The last of the great naval victories of Lord Nelson took place off Cape Trafalgar on October 21, 1805, and decisively established for Great Britain a sea supremacy that was not challenged for more than a century

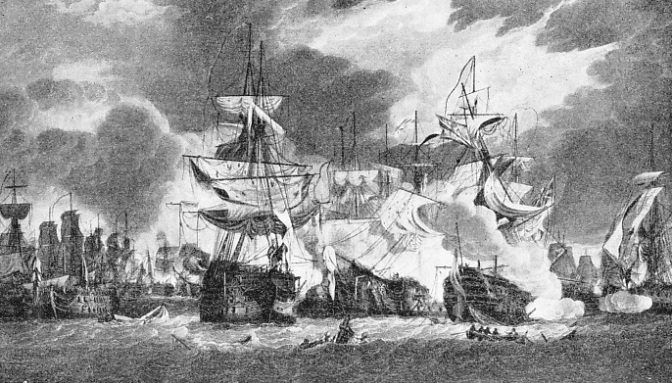

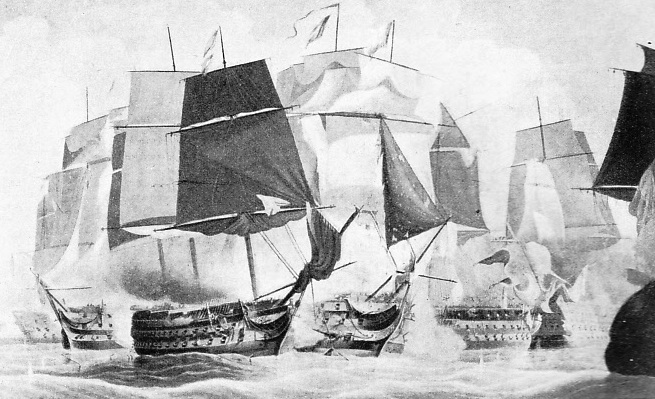

CLOSE-RANGE FIGHTING developed when the Victory, Nelson’s flagship, had broken the line of the Franco-Spanish fleet at the battle of Trafalgar. This illustration, the original of which dates from 1807, shows HMS Neptune in the left foreground. Between her and the Santisima Trinidad (right foreground) are concentrated the Fougueux, HMS Temeraire, the Redoubtable and HMS Victory.

TWO years after the battle of the Nile Lord Nelson returned to England, and on the first day of 1801 was appointed Vice-Admiral of the Blue. The frustration of Napoleon’s plan against India, and the great success won by the Royal Navy, had confirmed Great Britain’s position as mistress of the seas. This inevitably aroused the jealousy of the Continental Powers.

In northern Europe a kind of union, under the name of Armed Neutrality, was formed by Prussia, Denmark, Russia and Sweden, This organization created suspicion in England, where it was believed to be only a preliminary to an alliance with the French. A fleet therefore was sent to Denmark. Lord St. Vincent was now First Lord of the Admiralty, and he sent Nelson as Second-in-Command under Sir Hyde Parker to the Baltic, but the victor at the battle of the Nile soon found Parker “a little nervous about dark nights” and not quite the ideal he had experienced when serving under the stern and purposeful St. Vincent.

Nelson was not happy on this expedition. “I experienced,” he wrote, “in the Sound the misery of having the honour of our country entrusted to a set of pilots who have no other thought than to keep the ships clear of the danger, and their own silly heads clear of shot”. On April 2, 1801, an attack was made against Copenhagen, where the water is shallow, but after a daring fight —causing heavy losses on either side — every ship opposed to Nelson was destroyed, including six battleships. The victory of Copenhagen brought about a dissolution of the so-called Neutrality. In 1802 France, being wearied of war, signed with Great Britain the Peace of Amiens.

Naval officers have often remarked that politicians and statesmen are too prone, by signing treaties, to give away all that has been won by hard fighting. The Peace of Amiens was a fair instance. With certain exceptions, the agreement made Great Britain restore her conquests, so that in effect it became rather an armistice — a state of suspended hostilities — giving the enemies of Great Britain time to turn round and renew schemes for aggrandizement. The Napoleonic scare, far from being dead, flamed forth with more activity.

Thus in May 1803 it was scarcely surprising that war had to be declared against France and Spain, but luckily the Commander-in-Chief in the Mediterranean was Nelson. To neutralize the enemy’s efforts, Great Britain adopted her time-honoured method of blockading, but on a large scale. While Cornwallis operated with his squadron off Brest, Calder off Ferrol, in northwest Spain, and Orde off Cadiz, in southwest Spain, Nelson blockaded Toulon. There were French squadrons also in Rochefort and Lorient.

Napoleon’s oriental plan had been killed once and for all by the battle of the Nile, and he had now reverted to his original idea of invading England. By this time, however, he had learned that command of the sea must first be won, or his army would be endangered as it had been in Egypt. If only he could have the English Channel free and secure for his transports, all would go well; the question was, how could he get rid of the British fleet? This he decided must be done by a clever feint. His plan was to divert Great Britain’s attention from the English Channel to the other side of the Atlantic, so that, with the country’s protection withdrawn, his troops might land on English soil in safety.

