brethren took action in Parliament to protect the harbours of Devonshire and Cornwall from injury through the operations of the tin miners. Queen Elizabeth found more than one opportunity to compliment the Brethren on their knowledge and their value to the nation. She was always ready to take full advantage of them, but does not seem to have taken any steps towards giving them a regular income. Although they must have charged for many of their services, it is difficult to see how they raised sufficient money for their various enterprises.

It was not until 1593 that Lord Howard of Effingham, Lord High Admiral of England and Commander-

Lord Howard of Effingham could surrender these perquisites only to his sovereign, but the enthusiastic Queen was willing to accept them with the condition that they were to be bestowed on Trinity House for ever.

James I possessed neither the knowledge nor the enthusiasm of Queen Elizabeth, but his advisers made him realize the importance of Trinity House. A new charter, granted in 1604, made great alterations. Under this charter the governing body consisted of a Master, four Wardens, eight Assistants and eighteen Elder Brethren who had the burden of management. The Corporation was also given the sole right of placing seamarks, but when the King realized that he was losing an opportunity of making money, this right lapsed.

Speculative Safeguards

Many individuals, foreseeing profit, placed lighthouses on various parts of the coast, and reimbursed themselves by charging a toll based on the tonnage of every ship that passed their lighthouse and therefore made use of it. These tolls were the main object of every speculator, but collection proved difficult and the lighthouses were generally ill administered and gave such a poor light, if they were lighted at all, that they were practically useless.

Trinity House, which was an excellent organization to take this in hand, could only stand aside and watch exclusive rights on the most dangerous coasts given to persons whose last consideration was the safety of shipping. In self-

As there was not so much money to be made out of the other sections of the Corporation it was left in peace to carry on with the training and examination of pilots, the education of navigators for the King’s service, such hydrographic work as the Navy of that day undertook, expert advice on the design of new men-

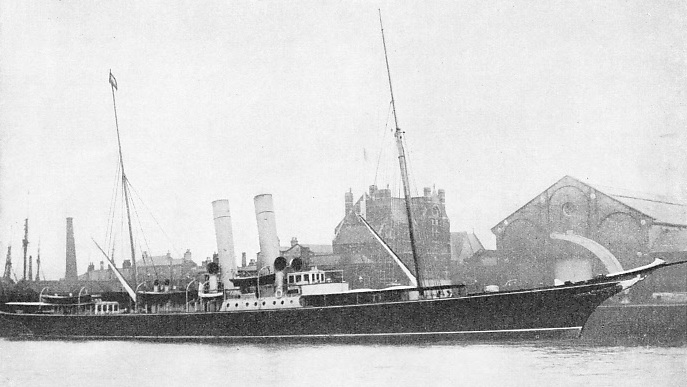

THE ELEGANT LINES of the former Trinity House yacht Irene, the predecessor of the present yacht Patricia, are shown to the best advantage in this photograph taken at the Yarmouth Depot in Norfolk. The Irene, 543 tons gross, was built in 1890, and was blown up by a mine during the war of 1914-

The only personal privilege that the Elder Brethren enjoyed in return was exemption from military and jury service. They were constantly making new jobs for themselves or, as it would appear to-

Among other miscellaneous work, in 1627 the Brethren were called upon to advise Charles I in his project of building a gigantic ship. This they considered would be too big for any port in England, and they persuaded him, for the moment, to substitute two smaller ones. In the following year they were called upon to find three hundred good seamen and twelve qualified masters for the Navy. In 1631 they subscribed £1,320 for an attempt on the North-

At the beginning of the seventeenth century they were probably the busiest and most efficient organization in the country. Although Trinity House was not a Government service at all, the Puritans were jealous of its position when they came into power. They passed an Act of Parliament in 1647 dissolving the Corporation and cancelling its charter. The work was to be carried on by a commission.

The patriotism and enthusiasm of its members, however, preserved the organization of Trinity House, and by that time there were two divisions, one at Deptford and the other at Ratcliffe, part of the modern Stepney. As soon as the monarchy was restored, Trinity House came into its own again. Charles II and his brother James fully appreciated the work that was done.

The Corporation’s First Lighthouse

General Monk, who had been greatly instrumental in bringing about the Restoration, was elected Master. To facilitate the undertaking of additional responsibilities, the headquarters were moved to Water Lane, in the City of London. The other houses were still retained. In the year of his restoration, Charles II granted a new charter on practically the same lines as that of James I; but Charles II was not rich enough to give it the boon it wanted most, the suppression of all the irregular lighthouses.

