© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Scott’s Gallant Failure

The Antarctic Expedition of 1911 stirred the imagination of people throughout the world and gained for Captain Scott and his heroic companions a place among the immortals

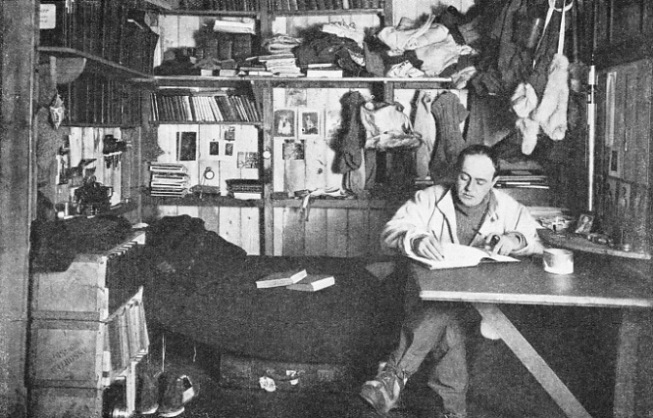

AN UNUSUAL PHOTOGRAPH of the great explorer Captain R. F. Scott, R.N., writing in his diary. Captain Scott sailed for the Antarctic in November, 1910, on an expedition to the South Pole. After terrible hardships, Scott, with four other members of his party, reached the Pole in January, 1912, only to find that the Norwegian explorer, Roald Amundsen, had preceded him. On the return journey from the Pole to his base Scott and his companions perished from lack of food.

WHEN Capt. Robert Falcon Scott, R.N., went south from his base for the second time, he planned to continue the scientific work he had carried out in the Discovery (1902-

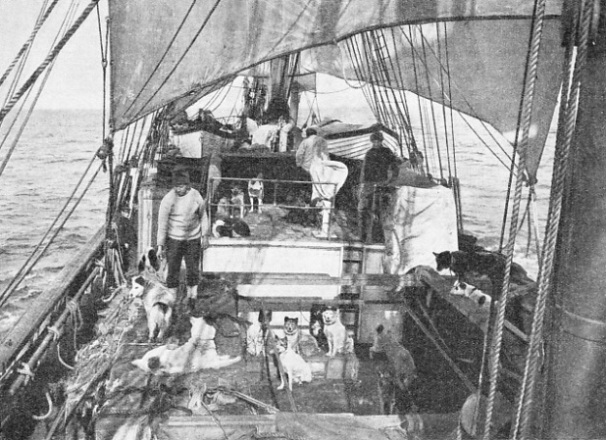

On November 26, 1910, Scott sailed from Lyttelton, N.Z., in the Terra Nova, an old whaler that had served as relief ship to the Discovery in 1904. He had an eventful passage south. Caught in a gale, the ship lay-

Before losing touch with civilization, Scott had learned that a formidable rival was in the field. A telegram received at Melbourne read: “Madeira. Am going south.— Amundsen.” Roald Amundsen, the Norwegian explorer, had been in the Antarctic before Scott, having been mate of the Belgica, the first ship to winter in the Antarctic (1898-

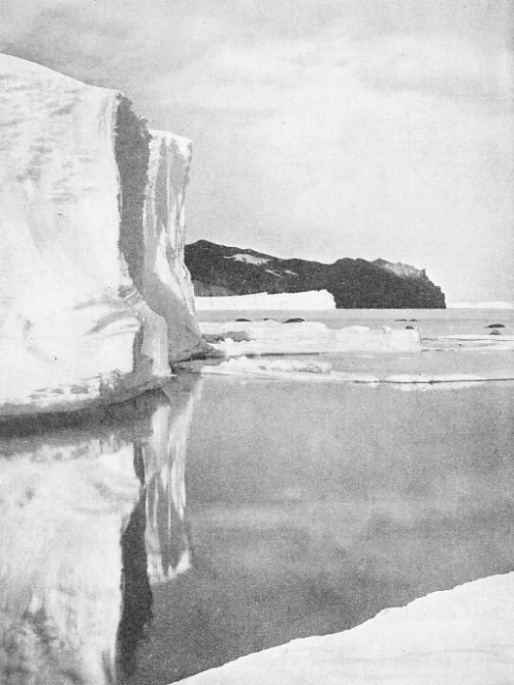

NEAR THE BASE CAMP at Cape Evans -

Amundsen, already famous as the first man to make the North-

With the return of the sun, there would be a race for the Pole, in which the Norwegian clearly held the advantage. He was some sixty miles in a direct line nearer the goal, and he and his men had been accustomed to ski-

