© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Canada’s Prairie Port

When the freighter “Pennyworth” sailed in 1932 to Churchill, Hudson Bay, she opened up a new commercial route to the prairie provinces of Canada. She was the first vessel to prove that the navigation of these subarctic waters was practicable for freighters

THE HARBOUR OF CHURCHILL as it was in 1933, one year after the Pennyworth arrived there. The Rio Claro, a freighter of 4,036 tons gross, is seen in the background steaming up the sea channel into the harbour. In 1933 nine ships entered the harbour; in 1934 the number was thirteen.

ON Tuesday, August 2, 1932, the Pennyworth, of Newcastle-

Clerks in warehouses can now inscribe those magic words “Via Hudson Bay” on bills of lading and feel no sense of strangeness, no quickening of the imagination. Via Montreal -

This is the story of that memorable trip. It was pioneering, the blazing of a new trail across the Western Ocean. We were bringing the humdrum into a world of romance, subduing the savage north and making it into an everyday trade route, penetrating its grim remoteness in the interests of commerce. Churchill -

The Pennyworth is a tramp cargo vessel of 5,388 tons gross. When she sailed in August 1932, she was taking us to a land of utter desolation, where nothing grows, where men live only by killing and where the pelts of wolf and fox and Arctic hare are the recognized currency.

Before leaving England we had stowed aboard a strange assortment of cargo. There were thirty-

At Antwerp there had been a further addition to this heterogeneous conglomeration of merchandise. There was almost nothing we could not have found in an emergency in the vast echoing holds where this tiny cargo of under 400 tons, for all its diversity, scarcely relieved their stark emptiness.

It was not the Eskimo, with his strong white teeth, who would chew the liquorice, and the teddy bears would never startle the native polar bears of the Hudson Bay. The goods were consigned to the south, to Winnipeg, Saskatchewan, Regina and points west. The cargo was the first to enter Canada for the prairie cities by the new Hudson Bay route.

We cleared from Antwerp on that Tuesday, at 4 pm. Sixty-

We faced the bitter fury of the Western Ocean, where it piles up in long steep seas and frequent storms and where the south-

By the morning of August 6 we were butting into a strong head-

At last the savage squalls that heralded the end arrived -

Early on August 10 we sighted our first ice -

The wireless operator soon got into touch with Resolution Island, at the north side of the entrance to the Hudson Strait. Here the first of the Canadian wireless direction-

Our skipper, wise in the ways of ice, had altered course some time before, to pass sixty miles south of Cape Farewell, the southernmost point of Greenland. He feared not only ice but also a shift of wind that might bring fog. This would have left us helpless and with no option but to heave-

Fifty-

Next day we had startling proof of the captain’s wisdom and foresight. We got in touch with a fishery supply ship which reported herself hemmed in with bergs thirty miles south of Cape Farewell -

Hitherto we had followed the path of the wandering Viking, who a thousand years before had crossed the Western Ocean in his undecked longboat in search of new coasts; but now we were in waters redolent of more recent romance and coloured by the long and daring search for the North-

Davis Strait greeted us with strong head-

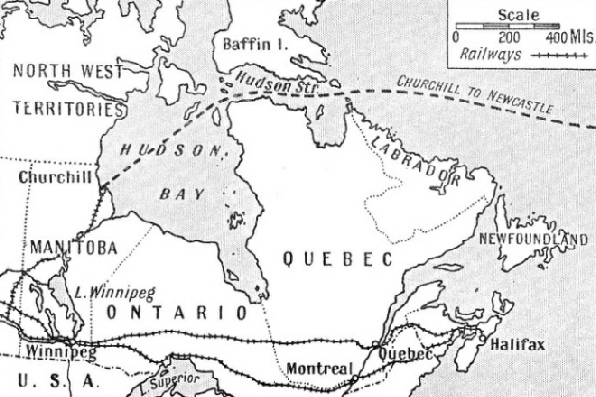

THE HUDSON BAY ROUTE to the prairie belt and Western Canada. For months in the early part of 1932 the Canadian Government ice-

The temperature was variable, and throughout the day we had spells of bright sunshine, alternating with gusts of sudden chill wind from the north. Next day the wind was icy and the bergs more numerous. The temperature fell to 38° F. and to 37° F. in the water. We picked up a message, too, from the N. B. Maclean, announcing that she was steaming east to meet us and escort us through Hudson Strait. She gave us warning of a dangerous ice-