Napoleon planned to make a concentration of the French fleets and squadrons in the West Indies at Martinique, whence they were to return to Europe and proceed to the English Channel. Having enticed Nelson out of the way, Bonaparte hoped by the power of the Franco-Spanish fleet to ensure safe transit for his soldiers from Boulogne to England. The Rochefort squadron got to sea, made for the West Indies and was chased by Cochrane. In March 1805 the French Mediterranean fleet from Toulon likewise escaped through the Straits of Gibraltar and made for the West Indies. The admiral of this fleet was Villeneuve, who had commanded the French rear division at the battle of the Nile.

Thus the invasion operation pivoted on the fleet, and even during 1803 French flat-bottom vessels were being collected. These measured 120 feet long with 40 feet beam, and were rowed by eighteen oars a side; they carried also a squaresail and flying topsail on the mast. Designed to carry 500 soldiers, each of these barges was fitted with a gangway or drawbridge in the bows for landing on the beach, and a powerful capstan was added for working the anchors.

The fleet, however, failed to provide the essential security, so that the invasion scheme collapsed. Villeneuve reached the West Indies, but he was not joined there by the Brest fleet. The British blockading forces made it impossible for the Brest fleet to emerge. The hoped-for concentration never matured and the Boulogne camp was broken up. Nelson had indeed been enticed across the Atlantic, but he came back to Europe without having found Villeneuve. The French admiral, having sailed eastwards over the ocean, made Ferrol, encountering Admiral Calder’s squadron and losing two of the Spanish ships. From Ferrol the French admiral later managed to escape to Cadiz while most of the British fleet were off Brest. Nelson raced back from the West Indies into Spanish waters before his enemy, and the first phase came to an end.

Historic Memorandum

In August of the memorable year 1805, which was to be his last, Nelson came home to England for a short while, though long enough to learn how much the country loved him. “I met Lord Nelson in August, 1805, in a mob in Piccadilly”, wrote Lord Minto. “I got hold of his arm so that I was mobbed too. It is really quite affecting to see the wonder and admiration and love and respect of the whole world”.

Less than a month afterwards, Captain the Hon. Henry Blackwood, R.N., brought to Nelson at Merton, Surrey, news of the Franco-Spanish fleet’s arrival in Cadiz, and the two officers went straight up to London. At the Admiralty Lord Barham willingly accepted Nelson’s services, and the great statesman Pitt went out of his way to be courteous, even to the extent of seeing the admiral into his carriage. We shall never know the exact conversation between these two illustrious Englishmen, either of whom had fewer than six months more to live, but we can get a suggestion from the contents of a letter which Nelson wrote a few weeks later dated on board the “Victory, 16 leagues West from Cadiz, October 6th, 1805”. In this letter he remarked, “It is, as Mr. Pitt knows, annihilation that the Country wants, and not merely a splendid Victory of twenty-three to thirty-six — honourable to the parties concerned, but absolutely useless in the extended scale to bring Buonaparte to his marrowbones; numbers only can annihilate . . . therefore I hope the Admiralty will send the first force as soon as possible, and Frigates, and Sloops of War”. He needed the frigates and sloops for the purpose of watching the enemy’s movements.

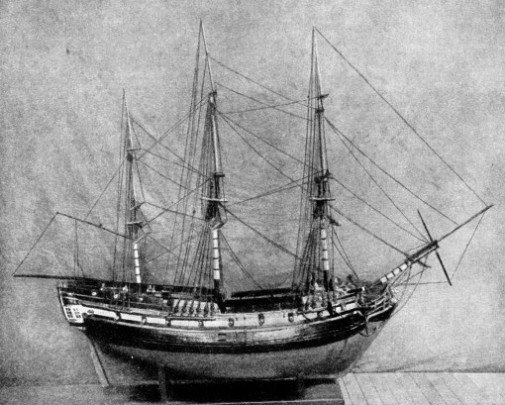

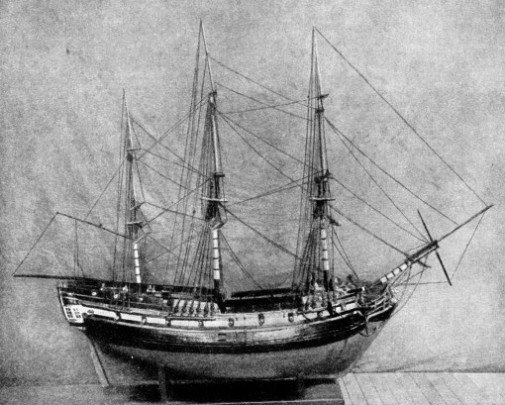

A BRITISH WARSHIP of a type that was superseded shortly after the battle of Trafalgar in 1805. H.M.S. Prosperity, of which a model is shown here, somewhat resembled, in her rig and the shape of her hull, the 64-guns ships in the Royal Navy at that time, but she carried a much lighter armament.

