© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

In the Mercantile Marine

Mechanization and steam have not lessened the romance of a career at sea. Courage, endurance and resourcefulness are still called for, and the sea retains its appeal to youth

GOING TO SEA - 1

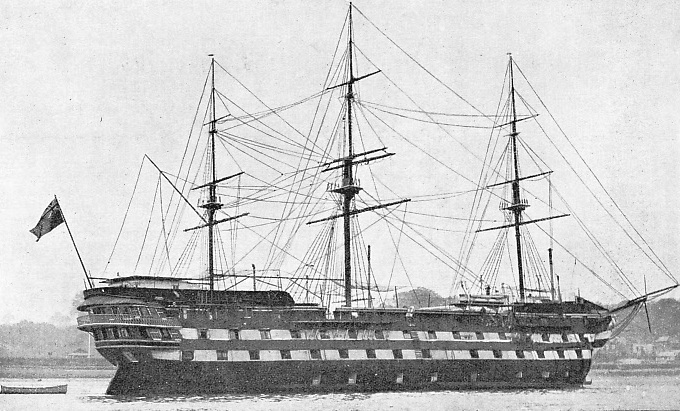

FORMERLY A WARSHIP of the early wood and steam type, the Worcester, moored in the Thames near Greenhithe, Kent, is now a training ship for boys who intend to become officers in the Mercantile Marine. Cadets enter between the ages of twelve and sixteen, live on board and have their playing-

NEARLY every healthy boy has a desire to go to sea at some period of his youth, and many contrive to gratify their demand when they grow up. Unfortunately, only a small proportion do so well out of a sailor’s life that they stay at sea, and numbers are disappointed because they start in the wrong way. It is still possible to go to sea in the manner which was practically the only one for centuries; to find a ship about to sail, and by some means to persuade the captain to include the raw lad in his crew without experience or previous preparation. But, it handicaps the lad badly from the first, and is seldom successful.

Under the bad old method, the boy is left to pick up the sailor’s craft as well he can; a craft so complex that careful training is really necessary. It is nobody’s business to teach a boy on shipboard, and his early experience is that of being a hindrance. Perhaps a kindly seaman or officer will go out of his way to give some elementary training at his own personal sacrifice, but the “green” boy at sea must expect discouragement and often hardship, although the days when everything was taught with the rope’s end are happily over.

Many opportunities exist in Britain, however, by which the lad anxious to go to sea can start with a sound foundation; and, having started, every sailor has a chance to obtain a master’s certificate. A training in the forecastle is no bar, although, naturally, it is a more difficult path than through apprenticeship. Opportunities are provided in training ships moored in ports and rivers and in establishments ashore; and generally the Board of Trade allows half the time spent in them to be counted as time at sea for qualification purposes -

If possible, an establishment should be chosen, either ashore or afloat, which is within convenient reach of the boy’s home, and which is most likely to assist him in his career. This is an important point, for there are few establishments which afford training of a completely general character. Specialization is the rule.

The senior training establishment in the country is the Warspite, off Grays on the Thames, the present ship being the eighth which has carried on the good work. The training ship movement was started by the Marine Society in 1756 when, at a time of great national distress, numbers of poor boys, for no greater offence than being homeless, were gaoled and made criminals by the process. Certain charitable persons, headed by Mr. Hanway, the inventor of the umbrella, set themselves the task of saving these boys and passing them into the Navy or the Merchant Service, both of which badly needed them.

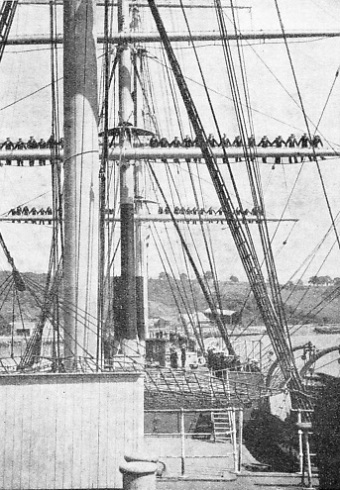

OVER 12,000 BOYS have been prepared for life in either the Royal Navy or in the Merchant Service on board the new and old Arethusa. This vessel is connected with the Shaftesbury Homes and lies on the Medway, near Rochester, Kent. The training ship movement was initiated by the Marine Society in 1756.