Although the Corporation flourished in the sunshine of Royal favour, it had its share of ill-

The success of General Monk as Master appears to have shown the Corporation the value of similar appointments. Some of the later appointments were merely complimentary, but others were most useful because of the enthusiasm for science and discovery which had become fashionable. John Evelyn, for instance, who was made a Younger Brother in 1673, was an amateur scientist of no little note. Samuel Pepys was made Master in 1676 and in 1685. He was a born administrator and greatly increased the efficiency of the organization. He also formed an invaluable link between the House and the Navy, and took greater pride in his office of Master than in any other position he filled.

It was during this period that the Corporation found a site where a lighthouse was badly needed for the safety of shipping and where the conditions made it too expensive for private speculators. In 1680 it set about building its first lighthouse -

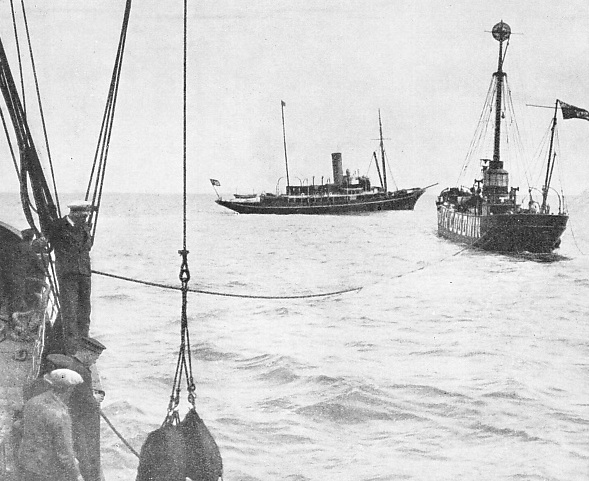

COAL FOR THE SOUTH GOODWIN LIGHTSHIP is being lowered from the deck of the Alert. The lightship is a vessel of 271 tons, and her light shows two white flashes every thirty seconds In the background is the Trinity House yacht Patricia.

At the end of the seventeenth century Trinity House was engaged in further activities. With the aid of a bequest from Captain Henry Mudd, formerly Deputy Master of the Corporation and an intimate friend of Samuel Pepys, the almshouses still known as Trinity Grounds were founded in Stepney on the model of the early Trinity House charity at Deptford. Twenty-

In the late seventeenth century the Corporation of Trinity House enjoyed the then unusual distinction of being clear of corruption. At the same time the Brethren must have been difficult to handle in committee. The Elder Brethren were all drawn from the ranks of the Younger Brethren; the Master and Deputy Master were chosen almost entirely by seniority from those who had served as Upper Warden. A fine of £10 was imposed on any qualified Brother who refused to serve as Deputy Master; for refusal to serve as Warden or as Assistant the fines were £3 6s. 8d. and £2 10s. respectively. The annual salary was £10 for a Deputy Master, £4 for a Deputy Warden and £3 for an Assistant. All meetings were held under a pledge of complete secrecy, with a fine of £10 as a penalty for the first offence and dismissal from the Corporation for the second offence. Complete silence prevailed when the Master was speaking and any Brother who used profanity had to put sixpence into the poor-

In 1714 Trinity House in Water Lane was again destroyed by fire. It was immediately rebuilt on a fine scale, but in fewer than eighty years it was in a bad state of repair. George II granted a further charter in 1730, and thirty-

From that year until 1852 the members of the Corporation were rowed in state barges from the Tower Wharf to Deptford Green every Trinity Monday to elect the Master and Wardens for the following year. Although the picturesque river trip has been discontinued, Trinity Monday is still as important day in the year of the Corporation, with its elections and special church services. The right to dredge ballast out of the Thames and to sell it to sailing ships provided the Corporation with necessary funds in its early days. By the middle, of the eighteenth century, however, ships had increased so much in size that dredging became necessary for a different reason. Trinity House maintained that the conservancy of the River Thames was a liability in the hands of the City of London, but it was willing to co-

Invasion Scare

When the Fleet at the Nore mutinied in 1797 the Elder Brethren went down the river themselves and removed all the buoys, beacons and seamarks of the Lower Thames to prevent the mutineers from navigating their ships in an attack on London. Six years later, when the country was in fear of an invasion from Napoleon, the Brethren raised a large force of trained seamen and commissioned ten frigates that had been laid up in the dockyards for lack of men. They formed a cordon across the Lower Hope below Gravesend Reach and maintained it as a defence until all fear of invasion was over. The Elder Brethren commanded the ships and kept them in fighting trim. Naval officers were appointed to take command in the event of an action, but meanwhile they were stationed in one of the Royal yachts to amuse themselves with their cards and yarns while the Brethren prepared the ships.

