Time lost through laid-up or delayed shipping is one of the most serious problems that port and shipping authorities must face. Fog and ice are chiefly responsible for any such delay. This chapter describes the work of the vessels that free ice-bound trade routes

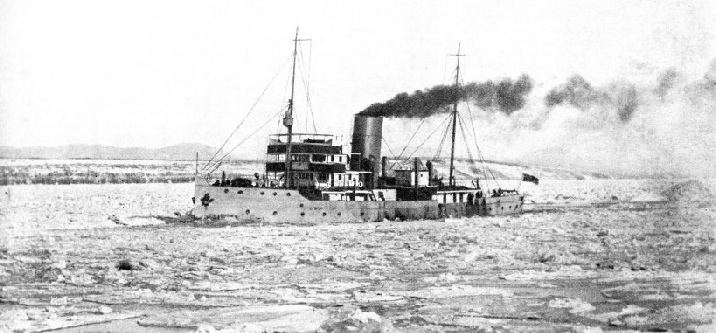

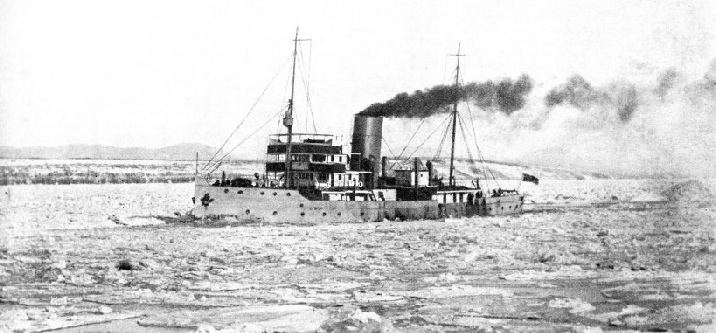

FREEING THE ST. LAWRENCE from ice. The Canadian Government ice-breaker Samuel, one of the latest types of ice-breakers, which keeps the St. Lawrence River free of ice-jams from Quebec to the open sea during the winter months. The Samuel can force her way through ice 28 feet thick.

OF all the strange ships which specialization brought into being, none is stranger than the ice-breaker. Designed to deal with conditions where sea-ice may be anything up to thirty or forty feet thick, it is an outstanding example of what engineering skill can do. Although the true ice-breaker did not begin to take shape until the middle of the nineteenth century, it had existed in a crude form for a long time before that.

Most of the old whalers were icebreakers of a sort. They were designed with immense hull strength to withstand the pressure of the ice in which they were constantly caught during their operations. Their wooden bows were sheathed with iron and their hulls given such lines that they had a limited ability to ride over ice and crush it with their weight or crumble it as they rolled. As far back as 1841 a Danish inventor named Hiorth claimed to have invented an ice-cutting steamboat which would plough its way through the thickest ice at a speed nearly as great as it could attain in open water. His invention never came to a practical test, and it is doubtful if any scheme for cutting ice could ever be effective.

The first recognized ice-breaker was the tug Pilot of Cronstadt. In 1870 she was given a new bow to permit her to crush the ice. In the following year, from the experience gained with the little Pilot, the Eisbrecher I was built for the Russians. After that there was a lull until 1883, although a number of small steamers were used to a certain extent. In that year Burmeister and Wain of Copenhagen, a firm that later became famous for the building of ice-breakers, built the Staerkodder of 553 tons and 800 i.h.p., the first of many icebreakers under the Danish flag.

Five years later the Fairfield Yard built the Stanley for the Canadian Government, a vessel of 914 tons gross, designed to maintain the mail service between Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland, and to break herself a passage through the ice. In the same year the first of the ice-breaking train ferries on the Great Lakes was built. She was the wooden St. Iqnace, sheathed in iron on the waterline and having a gross tonnage of 1,476. In 1889, the veteran Pilot was replaced by two small icebreakers, Zarja and the Luna. They were really tugs and made no effort in the depths of winter to keep the waterway open to Cronstadt and St. Petersburg, as Leningrad was then called.

These little vessels, small as they were and limited in ability, showed the Northern countries what could be done. In the ’nineties quite a number of such ships were built, the majority of them by the various port authorities. In 1894 there was the Bore, 391 tons, for work at Malmo, and the Isbjorn for Christiana, where she contrived to keep the channel free in practically all ice conditions.

These little vessels, small as they were and limited in ability, showed the Northern countries what could be done. In the ’nineties quite a number of such ships were built, the majority of them by the various port authorities. In 1894 there was the Bore, 391 tons, for work at Malmo, and the Isbjorn for Christiana, where she contrived to keep the channel free in practically all ice conditions.

