© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Diving For £1,000,000

Weary toil and frustrated hope were the lot of the indomitable men who salvaged the gold and silver from the Egypt, which for eight years lay undisturbed more than seventy fathoms below the surface of the sea

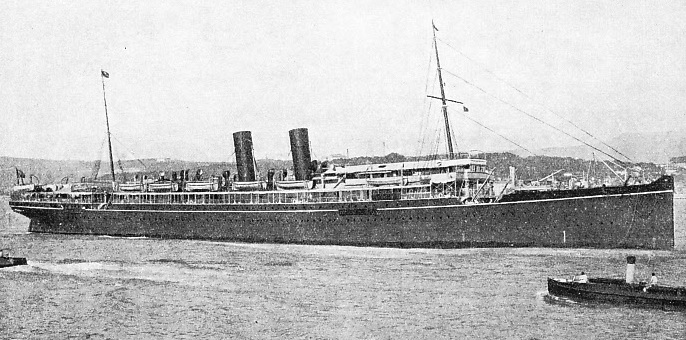

THE LOST TREASURE SHIP. On May 20 1922 the liner Egypt, of 7,912 gross tons, carrying gold and silver insured for £1,058,979, collided in the evening with the cargo vessel Seine, in fog off the French coast. The liner went down with a loss of eighty-

ONE of the biggest shocks, from every point of view, sustained by the underwriters of Lloyd’s was on May 21, 1922, when the copy of a telegram pinned to the board in the famous “Room” then in the Royal Exchange told them that the P & O liner Egypt was a total loss.

The brokers had arranged for the insurance of gold and silver bars and boxes of sovereigns for the huge sum of £1,058,979. The Egypt being a first-

It is a tribute to the safety of British liners that the premium demanded for insuring the treasure was so small -

the following afternoon and about seven o’clock in the evening the officer on the bridge heard the warning signal of another ship near by. At once the Egypt answered, but fog confuses sound as well as sight, and it was difficult to locate the direction from which the signal had come.

Those on watch peered anxiously in the murk, trying to pick up the strange vessel. Suddenly she was sighted steaming straight down on the liner and in fifteen seconds her massive stem was shearing an enormous hole into the side of the Egypt. The liner seemed about to roll over and sink, but she swung back after the first impact and gave Captain Collyer a chance to launch lifeboats. Although the crew worked heroically to save all the passengers, the respite was too brief. In fewer than twenty minutes after the collision, the shattered liner went down with fifteen passengers and seventy-

That tragic telegram to Lloyd’s brought in its train a claim of over £1,000,000 for the lost treasure. The underwriters and marine insurance companies admitted the claim without hesitation, and the integrity and financial strength of Lloyd’s was once again proved when ten days later the whole sum was paid.

But that was not all. The shippers of the treasure had put more on board the Egypt than was covered by the contract, and this surplus, owing to an oversight, was not insured. In the ordinary way the loss would have fallen on the shippers. As soon as the discrepancy was discovered, the broker explained the position to the underwriters. Although so badly hit, they at once agreed to admit this extra treasure as though it had been insured, and their generosity cost them a further £20,000. There is a widely-

The Egypt's underwriters were not hopeful of obtaining from the bottom of the sea the gold which had become theirs on the payment of over a million pounds of insurance. The position where the ship sank was not known with certainty, since fog and the distance she had travelled after she had been struck made it impossible to indicate the exact spot.

The Egypt's underwriters were not hopeful of obtaining from the bottom of the sea the gold which had become theirs on the payment of over a million pounds of insurance. The position where the ship sank was not known with certainty, since fog and the distance she had travelled after she had been struck made it impossible to indicate the exact spot.