At 1 pm we made our landfall, sighting Cape Chidley, the northernmost point of Labrador, and the Button Islands. By 4 pm we were steaming in sheltered water in sight of the wireless station on Resolution Island, where three men exist in utter isolation. These men report the movements of ice, record the weather and keep in touch with in coming and outgoing vessels. Even with powerful glasses we could see nothing but a rocky cliff-

Sunday was clear and sunny, but bitterly cold, with a keen wind coming down from the Arctic. The second great thrill of the voyage came at 10.30 am, when the N. B. MacLean hove in sight -

The ice-

At times we were surrounded by drifting ice moving rapidly eastwards with the, current. Several times we had to ring down to half speed or less for greater safety. Innocent enough those lumps of ice looked, many of them awash; but in salt water ice floats with only about one-

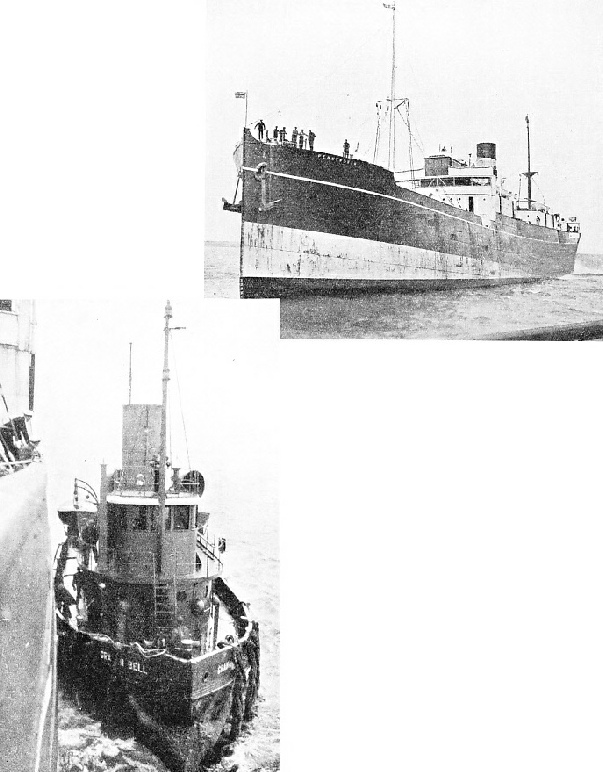

THE FIRST FREIGHTER to enter Canada’s new port. This photograph shows the Pennyworth approaching the quay at Churchill on August 17, 1932. A vessel of 5,388 tons gross, the Pennyworth was built in 1916 as the Gogovale. She is 410 feet long and has a beam of 53 ft 6 in and a depth of 28 ft 5 in. She is now registered at Montreal.

THE FIRST FREIGHTER to enter Canada’s new port. This photograph shows the Pennyworth approaching the quay at Churchill on August 17, 1932. A vessel of 5,388 tons gross, the Pennyworth was built in 1916 as the Gogovale. She is 410 feet long and has a beam of 53 ft 6 in and a depth of 28 ft 5 in. She is now registered at Montreal.

THE PILOT ALONGSIDE THE PENNYWORTH, at the entrance to the Churchill River. The pilot came aboard from the Canadian Government’s tug, the Graham Bell. The tug is a vessel of 250 tons gross, registered at Quebec, and has a length of 100 feet and a beam of 26 feet.

There are three sources of ice in Hudson Strait. The most obvious is the shore ice that forms locally along either coast towards the end of October and gradually hardens into a broad coastal belt stretching many miles out and not breaking up until late June. The middle of the strait never freezes over, perhaps on account of the currents that keep the water constantly on the move. For eight months in the year, however, it is rendered practically impassable by great ice floes carried back and forth by the tides and jamming between the two strips of coastal ice.

The second source is Arctic ice. Bergs are carried down from Baffin Bay by southerly currents along the east coasts of Baffin Island and of Labrador. Some of these bergs enter Hudson Strait through Gabriel Strait, others pass south of Resolution Island and, helped by easterly winds, are carried west to Big Isle, where they cross over to the south of the strait and are carried back out into the Atlantic at Cape Chidley.

