© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Ships’ Figureheads

From the earliest times the stems of vessels have been decorated with some form of figurehead. Such adornments have fallen out of general use, but until comparatively recently the seaman attached great importance to the figurehead of his ship

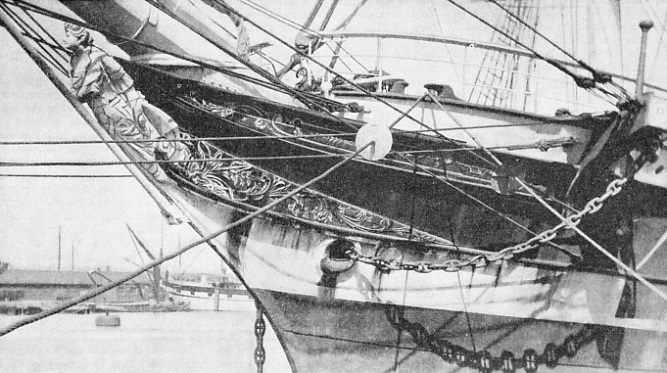

THE GRACEFUL STEM and figurehead of the Port Jackson, a four-

286 ft 3-

SHIPS’ figureheads are something of a craze. There are many people who delight in the picturesque features of figureheads and their connexion with the past, but few realize how much they meant to the old-

In 1778, the Channel Fleet, finding itself helpless against the French through incompetence and corruption at the Admiralty, was in full retreat before a force that it could apparently have beaten. A boatswain’s mate in the Royal George slipped over her bows carrying on his arm his hammock, which he lashed over the eyes of the figurehead representing King George II, a courageous monarch. In answer to an officer on the forecastle head he replied, “We ain’t ordered to break the old boy’s heart, are we? I’m sure that if he was to turn and see this day’s work, not all the patience in heaven would hold him a minute.”

At a time when the least insubordination in the Fleet was punished by the cat-

It was a wise captain who knew when to tauten up his men by referring to the figurehead, but it required courage for a frigate captain to make this speech in the late eighteenth century: “Now, I tell you what it is, my lads. Unless you are off those yards and the sails are hoisted again before any ship in the squadron, by the Lord Harry, I’ll paint the figurehead black!” The threat gave his ship the best time in the exercises. Then there is the incident recorded by Captain Marryat in Peter Simple, one founded on fact, as were most of his novels, when the crew of the Rattlesnake, disgusted with the cowardly retreat of Captain Hawkins, cut off the figurehead of the serpent with its fangs.

Not only had the figurehead a sentimental significance for the crew, but it was also an object of superstition. HMS Atlas, a fine three-

The enthusiasm of the sailor was apt to outrun art, both in the design of the figurehead and in its colouring. To the student this only serves to increase the human interest, although to those who do not know the circumstances the work may seem merely garish. Scroll work and “fiddle” or “billet” heads -

The origin of the figurehead is one of the many nautical mysteries, but it goes back far into the past. It seems to have been founded in a mixed desire to conciliate a deity and to terrify an enemy; the idea of decoration probably came far later.

Probably the earliest known form of figurehead is found in the prehistoric ship of ancient Egypt. The ends of Egyptian ships came up in a graceful curve, taking the form of a lotus stem -

For a period in the Middle Ages the figurehead was eclipsed, as the necessity for every ship to be able to fight and the fitting of the forecastle platform left no room for the figure to rear itself proudly as it did in the long ships. Where it could be fitted at all it took the form of a rather mean serpent’s head or similar object placed under the platform. More often the desire for decoration had to be satisfied by the use of hull paint and by the shields (pavises) of the knights who were fighting on board. Later wooden reproductions of the shields called pavisades were placed in permanent position round the rail and satisfied the desire for decoration.

Curiously enough, the tradition of the figurehead does not appear to have been affected in the least by this period of suppression. This shows the hold the figurehead had over the seamen’s minds, for there was no reading and little or no illustration to keep it alive. As soon as the development in ship design superseded the old built-

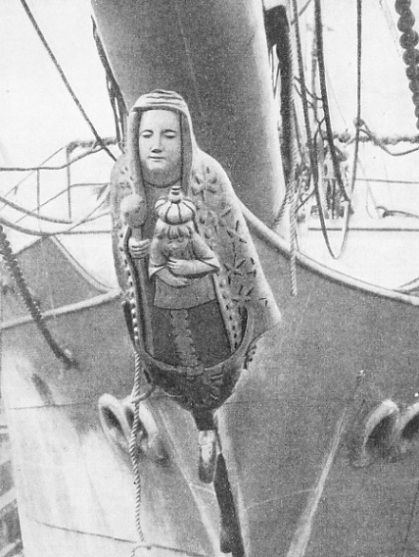

SPANISH FIGUREHEADS were often elaborate and of a religious nature. This photograph shows the figurehead of the Ama Begonakla, built on the Clyde in 1902 for Spanish owners, and registered at Montevideo, Uruguay. A four-