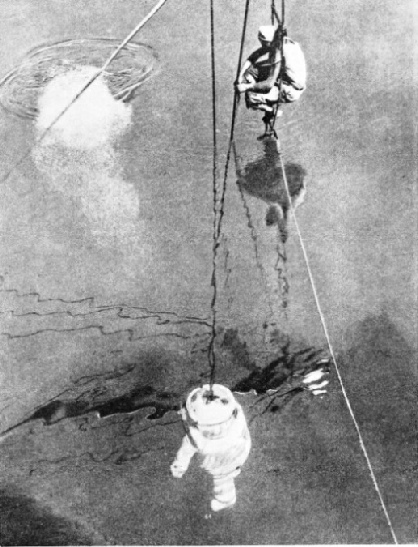

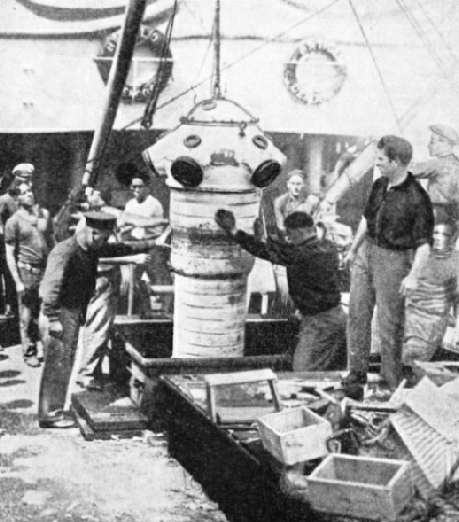

DESCENT INTO THE DEPTHS. The remarkable illustration shows a diver going down to inspect the wreck of the Egypt from the Italian salvage ship Artiglio. The normal diving suit was not employed on this task. There was used instead an observation chamber, shaped in the manner of a cylinder and tested to withstand pressures down to 900 feet below the surface. The apparatus was equipped with cylinders of oxygen, a telephone and ballast tanks, into which sea water could flow to weight the dress and take the diver down.

Moreover, the sea-

Realization that the Egypt was lying somewhere off the French coast with this huge treasure induced some people, who were possessed of greater optimism than knowledge of salvage work and the difficulties entailed, to approach Lloyd’s in the hope of obtaining a contract to raise the gold, but they failed to convince the underwriters.

Mr. C. P. Sandberg, a well-

It was a sound idea, which impressed his guest, and out of that after-

This extensive sweeping of the sea-

This suit, likely to give a child a nightmare, was a grotesque-

This suit, likely to give a child a nightmare, was a grotesque-

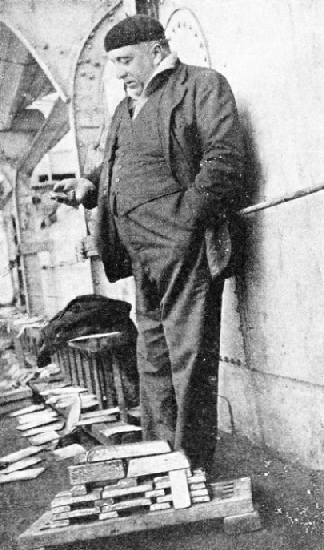

PERSISTENCE REWARDED. On June 22, 1932, after loss of life and many months of fruitless labour, members of the Italian salvage concern Sorima saw two golden bars arrive on the deck of the salvage vessel amid mud and debris. In this picture the Italian leader, Commendatore Quaglia is seen standing by the first gold bars recovered. A few hours later bullion worth £80,000 was picked up.

Soon after this dress was constructed the late Colonel K. M. Foss, who made so many attempts to recover the Armada treasure which he was convinced lay at the bottom of Tobermory Bay, came to the writer in a state of enthusiasm to tell him all about it. His ideas for acquiring the English rights did not materialize. But the dress was sent to England when the British submarine M.1 sank off Start Point in 1926, and the German diver was lowered in it to try to help salvage the sunken craft. Unhappily the sea was too rough, the. diver being shaken and bruised by his ordeal, and, after two ineffectual attempts, operations with, the dress were suspended.

An American naval officer gave a good account of a diver’s performance in this dress which he saw in Germany. Its possibilities led the Italian salvage concern known as Sorima to acquire a dress for experimental purposes on salvage work in the Mediterranean. The company trained its divers Gianni and Bargellini and others in its use and began operations in Rapallo Bay, where the American steamer Washington lay on the bottom in fifty-

Commendatore Quaglia of the Sorima company was determined to see what he could do with the German dress. It was a pioneer attempt and, although Commendatore Quaglia was hopeful that some good might result, he had no practical knowledge of how the dress would work. Extreme pressure might pinch the joints and make arms and legs immovable, or they might work with ease.

From their experience the Italians gradually developed a technique. They saw that special machines were required to do the work which could not be done by the man in the suit. As these machines did not exist, they invented them. They made strange-

The Italians continued to increase their experience by working on the Washington, and in 1928 the two Englishmen decided to give Sorima the contract for salving the Egypt’s gold. But that firm was not yet prepared for the task. It was anxious to improve its methods and at the same time clear all the cargo out of the steamer in Rapallo Bay.

