The Q-ships ceased their activities at the end of the war of 1914-18. But the deeds of the men who manned them have lived on to provide a record of courage and self-sacrifice that cannot be surpassed. The most famous Q-ship officer was Gordon Campbell, whose story is told below

MYSTERY SHIP ADVENTURES - 1

DECOY ships, disguised as cargo vessels and the like, and known as Q-ships, were evolved to fight the submarine menace in the war of 1914-1918. They provided that element of surprise which is the basis of successful naval warfare.

When it was suggested that decoys should be used against submarines, coasters or colliers had to be converted into cruisers of a special kind. Such a unit, externally, resembled thousands of other vessels normally seen crossing the North Sea any day of the week, or coming up the English and Irish Channels. She even flew the Red Ensign, and her crew wore no naval uniform, but were dressed in soft hats, caps and old clothes. The guns were kept hidden until the last second before the action, when up would go the White Ensign.

The officers and men serving in these unarmoured colliers, tramps, liners and cross-Channel packets were drawn from every category of the sea - Royal Navy (active and retired lists), Royal Naval Reserve, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, and Royal Fleet Reserve. They came from battleships and little ships, from fishing vessels, sailing craft, yachts, barracks, offices and cab-ranks. Hand-picked, disciplined (though many were real “hard cases”), they were every one volunteers for what could be nothing but weeks of boredom suddenly enlivened by the fiercest excitement, ending probably with death. For their captains the responsibilities were enormous. First-class seamanship, exceptional coolness, immense patience, considerable imagination and quite unusual initiative were demanded.

Consider the lonely position of a Q-skip captain who was so well disguised his ship and his intentions as to entice a U-boat till her commander thinks she has got a sitting-shot. The enemy becomes cautious, steams round the steamer at first out of range, then takes confidence and draws nearer - still on the surface. The Q-ship has been shelled a few times, and a bit of coloured bunting orders her to stop. She does so, blows off steam, pretends to abandon ship, and sends away in her boats (apparently) all her crew. But the captain, lying on his stomach behind the canvas dodger of the bridge, his eyes watching the submarine, his mouth resting on the voice pipe which leads down to the gunlayers, is still hoping the enemy will come muck nearer. At last, after an agony of suspense, the conning-tower seems to grow bigger and more distinct. The U-boat’s captain has steered among the boats and begun questioning the “panic-party”, whom he presently leaves. He is about to submerge before loosing off a torpedo, when the Q-ship captain sees through his canvas slit something more than the rolling seascape. This is the climax, the chance of a lifetime, the opportunity that may never come again. Think quickly he must, act rashly he must not; on his independent decision depends the very existence of ship and of his crew crouching behind the concealed guns. If the delay is too long, that torpedo will blow a hole in the engine-room and admit the rushing waves; if the decision is too soon, the submarine will take fright and dive, only to appear again at night and sink them unawares.

The ideal, imperturbable, “mystery ship” master was always one who could see into his rival’s mind and forestall his rival’s next step. Then at the fateful second - the “unforgiving minute” - down must fall the Red Ensign, up must go the White Ensign. Down come the bulwarks and false coverings, the guns do their job, and the enemy’s fate is settled definitely almost in a flash. No half measures. No bungling. No misfires. No misunderstanding. Plain, indubitable efficiency, complete and devastating.

That was how the Q-ships were run.

Let us go aboard one of these most ordinary-looking steamers. This one is just a three-masted, single-funnel, single-screw coaster, measuring fewer than 300 feet long, and drawing about 14 feet. Her displacement is not much more than 2,000 tons, and her speed with clean bottom only ten knots at the best. Her crew are berthed in the forecastle, the engineers’ mess and cabins are aft, and the captain and officers’ mess and cabins are near the bridge amidships. She has five guns, of which one is mounted on the after hatch, but disguised by a dummy ship’s boat that has been sawn in two and can be removed instantly. Other screens are specially hinged so that a mere touch will allow them to flap down and give free play to the guns. One long sounding of the alarm gong would send everyone to his station, the signalman being responsible for hoisting the White Ensign.

