© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Caledonian Canal

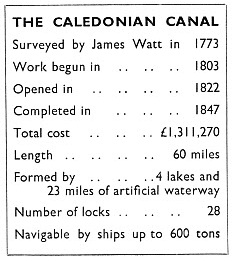

First planned by James Watt in 1773 and opened to shipping in 1822, the Caledonian Canal is chiefly used to-

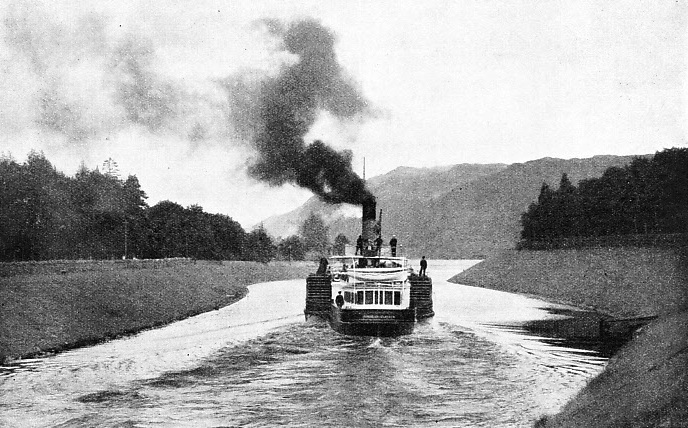

HALF HER JOURNEY FINISHED. The paddle steamer Gondolier leaving Fort Augustus, which is situated at the head of Loch Ness and marks the mid-

THE Highlands of Scotland are cut completely in two by Glen More, the Great Glen. This is a straight cleft, roughly seventy miles in length, running from Loch Linnhe, above the island of Lismore, in a north-

If Nature had not made this unusual geological feature, a deep furrow running across the Highland plateau, the Caledonian Canal would certainly never have been built; for in the Great Glen lies a series of long, narrow lakes. Nearest to Inverness is Loch Dochfour, a small freshwater lake. This is separated from Loch Ness only by a narrow strip of water. Loch Ness is more

than twenty-

The straight, open length of the Great Glen appears to be favourable for the construction of a canal, particularly as the glen contains the four lochs which occupy more than half its length. At the northern end, however, Loch Ness is 50 feet above sea-

James Watt, the famous steam engineer, was the first man to make plans for the construction of the Caledonian Canal. The canal was intended to eliminate the long and dangerous passage through the Pentland Firth and round Cape Wrath, and to make possible a direct service of fast packets from Inverness to the Clyde. Ships were often delayed for months on the north coast of Scotland. In 1773 James Watt surveyed the glen and estimated the cost of the canal at £165,000. Nothing was done for twenty years. Then another survey was made by John Rennie, whose Waterloo Bridge, opened in London in 1817, was not dismantled until 1935. The Government took no action concerning the canal, however, until matters were suddenly brought to a head by the Napoleonic Wars.

The activities of French privateers against merchant ships gave rise to a number of ship canal schemes intended to protect unarmed vessels. The Caledonian Canal proposal came once more before the public eye. It was to be part of a much wider scheme for the “improvement” of the Central Highlands.

Thomas Telford, a friend of Watt, was called in, and with Jessop as consulting engineer he made a new survey of the route. Telford estimated the cost at not less than £500,000, but the urgency of the danger to merchant shipping made the Government accept his plans. The Caledonian Canal Commissioners were incorporated by an Act of 1803. Work was begun in the same year, with Telford as Engineer. The waterway was to allow for the passage, from coast to coast, of “a fully equipped 32-

The canal was nineteen years in construction, and when it was ready for use, the cost had grown to almost double Telford’s estimate.

The canal was nineteen years in construction, and when it was ready for use, the cost had grown to almost double Telford’s estimate.

The Napoleonic scare was long past by the time of the opening, and only a fraction of the expected number of ships used the new short cut. Telford was bitterly disappointed, He died in 1834, and his great work fell into such disuse that in 1837 the Government nearly closed the canal indefinitely. In that fateful year, however, James Walker succeeded in inducing the Government to spend an additional £300,000 on improving, or rather completing, the work. The canal was closed for this purpose, and in 1847 it was reopened. In the following year, the Crinan Canal, on the west coast near Ardrishaig, came under the control of the Caledonian Canal Commissioners. The final cost has been reckoned at £1,311,270, although the scheme was originally abandoned because Watt’s estimate was considered too expensive.

The middle of the nineteenth century was the most prosperous time for the Caledonian Canal. In one year more than 500 ships sailed between Clachnaharry and Corpach “in an almost unbroken line”. Until the completion of the southern main line of the Highland Railway in 1865, the canal formed the only direct route for passengers and freight in bulk between Glasgow and Inverness. When the present system of railways in the Highlands was completed, there were still four steamers engaged on internal canal passenger traffic alone. No railway lines were built to follow the course of the canal throughout its length, although one line ran from Fort William to Fort Augustus at the southern end of Loch Ness.

There are no longer any passenger train services in the canal area. The MacBrayne paddle steamer Gondolier, 173 tons gross, carries tourists through the Great Glen every summer.