The third source is the Foxe Channel, from which come not only local ice but also enormous floes from the Gulf of Boothia, by way of Fury and Hecla Strait. The local ice can be distinguished by its discoloration and by the quantity of rubble mixed with it, whereas the formidable Boothia ice is free from discoloration. There are four directional wireless stations supplying weather forecast broadcasts -

We passed to the south of Southampton Island (north of Hudson Bay), thus just avoiding the Arctic Circle, which runs to the north of the island; but at one point we were within about 500 miles of the North Magnetic Pole and the cold remained intense. In the afternoon the horizon ahead grew dim and a thin pencilling of haze upon it gradually extended, rising as we approached, until suddenly we were enshrouded in fog.

Ice was all round -

On this occasion, the fog lifted in two or three hours. Towards eight o’clock the sun set directly ahead of us. Fifteen minutes later we were startled to see the sun reappear well above the horizon and proceed once more to set. This time, however, there was no dazzling golden track of reflection from it across the water to our eyes. It was an ice mirage, a phenomenon of the Arctic regions that we were to observe for several nights in succession.

That night the temperature fell to 31° F, and the ship was coated with ice. The lookout in the bows, crouching behind an improvised screen of canvas lashed to the rails, must have suffered intensely; but in those waters a lookout is most essential and keen eyes are needed to spot the thin line of white in the darkness where broken water betrays the presence of drifting ice slabs.

Once during the night the engines were rung to full astern, shaking the ship violently with their vibration, as a huge berg loomed up directly in our path; but the morning was clear and the coating of ice on the decks gradually melted away. At ten o’clock, however, we ran into fog again, and now felt our way cautiously behind the ice-

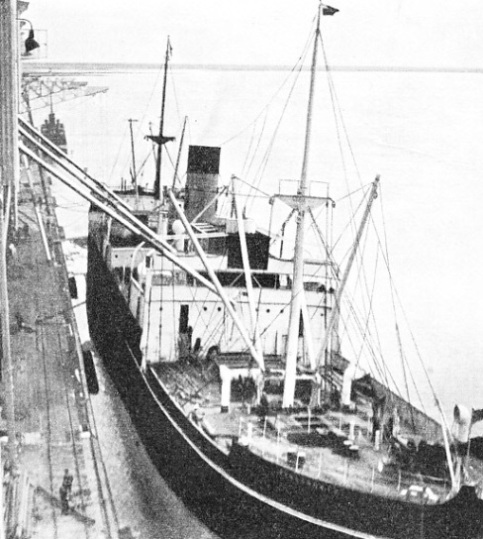

ONE OF THE FIRST GRAIN CARGOES to be loaded at Churchill went into the Pennyworth. When her holds had been cleared and the necessary shifting boards erected in them, the long pipe-

Once more the fog dispersed rapidly, and the sun burst through. The temperature rose swiftly to 45° and by noon to 54°, which seemed comfortably hot, with blue sky and smooth water and no trace of ice. We had reached the mouth of Hudson Bay.

We stopped near the N. B. MacLean. She sent over a dory and we took on board a pile of letters to be posted in Churchill. We sent the dory back with all the magazines and books we could spare and got under way once more. After a farewell salute the ice-

There are no bergs in Hudson Bay, which is considerably larger than the North Sea. Shore ice, however, forms in the extreme north. Along the east shore, the ice, three to four feet thick, stretches out to a distance of about sixty miles in winter, but on the other shores of the bay it seldom reaches more than five miles out. The succession of winter gales breaks it up into gigantic floes that move about the bay and form rafted ice, sheet piled upon sheet as the floes collide or drive ashore, so that along the coast a barrier is formed as much as thirty feet in thickness.

The exploration of the bay was begun by Hudson in 1610. He cruised right down the eastern shore, and wintered in James Bay, at the southern extremity of Hudson Bay. The following spring he insisted on exploring farther, setting a course westwards instead of heading northward for home. The crew, who had suffered privations, mutinied and cast Hudson adrift in a small boat.

Two French fur-

A Royal Charter

The success of this voyage led to the formation of the Hudson’s Bay Company -

The first trading post was built in 1668 in James Bay, at the mouth of the Rupert River. This was Fort Charles, later known as Rupert House. Other posts were established on the shore of Hudson Bay at Fort Nelson, Moose Factory, Fort Albany, Fort Severn, Eastmain and Churchill. For more than a century these posts, heavily fortified, were called upon to withstand repeated attacks by French traders and ships of war, and at one time the Company lost all but one post. The Treaty of Utrecht, in 1713, however, recognized Britain’s claim to the territory, although raiding continued. It was some time yet before the traders were allowed to carry on their work and their explorations in peace.