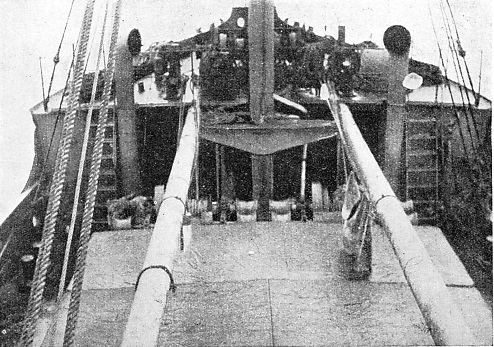

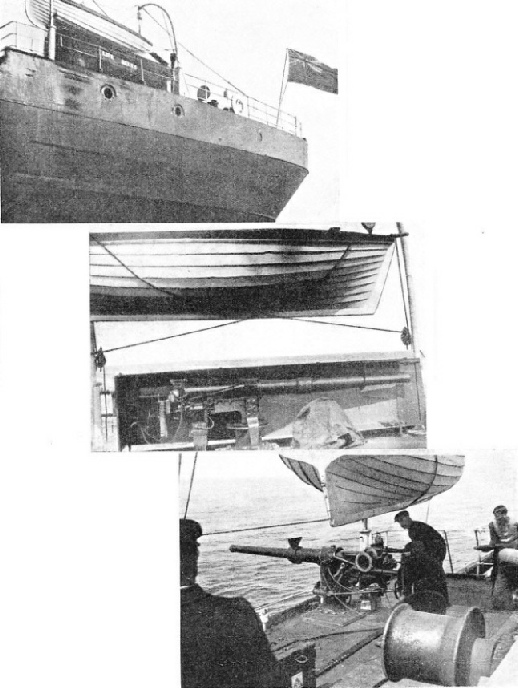

THE ARMAMENT of a Q-ship was all concealed except sometimes for one small gun - possibly a 2½-pounder - which latterly merchant vessels generally carried for their defence, and, therefore, added to the genuine appearance of the vessel. The first Q-ship was commissioned in November, 1914, the second in January, 1915. The Red Ensign can be seen at the foot of the ensign staff, the White Ensign having been run up to disclose the ship’s status to the enemy.

To mislead the U-boat captain, if he asked questions of the “panic party” rowing in the boats, these men were taught their daily lies, so as to repeat without hesitation the fictitious name of the ship, her alleged cargo, pretended destination and so on. If perchance a suspecting enemy had guessed the Q-ship’s true character (and this did happen sometimes when the Q-ship opened fire too soon), so that the U-boat hurriedly made away, then the immediate duty of the “mystery ship” was to get away likewise. Hoping for thick weather or fog, she made the best of the night hours, during which she completely altered her disguise. This was effected with incredible success by such methods as repainting funnels, putting thereon new distinctive markings (of another shipping company), repainting even the hull and the “boot-topping” of her water-line, taking down one of the three masts, filling in the well-deck forward, adding a false steam-pipe to the funnel, shortening derricks, altering cross-trees, varnishing the wood bridge-screen, adding or removing false deckhouses, and so on. I have myself been deceived more than once by a Q-ship that I well knew. On another occasion, when commanding a small steamer that was familiar to many of my naval friends, I was able to deceive them even in harbour and lying alongside. Merely by stepping a foremast, a liberal use of paint, a faked name on the bows and stern, and covering the gun with some odd articles, our associates were led to believe we had got a new ship.

It was off the south and west coasts of Ireland that the principal area for Q-ship operations developed. The plain reason was that submarines were bent on sinking every steamer and sailing ship coming across the Atlantic, or up the Bay of Biscay, bringing necessary supplies to such ports as Liverpool, Southampton, London and Avonmouth. Tramp steamers and colliers were armed and sent by the Admiralty to cruise off the Western Approaches. They came under the orders of Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, and were based on Queenstown (Cobh), but using also that out-of-the-way fjord known as Berehaven for a subsidiary base.

Among the first to arrive was the 3,207-tons Lodorer, which had been fitted out at Devonport and commissioned - most auspiciously - on Trafalgar Day of the year 1915. In all proceedings connected with these vessels the utmost secrecy was aimed at; and, since certain rumours had begun to spread concerning this Lodorer, she changed her name to Farnborough while on passage from Devonport to Queenstown. To her was appointed a young officer, Lieutenant Gordon Campbell, R.N., as captain.

The Farnborough had her first success only after six months of wearisome patrolling without so much as sighting a submarine. Campbell had told Admiral Bayly that he feared he would end the war without once firing a gun. To-day the Farnborough’s late skipper is a vice-admiral (retired), with a V.C. and two bars to his D.S.O. He will be remembered for all time as the greatest Q-ship captain who ever went out against U-boats. It was on March 22, 1916, that he encountered, enticed, fooled and destroyed U 68 off south-west Ireland, which won him promotion and his D.S.O. Less than a month later he was again in action, but a mistake robbed him of certain victory, and the enemy got away. For after the submarine had fired a shot, one of the Farnborough’s crew thought this was his own ship opening fire, so he fired also. Even the best organized “Mystery Ship” can have her chances spoiled.

