© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

With the Fleet at Sea

A first-

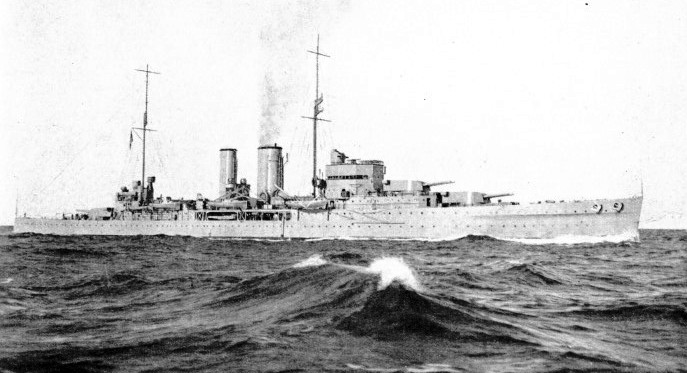

COMPLETED IN MAY, 1931. H.M.S. Exeter is one of the finest modern British cruisers. Her standard displacement is 8,370 tons overall length 575 feet, beam 58 feet, and draught 17 feet. She carries six 8-

ALTHOUGH fighting ships do not remain continuously at sea, but spend a good deal of time in port, it is none the less true that the sea is the Navy’s natural element, in which it lives, moves, and has its being. If we wish, therefore, to acquire a real knowledge of the Navy, to discover what it is and to appreciate what it does, we must accompany it to sea. Let us, then, imagine ourselves on board a battleship of the Home Fleet, which is to be our home for the next two months or so, according to the duration of the autumn cruise which is about to begin.

Our battleship, a unit of the Queen Elizabeth class, is moored in Portsmouth Harbour. For the past fortnight she has been busily taking in provisions and stores of all kinds, sufficient for a three-

Our ship, which belongs to the Portsmouth Division of the Home Fleet, is due to leave harbour at eight o’clock the next morning, immediately after the flagship Nelson. Cruisers and destroyers will follow us, and in the course of the day we shall rendezvous off the Isle of Wight with the ships of the Davenport Division. Twenty-

The night before sailing is a busy time for all on board, but especially for the Commander; as chief executive officer, he is responsible, under the Captain, for seeing that everything is in apple-

Next day, before dawn, the great battleship is a hive of activity. Breakfast in the wardroom (officers’ mess) is a hurried affair, and as we go on deck we see that the Nelson is already under way, in charge of dockyard tugs. It is a tricky business to manoeuvre these giant vessels through the narrow fairway of Portsmouth Harbour, with its strong tide-

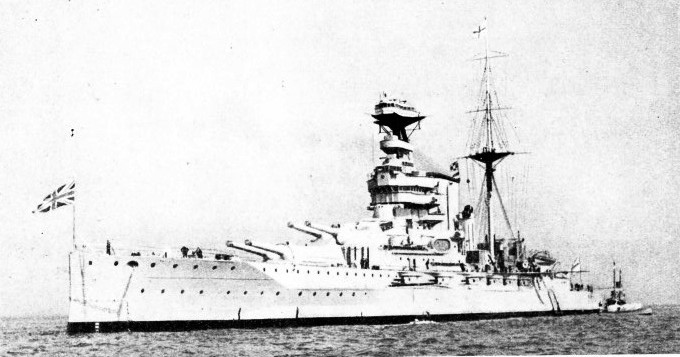

LAID DOWN IN 1912. H.M.S. Queen Elizabeth, the first of a class of battleships of that name. This ship was completed in 1915 and has since become one of the most famous vessels in the Royal Navy. After the war of 1914-

A few hours later, when we are well out in the Channel, steaming at a steady twelve knots -

Sharp words of command come from the bridge; the ship trembles as the helm is put over, and looking astern we see our hitherto straight wake transformed into a graceful arc. We are turning sharply to starboard -

A Direct Hit

It looks as though we are clear of the trap, and so we are, but our next astern, a big cruiser, is not so fortunate. Having successfully dodged two “tin fish”, she is just straightening out when another of those sinister white tracks is seen to be making straight for her. There is no time for the helm to act, and a few seconds later those on the cruiser’s deck feel the bump and jar which means that the dummy-

As it is, we look astern and see a conning tower rise from the sea, followed by the dark, glistening hull of a submarine. Men appear on her deck, and from the conning-

The day has turned out gloriously fine, though a stiff breeze is blowing from the north-