Early on Tuesday, August 16, we were in touch with our destination, Churchill. As we steamed south-

By 9 am we were off Eskimo Point and slowed down to take the pilot on board. He came out in a small tug, the Graham Bell, and climbed on board to greet the captain, who was dressed now for the occasion in formal uniform and gold braid.

AN OUTPOST OF COMMERCE in the Barren Lands of Canada. The magnificent new grain elevator at Churchill is capable of loading as much as 10,000 tons of grain in one day. In 1935, only three years after the Pennyworth had taken her first grain cargo on board, 2,407,000 bushels of grain were exported from Churchill to Europe.

There is little need for a pilot at Churchill. The entrance to the river is simple. A vessel runs parallel with the shore for some distance, then swings hard round to port and so sails smoothly between the low cliffs. The six-

We slid easily alongside the quay, a manoeuvre as simple with a 6,000-

Others came -

Before noon the hatches were off and the first slings of cargo were going ashore -

The grain in the elevator was of the best grade, with an absolute minimum of moisture content. When the holds had been cleared and the shifting boards erected, the long pipe-

The quay at Churchill can accommodate three large freighters at one time and the elevator can load as much as 10,000 tons of grain in a day.

Modern Navigational Aids

WE loaded 8,000 tons of grain and 800 tons of bagged flour in the ‘tween-

We were fitted with a wireless echo-

Another essential was the gyro-

A HEAVY SEA coming aboard the foredeck of the Pennyworth during the gales she encountered in the Atlantic on her first voyage from Newcastle-

Churchill, long noted for its situation in one of the best natural harbours in the world, has a long and romantic history. It was fortified in 1718, but fifteen years later the fear of its vulnerability led to the building of Fort Prince of Wales on the long promontory that guards the entrance to the river from the west side. This was one of the strongest fortresses of the north, 350 feet square, with walls 20 feet high and with heavy batteries of guns.

In 1811, the Earl of Selkirk, Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, took out a band of settlers to found the Red River Colony. The settlers were brought to Canada through the Hudson Strait and landed at York Factory, whence they struck south-

The railway from The Pas (on the Saskatchewan River), the most northerly township of any size in the province, was projected early in this century and begun in 1910, with Port Nelson as the objective. About 6,000,000 dollars (£1,200,000) were spent on harbour works at Port Nelson before the attempt was abandoned, and the railway diverted north to Churchill, a much better position for the harbour. It was not, however, until twenty-

Several important mineral fields were discovered during construction adjacent to the railway and various branch lines were built to serve them. Their future lies through the Hudson Bay route, which offers them quick and easy access to the European market, just as it offers to the prairie belt 500 miles south a swift outlet for its grain, its cattle and its farm produce.

Short Cut to Western Canada

ON the return voyage in the Pennyworth we carried thermostats in the holds and ‘tween-

At first no harbour charges were levied at Churchill, but now that the route is established normal charges are made, although these still are considerably below the cost of berthing, discharging and loading in most other seaports.

Altogether ten vessels visited Churchill in 1932 with a total gross tonnage of 46,978. The Pennyworth alone carried outward cargo and the entire fleet carried away a total of nearly 80,000 tons of grain. In 1933 nine ships visited the port. The total export of grain that year was 2,707,889 bushels.

The year 1934 saw thirteen ships at Churchill. Two of them made a quick turn round and came back for a second time. The Dalworth (R. S. Dalgliesh, Ltd) unloaded 1,576 tons of general cargo; bunker coal landed from her and two other ships brought the total imports up to 2,466 tons.

In 1935 the Wentworth (R. S. Dalgliesh, Ltd) carried out 2,582 tons of general cargo, and 2,407,000 bushels of grain were shipped to Europe. The motor vessel Leopold L-

THE FIRST SLING OF CARGO to be unloaded from the Pennyworth at Churchill contained cases of whisky. On August 17, 1932, 1,200 cases were unloaded. Other cargo included crockery, glass, cutlery, bricks, barbed wire, lubricating oil, sweets and toys.

You can read more on “Filling the Ship”, “The Great Lakes” and “The North Atlantic Ice Peril” on this website.

You can read more on “The Road to Hudson Bay” in Wonders of World Engineering.