But less than another year of rolling about the ocean brought a great reward. It was now February 17, 1917, and the area once more off south-west Ireland. The sea-strife had by this date become terribly keen. U-boat captains were being driven to sink more ships. They were carrying out their orders drastically. A favourite spot was some thirty or forty miles south-west of the Fastnet Lighthouse, off the coast of southwest Ireland. Hither also Commander Campbell now took his Farnborough. The orders which he issued to his officer-of-the-watch were drastic enough and show the determined courage - the reckless resolve - to perform duty even with utmost self-sacrifice. This is what he wrote down in the Order Book:

“Should an officer-of-the-watch see a torpedo coming, he is to increase or decrease speed as necessary to ensure it hitting.”

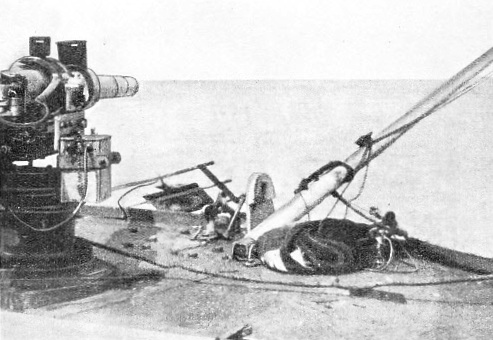

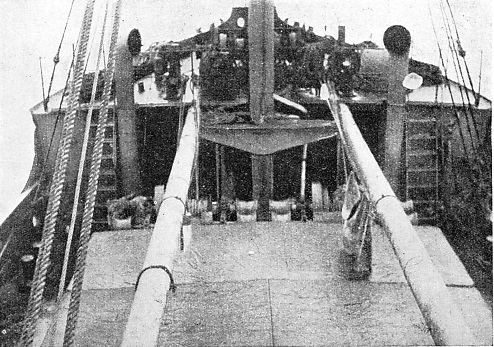

THE DECOY. The innocent-looking stern of a “mystery ship” flying the Red Ensign as a disguise. Beneath the lifeboat is a gun ingeniously hidden by what appears to be a life-belt locker. Below is an illustration showing how cleverly this concealment has been effected. Other screens are specially hinged so that they will flap down at a touch, and give free play to the guns.

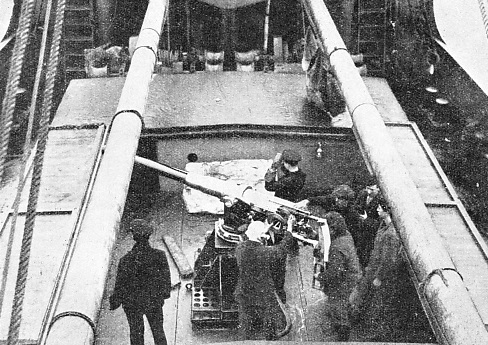

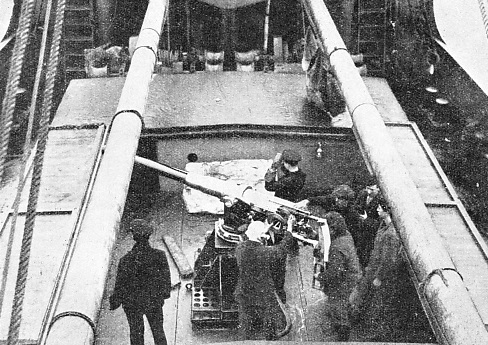

UNMASKED. The guns of the “mystery ship” would remain concealed behind bulwarks and false coverings until the last possible moment to ensure a direct hit on the submarine when she was at close quarters. The success of the engagement depended upon choosing the correct moment to clear for action. The picture below shows the gun uncovered and with the man on the right ready to insert a shell in the breech.

To obtain perfect understanding, this was read and signed by all of them. Every member of the Farnborough’s crew had been warned of what might be expected under this rule before sailing, and allowed the chance of quitting the ship. Of course they stayed - to a man. They knew their captain, and he knew his job. They knew that the enemy had become wary of Q-ships, and had resolved to clear them off the seas.

Thus at 9.45 am, while jogging along doing seven knots, the Farnborough saw a torpedo coming; but, instead of avoiding the missile, the steamer altered helm and was struck abreast of No. 3 hold, which caused a violent explosion and a great hole. Two lifeboats and one dinghy were lowered, and the “panic party” in them rowed about, while Commander Campbell lay hidden on the bridge watching his opportunity. “Engine-room filling”, came the report up the voice-pipe. “Hang on as long as possible”, went back the answer. Meanwhile the enemy could be seen 200 yards away, just submerged, but making a thorough examination of this doubtful ship through the periscope. Would she come any nearer? Was the time ripe for disclosing the Farnborough’s true identity? Or would the German fire another torpedo and blow them all to pieces?