A CYLINDER OF GAS being lifted from the West Mouse Buoy, in the West Swin Channel of the Thames Estuary. This buoy contains two cylinders of gas as fuel for the light, which shows two quick, white flashes every ten seconds. The buoy has been lifted on to the deck of one of the Trinity House service vessels that are constantly inspecting and refuelling the beacons round the coasts of Great Britain.

The old headquarters in Water Lane were abandoned after the opening in 1796 of a new Trinity House in Trinity Square. The Corporation soon increased its scope and its reputation. When the concession and lease of Smeaton’s Lighthouse on the Eddystone expired in 1810, Trinity House took over its management and immediately replaced the old candles with improved oil lamps and reflectors. The lighthouses under the control of the Corporation had the reputation of being the best on the coast. Until 1836, however, there were still numbers of the old private lighthouses that levied independent tolls. In 1836 an Act of Parliament gave Trinity House the right to buy them all, from the Crown or from private owners, and to take over the entire control of seamarks. While this reduced the difficulties of the Corporation it certainly increased its work and the next few years were particularly active. The Duke of Wellington was appointed Master in 1837, and held this position until his death in 1852, when the water procession to Deptford was abandoned. In 1853 numerous alterations were made. The Cinque Ports pilotage service was transferred to Trinity House and the direct control of tolls and dues was transferred to the Board of Trade. In 1864 there were more changes. The care of navigation marks in the Thames was transferred to the Thames Conservancy, only to return to Trinity House in 1878. The historic right of ballast licences also went to the Thames Conservancy, and was later transferred to the Port of London Authority. At that time Trinity House had a fleet of steam dredgers and barges.

The Duke of Edinburgh, second son of Queen Victoria and a really practical sailor, became Master of Trinity House in 1866, a position in which he took great pride. Three years later the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VII, became an Elder Brother and took a keen interest in the Work. Additional duties were taken up, as well as the administration of numerous charities, and professional examination of all navigating officers for the Navy. In 1894 another sailor prince, Prince George, who afterwards became King George V, was made Master, and he held the post until he ascended the Throne in 1910. He was succeeded by his uncle, the Duke of Connaught, who had been made an Elder Brother in 1898. King George’s interest was illustrated by the Royal Warrant of 1912 which empowered the Elder Brethren to use the title of Captain and to take precedence immediately after captains of the Royal Navy. In other branches of the Merchant Service the title Captain is one purely of courtesy.

During the war of 1914-

The Brethren

The Mastership of Trinity House is still given to a distinguished layman. There is no salary attached to the position. The really active head is the Deputy Master, who is backed by nine active Elder Brethren elected from the ranks of the Younger Brethren. Of these there are about 300, admitted only after strict scrutiny of their claims. They have neither duties nor salary, but they must be masters in the Merchant Service or officers of at least Lieutenant-

Practically the whole of the cost of the work of Trinity House which deals with lighthouses, lightships and other aids to navigation is covered by “light dues”. These are levied on the ships which benefit, and are collected before the vessels leave British ports. In most other countries these costs come out of the general taxation of the country, but in Great Britain it is only the shipping industry, British and foreign, that is so taxed. The light dues are collected by the Customs and paid to the Board of Trade, on which Trinity House has to budget for its necessary income.

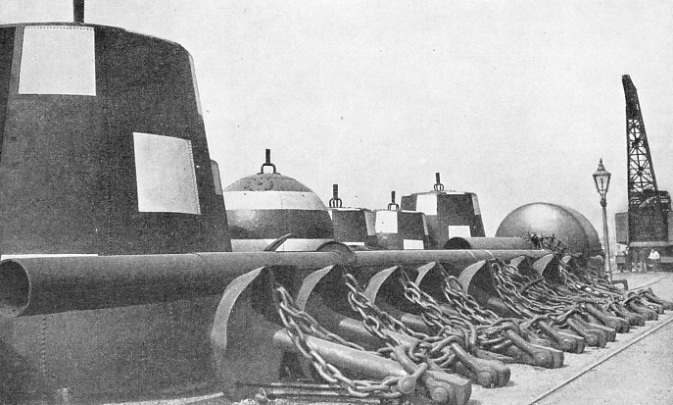

BUOYS AND ANCHORS on the wharf at the Blackwall depot of Trinity House. There are six similar depots in Great Britain, but most of the experimental work and heavy repair work is carried out at Blackwall, on the River Thames. The lamp standard shown in the

photograph indicates the size of the buoys.