Glacier than Scott was, and he was risking not only his dogs, but also his whole expedition, by wintering on the Barrier -

Deciding not to change his plans, Scott began his great journey to the Pole on November 1, 1911. His first objective was to get three sledge teams of four men each to the foot of the Beardmore, in lat. 83½° S. To do this, every available form of transport was pressed into service -

Warned by past experience, Scott kept well clear of the dangerously crevassed region off White Island. The Barrier surface was in bad condition for sledging and the weather abnormal -

By November 23 the last sledge was past 81° S., and thus only 150 miles from the rendezvous at the foot of the Beardmore. All the ponies were still pulling strongly and the weather was better; the sun was shining, and the surface, therefore, had improved. But next day the weaker ponies showed that they had almost reached the limits of their endurance, and Jehu, the weakest, was shot. Chinaman met the same fate next day and Christopher on December 1. The work of these plucky animals being nearly done, their end was inevitable yet merciful. Neither ponies nor dogs could be taken up the Beardmore; the dog-

Near the foot of the Beardmore came a minor disaster. A blizzard raged and howled round the camp for four days on end. The temperature was comparatively high (+ 33° Fahr.) and the snow, melting as soon as it fell on the tents, dripped incessantly inside them, soaking everything. Advance was impossible; it was sufficiently difficult to keep the ponies fed and the men cheerful.

The situation was serious. The pony forage was almost finished and the men, several days behind schedule, had been compelled to break into the rations intended for the climb up the glacier. Their chance of reaching the Pole had almost vanished. Shackleton, favoured by better weather, had reached the present position six days earlier in the season; yet he and his men, going to the limit of human endurance and risking death on every mile of the return journey, had been forced to turn back short of the Pole. It was doubtful whether Scott’s party could even reach his “Farthest South”.

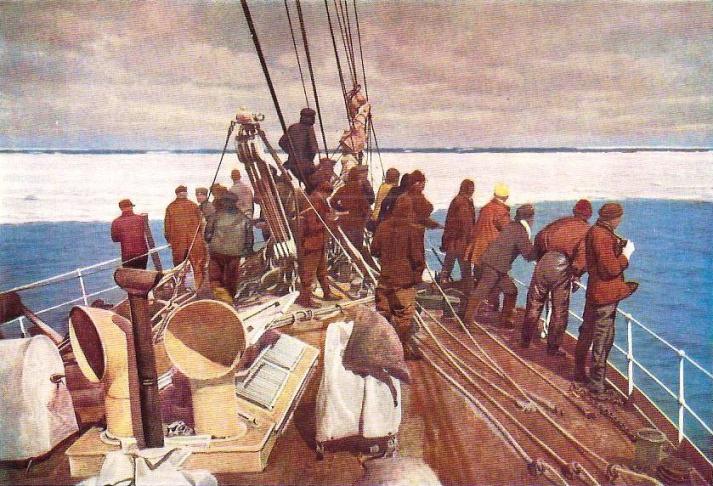

SOUTHWARD BOUND. A view from the engine-

On the morning of December 9 they got away at last over an appalling surface, and evening saw them encamped at the glacier foot. Here, at “Shambles Camp”, the worn-

The long haul up the Beardmore Glacier was regarded, with reason, as the hardest part of the journey. It seemed unlikely, therefore, that they would be able to regain any appreciable part of the six days they had lost. But Scott determined to attempt it. Although well over forty, he led the climb, harnessed and on skis, at a pace which left the younger men of the party gasping. He spared neither them nor himself. He skirted crevassed areas by what seemed to be the possession of a sixth sense. He was always striving to gain height, fighting indefatigably against unexpectedly difficult conditions. Shackleton had found hard, blue ice where Scott’s men were pulling heavier loads through soft snow, knee-

It was hard pulling every yard of the way. Half-

Scott’s own sledge-

Rope Rescue

Captain Oates, of the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons, who was the able officer-