Campbell waited and watched. The seconds ticked by. The stricken ship could not last much longer. The temptation to do something was resisted. Now the submarine approached till she was only thirteen yards away. Looking down from his lonely bridge, the captain could see the U-boat’s hull below water quite clearly; yet even now he withheld a little longer: he meant to wait till all his guns would bear on the German. Any sensitive person would have experienced a weird shiver as this foreign visitor went on completing her scrutiny, till she emerged on the surface some three hundred yards from the port bow. She was U 83; twenty apprehensive minutes had given her satisfaction, and now she could make a more easy inspection without fear. There was no sign of a “trap-ship” - as the Germans called the Q-ships. All the crew were away in boats to starboard. Confidently U 83 motored down the Farnborough’s port side.

That was just where the British steamer wished her. Everything now happened. At point-blank range the Farnborough’s guns opened fire, shattering hull and conning-tower. Forty rounds were loosed off with dispatch, and the Maxim gun rattled away, too. Thus was U 83 beaten at her own game, and she sank with her conning-tower open. Instantly the Farnborough’s lifeboats went to the assistance of survivors, one officer and one man being picked up and taken back to a ship that was sinking by the stern. Engine-room, boiler-rooms, and Nos. 3 and 4 after-holds of the Farnborough rapidly filled. Death by drowning or starvation seemed now more certain than ever. At 11 am from this desolate Atlantic spot Commander Campbell wirelessed his farewell to Admiral Bayly at Queenstown:

“Q 5 slowly sinking respectfully wishes you good-bye.”

Any Commander-in-Chief would have been less than human had he remained unmoved by such a signal from such a courageous officer, and from one who a little while before had feared that he would never meet the foe.

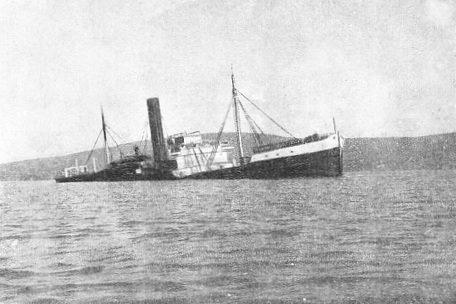

“Q 5 SLOWLY SINKING RESPECTFULLY WISHES YOU GOOD-BYE”, was the message received by Admiral Bayly from Commander Campbell after Q. 5’s successful engagement with U 83. But the gallant Farnborough did not sink; she was safely beached at Berehaven (Ireland), after which she went back to the merchant navy as a cargo-carrier.

But the end was not yet. A British destroyer had picked up the Farnborough’s signals and arrived before noon, taking off all except a dozen officers and men. Next came HMS Buttercup, who got the Farnborough in tow, and presently came HMS Laburnum. But the water was steadily gaining, and by two o’clock the following morning the Q-ship listed alarmingly, so the twelve were ordered into the boats. A depth-charge exploded. This was a large bomb which, having been dropped over a submerged submarine, would either seriously damage her or destroy her by explosion. The depth-charge exploded so vehemently that Buttercup thought it was another submarine’s torpedo, and slipped her tow. At daybreak Campbell returned to his vessel. Laburnum now took her turn of towing, and late that night the Farnborough arrived at Berehaven, where she was beached. I never saw any vessel in so deplorable a condition. But the Farnborough was patched up and eventually went back to the Merchant Navy as cargo carrier. This was a wonderful bit of salvage, and a notable reconditioning of terrible wreckage.

For his “conspicuous gallantry, consummate coolness and skill in command of one of his Majesty’s ships in action” Commander Campbell was awarded the Victoria Cross; but, because no details were published, he was soon known as the “mystery V.C.” Nor did he long remain on shore. Having been given another collier, he brought with him his old gallant crew and went to sea in the 2,817-tons Pargust, whose fitting out he superintended. True, she was excellently armed with one 4-inch gun, four 12-pounders, two Maxim guns and even two 14-inch torpedoes; yet she could do only seven and a half knots. On the other hand, she looked exactly what she was intended to appear: a perfect “gift” to a hungry enemy, who was not to learn that, thanks to her carefully stowed cargo of timber below, this steamer would not sink quickly.