As the company’s officers were working close to their home port of Genoa they could easily return to headquarters for equipment. They took from the wreck thousands of tons of metal, including 400 tons of copper and 600 pairs of railway carriage wheels and axles. Their crowning feat was lifting out a number of locomotive boilers which were so unwieldy that they were difficult to handle on solid ground. By the time they had finished, the Washington had ceased to exist as a ship, and Sorima had recovered 7,000 tons of metal from her to pay their expenses and provide a margin of profit.

Seeking more profitable work in the Mediterranean to improve their efficiency before facing those difficult tides and currents, off the coast of France, where the Egypt lay, they began methodically on another ship that promised to reward them for their time and trouble. Here they lifted 250 tons of zinc and 450 tons of copper, as well as many tons of steel billets.

The new apparatus was now being used with great efficiency and cargo was being taken from ships lying at depths that had never been reached before. Commendatore Quaglia saw the necessity of establishing a close understanding between his men. He taught them to work in unison, since perfect team work was essential in such deep water.

Cables that Snapped

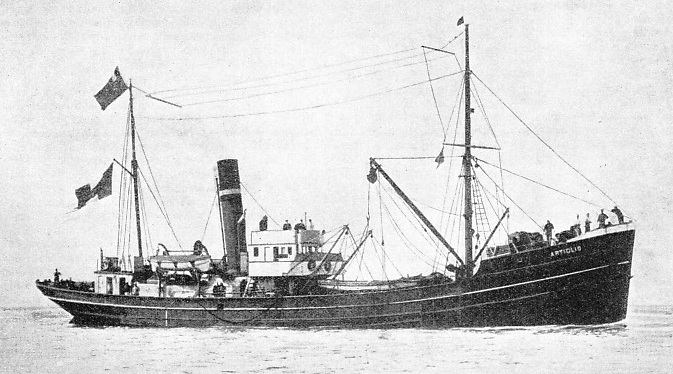

In 1929, having decided to search for the Egypt, he took his salvage ships Artiglio and Rostro through the Straits and established his headquarters for the season at Brest. Before the Egypt had sunk her wireless operator had sent out a call for help, which gave a bearing to the nearest wireless station on the coast. The difficulty was that no one knew what distance she had covered from the time she was struck until she sank, and a further complication was that it was impossible to judge the direction in which she had moved.

The likeliest spot having been fixed after a careful study of the evidence, the ships were sent out with a mile of cable dragging on the sea-

The likeliest spot having been fixed after a careful study of the evidence, the ships were sent out with a mile of cable dragging on the sea-

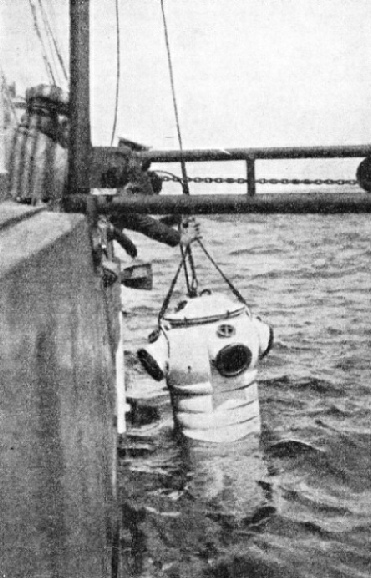

THE SPECIAL OBSERVATION CHAMBER, containing a diver, being lowered over the side of the Artiglio above the spot where the Egypt lay. The wreck was discovered by means of a sweep. This sweep consisted mainly of a cable carried on a series of buoys between 25 and 30 feet above the sea-

They consulted Captain Hedback and searched carefully where his sweep had caught on the obstruction. They employed the captain of the Seine to take them out to the spot where he judged that the collision had occurred, and combed the sea-

When bad weather forced them to discontinue their search, they put into Brest for stores and then ran down to the sheltered side of Belle Ile to investigate the Elisabethville, a sunken Belgian steamer which was stated to have had a valuable parcel of diamonds in her safe when she sank.

They found her with little trouble in 240 feet of water, and a diver went down to explore. Eventually the safe was hauled up on deck, but, to the disappointment of the crew, it did not contain a single diamond. What happened to the gems remains a mystery, but there is little doubt that they were not in the safe when the ship went down, for at 240 feet it was too deep for anyone to reach it before the Italians. Eight tons of ivory tusks, however, justified the salvage.