PRELUDE TO ADVENTURE. Captain Scott’s ship, the Terra Nova, entering the pack ice of the South Polar regions. The Terra Nova left Lyttelton, New Zealand, over eleven months before Scott began his great journey to the South Pole from the base camp at Cape Evans. On the voyage south the ship was caught in a gale and narrowly escaped foundering. Later she was imprisoned for three weeks in an ice-

Lieut. Evans, Lieut. H. R. Bowers (Royal Indian Marine), Petty-

Left to their own resources, the two teams were able to move slightly faster, showing, as Scott noted, that he had correctly allotted the weakest pullers to the returning party. He steered southwest for a day, to escape from a maze of crevasses, and then due south. The surface was still bad, but the sun shone in a cloudless sky. All were cheerful and looking forward to a satisfying meal -

Christmas Day found them dodging crevasses once more. Lashly crashed into one and hung in his harness while the sledge bridged the gap above him. He was rescued eventually by the Alpine rope carried for such emergencies and, as it was his birthday, was received with a chorus of greetings. For the first and last time they had a four-

Christmas Day found them dodging crevasses once more. Lashly crashed into one and hung in his harness while the sledge bridged the gap above him. He was rescued eventually by the Alpine rope carried for such emergencies and, as it was his birthday, was received with a chorus of greetings. For the first and last time they had a four-

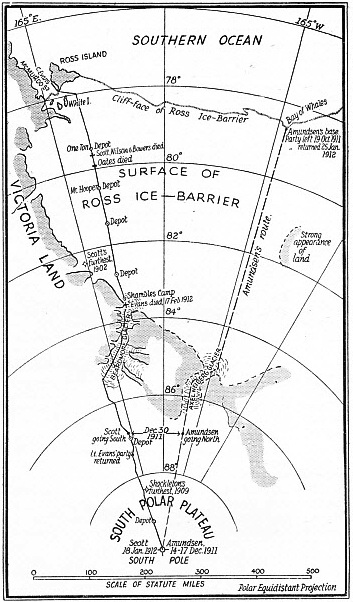

ROUTES OF THE TWO POLAR EXPEDITIONS are shown on this map. The two expeditions were nearest to one another on December 30, 1911, when Scott and Amundsen were in lat. 87° S., although 100 miles apart. But at that date Scott’s party were wearily plodding on foot to the Pole, while Amundsen, who had found a practicable approach to the Polar Plateau for his dogs, was hastening homewards.

Next day they crossed 86° S. and were averaging fifteen miles a day as against Scott’s scheduled ten. Going so strongly, on the last day of the year they caught up with Shackleton’s dates. Scott promptly took the first opportunity of resting his men, and at the same time reducing the labour ahead of them. The two 12-

New Year’s Day, 1912, saw the party again under way with the smaller sledges, Scott’s team outdistancing the others, who, except Bowers, were showing signs of strain. Otherwise, prospects were generally brighter, since they were only 170 miles from the Pole and had plenty of food.

Next day Scott made his final choice of the Polar party and told off Lieut. Evans, Crean and Lashly to return, keeping Bowers with his own team. It was a singular and risky decision. Bowers, who was the fittest man of the eight, deserved his place; but all the supplies and equipment had been calculated and apportioned for four-

On January 4 the supporting party turned over all except four days’ provisions to the Polar party, with whom they marched south to 87° 34' S., to observe progress. Bowers, who disliked skis and had shed his at the last depot, was pulling on foot in the centre position, the other four being on skis. Satisfied that all was going well, Evans and his men gave “three huge cheers” and turned about. A final backward look showed them five little black dots on the southern horizon -

The return of Evans’s team was an epic in itself. Evans developed scurvy on the way down the Beardmore, and at One Ton Depot he could not stand without his ski-

Meanwhile the Polar party were pressing on. They had food for a month, apart from that in the depots, and the Pole was only 150 miles away. The surface, covered with ice-

On January 15 they made their last depot of four days’ food and all surplus gear, and camped twenty-

The two parties, each of five men, had been at their nearest on December 30, a fortnight earlier. Both were in 87° S., about 100 miles apart. But while Scott’s men were painfully hauling their sledges towards the Pole, Amundsen’s dog-