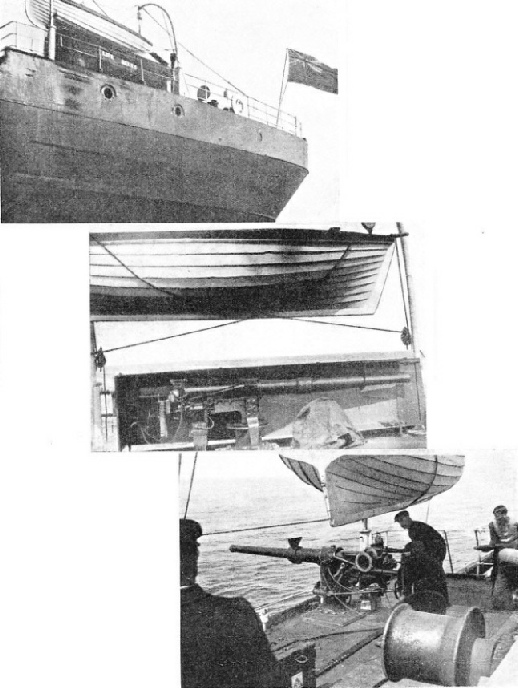

THE PLIGHT of the American Q-ship Santee with her decks awash after she had been torpedoed. The Santee was the only American “mystery ship” put into service during the war of 1914-18. When the USA declared war on Germany in 1917 the submarine menace was at its height. Although torpedoed, the Santee was able to reach port.

THE CAMOUFLAGED HULL of the Santee gave her the appearance of the ordinary war-time cargo vessel with striped sides. The object of camouflaging - practised both at sea and on land - was to render ships, guns and equipment less conspicuous. This illustration of the Santee shows her just before her departure to lure the undersea enemy.

On June 7, 1917, this single-funnel decoy was once more back in the old Atlantic area. It was an unpleasant Irish day with damp and mist turning to rain, and with the sea in a wild mood. No weather for rowing about in small boats, and not the most preferable conditions if any holed ship expected to reach port. She could have but the remotest hope of floating into harbour - unless the timber supported her long enough.

Everything happened quickly and the drama began without prelude. It was 8 am when, out of the mist and from short range, a torpedo was seen rushing towards the Pargust’s starboard beam; a few seconds later it had torn a large hole in the hull near the waterline and blown the starboard lifeboat, into the air. The waves began to fill the boiler-room and engine-room, as well as No. 5 Hold.

“Abandon ship!”

Away went the “panic party” in three boats. A periscope was then sighted some 400 yards away on the port side; presently it approached to within 50 yards of the starboard quarter, when the submarine partly rose to the surface. A man’s figure appeared on the conning-tower shouting at one of the boats, which wisely rowed away so as to leave a clear scope for the Q-ship’s guns. At 8.36 all the guns were now bearing nicely, and Campbell gave the signal. The first shot from his 4-inch struck the conning-tower and knocked off both periscopes. About forty more shells hit conning-tower and hull, so that UC 29 took an ugly list. In fewer than five more minutes an explosion occurred in the forward part of the submarine, and that was the end. She fell over on her side in the manner of a great steel whale and was swallowed by the waves. Two survivors were picked up - an officer and an engine-room petty-officer.