The climax of Nelson’s busy life was fast approaching, and he had now to prepare himself with his fleet for the heaviest of all tasks. At the end of September he was with his fleet and on board the Victory off Cadiz. From his correspondence we can see well into his mind, and understand his thoughts. “Day by day, my dear friend”, he wrote from his flagship to Alexander Davison,

“I am expecting the [Franco-Spanish] Fleet to put to sea — every day, hour, and moment; and you may rely that, if it is in the power of man to get at them, that it shall be done; and I am sure that all my brethren look to that day as the finish of our laborious cruise . . . I have two Frigates gone for more information, and we all hope for a meeting with the Enemy. Nothing can be finer than the Fleet under my command”.

Only a fortnight before the battle Nelson wrote to another friend, “I verily believe the Country will soon be put to some expense for my account, either a Monument or a new Pension and Honours; for I have not the very smallest doubt but that in a very few days, almost hours, will put us in Battle; the success no man can ensure”.

Long before the battle he had formulated his plans, and we can picture him in his cabin writing that historic Memorandum on October 9. The original holograph draft of this document was for many years in private hands, but in 1910 it was secured for the nation and now remains in the British Museum. Its historical value is all the greater because Nelson’s death deprived us of that invaluable report which as Commander-in-Chief he would have written to the Admiralty. There has been some controversy as to whether the great admiral did or did not carry out the intentions embodied in the Memorandum, but it is conceded he did so far as the main idea was concerned.

Nelson decided on the principle of placing his own fleet in two lines, with himself in command of one line and Collingwood in command of the other. Nelson intimated he would “probably make the Second-in-Command’s signal to lead through” the enemy’s line at “about their twelfth ship from their rear”, and Nelson’s own line would lead through about their centre. The whole impression of the British fleet must be to overpower the enemy, from a point two or three ships ahead of the enemy’s Commander-in-Chief (expected to be in the centre) to the rear of that fleet. This was, in the fewest words, the plan made twelve days before the historic battle, and in general these principles were carried out.

Nelson's Last Letters Home

Two days before the event, having done all he could and still waiting for the hour of contact, being now 16 leagues west-south-west of Cadiz, Nelson was free to write letters and enjoy the pleasant autumnal weather that could not last much longer. So at noon of October 19, a windless day, he sat down and wrote to Lady Hamilton, “The signal has been made that the Enemy’s Combined Fleet are coming out of Port. We have very little wind, so that I have no hopes of seeing them before tomorrow. May the God of Battles crown my endeavours with success”. To his daughter Horatia he wrote a message also. On that same day he was in the mood to send a note across to Admiral Collingwood; “What a beautiful day! Will you be tempted out of your ship? If you will, hoist the Assent and Victory’s pendants”. That was the last occasion on which his friend was to receive a message in Nelson’s handwriting.

On this morning the Franco-Spanish fleet, numbering thirty-three ships-of-the-line (battleships in modern phraseology), had, by the orders of Napoleon, put to sea. At first they sailed south, but on the morning of October 21 Villeneuve turned north, so as to get Cadiz under his lee. We are now on the eve of that engagement which took place west of Cape Trafalgar, and in waters that had been famous for British seamen’s exploits ever since the days of Elizabeth. As Cadiz had been to Drake, so it was to Nelson — the enemy’s harbour. Admiral Villeneuve, as he began emerging with a light northerly air at 7 a.m., well knew from what he had experienced at the battle of the Nile that this second meeting with Nelson would be no more pleasant than the first.