When favourable weather set in during the summer of 1930 the salvage ships continued their search. The rocky pinnacles on the sea-

Seventy-

The monotonous task continued and, despite a widespread opinion in interested circles ashore that the ship would never be found, nothing could shake the faith of the commander. To the joy of all, on August 30,1930, the crew found a wreck which they believed to be the Egypt. Three miles from the position that the French captain had marked in the chart, it was on the edge of the area in which they were sweeping. It was particularly gratifying to the commander, for it was a spot which he had finally worked out from the bearings taken by the wireless stations at Ushant and Pointe du Raz.

Sure in their own minds that they had found the Egypt, the crew sought to confirm their views and find convincing evidence for all doubters. Getting into his observation cylinder and assuring himself that everything was in working order, Bargellini was shut in and dropped over the side. He had a telephone to talk to those in the ship and plenty of oxygen in the containers. The chamber was lowered gently until it was half immersed, and there it hung partly in the sea and partly out while Bargellini allowed its ballast tanks to fill with water. Owing to the air space inside, weight was necessary to take it to the bottom; otherwise it would have bobbed about in the fashion of a corked bottle.

The diver was lowered, and the light became dimmer as the surface slid farther away. Those on deck watched anxiously as he passed the sixty-

Bidding them raise him a few fathoms, he swayed there in the semi-

FOR USE AT RECORD DEPTHS. The diving chamber used to locate the Egypt being lowered into the hold of the Artiglio. The chamber was of Italian design, made for operation at extreme depths, and the divers had to be trained to use it. Experience was gained by working on the American steamer Washington, which lay on the bottom in fifty-

Commendatore Quaglia was convinced by all his experience in the Mediterranean that the amount of work a man could do at these depths was almost negligible. The metal diving dress was therefore not suitable for the Egypt. In its place they used an observation chamber resembling a cylinder which was invented by Sorima and tested to withstand pressures down to 900 feet below the surface. Thus they assured themselves that a diver working at, say, 500 feet would not be killed by the pressure crushing or bursting the observation chamber. As already mentioned, the dress was equipped with cylinders of oxygen for the diver to breathe, a telephone through which he could talk to those on the ship, and ballast tanks into which sea water could flow to weight the dress and take the diver down. Otherwise the diver was only an observer and could merely give instructions. He was imprisoned in his cylinder and had no means of doing anything outside the observation chamber.

The miracle of salving the gold from the Egypt was carried out solely by executing the orders of the man cooped up in the observation chamber. He told the men above what to do, when to drop their grabs or to lower the explosives. His voice came up to them -

Sometimes a grab was dropped many times before it reached the correct spot. Often a mere touch would have set it where the diver wanted it to go, but he could not give it that touch. Instead the men above would have to haul up the cable slightly and, as they, hauled, the salvage ship Arliglio might roll a little to a wave and swing the grab into a worse position than before.

It was a terrible task, so difficult that it is a wonder that it was ever successfully concluded. The work called for patience all the time above and below, and it is doubtful who was more to be pitied -

Many a time the diver watched the grab swinging gently over the hole into which he intended it to drop, and often when he gave the order to lower they obeyed a fraction of a second too early or too late, and the gentle swing of the grab would move it out of position and compel them to repeat the manoeuvre.

After that first dive the news went out that the liner was found. So much scepticism still existed that the Italians determined to settle the matter by taking into port something tangible as proof. Deciding upon the captain’s safe, they began their operation to break into the cabin and remove it.

Their method of using explosives to shear away portions of the ship was to fix the charges to battens, which were duly weighted and lowered repeatedly until they were on the required spot. The diver having been hauled up out of the way, the charge would be fired by electrical contact, and the diver would go down again to see whether his aim had been accomplished. In this way they cut away a three-

Bullion

After much trouble and the use of a number of charges, the diver reported that a gap had been cut into the captain’s cabin. The diver was anxious to see what was there, and his orders went up to those above until he was suspended over the hole. Another order and he was swinging gently inside the cabin itself, those on deck carefully manipulating the diving chamber. The diver stared eagerly out of the front window, and then the side, in his efforts to penetrate the gloom. Slowly the cylinder turned and he saw the captain’s safe before him.

Further orders brought down a special pair of grips resembling the beak of a gigantic parrot, invented for working in just such a narrow place as this, where there was little room to move. The man in the cylinder watched those grips gaping in the semi-

Several times he suffered the disappointment of seeing the implement drop almost into position; then, to his joy, it came down gently square on the top of the safe, its steel grips opening wide over the sides. He watched them closing as the cable in the centre was pulled until the grips caught the smooth sides. He could hardly breathe as the implement began to take up the weight of the safe. Slip, slip, went the grips -

By good fortune the grips held the safe securely until it reached the surface, when those on the Artiglio saw that they had slipped to within an inch or two of the top edge and feared to see it slip completely. But the derrick pivoted quietly and the safe was on the deck.