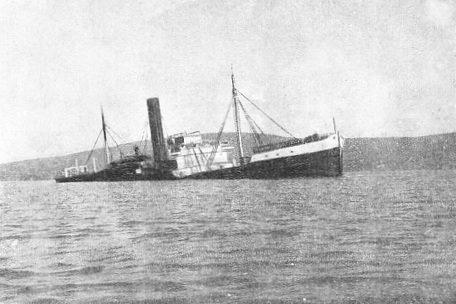

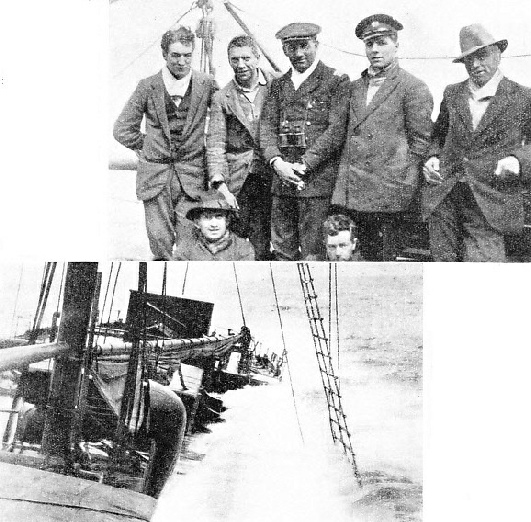

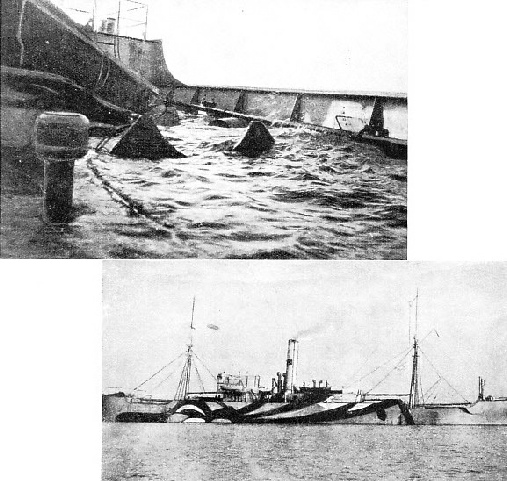

DISGUISED OFFICERS of the Q-ship Zylpha. The officers and men who volunteered for this hazardous service were drawn from every category of the sea - Royal Navy, Royal Naval Reserve. Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and Royal Fleet Reserve, and came from all types of craft to help combat a threat to Great Britain’s food supplies.

IN ACTION. A photograph (right) of the British “mystery ship” Zylpha taken after she had been hit in an engagement with the enemy. Though the “mystery ships ” by no means always secured a victory, they proved so successful in 1915 that the Admiralty formed a special fleet of these decoys, whose main base was at Queenstown, Ireland.

UC 29 had left Brunsbuttel on May 25 with a cargo of mines, which at this period were being laid to entrap warships and mercantile shipping off the south-west Irish ports and headlands. Already she had deposited some, yet not all; that was proved by the explosion forward where these black “eggs” were stowed.

Luckily, the Pargust’s timber kept the Q-ship from foundering till two small British warships and one American destroyer arrived. But on this occasion Captain Campbell elected to be towed farther than Berehaven; he gallantly insisted that his mauled ship be brought slowly all the way eastwards to Queenstown, hoping that on the way he would be seen by a second submarine which could not resist the bait. The Pargust’s people kept themselves ready for a second encounter, but, to their disappointment, no further chance appeared. She had lost only one stoker petty-officer killed and one engineer sub-lieutenant wounded, and the ship safely gained Queenstown. It is difficult nowadays to indicate the great peril to the British Isles then being caused by submarines. At one period only six weeks’ supplies of food remained. During April, 1917, 155 merchant ships had been sunk, and no island nation could endure such losses for long. Thus the defeat of each German submarine caused an immense satisfaction and won corresponding rewards. Captain Campbell was now given a bar to his D.S.O., and one officer and one man received the Victoria Cross. Obviously the whole ship’s company deserved such a coveted decoration, so selection was made by ballot, the officer being Lieutenant R. N. Stuart, D.S.O., R.N.R. (now a well-known C.P.R. captain), and the rating, Seaman Williams.

Thus we come to the great finale. The Pargust had been so knocked about that it would be weeks before Devon-port Dockyard could complete repairs. Captain Campbell therefore looked round for yet another ship. The collier Dunraven was chosen and fitted out, and the whole surviving crew joined her from the Pargust. Nor was much time wasted, for the new “mystery ship” was commissioned on July 28, and left Devonport on August 6. On August 8 began the biggest duel in all the history of these special service vessels.

The time was 10.58 am, and the place about 130 miles west of Ushant. Many British steamers were then armed defensively with a small (and generally quite inadequate) gun against U-boats. Thus the Dunraven had a 2½-pounder mounted aft; but this was, of course, additional to her concealed armament. To simulate the normal cargo steamer making a passage, and wary of attack, the Dunraven was steering zigzag courses, doing about eight knots, when a submarine showed up on the horizon to starboard. This was UC 71, whose commanding officer, Lieutenant-Commander Salzwedel, happened to be one of the “star-turn” submarine captains of Germany’s Flanders flotilla.

Salzwedel, an officer of great experience, had once commanded UB 10, in which he had sunk steamers off Boulogne. This UB 10 was the boat which had the thrilling experience of fouling the nets across Dover Straits in 1915. Eight hours were spent trying to get clear, and several of our net-mines exploded; yet she managed to extricate herself and return to Flanders. Next Salzwedel was given UC 21, and now, with a still more modern craft, he had come right out into the Atlantic. The meeting of these “aces”, each ignorant of the other’s identity, could not fail to produce a great occasion. The submarine steered towards the steamer, submerged; but after three-quarters of an hour broke surface 5,000 yards away and opened fire. This was a long range, but U-boat skippers had now learned so much about “trap-ships” that no risks were taken. Campbell replied with his little 2½-pounder, made a lot of smoke, reduced speed to seven knots, and hoped the enemy would come closer. The submarine’s shells kept falling over until 12.25 pm, when she had approached much nearer, turned broadside on, and resumed. So that she could maintain the pretence of being an unfortunate cargo- ship, the Dunraven, besides intentionally firing short, made wireless signals such as “Submarine chasing and shelling me. . . . Submarine overtaking me. . . . Help, come quickly. . . . Am abandoning ship”. All this was for the submarine’s benefit.