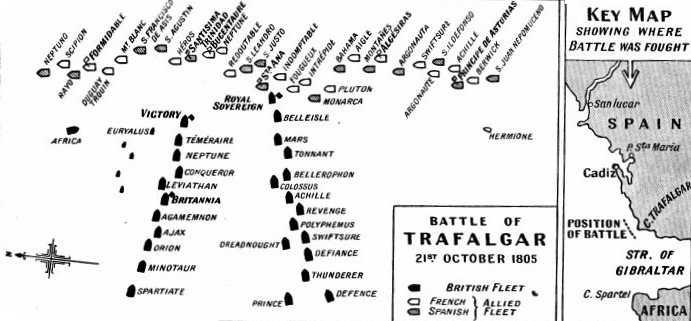

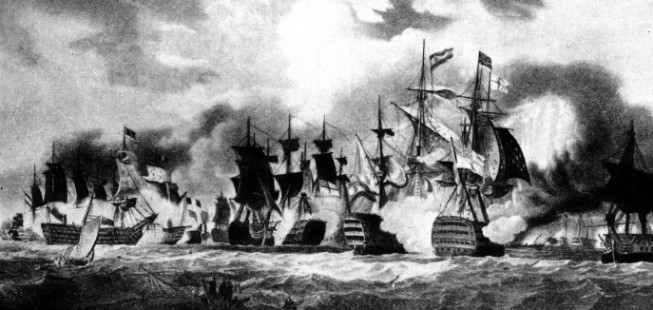

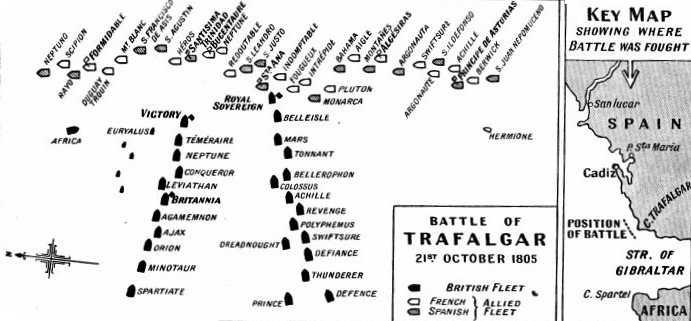

THE APPROACH OF THE FLEETS at noon on October 21, 3805. The British fleet was in two columns, headed by Nelson in H.M.S. Victory and by Collingwood in H.M.S. Royal Sovereign. Collingwood’s column engaged the enemy about twenty-five minutes before H.M.S. Victory broke through astern of Villeneuve’s flagship, the Bucentaure. The Victory was subjected to heavy fire, and Nelson received a fatal wound. After about four hours the enemy began to surrender or retreat. Nineteen out of thirty-three enemy ships-of-the-line were captured.

Fortunately in those slow-moving days officers had more time for recording incidents, so we are lucky to have a mental picture written down by the Captain Henry Blackwood who had called on Nelson at Merton. One of the frigates detached for keeping an eye on Cadiz was H.M.S. Euryalus, and she was under Captain Blackwood’s command. Writing on that day to his wife, he says, “At this moment the Enemy are coming out, and as if determined to have a fair fight; all night they have been making signals, and the morning showed them to us getting under sail. They have thirty-four [sic] sail of the line and five Frigates. Nelson, I am sorry to say, has but twenty-seven sail of the line with him , the rest are at Gibraltar, getting water. Within two hours, though our Fleet was at sixteen leagues off, I have let Lord N. know of their coming out, and I have been enabled to send a vessel off to Gibraltar, which will bring Admiral Louis and the ships in there out. At this moment we are within four miles of the Enemy, and talking to Lord Nelson by means of Sir H. Popham’s signals, though so distant, but repeated along by the rest of the Frigates of this Squadron”. Only two years before Captain Sir Home Popham, R.N., had had his “telegraphic” marine vocabulary printed. This was used at Trafalgar not merely by the frigates, as mentioned by Captain Blackwood. Nelson’s historic signal, in twelve hoists: “England expects that every man will do his duty”, was made by this new Popham method.

At midnight of October 19-20 the British fleet, although expectant, had not been formed into any precise order; on October 20 conditions shifted to a south-south-west wind with thick weather, though it cleared in the afternoon. Villeneuve, having sighted his enemy, prepared for action, though Nelson expected the Franco-Spaniards would sail back into harbour before night. As soon as light permitted on October 21, at 5.50 a.m., H.M.S. Achille (one of the “seventy-fours”), signalled the Victory “Have discovered a strange fleet”. Twenty minutes later the Victory made the general signal, “Form the order of sailing in two columns”. The great occasion had begun.

According to an entry in the log of Thomas Atkinson, Master of the Victory, the enemy was to the eastward, distant ten or twelve miles, consisting of thirty-three sail-of-the-line, with three frigates and two brigs. The British fleet bore up, shook out reefs from the topsails, set royals above the t’gallants and also studding-sails, the wind at 8 a.m. being light westerly and the sky clouded.

The Enemy Opens Fire

The interval had now become only nine miles, and the British fleet was steering for the centre of the Franco-Spanish line which stretched from north-north-east to south-southwest.

At 11.30 the enemy opened fire on H.M.S. Royal Sovereign, which was the flagship of Vice-Admiral Collingwood commanding the starboard or lee column; Nelson, with his flag in the Victory, was leading the port column.

Until the beginning of the nineteenth century ships of the Royal Navy were painted with bright yellow sides, blue upper works and broad black strakes at the water-line; but Nelson used to paint his hulls black with a yellow strake along each tier of ports, whose lids were black. This chequer painting survived until after Trafalgar, when white was soon to replace yellow.

The Victory was already forty years old when Nelson took her into action, a length of service we should now consider impossible for any first-class fighting ship. When built in 1765, she was fitted on her mizen with that old-fashioned lateen yard which had been handed down from Elizabethan days and derived from the medieval galley. The Victory, of 2,162 tons, a three decked 100-guns ship, was the full expression of the sailing vessel able to lie in line of battle, and from the time of her launch down to the end of the eighteenth century most of the British merchant men were of about 300 tons only.