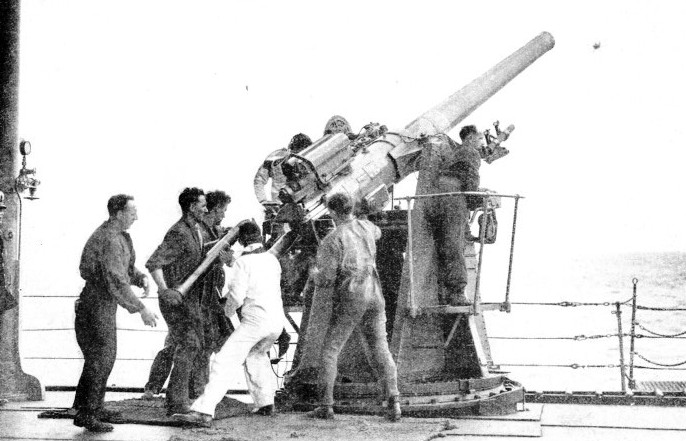

ANTI-

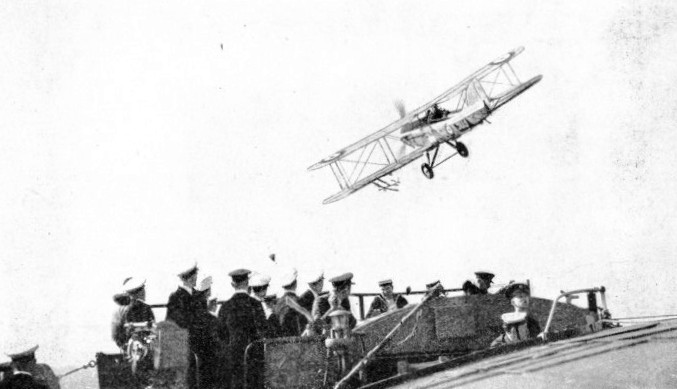

Accompanied by his observer -

A flat wooden target in the shape of a ship, but of no great size, is dropped into the sea to be towed astern of us at the end of a long cable. Meanwhile the crews of the four four-

By now the seaplane has reached a great height, so great, indeed, that it seems impossible to drop bombs with any degree of accuracy. But let us wait and see. Suddenly there is a whistling sound, and a small practice bomb strikes the water with a vicious smack and gives out a puff of white smoke. It has fallen some distance from the target, but the next bomb is much nearer. This is followed by a salvo of three which “straddle” the mark, two splashing to the right and the third to the left. Evidently the observer officer who is working the bomb trap in the seaplane is an expert at the work; he may also be using a particularly efficient form of bomb-

Attacked from Above

By now our anti-

Now the exercise is over. The seaplane descends, and as the battleship, with her screws going astern, loses way, the pilot makes a perfect landing alongside. Five minutes later our electric crane is hoisting the machine inboard on to its catapult and we are under way again, putting on speed to catch up with the rest of the squadron which has drawn ahead. In war conditions a big ship would probably not stop to recover its seaplane for fear of being torpedoed by a lurking submarine. The seaplane would therefore have to make for the nearest shore base or be picked up by some other, less valuable, vessel. It is probable that in war certain auxiliary ships would be assigned to the duty of salving aircraft flown from warships other than aircraft-

LEAVING THEIR FLOATING BASE. Aeroplanes taking off from H.M.S. Furious for exercise. This photograph was taken on board the aircraft carrier during a spring cruise to the Canary Islands. The carrier was accompanied by H.M.S. Rodney and H.M.S. Sturdy. The aeroplanes when not in operation are kept below the take-

As the cruise proceeds the Fleet carries out tactical exercises in obedience to signals from the flagship. The cruisers are ordered to scout ahead in search of an imaginary enemy. The battle squadron changes from line ahead to line abreast, and then forms a line of bearing. These various movements, unexciting in themselves, call for skilled navigation and seamanship. The smallest error of judgment may lead to a collision between two battleships, each carrying 1,200 men and worth millions of pounds. The destroyers are told off to make an anti-

Gunnery plays a big part in the training programme, but the fascinating story of how the modern Navy shoots must be reserved for a later chapter. Even while the Fleet is engaged in a “P.Z.” (tactical) exercise, the individual ships are constantly performing one or other of the score of drills laid down in the training manual. In one ship a third of the crew are told to become “casualties”, certain guns and controls are deemed to be “out of action”; then “heavy waterline damage”, “so and so many compartments flooded”, and “fierce fires raging on stokers’ mess deck” are reported. When such orders are given the routine must be instantly changed to what it would become if the ship really were half-

On another occasion a battleship may be ordered to take in tow a consort which has been “disabled”. This is a long and difficult operation even in fine weather, and one in which practically the entire crew of each ship has to take part. “Out paravanes” is yet another signal often made when ships are at sea.