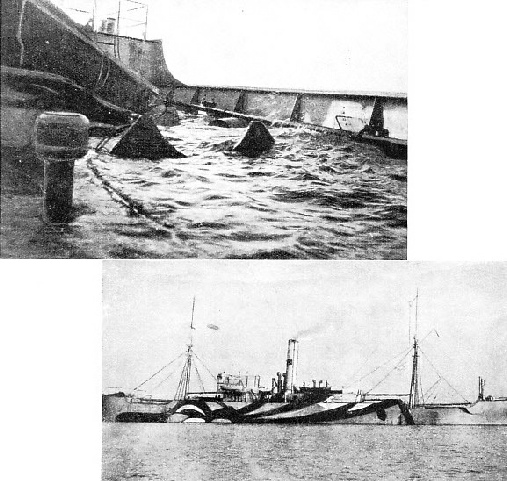

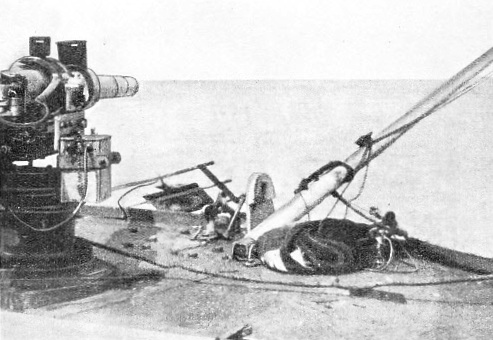

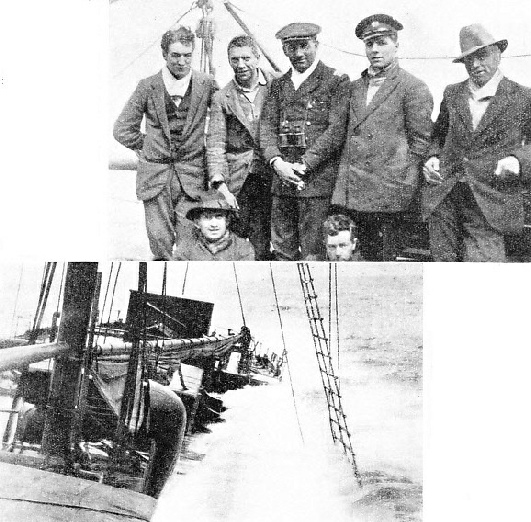

TORPEDOED. A dramatic photograph taken on board the Q-ship Dunraven after she had been hit by a torpedo. This collier, fitted out for special service, engaged the German submarine UC71 in a prolonged duel on August 8, 1917, about 130 miles west of Ushant, off the coast of France. After hours of contest, the fight ended in a draw, but the struggle passed into history as the greatest of all Q-ship exploits during the war of 1914-18.

Salzwedel’s shells began to fall close indeed, whereupon Campbell made a cloud of steam to suggest boilers penetrated, and stopped engines. The Dunraven was turned broadside on and the usual “abandon ship” party went away in full sight of the Germans. To make this bit of acting more realistic, an intentional bungling was made in lowering one of the boats. But still closer motored Salzwedel, and things began to look serious when a shell entered the Dunraven’s poop, exploding a depth-charge and blowing Lieutenant C. G. Bonner, D.S.C., R.N.R., out of his control position. Two more shells also struck this part of the ship, which was now on fire, with dense clouds of black smoke. Immediately below were the magazine and depth-charges, and, although a terrific explosion was bound to ensue, Campbell pluckily withheld and waited for his enemy to get on the weather side.

Bonner had recovered himself and crawled with his men into the gun-hatch, where they remained with the flames raging so fiercely that the deck became red-hot. One man tore his shirt to shreds, which he distributed to his mates to keep the fumes out of their throats. Others lifted the cordite boxes off deck to prevent explosions. By this time all communication with the bridge was cut off. They knew what would presently happen, yet if they moved they would spoil the whole show of pretence.