AT THE ENTRANCE TO THE ZUIDER ZEE. Dutch ice-breaker at work on the River Ijsel, which drains into the Ijsel Meer, most important undrained portion of the Zuider Zee, to clear the way for traffic between Amsterdam and Kampen. Dutch engineers have designed a number of efficient vessels which can combine ice-breaking with towing and salvage work.

In that decade the Russians were greatly increasing their overseas shipping and were also extending their Empire towards the East. Both plans demanded ice-breakers. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., the Tyneside shipbuilders, saw an opportunity in the demand and began to specialize in the design and construction of ice-breakers.

This specialization soon found appreciation in Russia, where the biggest and best ice-breakers were wanted and where port authorities were willing and able to pay for them. Most Northern countries were building quite small vessels that were capable only of improving harbour conditions to a useful extent. But the Russian authorities began to order ships of a standard never before attempted. The ships built during the period were noteworthy and received their share of attention.

The Baikal was built to connect the Eastern and Western sections of the Trans-Siberian Railway across the fifty-two miles of Lake Baikal. She was a train ferry, but as there was a period before and after the winter when the lake was covered with ice not strong enough to support the railway and its traffic, she was also fitted as an icebreaker. She was built on the Tyne, every piece marked, taken down and shipped to Siberia. Her structure weighed 2,700 tons, and it was packed in 6,900 packages to be taken 1,500 miles across Siberia and re-erected on the shores of the lake. The boilers were the greatest problem, for no package could weigh more than twenty tons. The difficulty was overcome by fitting her with fifteen small boilers. Each of these was dragged with sledges by hand and pony, from the end of the railway to the slip where she was being built. She did magnificent work until the line was completed round the southern end of the lake during the war with Japan.

For harbour purposes, and especially to prevent the Navy being frozen in for a large part of the year, the Russian Government had a number of fine breakers built. The most outstanding of them was the Ermack of 1898. She was intended to keep the Baltic ports open through the winter and was the biggest ice-breaker ever built. Her dimensions were 370 feet by 71 feet, and with a load draught of 25 feet she had a displacement of about 8,000 tons, the greater part of which could be used for smashing ice. As she was originally built, designed by Russians and Tyne-siders in collaboration, she had four sets of engines, working three screws aft and one forward. The purpose of the forward screw was to agitate the water under the ice and thus leave it unsupported when the curved bow of the ship was forced over it. Due precautions were taken to protect the forward screw from damage, but it was found to be not really worth while and was discarded.

This alteration was carried out by the original builders, and at the same time she was given a new bow of improved form that enabled her to tackle ice 12 or 13 feet in thickness as a regular routine job. On one occasion she successfully smashed ice 34 feet thick. Her hull was so designed that she could be driven on to the ice to use her weight. In addition its form was such that if the ice closed in on her she was lifted clear, and again her weight came into operation. Provided with very heavy frames spaced a foot apart and 25 feet in height on either side, with plating flush and over an inch in thickness, the hull internally was divided into forty-eight water-tight compartments by strong bulkheads. She was the first ice-breaker to be designed as a cargo and passenger boat. She was sent out in the winter and put to a thorough test, forcing a lane right through the Gulf of Finland to Cronstadt, escorted by a regiment of infantry on skis, and saving eleven ships on the way. Several of them had been written off as lost.

When she tackled 34 feet of polar ice in the extreme North her speed had to be cut down to about three knots, because of the difficulty of controlling her with such severe shocks, but 24 feet of solid ice, covered by a foot or two of snow, was charged at nine knots with complete success. In one season she rescued frozen-up shipping valued at over £2,000,000. On another occasion she salved the Russian battleship General Admiral Graf Apraxim, which would certainly have been crushed. While they had the Ermack in the Baltic the Russian naval authorities felt that the fleet could always get out into the open sea and need no longer be forced to winter at Cronstadt, although it generally continued so to do.