There was little sleep in the English camp that night. Determined to make sure of the worst, next morning they followed the Norwegian tracks for some distance and then headed straight for the Pole. That night they camped, chilled to the bone. Bowers took observations for position with the theodolite sad determined that they had overshot she mark, being about a mile beyond it

“and 3 to the right” (north is the only direction at the South Pole). He noticed a small tent, and in the morning of Thursday, January 18, they came up with this. It was Amundsen’s spare tent, with its central bamboo proudly the Norwegian flag above the Fram’s pendant. Inside were some discarded instruments and gear, and a record dated December 16, 1911, signed by Amundsen and his four companions -

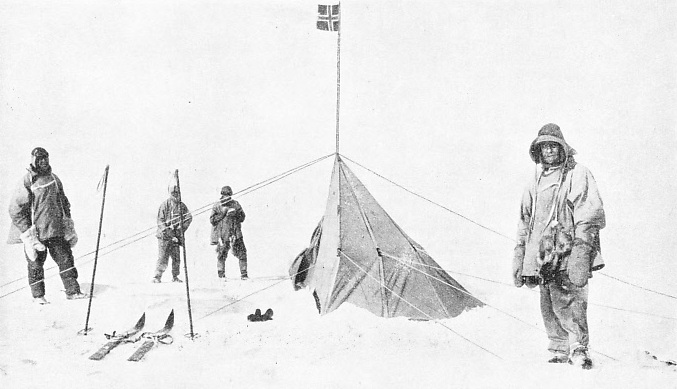

The five weary men camped for lunch, and then built a cairn on the site approximating as nearly to the Pole they could determine. The Norwegians had done the same, and the two carins were less than half a mile apart. Scott’s party hoisted a Union Jack, took a photograph and began the long homeward journey. In the entry relating to his forestalment in his private journal Scott makes no complaint of his disappointment. He praises the accuracy and thoroughness with which the Norwegians had staked their claim, and his sorrow is all for his “loyal companions”. But in a later entry appears this sentence: “Great God! this is an awful place and terrible enough to have laboured to it without the reward of priority!”

Impending Doom

It was to be more terrible in the dreary days that followed. Gale after gale descended on them in clouds of drifting snow. Sometimes they pulled doggedly on; sometimes they were forced to camp. But, as they slowly made their way to the Beardmore and began to descend it, the shadow of something graver than mere physical hardship began to deepen about them.

The strongest man of the party, Petty-

The end came at the foot of the Beardmore on February 17. Soon after starting, Evans fell out twice to adjust his ski. The rest continued and camped for lunch while he was still a long way behind. After the meal, as he seemed no nearer, they hastened back. Scott, first on the scene, found Evans on his knees in the snow, staring wildly about him, his hands bare and frostbitten. He collapsed in their arms, and while Oates stayed by him, the others brought the sledge back and hurriedly rigged the tent. But Evans was comatose when they got him into it and in a short time he was dead. Wilson diagnosed the immediate cause of his death as concussion, due to his falls on the Beardmore. It was typical of the man that he should have gone on uncomplaining until he dropped.

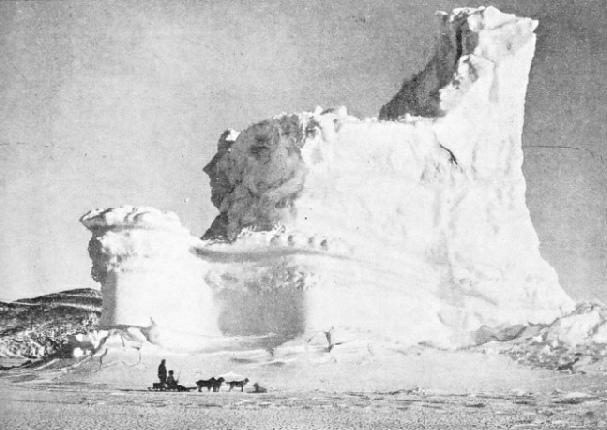

THE CASTLE BERG, a remarkable formation of snow and ice photographed by the late H. G. Ponting, official photographer to the expedition. An idea of the vast size of the berg can be obtained by comparing it with the two men and the sledge with a dog team in the foreground.