By good fortune the grips held the safe securely until it reached the surface, when those on the Artiglio saw that they had slipped to within an inch or two of the top edge and feared to see it slip completely. But the derrick pivoted quietly and the safe was on the deck.

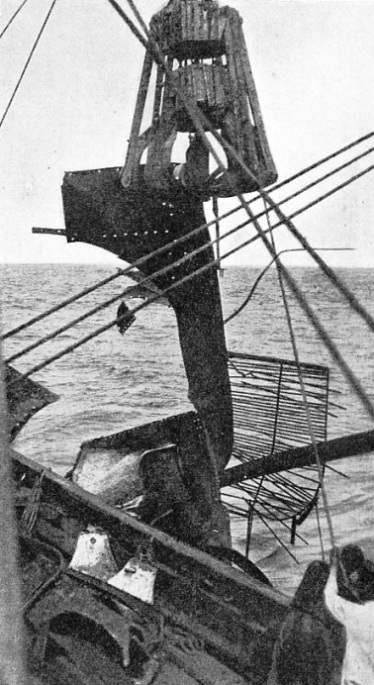

WRESTED FROM THE OCEAN. A grab of the Artiglio coming up with some of the steel wreckage from the Egypt, which was broken up by explosives. The modern miracle of salving gold from the sunken vessel was effected by the orders of the man in the diving chamber, who directed the casting of the grabs and the lowering of the explosives. The method of salvage adopted was to cut the ship away with explosives, shearing the steel sides and decks, and lifting tangled plates until the grabs could reach down into the strong-

Sealing the safe, they raised the observation chamber and steamed to Brest, where the British Consul watched while it was opened. The first thing they found was the Foreign Office correspondence which had been sent by the Egypt, thus establishing the identity of their wreck. There was also a key labelled “Bullion Room”, which was, of course, useless to them.

A project was mooted to cut the ship across and lift out the strong-

Imagine a man dangling on the end of a wire rope 400 feet in length. A slight movement on the surface might make him swing in the manner of a pendulum. On fine days the light filtered down to create a dim twilight that enabled him to see for a few feet in front of him; on dull days it was sometimes quite dark. In the early dives as he swung within radius he could just catch an occasional glimpse of a massive dark steel wall which told where the ship lay.

In good weather the diving cylinder was kept in position with anchors, but these did not eliminate all movement in choppy weather. Another annoyance was that an appliance would frequently swing away from the man in the observation chamber. Swinging up to the left, he would catch sight of the grab moving back to the right. This difficulty was overcome by making a connexion between the cables of the appliance and the observation chamber, so that, should they swing, they would both do so in the same direction. By cleverly mooring the salvage ship to six buoys the whole ship could be moved slightly to get into the right position for carrying out the orders of the man below.

A fortnight of splendid weather enabled them to work from daylight to dark, and considerable progress was made in cutting away the first deck of the ship. When bad weather heralded the end of their working season, they hauled in their buoys, put down their winter buoys over the wreck and steamed to Brest, hoping in the following season to reach the gold.

Instead of laying up the salvage ships for the winter, Sorima had arranged with the French Government to remove an old American munition ship, Florence H, which rested in 50 or 60 feet of water in the channel between Belle Ile and the mainland. Although it was in the tempestuous Bay of Biscay, the island itself gave shelter to the position even in winter, and the salvage men, who had been working at 400 feet or so in the open, regarded a job at 50 or 60 feet with little concern.

An explosion had carried the Florence H to the bottom in 1917, but it was not known whether her cargo, if it still existed, had been rendered innocuous by immersion in the sea for so many years. The Italians, who had been working with explosives for years, were not prepared to take risks. Attaching their first charges, they steamed more than a mile away for safety, and touched them off. All having gone as planned, they proceeded to lay further charges, drawing nearer to the wreck after each explosion as they became convinced that there was nothing to fear from her, until only about a hundred yards separated them from the sunken vessel.

On December 7, 1930, charges were laid to cut down the stern. The diver ascended and Gianni, who held the switch in his hand, made contact to set the charges off.