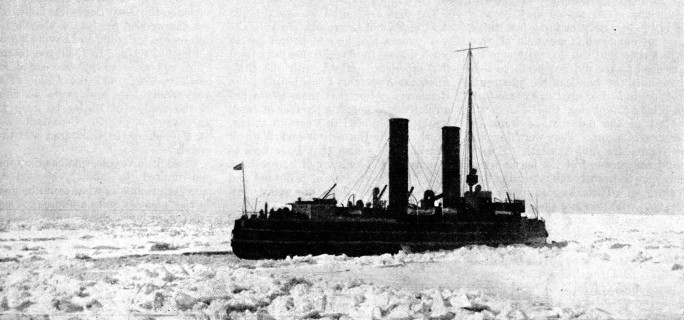

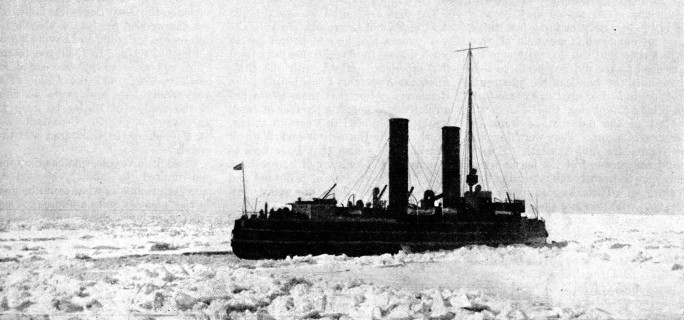

STRATEGIC REASONS were partly responsible for the construction of the Ermack for the Russian Government in 1893. She was 370 feet long, 71 feet wide, with a load draught of 25 feet, and had a displacement of about 8,000 tons, and was the biggest ice-breaker ever built. While they had the Ermack in the Baltic the Russian naval authorities felt that the fleet could if necessary always reach the open sea. The Ermack could charge 24 feet of solid ice at nine knots with complete success. In one season she freed frozen-up shipping valued at over £2,000,000).

The striking success of the Ermack produced other ice-breaker orders for Armstrong Whitworth’s; one of the first was the Sampo, of 1,339 tons, built to keep open the commercial ports on the Gulf of Finland, especially Helsingfors. Such ships as the Sampo and the Ermack were naturally very expensive to maintain, and it was always a question of balancing their costs against increased buisness.

Prompted by the success of these ships the Canadian Government had built for it at Dundee in 1899 the ice-breaker Minto of 1,090 tons. She was followed by the 1,461-ton Scotia, intended for the inter-Colonial Railway of Canada between Cape Breton Island and Nova Scotia, across the Strait of Canso. She was a double-ended ship with three sets of rails on deck and was the first vessel in which the machinery was controlled from the bridge. The ice-breaker Montcalm, 1,432 tons, built in 1904, was the next ship built and was intended for service on the St. Lawrence. The Lady Grey, of 1,080 tons, followed in 1906. In 1913 certain patriotic interests in Russia, encouraged by the power of the Ermack, determined to try to open up the North-East Passage across the top of Siberia for commercial purposes. Ice-breakers were used for the preliminary survey work. It was impossible to push the plan at full strength during the war of 1914-18, but in 1914 and 1915 the ice-breakers Tamyr and the Vaigalch contrived to make the passage. The former got through in one season, but the Vaigatch had to take two, spending one winter in the ice. In the meantime the Russian Navy greatly augmented its ice-breaking facilities in order to keep as many ports as possible open for the importation of munitions.

The very serious position in which some of the combatants found themselves for food and commercial necessities at the end of the war of 1914-18 forced increased attention to icebreakers. In 1920 the Soviet Government attempted to revive a full icebreaker service, but was defeated by the condition of neglect into which the material had fallen during the revolution. It was realized that an ice-breaking service was more necessary than it had been before 1914, and the authorities determined to provide it. After the 1914-18 period other Northern nations had improved their ice-breaking service. In Germany old battleships retained under the Treaty of Versailles were repeatedly used for opening channels to icebound merchantmen; Dutch and Danish engineers evolved a number of very efficient little vessels that combined ice-breaking in port and on the inland waterways with towing and salvage work.

The new Baltic Republics were very enterprising. Latvia went, to Beardmores on the Clyde for the 1,932-ton Krisjanis Valdemars. In her first season she brought 178 ships through the ice. Finland obtained from Smits of Rotterdam the 2,622-ton Jaakarku. Smits were the first Dutch shipbuilders to venture on an ice-breaking contract, and they revived, with considerable success, the Ermack’s original scheme of having a forward propeller to undermine the ice. The Jaakarku is now an efficient unit of the Finnish Navy, being armed with six- and three-inch guns. The Atle, 2,600 tons displacement, with a speed of sixteen knots, was built for the Swedish Navy in 1926, and was their first; in the following year the U.S. Coastguard had the diesel-electric cutter Northland designed as an ice-breaker for miscellaneous service in Alaskan waters and within the Arctic Circle and in the Pacific.

SO SUCCESSFUL WAS THE ERMACK in 1898 that many other ice-breakers were built, including the Minto for the Canadian Government. She was built at Dundee in 1899 and had a tonnage of 1,090.

As its contribution to the Polar Year of 1932 the Soviet Government contributed the ice-breaker Alexander Sibiriakov. She made the North-East Passage from Archangel to Vladivostok in one season and was able to transport cargo in addition to smashing a passage for herself and carrying out a number of valuable scientific observations. She was built in 1909 on the Clyde as the Bellaventure of 1,384 tons gross, and although far from ideal her success revived all the pre-war enthusiasm of the Russia Government for the North-East Passage as a commercial highway.