The canal itself is only four miles longer than a dead-

A trip from end to end of the Caledonian Canal is an interesting experience. The steamer starts from Banavie Harbour, at the southern end of Loch Lochy. Cargo ships, however, enter the canal directly from the sea loch at Corpach.

The southern entrance of the canal is situated in the angle formed by the junction of Loch Eil and the upper part of Loch Linnhe. In the south-

A special sea-

From Banavie there follows a cut 6⅛ miles in length to Gairlochy, where there are two more locks. Thus the canal reaches the first of the chain of lakes that it connects. The level ol Loch Lochy has been raised 12 feet by damming the River Lochy and diverting the outflow into the River Spean. Several mountain streams, which threatened to interfere with the canal, pass under it in culverts between Banavie and Gairlochy. The fertile valley of the Lochy is in the centre of ancient Lochaber, a district whose history has been rich and eventful.

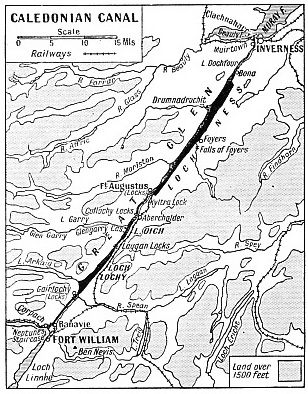

THE CALEDONIAN CANAL is almost straight throughout its length and was the only direct route between Glasgow and Inverness for passengers and freight in bulk until 1865. In that year the southern main line of the Highland Railway -

The passage of Loch Lochy, as that of Loch Ness, is always a thing to be remembered. The glen may be smiling in sunshine, grim in storm and squall, or weird and sinister under curtains of misty rain.

Loch Lochy and Loch Oich are connected by a cut only 1 mile 65 chains in length. It contains two more locks, one to allow for the “climb” to the canal’s summit level on Loch Oich, and the other a regulator to allow for Loch Oich’s periodic rise and fall. Loch Oich, being small and shallow, is more drastically affected by a sudden spate than are the great deeps of Loch Lochy and Loch Ness. Loch Oich is a lovely sheet of water, set with several islets. On a rocky promontory stands Glengarry Castle, now only an empty shell.

Early Paddle Steamers

At the northern end of Loch Oich comes another cut, beginning with Cullochy Lock near Aberchalder. This stretch is 5 miles 35 chains long, with locks at Cullochy (Aberchalder), Kyltra and Fort Augustus. At Fort Augustus there is another “staircase” of five locks, bringing the canal down to the level of Loch Ness. Apart from its mountain setting, Fort Augustus is most notable for its wonderful Benedictine Monastery, on the site of the fort founded by General Wade in 1729.

Loch Ness is remarkable for its great depth and the fact that it has never been known to freeze. Soundings show it to be 150 fathoms deep, a depth exceeded in Scotland only by Loch Morar, and by only a few lakes on the European Continent. Loch Ness, with its long, mountainous sides, is a superb stretch of water. On the southern side, roughly halfway up its length, is the pier and village of Foyers, famous for its waterfalls. At Foyers, too, are the works belonging to the British Aluminium Company, connected with the loch by a short private railway line. All the heavy equipment in the works, and the locomotive, were brought by steamer through the Caledonian Canal, the only practicable means of transport.

There is a small cut from Loch Ness to Loch Dochfour where there is a regulating lock and a special escape for salmon fry. The final cut from Loch Dochfour to Clachnaharry and the open waters of the Beauly Firth is 6 miles 35 chains in length, with a series of four locks going down at Muirtown. At Clachnaharry the canal is carried for 400 yards out into the Firth between artificial embank-

Two interesting old steamships have for years been associated with the passenger service between Banavie and Inverness. The paddle steamer Glengarry was one of the first steam vessels to ply on the canal. She began her long career in 1844, when she was built by Smith and Rodger primarily for the Clyde services, and was named the Edinburgh Castle. In 1875 she was bought into

the Hutcheson-

The paddle steamer Gondolier was built specially for the Caledonian Canal service in 1866. She is an iron-

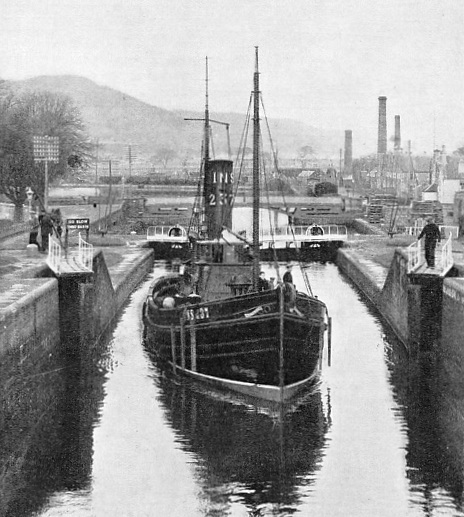

AN INVERNESS DRIFTER, the Invernairne, passing through the locks at Inverness. The vessel, which belongs to the Moray Firth Fishing Fleet, is on the first stage of her sixty miles’ journey through the canal. She is bound for the fishing grounds off the west coast of Scotland where she will make Oban her base and harbour.

You can read more on “Britain’s Canal System”, “The Kiel Canal” and “The Manchester Ship Canal” on this website.