In the reign of Henry VIII the lion became the general British figurehead, and, with few exceptions, remained popular until the end of George II’s reign. It was borne by such famous ships as the Great Harry, Elizabeth’s Victory and Sir Richard Grenville’s Revenge, in the early days of the beak bow. In these vessels the figurehead took the form of a heraldic lion couchant or gardant. When he ascended the English throne James I introduced the Scottish lion rampant, with a Royal Crown. Cromwell eliminated the Crown, but Charles II restored it. He began also the custom of varying the figurehead for all first-

By Stuart days the beak head had become modified, breaking away from the galley tradition, so that the lion rampant at the end of a false stem gracefully curved became part of what was known as “the sweep of the lion”. The decorated trail boards were given an elegant curve that remained unaltered for many years, even if it was far less suitable for many of the heads which were later fitted to it arid had a tendency to put them into a strained attitude. Some prominent exceptions to this lion figurehead are worth noting. James I’s ship the Royal Prince, built in 1610, had a figurehead of Prince Henry, which was regarded as a pleasing innovation. The Sovereign of the Seas of 1637, the most famous fighting ship of her day, whose decoration had accounted for one-

The rich decoration of this ship had such a hold on popular fancy that even Cromwell was unable to enforce his order that all ships of the Navy should be painted a “sombre black”. He had to leave her in her original state. She earned the nickname of “The Golden Devil” from her Dutch enemies. Cromwell’s order cut down the decoration of hulls and sterns, but he appreciated the value of the figurehead and copied the scheme of the Sovereign of the Seas when he built the Naseby. King Edgar’s figure on the horse was replaced by Cromwell’s figure trampling on the fighting men of six nations. Other Commonwealth ships were given somewhat similar heads, but after the Restoration these were cut off and sold as firewood, being ceremoniously burned on Coronation night.

To judge from contemporary prints, and from the example preserved in Holland as a relic of the Medway raid, these seventeenth-

In the mid-

In the smaller types, fiddle and scroll heads were generally considered sufficient in official circles, but their captains often went to the expense of replacing them with something more decorative and inspiring. The heads of French ships were generally more artistic and appropriate than the British. The Spaniards were noted for wonderful and elaborate groups of religious figures.

In the eighteenth century the Admiralty made several efforts to abolish the figurehead because of its cost. In this it failed, but much was done by pointing out to the common sense of the sailor that a heavy figurehead projecting over the bow of a sailing ship was a serious handicap to her sailing qualities. To lighten it without impairing its sentimental value, the figurehead was frequently carved out of soft wood, which gave it a much shorter life and robbed us of many examples. Similarly, the Admiralty attempted to restrict the colours to gilt or white, but since the bluejacket preferred something in more than natural colours, the authorities were tactful and often turned a blind eye.

THE CURVED STEM OF AN IRON SHIP often offered better opportunities for the addition of a figurehead than did the stem of a wooden vessel. One of the most graceful figureheads of recent years was that carried by the Swedish ship Beatrice, formerly the British Routenburn. She was engaged in the Australian grain trade and was broken up in 1932-

It was during the French wars between the middle of the eighteenth century and the fail of Napoleon that the figurehead attained its greatest sentimental height. The whole fleet at Trafalgar noted the fact that King George III led his ships into action as the figurehead of Collingwood’s flagship, the Royal Sovereign. It was regarded as an excellent omen when she got into action before the Victory. When the famous Captain Death built his privateer, the Terrible, perhaps the best known under the British flag, he selected a skeleton as the figurehead. Surcouf’s French corsair Revenant carried a corpse. The original figurehead of the Victory may be seen to-

Not all the figureheads made such an appeal, and many ships were cursed with figures of purely political interest. The British Navy did not alone suffer, as witness the history of the United States frigate Constitution. This vessel has a similar sentimental interest for Americans as the Victory has for us, and is affectionately nicknamed “Old Ironsides”.

Her figurehead was originally that of Hercules, signifying the strength of the union and the power of the law. In 1807 it was changed for one of Neptune, and during the war of 1812, when the ship won her proudest bays, she had a billet head only. In 1833, during Andrew Jackson’s candidature for the Presidency, his portrait was fitted into the old ship as a figurehead, but so great was the outcry against it and so threatening the situation that a special guard was placed over it. The malcontents, however, contrived to saw the head off one night and make off with it. The 1,000-

Specialist Carvers

The abolition of the beak bow after Trafalgar, where many casualties were caused by its faults, reduced the opportunity of the figurehead and it became much simpler, especially in its trail boards and supports; but the interest was taken up by the Merchant Service. Until the end of the Napoleonic wars East and West Indiamen carried figureheads, but few other merchant ships had more than a scroll or fiddle. With postwar improvement at sea, more attention was paid to the external features of ships, especially those which had a public appeal. The fine lines and long swan bows of the clippers gave a good opportunity, and every advantage was taken of them.