In this enthusiasm the Soviet Government built the steamer Chilyuskin in 1933, at Burmeister and Wain’s yard at Copenhagen. A ship of 4,500 tons, she sacrificed many of the ice-breaker’s qualities to cargo capacity, but was much more than merely a cargo steamer with ice-breaking ability. Her purpose was to test the North-East Passage as a commercial waterway by way of Leningrad, via the Murmansk, to Vladivostok, but not far from Wrangel Island she was trapped in the ice and sank.

In succeeding years the North-East Passage, with the assistance of icebreakers, became easier and easier, and the annual expedition to the Kara Sea in the North of Siberia is regarded as an ordinary trip.

The Russian Government planned to increase its ice-breaker fleet, and in 1935 ordered six vessels to be built in Soviet

yards. Four of them are steamers, two are driven by diesel electric power, and some, at least, of them are to be fitted to carry aeroplanes (to assist in surveying work) and all the scientific equipment necessary for the researches to be carried out before the North-East Passage can become really practical.

Among many ships, one of the most interesting was the Ymer, built at the Kockum Shipyard at Malmo in 1932 for the Swedish Government. After a good deal of discussion and criticism the authorities decided to follow the example of the U.S. Coastguard with the Northland and give her diesel-electric machinery of 9,000 b.h.p. On dimensions 258 feet overall by 63 feet by 21 feet loaded draught, she had a displacement of 4,300 tons. She was given the very latest type of ice-breaker hull, and for trimming the ship by the head or stern as might be necessary, and for making her roll when a lateral motion was desirable to break up ice alongside, a very elaborate pumping system was included with numerous pipe lines to the various tanks. Each of the heeling tanks on the side of the ship has a capacity of 200 tons and a single main pump capable of moving this amount of water from side to side in ninety seconds. So that she might be able to tow the ships for which she was making a path she was equipped with a big towing engine aft.

The choice of diesel-electric machinery added nearly £20,000 to the cost, but it was considered to be justified. Like the Ermack, the Ymer has a bow propeller; aft are twin screws instead of the three of the famous pioneer. The propeller shafts were comparatively short, with a huge electric motor at the end of each supplied by diesel-driven generators. Six generating units were selected as the most economical system, the current output being varied by the number of diesels kept running: the employment of a group of small units reduced the risk of breakdown. Two diesel generators are sufficient to give a speed of about 12¾ knots, while full speed of nearly 15 knots demands all six.

The Ymer which cost £221,000 to build, carries a seaplane under a derrick between the funnel and the mainmast.

The Ymer which cost £221,000 to build, carries a seaplane under a derrick between the funnel and the mainmast.

ICE-BREAKERS AT WORK on the River Elbe in Germany. So serious did the food problem become at the end of the war of 1914-18 that many countries were forced to improve their ice-breaking service for winter supplies. In Germany old battleships retained under the Treaty of Versailles were often used for opening up ice-bound channels for merchant ships.

According to Lloyd’s Calendar, two winter seasons are seldom alike. Several places have been blocked during one winter and quite open the next.

Nearly all the Black Sea ports are free of ice all the year round. Kherson is an exception, and to a certain extent so is Nicolaieff, which is icebound only for a short period. Nicolaiefi is an example of the vagaries of ice-blocking. It is not ice bound every year: in 1929 there was no ice at all. Ice-breakers are provided during the winter season.

Navigation by steam vessels in the North Sea is rarely hindered. The mouth of the Eider, however, is closed to sailing vessels for about ten days during the winter. In the Elbe conditions vary. Ice generally appears in December and at irregular intervals may interfere with navigation until the end of February. Ice has been known to appear in November and to last until March. Ice-breakers, however, break up the ice and keep it in a floating condition. The Elbe is never completely closed by ice below Gluckstadt, but above that port it is closed at intervals.

You can read more on “The Chelyuskin Rescue”, “The Lake Baikal” and

“The North Atlantic Ice Peril” on this website.

These little vessels, small as they were and limited in ability, showed the Northern countries what could be done. In the ’nineties quite a number of such ships were built, the majority of them by the various port authorities. In 1894 there was the Bore, 391 tons, for work at Malmo, and the Isbjorn for Christiana, where she contrived to keep the channel free in practically all ice conditions.

These little vessels, small as they were and limited in ability, showed the Northern countries what could be done. In the ’nineties quite a number of such ships were built, the majority of them by the various port authorities. In 1894 there was the Bore, 391 tons, for work at Malmo, and the Isbjorn for Christiana, where she contrived to keep the channel free in practically all ice conditions.

The Ymer which cost £221,000 to build, carries a seaplane under a derrick between the funnel and the mainmast.

The Ymer which cost £221,000 to build, carries a seaplane under a derrick between the funnel and the mainmast.