Their initial aim was no more than to provide the boy with decent kit instead of letting him go to sea on an indefinite commission with no more than the clothes on his back. This made far more difference than can be imagined to-

Closely associated with her is the Arethusa, connected with the Shaftesbury Homes, which takes the poorest boys of good character and gives them opportunities which are seldom wasted. For many years the old frigate Arethusa, the last British man-

At Liverpool the Indefatigable provides a two-

Originally an old frigate was loaned by the Admiralty in 1864, and was replaced in 1913 by the purchase of the present vessel (ex-

The maximum fee asked is £35 per annum, but reductions are made in circumstances where parents cannot afford this sum. In some instances the orphans of seamen are admitted without payment. Something like twenty-

There were formerly many other training ships round the coast, some of which have been discontinued; others have been transferred to quarters ashore as the supply of suitable ships declined.

School of Seamanship

The Wellesley Nautical School still retains the name of the “wooden walls” in which it was housed for years on the Tyne, although she was burned during the 1914-

IN THE MERCANTILE MARINE

Distinctions of rank as recommended by the Board of Trade. These distinctions are not strictly followed by all the shipping companies.

The numbers indicate:

(1) Certificated Master. (2) Certificated Chief Officer. (3) Certificated Second Officer. (4) Certificated Third and Junior Certificated Officers. (5) Uncertificated Junior Officer. (6) Second Master. (7) First Officer. (8) Junior Second Officer. (9) Certificated Chief Engineer. (10) Certificated Second Engineer, and Chief Refrigerating Engineer. (11) Certificated Third Engineer and Second Refrigerating Engineer. (12) Certificated Fourth and Junior Engineers. (13) Uncertificated Junior Engineers, Refrigerating Engineers, Boilermakers and Electricians. (14) Second Chief Engineer. (15) Junior Second Engineer. (16) Junior Third Engineer. (17) Junior Fourth Engineer, (18) Ship Surgeon. (19) Assistant Ship Surgeon. (20) Senior Purser, where three or more are carried. (21) Purser. (22) Assistant Purser. (23) First Wireless Operator. (24) Second, Wireless Operator. (25) Third Wireless Operator. (26) Cadets or Apprentices. (27) Chief Steward on Passenger Vessels. (28) Assistant Chief Steward. (29) Steward. (30) Assistant Steward. (31) Steward on Cargo Vessels. (32) Boatswain. (33) Boatswain’s Mate. (34) Quartermaster. (35) Quartermaster’s Mate, (36) Cook. (37) Standard Cap Badge for Officers. (38) Peak of Master’s Cap. (39) Peak of Cap for all other Officers. (40) Petty Officers’ Cap Badge. (41) Mercantile Marine Coat Button.

The National Nautical School at Portishead on the Bristol Channel was established in the hulk Formidable in 1869, and moved ashore in 1906; while the Prince of Wales’s Sea Training Hostel at Limehouse is maintained by the British Sailors’ Society. That society first interested itself in the training of boys in 1831, using the vestry of Stepney Church, and started the hostel during the war to train the orphan sons of seamen, and, later, boys whose parents make a contribution towards the cost of training. The majority are drawn from the B.S.S. Cadet Corps.

There are other establishments round the coast which help with the good work. Among them is the Scarborough Sea Training School, which, taking boys from twelve onwards, has a sailing tender, Maisie Graham, for summer cruises in the North Sea, a 100-

The boy with salt in his blood still has ample opportunity of obtaining good grounding in his profession and beginning his career with big advantages. But, having made certain that his desire for a sea life is not a passing whim, his parents must satisfy themselves, to avoid later disappointment, that he is physically fit to be a sailor and, most important of all, that he is able to pass the Board of Trade eyesight tests, which can be undergone for a few shillings.

A feature of the British Merchant Service is that no lad who enters it in any capacity need sacrifice his ambition. The highest ranks are open to the forecastle boy, and a large number become master mariners, some of them in command of important liners.