For administrative and practical purposes, the Elder Brethren have divided the coast into seven districts. Every district has its headquarters, with a wharf on which gear can be stored, and from which the necessary maintenance work can be done. The repainting of buoys involves constant work, for their utility depends on their being easily recognized. At the depots an adequate percentage of spares is maintained for each type of buoy. Many repair jobs are carried out at the district headquarters, but, when a lightship is taken off her station and temporarily replaced by a relief boat, it is generally necessary to send her into a properly equipped dockyard or outside shipyard. The work in the depots is done by a small staff on permanent duty, assisted by the lighthouse men who are doing their month ashore after two months afloat.

Every district has its sea-

The tenders have black hulls and yellow funnels, and until recently, following man-

The two tenders in the London district are reinforced by the Trinity yacht Patricia. She was bought by the Corporation after the war of 1914-

Trinity House is the senior pilotage authority in the kingdom and, when the king embarks for ceremonial purposes, the Patricia has the proud privilege of leading the procession. She was bought to replace the famous Irene, which was blown up during the war by a mine in the Thames estuary.

Trinity House is the senior pilotage authority in the kingdom and, when the king embarks for ceremonial purposes, the Patricia has the proud privilege of leading the procession. She was bought to replace the famous Irene, which was blown up during the war by a mine in the Thames estuary.

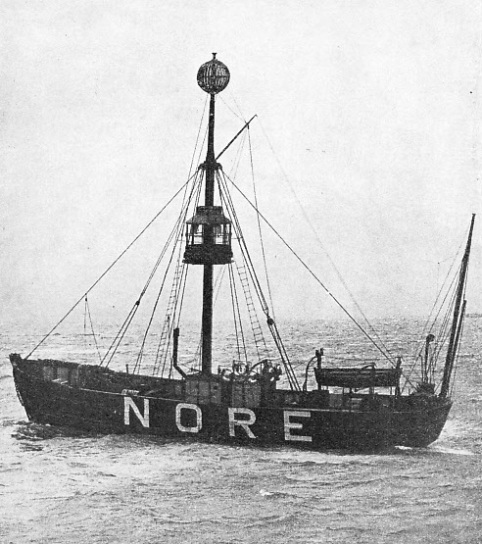

THE NORE LIGHTSHIP marks the end of Yantlet Channel in the Thames estuary. Her light, one white flash every thirty seconds, is normally visible from a distance of eleven miles. In common with other Trinity House lightships, she is equipped with a reed horn, which sounds two blasts in quick succession every two minutes during foggy weather.

The maintenance of the navigation lights and buoys round the coast of Britain is only one of the liabilities of the Elder Brethren of Trinity House. They are ready at all times to co-

In the chapter “Pilots and Their Work”, reference is made to Trinity House as the pilotage authority for London and other outports. This alone involves an immense amount of organization and hard work by the committee of Elder Brethren. There is, for instance, the regulation of the service itself, and intricate legal details may have to be adjusted when so many interests are concerned. The maintenance of the traditional high Standard demands constant care and attention. Only the right type of sailor must be admitted into the service. After selection, the Elder Brethren have to arrange for the pilots’ annual medical and professional examination. They have also to maintain discipline, settle disputes, examine accounts, and do the thousand and one other things that are -

On the boards of several of the semi-

In the Admiralty Court and certain other courts Trinity Brethren sit beside the Judge on the Bench, and under the title “Trinity Masters”, they act as nautical assessors. Although the Judges of these courts have generally been chosen after considerable experience as counsel of such specialist work, they do not pretend to be expert seamen.

In collision cases, for instance, especially where there is much conflict of evidence, the expert advice of such highly qualified master mariners is of infinite advantage in helping the Judge on matters of seamanship and other technical points. In some of the courts the Judges would be unable to conduct the eases without the help of the Trinity Brethren. In addition the Brethren are concerned in other spheres where high qualifications and specialized knowledge of the sea are of use to the administration.

In collision cases, for instance, especially where there is much conflict of evidence, the expert advice of such highly qualified master mariners is of infinite advantage in helping the Judge on matters of seamanship and other technical points. In some of the courts the Judges would be unable to conduct the eases without the help of the Trinity Brethren. In addition the Brethren are concerned in other spheres where high qualifications and specialized knowledge of the sea are of use to the administration.