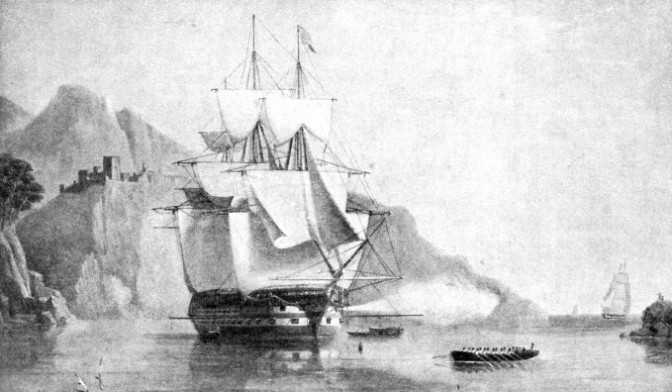

A FRIGATE OF THE ROYAL NAVY during the time of Nelson and the battle of Trafalgar. H.M.S. Hydra distinguished herself on many occasions, such as when she captured the Confiante off Brest, France, on May 30-31, 1798. She also captured the Furet off Cadiz on February 27, 1806. At Trafalgar Nelson’s lighter units included four frigates.

The great warships of this period frequently caused their officers anxious moments. Unhandiness except in a hard wind was a great enough trial, but it is difficult to imagine the feelings of an admiral commanding thirty-three such unwieldy vessels. When Villeneuve realized that an action was imminent, and signalled his ships to form the prearranged order of battle, the Allied fleet was in some difficulty. The ships had been heading south on the starboard tack but, when they were told to wear together and sail in close order on the port tack, the wind remained so scant and the Atlantic swell so pronounced that these vessels could scarcely be coaxed round.

For some while they were without steerage-way, so that the evolution was not completed till 10 a.m.; and even then Villeneuve’s fleet on the port tack did not form a regular line. In the words of Admiral Collingwood, it was in the shape of “a crescent, convexing to leeward, so that in leading down to the centre I had both their van and rear abaft the beam”.

Villeneuve had decided that if the British fleet were to windward, the Allied fleet would receive the attack in close line-of-battle. Remembering all too well Nelson’s tactics in Aboukir Bay, Villeneuve with reason prophesied that the British Commander-in-Chief would “endeavour to turn our rear, to pass through our line, and such of our ships as he might succeed in cutting off, would endeavour to surround and reduce with groups of his own”. Collingwood afterwards reported that the enemy’s line — comprising eighteen French and fifteen Spanish ships — had been formed “with great closeness and correctness”.

Both the French and British Commanders-in-Chief acted much as either had expected. Villeneuve stated, after the engagement, that Nelson had concentrated on the Allied rear “with the double intention of fighting to advantage and of cutting the Allied fleet’s retreat to Cadiz”. This corresponds with the statement in Nelson’s Memorandum, “The divisions of the British Fleet will be brought nearly within gunshot of the Enemy’s centre. The signal will most probably then be made for the Lee Line to bear up together; to set all their sails, even steering sails, in order to get as quickly as possible to the Enemy’s Line, and to cut through, beginning from the twelfth ship from the Enemy’s rear”.

Villeneuve's Line Broken

The British fleet seemed to bring the wind along with it under a cloud of canvas, but the two columns did not maintain that rigid formation which is possible to-day with ships having engines and revolution-indicators. Because of the difference in hull design, trim and foulness of hulls below water, and because of the nature of the breeze, Nelson’s vessels were not in perfect parallel columns. Of the twenty-seven units fit to lie in battle, the Victory, Royal Sovereign and Britannia were 100-guns ships, the rest consisting of four “ninety-eights”, one “eighty”, sixteen “seventy-fours”, and three “sixty-fours”. His lighter units were made up by four frigates and two small craft. The French fleet consisted of four “eighties”, and fourteen “seventy-fours”; the Spanish fleet was made up of the large 130-guns Santisima Trinidad, the two ships Principe de Asturias and Santa Ana, either mounting 112 guns, the 100-guns Rayo, and two ships of eighty guns, eight of seventy-four, and one of sixty-four. There were also five frigates and two brigs.

The action began at noon. Nelson in the Victory leading the northern (weather, or van) column, and Collingwood in the Royal Sovereign, leading the starboard or lee column, broke through the enemy’s line. Nelson made his penetration at about the tenth enemy’s ship from the Allied van. Collingwood broke through farther down the line,, thus closely adhering to Nelson’s Memorandum, leaving Villeneuve’s van cut off and unsupported. The succeeding British units broke through astern of their leaders and engaged the enemy at close range. Collingwood cut off fifteen of the enemy, since three of them were to leeward of the line.