Sorely shaken, the four buried their comrade and pushed on to Shambles Camp. Here there was plenty of horse-

All four knew that it was a desperate race for their lives. Their stamina was failing fast and the gruelling toil at the drag-

By March 6 Oates could no longer pull, and he could scarcely walk. They were then sixteen miles short of the next depot, Mount Hooper, in 80° 34' S., some 200 miles from the base. They reached Mount Hooper on March 10, to find the accustomed shortage of fuel and a stock of food insufficient, with their shortened marches, to carry them to One Ton Depot.

“A Very Gallant Gentleman”

Next day Scott ordered Wilson to hand over to them from the medicine bag the means of ending their lives, if need be. Still they went forward, Oates staggering along with hands and feet almost useless, the others pulling feebly. One Ton Depot was fifty miles ahead, with ample food and fuel, but at their present rate of progress they could never hope to get there.

On March 15 Oates could go no farther. He begged them to leave him in his sleeping-

The blizzard abated the following day, and the three survivors went slowly on. As a last resort they abandoned their theodolite, camera and surplus gear, but still dragged, at Wilson’s request, 35 lb. of valuable geological specimens obtained on the Beardmore. Scott had become very lame, his right foot being badly frostbitten.

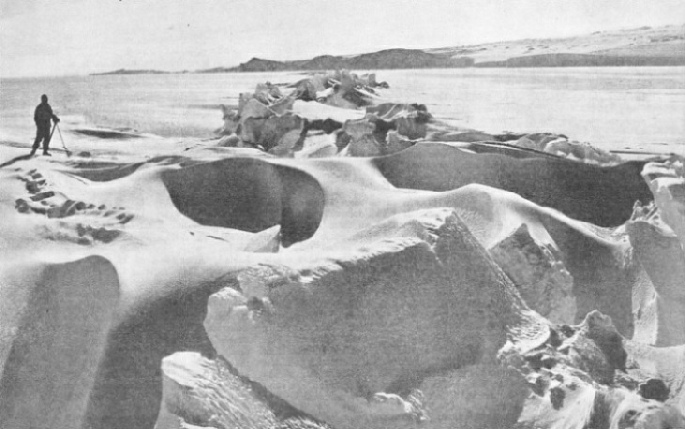

PRESSURE RIDGES. A curious formation of ice on the frozen surface of the sea. On the outward voyage to the south, Scott’s Terra Nova was jammed for three weeks in pack-

On Tuesday, March 20, having barely two days’ food and a day’s fuel left, they were delayed by another blizzard. On the next day they made their final march and camped within eleven miles of One Ton Depot. Wilson and Bowers planned to make a dash to reach this next morning and bring fuel. But the attempt was never made. For a week a W.S.W. gale blew continuously. Every day, until they grew too weak to stand, the three men waited for a chance to start out for the depot. During those days Scott wrote many letters. There is no self-

Eight months later Dr. Atkinson, starting from Cape Evans, went southward with all available hands to discover, if possible, the fate of the Polar party. It was thought that they had probably been lost in some crevasse on the Beardmore. The searchers camped at One Ton Depot on November 11. Early next morning C. S. Wright, the Canadian physicist, who was leading the party, sighted, eleven miles south of the depot, an object which he took to be a cairn. Approaching, he recognized it as Scott’s tent, partly buried in snow. It had been well pitched, and had withstood the winter gales.

Inside were the bodies of Scott, Wilson and Bowers, frozen, but still recognizable. Wilson and Bowers lay as though they had fallen asleep, the hoods of their sleeping-

When all had been recovered, Dr. Atkinson read to his party, at Scott’s written request, the “Message to the Public” and the account of how Oates went to his death. Then a large cairn surmounted by a rough cross was built over the tent and bodies, and the Burial Service was read. The depot-

Dr. Atkinson’s party marched southward for twenty miles, but round the spot where Oates had died the snow-

Having paid fitting homage to the dead, the search-

The Scott Polar Institute, at Cambridge, was built and endowed from the funds left available after full provision had been made for the Polar party’s dependants. And even if no trace now remains of the cairn near One Ton Depot, the memory of the three who rest below it, and of the two who lie farther southward, will endure so long as men prize the highest form of courage.