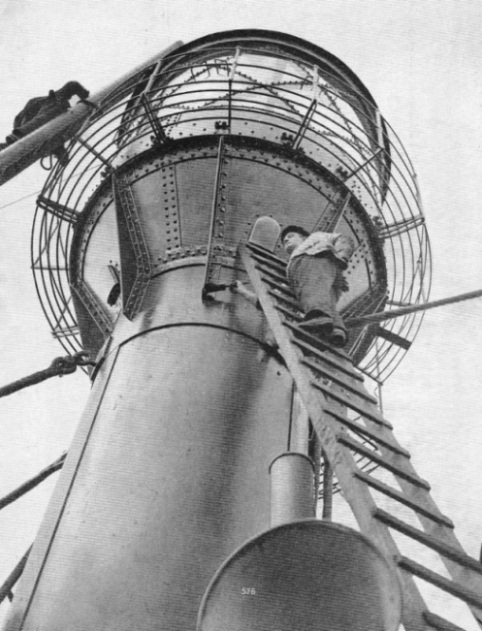

FROM AN UNUSUAL ANGLE. Painters at work on the lantern of the Outer Gabbard Lightship, during her overhaul at the Surrey Commercial Docks, London. The vessel is normally moored about twelve miles off Harwich (Essex). Her light gives four white flashes every fifteen seconds, visible eleven miles.

The present Trinity House in Trinity Square, close behind the Tower of London and overlooking the war memorial of the Merchant Service, was opened in 1796. It was designed in the Renaissance style by Samuel Wyatt. The foundation stone was laid by William Pitt, when Master of Trinity House, in 1793.

In spite of the unfortunate succession of fires which have destroyed so many of the early records, Trinity House contains an interesting museum, although few people are allowed access to its treasures. Too much work is done inside the building to encourage visitors in large numbers. The various rooms in the building are as busy as those of the most scientifically run factory, yet Trinity House maintains an atmosphere of unhurried deliberation which makes for efficiency. Many of the customs have been handed down for centuries and are none the worse for that.

Equally interesting is the Trinity House depot at Blackwall, on the Thames. This has existed for over a century, but has been extended steadily as the work of the House has become more complex. The wharf is conspicuous to passengers in passing ships by reason of the numerous buoys in reserve that are constantly being painted and repaired. Behind the wharf there is a surprising amount of space devoted to the proper care of the chains for lightships’ moorings.

In the various shops there is a wide range of machinery for all purposes for repairing the material of Trinity House, for making new fittings, and for generating the oil-

It would be easy enough to say that Trinity House is a picturesque survival recalling the guilds that were all-

The Master and Brethren of Trinity House carry out difficult work of the greatest importance to the shipping industry. Their tasks are executed with far greater economy than would be possible in a Government department operating in the traditional manner.

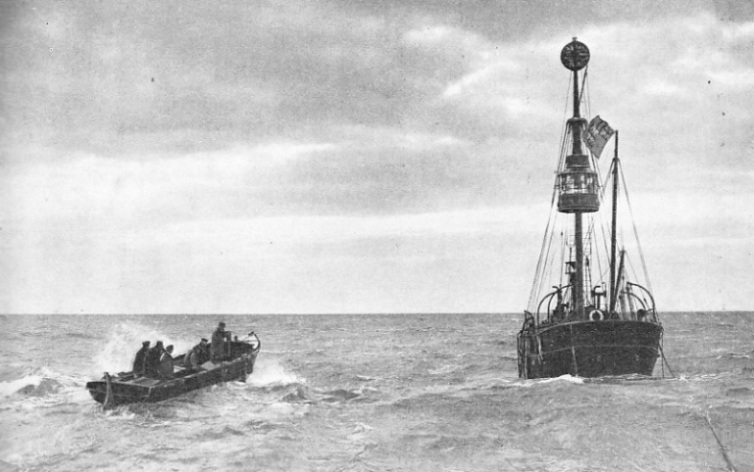

RELIEF FOR THE HELWICK LIGHTSHIP in the Bristol Channel in choppy seas. However stormy the weather may be, Trinity House must maintain efficient navigation marks to guard the safety of shipping. The Helwick Lightship shows a white flash every thirty seconds and carries a ball at her masthead. She is here seen flying the famous Trinity House flag.

You can read more on “Day and Night Signals at Sea”, “Pilots and Their Work” and

“Signalling at Sea” on on this website.