The inevitable came at 12.58 pm. Just as the enemy passed close to the stern, off went two depth-charges and an explosion of cordite. Up into the air went the 4-inch gun and every one of its crew. The gun came down on the well-deck forward, the crew falling in various parts of the ship, but one man went overboard. The 4-inch projectiles were blown all over the ship, and now the explosion started the alarm buzzers. It was the worst of bad fortune that things should have turned out thus. The enemy had to move only another 200 yards, and three remaining guns would have been able to bear; as it was only that one at the after bridge could do so, and this was fired, dropping a shell close to the submarine, which had begun to submerge after the explosion.

Fifty Exciting Minutes

What next? A torpedo would follow. Campbell knew it too well, and ordered the ship’s doctor to remove all wounded. The hoses were turned on to the blazing poop, and a distant warship (in answer to his previous signal) had replied. Nevertheless, the Dunraven’s captain had wirelessed back, “Keep away for the present”. He still meant to conquer. But Salzwedel, fully aware that this was one of the lifted “trap-ships”, was equally resolved to win. The second phase now began, and at 1.20 pm a torpedo struck the Dunraven abaft the engine-room.

To bluff the German commander and make him think the final party were quitting, Campbell sent away more of his crew in boats and a raft. Fifty exciting minutes were endured from 1.40 pm, as the British commanding officer on his isolated bridge watched the scrutinizing periscope circling around, while Bonner and his wounded men below were lying in pain with heroic quiet as the cordite boxes exploded every few minutes. The conditions became scarcely bearable for the bravest when, at 2.30 pm, the submarine broke surface directly astern (where none of the Dunraven’s guns could bear) and at short range pumped shell after shell into the ship, sending splinters of steel among the sufferers. The physical and moral courage of these disciplined British sailors cannot be expressed in mere words; yet they continued quite cheery and longed only for a victory.

COMPLETE CONCEALMENT. On board the Q-ship HMS Suffolk Coast. This illustration shows the seemingly harmless forward hatch beneath which is hidden a powerful naval gun.

Unable to use his guns, Campbell decided to try his torpedoes, and at 2.55 pm fired one which just missed the submarine's periscope. Salzwedel had not seen this, but he saw the second seven minutes later which passed just astern of his periscope. Another German torpedo would most certainly be the response, so after all these hours of wild contest it was time to call it a draw. The Dunraven wirelessed for urgent, assistance, and soon from below the horizon came three warships - the USS Noma, HMS Attack and HMS Christopher. From the first and third came medical officers to take charge of the wounded, two of whom were transferred aboard Noma and hurried into Brest for treatment.

A nasty sea was now running, Christopher took the stricken ship in tow, but the task seemed hopeless. The poop had been completely gutted, all depth-charges and ammunition having exploded. She was down by the stern, over which Atlantic waves poured and broke. Still the towing went on through that night and all the next day. At 1.30 am of August 9, just after Christopher had with difficulty come alongside to remove the last men, the Dunraven succumbed in her final agony. She went down stern first, and the greatest of all Q-ship duels passed into history. Captain Campbell was awarded a second bar to his D.S.O., and Lieutenant Bonner the Victoria Cross; to other officers and men other decorations most rightly and meritoriously were given. His Majesty King George V, speaking of the action, said “Greater bravery than was shown by all officers and men on this occasion can hardly be conceived”.

There were many other notable “mystery ship” episodes performed before the war ended.

This chapter has told the story of the disguised steamer, pretending to be a harmless tramp or collier. The work of these “mystery ships” in the war of 1914-18 was a valuable contribution to the conquest of the submarine menace.

But there were other “mystery ships” still frailer and more helpless in appearance. These were the disguised sailing ships, whether schooners or fishing smacks. The schooners successfully performed tasks analogous to those of the disguised steamers. The smacks, employed as decoys to counteract submarine attacks on the British fishing fleet, likewise gave an excellent account of themselves.

But “mystery ships” were not confined to the British and Allied Navies. One of the most spectacular achievements of the war was the cruise of the German commerce-raider Mowe. This fine sailing ship all but achieved the impossible in her career across the ocean.

This and other sailing “mystery ships” will receive their due share of attention as this work proceeds.

READY FOR ACTION. The forward hatch of HMS Suffolk Coast uncovered, showing the gun and its crew. Early Q-ships were lightly armed, with possibly not more than two 12-pounder guns, but later ships increased their armament, and one, the 2,817-tons Pargust, had one 4-in gun, four 12-pounders, two Maxim guns and two 14-in torpedoes.

You can read more on “The Convoy System”, “Epics of the Submarines” and

“Troopships & Trooping” on this website.