No one can doubt that if Scott, Wilson and Bowers had put their own safety first, or had yielded to their sick companion’s reiterated plea, they would have escaped a terrible death. Instead they showed, as did the men of the Birkenhead, that they had

... no thought,

By shameful strength, unhonoured life to seek.

Our post to quit we were not trained, nor taught

To trample down the weak.

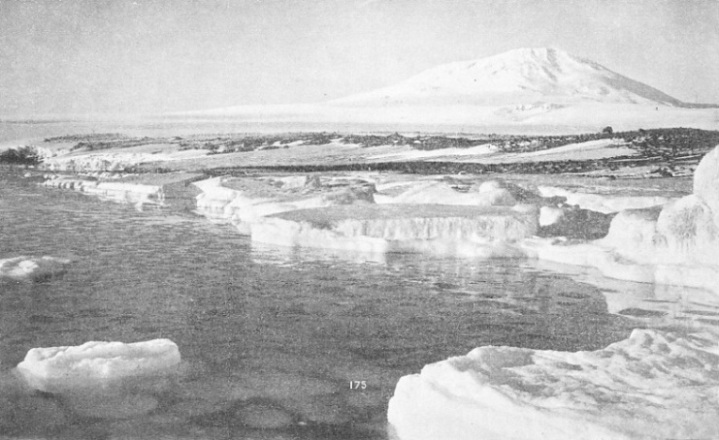

PANCAKE ICE forming into floes. Members of the expedition observed that when the sea froze sheets of floating ice driven by the wind would sometimes override one another and so produce a medley of high-

The causes of the Scott tragedy have often been discussed. The disaster itself came as a stunning blow, both to the general public and to those who knew something of the conditions governing Antarctic exploration. At first sight, it seemed incredible that a most experienced leader, with a picked party and first-

Many have contended, both at the time and subsequently, that the real reason was an outbreak of scurvy among the Polar party; but this is not warranted by the facts. The only authenticated instance of this terrible disease known to have occurred in the whole expedition is that of Lieut. Evans; but this did not prove fatal because of the heroism shown by his companions.

Lieut. Evans had already done months of preliminary sledge work before starting on the main southern journey, and the extra strain which his keenness and zeal had imposed upon him sufficiently explains why he, and no one else in the whole expedition, developed scurvy. There is no evidence at all that any member of the lost Polar party showed any symptoms of it. The real reasons are those given in Scott’s “Message to the Public”, and fully confirmed by later research. The principal factor was the extraordinarily low temperatures experienced on the Barrier during the return journey. The meteorologist of Scott’s expedition, Dr. G. C. Simpson, has pointed out that these were entirely abnormal and could not possibly have been foreseen. Travellers in the Antarctic are, of course, inured to low temperatures, but nothing can be done to mitigate the enormous extra exertion which such temperatures impose upon men who are drawing sledges.

An account of Scott’s last expedition would be incomplete without some reference, however short, to the adventures of his northern party. This consisted of six men only, and was led by Commander V. L. A. Campbell, R.N., the other members being Surgeon G. M. Levick, R.N., Mr. R. E. Priestley (geologist) and three seamen, Abbott, Browning and Dickason.

It had been intended that they should be landed by the Terra Nova in King Edward VII Land, with stores and equipment, and explore this region independently. But, as already stated, this programme was frustrated by the discovery that Amundsen was wintering in the Bay of Whales, and had therefore secured, so long as he remained there, a prior right of exploration in the

neighbourhood of this Antarctic Bay. The Terra Nova therefore steamed up the coast of Victoria Land, and put Campbell and his party ashore (February 1911) at Cape Adare, its northern extremity. Here they erected their hut and wintered, close to the hut built ten years earlier by Borchgrevink’s Southern Cross expedition -

But before this period was over many miles of closely-

AT THE SOUTH POLE. On Thursday, January 18, 1912, Captain R. F. Scott and his four companions reached their goal and discovered that they had been anticipated by Amundsen, who had left behind a spare tent flying the Norwegian flag. Inside were discarded instruments and gear, a record signed by the Norwegian party, also a letter addressed to the King of Norway, with a covering letter to Scott After a cairn had been built and the Union Jack had been hoisted, Scott’s disappointed party began the fatal! homeward march.

You can read more on “The Franklin Mystery”, “South with Shackleton” and

“To the Uncharted South” on this website.