Methods of Entry

In the old days of sail it was general to “go aft through the hawse-

Apart from this laborious path through the forecastle, there are two ways of becoming an officer. The first is through a training ship or establishment on shore; followed by sea experience. The second is by direct entry into a company from school, either as a cadet or as an apprentice. The principal training establishments are the Worcester, on the Thames, the Conway, on the Mersey, and Pangbourne Nautical College, on the Berkshire bank of the Thames. All three establishments aim at finishing a boy’s general education with a view towards his future career, in addition to giving him a thorough theoretical grounding in maritime matters. Boys can enter the Worcester between twelve and sixteen, Pangbourne between thirteen and fifteen, and the Conway between thirteen and seventeen; and in each instance they get a good training; so good is it that parents send their boys to these establishments without any intention of their “going to sea” for a livelihood. The Board of Trade appreciates the technical side of their education, and allows two years in one of these establishments to count as one at sea, the actual apprenticeship thus being reduced to three years.

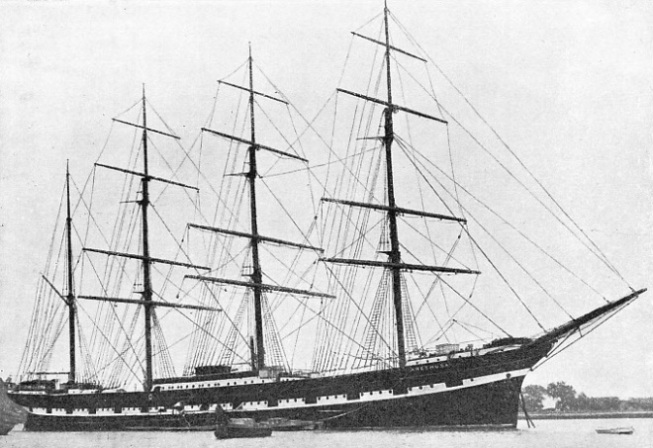

PUT INTO SERVICE IN 1933 as a training ship, the Arethusa, a four-

There is considerable discussion as to which is the better means of training. In the Worcester and the Conway the lads live on board one of the old “wooden walls”, sleeping in hammocks alongside a busy commercial waterway where they can study every type of ship. Their playing-

Parents of smaller means have the training ship Mercury in the River Hamble, near Southampton, in charge of Commander C. B. Fry, the famous sportsman, where boys of from twelve to fifteen and a half are taken for preliminary training. These establishments send a number of their lads to the Navy, but the Merchant Service is their first consideration.

The authorities recognize that only a theoretical grounding can be found in a training ship, and boys who distinguish themselves, and leave with the honour of cadet captain, have to make the same start as a cadet or apprentice, as those coming direct from school. The terms “cadet” and “apprentice” are largely interchangeable, but often the latter applies to one training in a ship engaged in trading, while the former lad is in a special training ship,with proper facilities for instruction, which are maintained by one or two of the first-

Cadet ships are generally cargo liners running on normal service, but having special accommodation for from thirty to sixty cadets, an instructional staff in addition to the ship’s officers, and extra stewards to look after them. They are not left to pick up knowledge as they go along. Although they do much of the work of the ship, everything is explained to them; in addition, they have time to attend classes on theoretical subjects. Having put in the necessary “sea time” and being ready to sit for their second mate’s certificate, it is not necessary for them to attend a crammer ashore for a grounding in the mathematical side of their profession.

The disadvantage quoted against the cadet-

A SAILING LESSON ON THE THAMES. Cadets from the Nautical College at Pangbourne, on the upper reaches of the Thames, receiving instruction in the art of sailing. Boys entering this college between the ages of thirteen and fifteen are trained to be officers in the Mercantile Marine. Arrangements are also made for the cadets to join the Royal Naval Reserve, and cadetships for the Royal Navy can be won. The period of training at Pangbourne lasts two years.

Until a few years before the war, the normal apprenticeship was in a sailing vessel. The regulations insisted that “time” should be spent in sail, but in the majority of instances the lad did not “leave the sea and go into steam” until he had obtained some of his certificates, and often not until he was a fully qualified master mariner. That way is now impossible in the British merchant service, as we no longer have any deep-

The old sailing-

The path to the command of a liner is not a smooth one; the degree of skill necessary to navigate a modern ship with safety demands a high standard of training and examination.

You can read more on “Going to Sea”, “Pilots and Their Work” and “The Work of Trinity House” on this website.