The paravane is an ingenious apparatus for sweeping up submarine mines and rendering them harmless. In appearance it resembles a short, squat torpedo, fitted with large fins, and also with serrated steel jaws which cut through the mine’s stout mooring cable as if it were packthread. When the order is given the two paravanes are placed on trollies and rushed to the forecastle, there to be triced up on davits at either side in readiness for dropping. Once in the water they dive to and remain at a depth of many feet, while the action of the fins causes them to stream out away from the ship. If the taut paravane wire makes contact with a mine the mine’s cable is deflected into the toothed jaws and instantly severed. The released mine then bobs up to the surface and, being visible, is no longer to be greatly feared, even if it is not forthwith sunk by gunfire.

IN HEAVY SEAS. A remarkable view of H.M. destroyer Sturdy during manoeuvres is shown on the opposite page. This vessel of 905 tons, with an overall length of 276 feet, is now without armament and is used as a tender to the aircraft carrier Furious. Propelled by geared turbines, she has a designed s.h.p. of 27,000, and a speed of 36 knots.

Thus proceeds the strenuous sea training by which the Navy keeps itself fit and ready to meet any crisis. A brief description may now be given of the daily routine on board each big ship. The “hands” are called at 5.30 a.m. and have half an hour for dressing, washing and drinking their cocoa ration. From 6 a.m. to 7 a.m. decks are scrubbed and swept, after which breakfast is “piped”. At 8 a.m. (9 a.m. in winter) the colours are hoisted with impressive ceremonial. A few minutes before the hour signalmen bend the White Ensign to the halyards of the ensign staff, while others go forward in readiness to hoist the Jack Marine bandsmen have already mustered on the quarter-

Just after 9 a.m. the ship’s company musters on deck by divisions for inspection. This is followed by a brief religious service of prayer and hymns. For the next three hours all hands are hard at work above or below deck. The boys and young seamen undergo instruction in the schoolroom. Dinner at noon is preceded by the famous ritual of grog-

At 1.15 p.m. “out pipes” is sounded and the afternoon’s work begins. By teatime -

From 4 p.m. to 8 p.m. (the first and second dog watches) is the bluejacket’s favourite period of the day. True, he has work still to do, but in those hours a general air of tranquillity settles on the ship, and time passes quickly till supper is served at seven o’clock. Two hours later the Commander makes his rounds to see that everything is in order for the night, then visits the Captain to report “All correct, sir”. At ten o’clock comes the order to “pipe down”; hammocks are slung, and hundreds of healthily tired men turn in, some to fall asleep at once, others to enjoy a brief spell of reading in bed.

Ceaseless Vigilance

Although the greater part of the ship’s company is asleep, the ship herself is by no means at rest. All through the night watches are set and relieved, whether at sea or in harbour. Every few hours a small party of men, carrying safety lamps, descends into the powder magazines and shell rooms to examine the thermometers installed there. For when hundreds of tons of powerful explosives are stored in a confined space it is necessary to maintain a constant temperature. Were this allowed to vary there would be danger of decomposition or of other chemical changes which might end in spontaneous ignition and overwhelming disaster.

The routine here described is that of most weekdays. There are, however, welcome variations. On Saturdays only the most necessary work of the ship is done after the midday meal. The afternoon is consecrated to “make and mend”, when, in the original meaning of the phrase, the bluejackets overhaul their wardrobe. Except to the ship’s tailors, however, and the amateur practitioners of needle and sewing-

In small ships, such as destroyers, gunboats and sloops, discipline is less formal than in battleships and cruisers, and ceremonial is not so much in evidence. For this reason the average officer or rating frequently welcomes a transfer from a big ship to a little one, despite the lower standard of comfort which he is likely to find there.

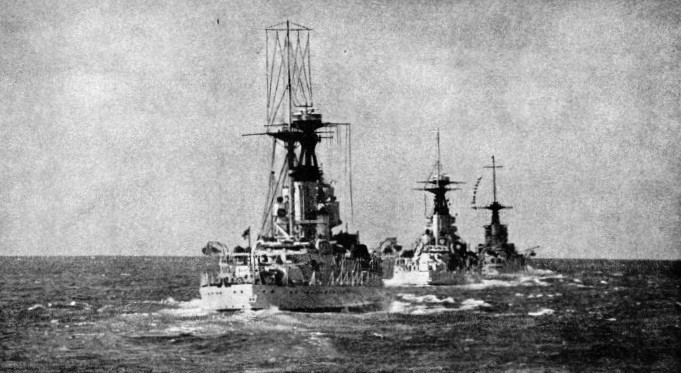

THE FIRST BATTLE SQUADRON performing tactical exercises. The Fleet when cruising at sea carries out tactical exercises in obedience to signals from the flagship. The various movements ordered call for skilled navigation and seamanship. While the Fleet is engaged in such exercises the crews of individual ships are going through special drills, and carrying out the duties that a naval action would necessitate.

You can read more on “Battleships and Cruisers”, “Floating Aerodromes” and “In the Royal Navy” on this website.