That was the end of the world for Gianni and most of those on board. A mighty concussion shook the heavens as the remaining cargo in the hulk went off. The sea heaved up and engulfed the Artiglio. Smoke and flame shot hundreds of feet in the air and filled with terror the French people on the mainland thirty miles away. Of that matchless salvage crew only seven survived. The sister ship, Rostro, two miles away, was unharmed. Her crew saw the black smoke spreading out after the disaster and managed to pick up the few survivors.

The loss of the Artiglio and her special apparatus was a sad blow to Sorima, but it was nothing compared with the loss of the men. They had been trained for years to work together and they alone were experienced in deep-

But the work had to continue. Commendatore Quaglia looked round him, picked a likely man here and another there, trained them in the use of the special apparatus until he had moulded them into another fine team to carry on the salvage of the Egypt's gold.

Next season they steamed out in a new and bigger Arliglio, equipped with improved apparatus, including handy cranes for lifting heavy material and a variety of peculiar grabs for working in difficult places and lifting unusual objects. Among these grabs was one so constructed that, after its fingers closed together at the bottom, a metal cover resembling an inverted umbrella came into position beneath the fingers, so that, should a salvaged bar of gold slip, it would fall into the metal guard and be brought safely to the surface.

Next season they steamed out in a new and bigger Arliglio, equipped with improved apparatus, including handy cranes for lifting heavy material and a variety of peculiar grabs for working in difficult places and lifting unusual objects. Among these grabs was one so constructed that, after its fingers closed together at the bottom, a metal cover resembling an inverted umbrella came into position beneath the fingers, so that, should a salvaged bar of gold slip, it would fall into the metal guard and be brought safely to the surface.

DEEP-

The success of the Italian salvage team was not the result of chance, but sprang from hard work and careful attention to detail. All possibilities that could be foreseen were considered, and everything that human ingenuity could devise to help the work forward was carried out. Their quiet confidence came from their attention to detail.

Early in July, 1931, the new team managed to cut through the promenade deck. This was good progress, for it left only the upper deck and main deck to cut through before the strong-

Everyone on board was eager to reach the gold that year. The season was passing, and the work developed into a race between the team and the weather. Seizing every opportunity, working sometimes when the diver in the observation chamber could barely see, they managed to blast away a portion of the main deck to breach the roof of the treasure chamber, where the metal seemed particularly unyielding. Just before the light failed one evening they dropped the observation chamber over the opening in the roof to give the diver a glimpse of the strong-

In May, 1932, Artiglio II took up her position over the Egypt, and for several weeks grabs were busy clearing the great hole in the ship of debris swept in by the winter gales. The weather was not good, but towards the middle of June they saw rifles, cartridges and rupee notes fall from the grab to the deck -

Impatiently for several days they watched the grab’s haul until, on June 22, two golden bars thudded to the deck amid mud and debris, and all their pent-

Conditions remained good all through Friday and until Saturday afternoon, during which time they recovered gold worth £180,000. As the weather was changing, Commendatore Quaglia sent a message to Lloyd’s and steamed for Plymouth, where among those to greet him were Sir Percy Mackinnon, then Chairman of Lloyd’s, and Sir Joseph Lowrey, Secretary of the Salvage Association.

Up to that time the Italians had spent £150,000 on the work, having combed the sea-

On June 28, Artiglio II left Plymouth again, but the weather was unfavourable all through July, and it was not until the second week in August that it grew calm enough for work. But during a short period they hauled out treasure worth some £20,000, which was landed in Plymouth on August 14. They had another lucky spell before the end of August, when they brought up gold, silver and sovereigns valued at £190,000. In these three short periods more than half the Egypt’s treasure -

The treasure hunt was resumed in 1933, and five lucky spells yielded bullion to the value of £206,000. There was an unexpectedly fine spell as late as November, which enabled them to lift £8,000 worth of gold. The following year found Artiglio II moored over the wreck once more, clearing the wreckage from the broken ship and grabbing for the remaining gold. In August they had splendid results and recovered treasure worth £160,000; September yielded a haul worth £30,000.

On July 13, 1935, Artiglio II put into Plymouth for the last time, when she landed gold worth £30,000.

The value of the treasure recovered was about £1,183,000; thus the Italians gained a rich reward for their ingenuity. Their modern methods won them the record for deep-

A TRIUMPHANT RETURN. The salvage ship Artiglio II steaming into Plymouth with gold rescued from the Egypt in her hold. The sum of £150,000 was spent on the task, which occupied two seasons spent combing the sea-

You can read more on “Diving Adventures” and “Dramas of Salvage” on this website.