There was far wider variety of choice with merchantmen than with men-

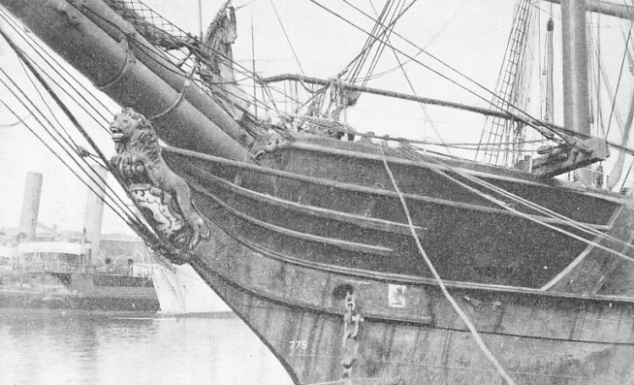

A CREST AND FIGUREHEAD OF A LION RAMPANT adorned the wool clipper Cimba, a full-

The clipper Styx had a full-

All Corsar’s ships had the flying horse, which was appropriate in the Pegasus only. Many shipowners installed their own portrait or that of one of their family. With the Norman Court that was justified, for the young member of Thomas Baring’s family, who was honoured, was a beautiful and graceful girl to whom the carver did full justice. But when an owner decided to honour Samuel Plimsoll, the sailor’s friend, in the ship named after him, and when Mr. Bates christened a vessel the Bates Family and decorated her accordingly, the effect was less happy.

Continental owners were particularly fond of figureheads of themselves or of their business friends in frock coats and top hats, with incongruous results. There were many British examples of this also. When James Baines, owner of the Black Ball Line of clippers, ordered the ship James Baines of Donald Mackay of Boston, he insisted on his own figure being carved. As he was a redheaded, snub-

AFTER TRAFALGAR, in 1805, the French warship Duguay Trouin was captured by the British and renamed HMS Implacable. Her figurehead was in keeping with her new name. Immediately below the bust may be seen the “fiddle”, a decoration that had to suffice for many ships. A similar decoration executed in the opposite direction would be known as a “scroll”.

Donald Mackay, as befitted a man whose life was wrapped up in the ships which he built, was far more particular over the figure-

While the figureheads of merchant ships were being developed and were attaining a high standard, it was proving increasingly difficult to retain them in men-

The latter days of the nineteenth century saw the clipper stem disappear in warships and in nearly all merchantmen. With it went the figurehead. Some efforts have been made to restore it or to find a substitute. When the US battleship Massachusetts was built in the ‘nineties the State of that name presented her with a fine figure of Victory in relief, which was fixed between the thirteen-

Nowadays the figurehead is almost confined to the few surviving sailing ships, still fewer clipper-

It is the old examples, however, which are treasured. In the Scilly Isles there are many figureheads taken from ships that have come to grief there, although many of them have rotted and disappeared. A well-

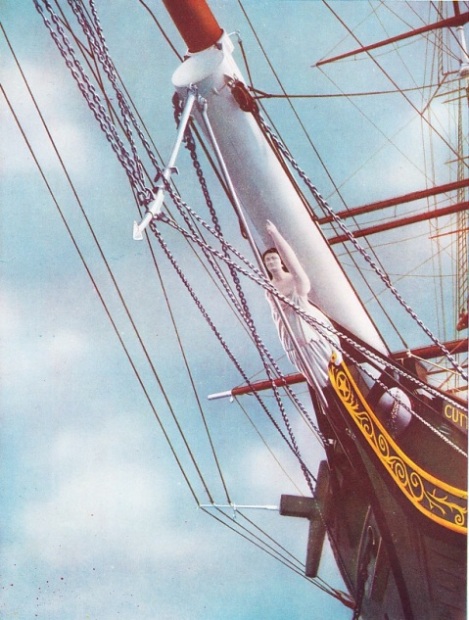

THE FIGUREHEAD OF THE FAMOUS CUTTY SARK represents the figure of Nanny the Witch. A contemporary ship, the Tweed, belonging to the same owner, had a figurehead of Tam o’ Shanter. For some years the Cutty Sark has been preserved in Falmouth Harbour, Cornwall. A clipper ship with a displacement of 1,970 tons and a gross tonnage of 963, the Cutty Sark had an iron frame planked with wood. She was launched at Dumbarton on the Clyde in 1870 for Captain John Willis. In 1875-

You can read more on “In the Sailing Ship’s Forecastle”, “Last of the Giants” and

“Romance of the Racing Clippers” on this website.