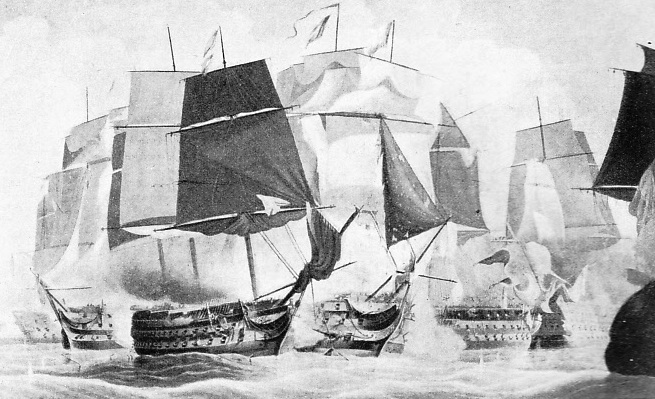

BREAKING THROUGH THE ENEMY’S LINE. This vivid illustration shows Nelson’s flagship, H.M.S. Victory, as she came up between the Bucentaure and the Redoutable (left). Astern of the Redoutable are H.M.S. Temeraire and the French 74-guns ship Fougueux. To the right of the Bucentaure are the Santisima Trinidad and the French 80-guns ship Neptune.

It was not till twenty-five minutes after the Royal Sovereign had begun that the Victory’s column engaged the centre, a feint having been made of attacking Villeneuve’s van. After having borne away to port, and then to starboard, Nelson passed down the enemy’s line and broke through it astern of the Bucentaure, which was Villeneuve’s flagship and the eleventh from the van. Nelson had accordingly fulfilled his specified intention. “My Line would lead through about their centre”. How accurately Villeneuve had read his opponent’s mind is to be noted by Nelson hoisting the signal, “I intend to pass or go through the enemy’s line to prevent them getting into Cadiz”. This was answered at 11.40 a.m. by the Royal Sovereign, and eight minutes later came the Victory’s historic signal: “England expects that every man will do his duty”. No further orders were necessary until 12.15 p.m. when the general signal “Engage the enemy more closely”, was made. Nelson must have remembered Pitt’s words, “It is annihilation that the country wants”.

The first five ships in Nelson’s column were the Victory, Temeraire, Neptune, Conqueror and Leviathan. The Victory was only slightly ahead of the next two, the fourth and fifth were close astern. In his journal Collingwood wrote that the Royal Sovereign, after having opened fire on the twelfth, thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth ships from the enemy’s rear, altered course to port at 12.15. In passing close under the stern of the Spanish three-decker Santa Ana, wearing a Vice-Admiral’s flag (Don Ignatius Maria de Alava), he raked her, then sheered up on her starboard quarter and began a close action in obedience to Nelson’s signal. At this time the British Belleisle, Mars and Tonnant had just broken through the enemy's line and were beginning to engage warmly; but then the smoke became so thick that it was impossible for the British admirals to exercise further direction, and the Captains acted independently in a general melee. The fighting resolved itself into a conflict at such close range that in some instances the rival guns were almost muzzle to muzzle. This incessant fire continued for about three hours until many of the ships had struck their colours and their line had crumpled up.

Assault on the “Victory”

When the Royal Sovereign had been steered sharp round Admiral Alava’s stern and luffed up nearer the wind, Collingwood had been able to pour into the Santa Ana the whole of a broadside, and this terrific concentration of every gun on the Royal Sovereign’s port side almost disabled the Santa Ana. It was because Collingwood’s flagship was the fastest sailer in the division that some minutes elapsed before other units followed this British admiral.

Then, as the Victory approached the enemy’s line, every enemy gun which could bear on the British Commander in-Chief’s flagship opened a terrible fire, striking down many of the crew and doing considerable injury to the Victory’s rigging. But, for the present, Nelson withheld his fire: he and his officers were searching the line for Villeneuve’s flagship, against which a great assault was to be made. At first the task of identification was not easy, for Villeneuve had not hoisted his flag; but Nelson inferred that the Bucentaure (just astern of the huge Santisima Trinidad) was the vessel he looked for and carried his old enemy of Aboukir Bay. And Nelson was right.

The few minutes of suspense, caused by the weakness in the breeze, was impressive both for him and for Villeneuve. During this approach Nelson’s secretary was killed while speaking to Captain Hardy, and Hardy had another narrow escape as a shot passed between himself and Nelson. Splinters were scattered about, and one tore the buckle from Hardy’s shoe. Altogether the ship lost fifty men killed and wounded before reaching the opposing line, after having been under fire during fifteen exciting minutes.

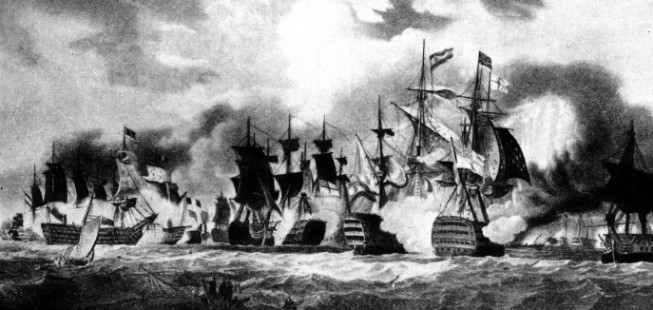

THE THICK OF THE FIGHT. On the extreme right is Villeneuve’s flagship, the Bucentaure. Between her and H.M.S. Victory is seen the Achille, blowing up (in the background). H.M.S. Victory is engaging the Santisima Trinidad and (on her left) H.M.S. Temeraire is engaging a Spanish and a French vessel. On the extreme left is seen H.M.S. Royal Sovereign, with only her foremast standing, engaging the Santa Ana.

But now came the moment when disciplined patience was no longer demanded. In much the same manner as Collingwood had rounded up alongside Vice-Admiral Alava, Nelson passed under the stern of Villeneuve’s flagship, firing every gun of the port side into the Bucentaure, so that a like result was obtained. By this single attack the Bucentaure immediately became little short of a wreck. Twenty of her eighty guns were dismounted and 400 of her crew struck down. On the opposite hand was the French Redoutable, which was engaged by the Victory’s starboard guns.

The climax of the battle was fast approaching and the Allies’ line was a series of ships hurled into confusion. The rest of Nelson’s column (after the manner of Collingwood’s) chose their individual opponents and lay alongside them. A series of desperate duels ensued. Thus from now onwards the Battle of Trafalgar became devoid of tactical value, and the decision rested largely on personal gallantry.

About an hour after the Victory had opened fire and had begun her fierce tussle with a ship on either side of her there entered into the matter that odd factor of luck. Up in the tops of the Redoutable were musketeers who looked down from a vantage point not only on to their own deck, but also on to that of the Victory, close alongside. They could see men toiling at guns and officers at their respective duties.

These snipers watched Nelson and Captain Hardy rapidly pacing the quarter-deck. Hardy was slightly ahead of his admiral when he suddenly turned round and saw some sailors lifting from the deck a short figure conspicuous by the stars on the breast of his uniform coat. It was the gallant Nelson, who had just been struck by a musket-ball from the Frenchman’s mizen-top.

Nelson had a strange foreboding that this battle would be the end of him, and some time before had made a remark to that effect; and now he said to his faithful Hardy, “They have done for me at last”. “I hope not”, came the answer, but the brave little admiral knew better. “Yes”, he insisted, “ my backbone is shot through”. As the sailors were carrying him in great pain below to the cockpit, he still thought primarily of his ship his men and his fleet It would never do to cast a doom over his people and let them become disheartened. His eagle eye noticed that the tiller ropes had been shot away, and he sent a message for Hardy to have these replaced. With his handkerchief over his face and stars to hide his identity, he was brought below, where already many of his men lay suffering and awaiting their turn at the surgeon's hands; but they recognized their beloved admiral and insisted that he should first receive attention. Another crowd of sufferers was brought in a few minutes later from the upper deck.

Nelson's Last Moments

So to the great drama being enacted above, there was now added that personal and poignant tragedy being enacted below deck. At times the issue of the battle hung in suspense. Every broadside discharged from the Victory’s hull made the ship shake till even Nelson’s brave body could scarcely endure the added pain. Frenchmen, Spaniards and Britons were all contending to the utmost of their powers. Although the Santa Ana had been ruined by the first broad-side of Collingwood, Admiral Alava (himself badly wounded) did not yield till her starboard side was crushed in and all her masts had gone. At length, after two terrible hours, he lowered his colours and surrendered At the time it was believed that his injuries were mortal, yet he survived.

But Villeneuve's flagship had struck, too. She never recovered from the broadside which the Victory had given her, and the Neptune and the Conqueror carried away her masts to complete the devastation. Amid all these happenings Captain Hardy’s duties kept him on deck, but in answer to Nelson's repeated messages Hardy descended with the news that at least a dozen of the enemy had surrendered, and that although others (hitherto unattacked) were bearing down upon the Victory, he had summoned some British ships for support and was confident of the result. Again anxious chiefly about his own fleet. Nelson asked. “I hope none of our ships has struck?” And after Hardy had reassured the dying leader, Nelson now thought of himself. “I am going fast, Hardy”, he said; “it will be all over with me soon”. He entrusted Hardy with affectionate messages to his friends in England, and then the anxious Captain, heavy with his sorrow, rushed back on deck amid the din and flash of battle.

HORATIO NELSON was born on September 29, 1758. He entered the Navy in 1770 and became captain in 1779 after having served in the West and East Indies, as well as in an Arctic expedition. In 1793 he commanded H.M.S. Agamemnon in the Mediterranean where he displayed great gallantry during the next four years. In 1797 he became a rear-admiral and was knighted. After the battle of the Nile, Nelson was given a peerage. At the triumphal moment of his career the victory of Trafalgar, he was mortally wounded on October 21, 1805.

The responsibility for the fleet now devolved upon Hardy. Collingwood’s flagship had become out of control by the loss of two masts, so that she was being towed by Captain Blackwood in H.M.S. Euryalus. It was a serious situation for both flagships to be simultaneously in jeopardy, but the succour which the Victory so badly needed came with the arrival of six ships, led by the Royal Sovereign, whose guns were still able to make themselves felt.

The last stages of the battle almost coincided with the final moments of the British Commander-in-Chief. At the time when Nelson's spirit was about to depart, the enemy were preparing to flee. The mortally wounded Spanish Admiral Gravina in the Principe de Asturias, whose place was at the extreme southern end of the line, now with ten ships joined the Allies’ frigates to leeward and made off towards Cadiz.

The five headmost ships of the Allies’ van tacked and stood off to the southward, passing on the windward side of the British fleet. The British tried to thwart them and captured the stern-most, but others got away. Rear-Admiral Dumanoir, with four French ships, also began to retreat. Between 4 and 5 p.m. another French ship. Achille, having got on fire, blew up. Then followed a cessation of cannonading and a strange impressive silence that may be compared with that at the close of the Aboukir Bay battle. Those who stood by Nelson’s scarcely breathing figure told him that the battle was over and that victory had come at last. It is one of the world’s ironies that he should have died in the hour of the triumph which he had so much desired. “I have done my duty, and I praise God for it”, they heard him assert. At 4.30 p.m. his spirit fled.

No fewer than nineteen of the enemy’s thirty-three ships-of-the-line including the Santissima Trinidad, the Santa Ana and the Bucentaure (all flagships), with Vice-Admiral Villeneuve. Vice

Admiral de Alava and Rear-Admiral Cisneros, had been captured.

After Nelson’s death and the end of the battle, Captain Hardy went across to make his report to Collingwood, who had shifted his flag from the Royal Sovereign to the Euryalus. The whole fleet was now in what Collingwood considered “a very perilous position, many dismasted, all shattered, in thirteen-fathom water off the shoals of Trafalgar”. For the westerly wind during the hours of hostilities had set the two fleets eastwards till they were only eight miles from Cape Trafalgar.

Enemy Fleet Annihilated

In these circumstances the least desirable event would be an onshore gale, yet that is exactly what ensued. But the wind shifted a few points during the night and the danger was averted.

It was a keen disappointment that out of the nineteen prizes, one was accidentally burnt and that fourteen foundered or were recaptured, wrecked or destroyed, thus leaving one French and three Spanish ships to be sent to England. Their disabled condition made them of little ultimate value. Perhaps the greatest material reversal of circumstance after triumph consisted of the foundering of the French Redoutable, the stranding of the Bucentaure on the rocks and the recapture by the French of the Santa Ana.

Collingwood wrote home to his wife, “Our prizes you see are lost, but was there ever so complete a break-up of an enemy’s fleet? If we have not saved them to ourselves, we have at least put them out of the power of doing any further mischief”. From now on Napoleon despaired of his own navy, or of ever rivalling the British at sea. In the hour of Nelson’s death Bonaparte received from the sea such a rebuff that he never quite recovered.

The death of Nelson marks the end of the era of the logical development of Tudor naval thought. The age of steam and steel, the scientific study of naval warfare in all its applications, were to transform the Service during the nineteenth century, and after, so thoroughly that had Nelson been brought back to life on board a modern battleship, or gone below in a submarine to be shown a torpedo, he would have become as utterly bewildered as any eighteenth century landsman on board the Victory. His tactics at Trafalgar have been, during our own generation, criticized as “a mad, perpendicular attack, in which every recognized tactical card was in the enemy’s hand”; and “the risk he took of having the heads of two columns isolated by a loss of wind or crushed prematurely by the concentration to which he exposed them naked, almost passed the limits of sober leading. Its justification was its success”.

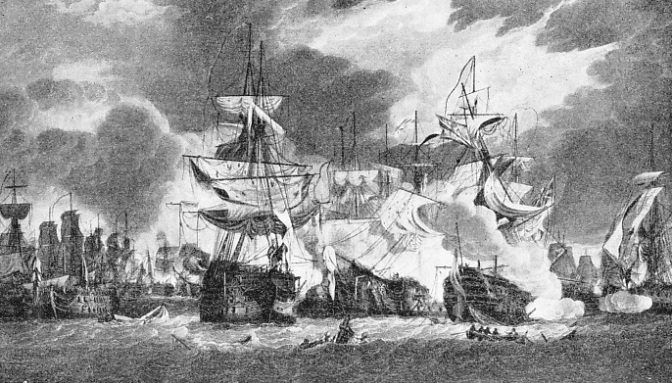

AFTER THE ACTION AT TRAFALGAR there was a strange and impressive silence. Every ship was badly damaged, and, to make matters worse, during the engagement a westerly wind had driven the opposing fleets to within eight miles of Cape Trafalgar. Fortunately the wind changed before the ships drifted ashore, although four dismasted enemy ships had to ride the storm at anchor close to the shore.

You can read more on “Battle of the Nile”, “Decisive Naval Actions” and “The World’s Most Famous Ship” on this website.