| Binding |

| Cookie Policy |

| Donate |

| FAQs |

| Illustrations |

| Links |

| More on Shipping Wonders |

| Other Series |

| Privacy Policy & Terms of Use |

| List of Illustrations |

| Ship Illustrations |

| Part 1 |

| Part 2 |

| Part 3 |

| Part 4 |

| Part 5 |

| Part 6 |

| Part 7 |

| Part 8 |

| Part 9 |

| Part 10 |

| Part 11 |

| Part 12 |

| Part 13 |

| Part 14 |

| Part 15 |

| Part 16 |

| Part 17 |

| Part 18 |

| Part 19 |

| Part 20 |

| Part 21 |

| Part 22 |

| Part 23 |

| Part 24 |

| Part 25 |

| Part 26 |

© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The “Great Republic”

Although she did not achieve the success which was expected of her, the “Great Republic” is generally regarded as the masterpiece of her famous builder, Donald McKay

THE name of the Great Republic, the biggest sailing ship of her time, is always linked with that of Donald McKay in a way that absolves him from blame for her comparative failure and pays tribute to his courage in building such a ship.

THE name of the Great Republic, the biggest sailing ship of her time, is always linked with that of Donald McKay in a way that absolves him from blame for her comparative failure and pays tribute to his courage in building such a ship.

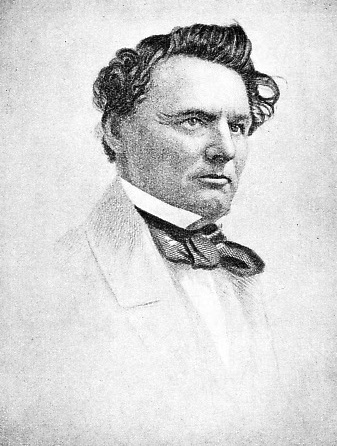

DONALD McKAY, ONE OF THE GREATEST BUILDERS OF CLIPPER SHIPS. It was his ambition to build the biggest clipper ship that the world had ever seen, and it is no reflection on his skill that the Great Republic was a comparative failure. Despite McKay’s fine reputation and long succession of first-

His reasons for doing so were threefold. First there was the desire for greater carrying economy which a bigger vessel would give, for seamen were becoming increasingly expensive and the more cargo that could be carried in one bottom, the less the cost per ton. Secondly there was his personal pride, of which he made no secret. He was in the front rank of clippership designers and builders, although in his lifetime he did not stand alone as his memory does to-

Across the Atlantic British builders were beginning to show wonderful results from iron hulls, and unless they were checked by worthy competition the American industry, even with its advantage of unlimited natural material, would be ruined.

When he designed the Great Republic McKay had British trade in mind for her to cover, as she was entitled to do since the repeal of the Navigation Act in 1849. Gold had been discovered in Australia and the long voyage out with emigrants reproduced to an extent the difficulties of the American inter-

The Great Republic was designed for a registered tonnage of 4,555 on a length of 335 feet, a beam of 53 feet, and a depth of 38 feet. She had four decks, the uppermost (spar) deck being flush with the covering board in a manner later made familiar with steamers, but novel then with sailing vessels. Her hull was built with immense strength, obviously necessary if such a length were to be driven through heavy seas with only a wooden backbone, and a good deal of iron latticework was embodied in it. To reduce the number of men as much as possible the most economical rig had to be given her and that of a four-

McKay was anxious to have the ship launched on his forty-

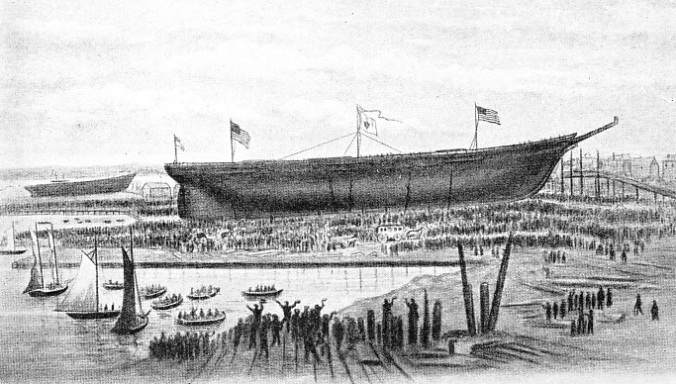

LAUNCH OF THE GREAT REPUBLIC at Donald McKay’s shipyard, Boston, USA, on October 4, 1853. It had been McKay’s ambition to have the ship launched on his forty-

The Great Republic took the water as McKay’s own property and was built without a cent having been borrowed on bottomry (eg. a system of lending money to shipowner for purposes of voyage on security of ship, lender losing the money if the ship is lost.) He had no intention of being a shipowner, but when none of his clients would consider such a big ship he determined to run her himself on the Australian trade. His brother, Captain Lauchlan McKay, who had made a high reputation as master of the Sovereign of the Seas, was put in command and became as enthusiastic as her owner. The tug R. B. Forbes, named after the ingenious captain who had invented her double topsails, was sent round to Boston to tow her to New York. Captain Forbes persuaded McKay to take advantage of the interest that she created to make a small charge for the privilege of inspecting her, the sum to go to establishing the projected “Snug Harbour” for aged seamen in Boston. The idea was a great success; thousands flocked to see the wonder ship as part of their Christmas entertainment in New York, and the “Snug Harbour” received enough money to start operations. But that was an end to the luck of the great vessel.

Destroyed By Fire

She was lying alongside the quay and had almost completed her loading with a general cargo, mostly provisions for Liverpool, preparatory to carrying emigrants out to Australia, when a spark from a fire ashore set light to her rigging and in a short time she was a blazing mass aloft. The fire engines of that day were powerless to throw their jets to the top of her lofty masts, and as the burning spars fell they set light to her deck fittings. Two clipper ships in adjoining berths, the Joseph Walker and the White Squall, were destroyed; the Great Republic lay scuttled at the bottom of the dock, burned down to the water’s edge. As much as £60,000 had been spent in building her and fitting her out; her hull was insured for £36,000, and with freight, McKay received about £47,000 from the underwriters. The financial loss crippled him for some years; the destruction of all his high hopes broke his heart and, although he did some of his best work afterwards, affected him to the end.

McKay abandoned the wreck to the underwriters, who sold what remained. Her cargo was completely spoiled by fire and water, and the raising of such a big hull was by no means an easy matter. A temporary stern was rigged and the hull was frapped in canvas, after which four portable steam pumps cleared the water and brought her to the surface. Captain N. B. Palmer, one of the best-

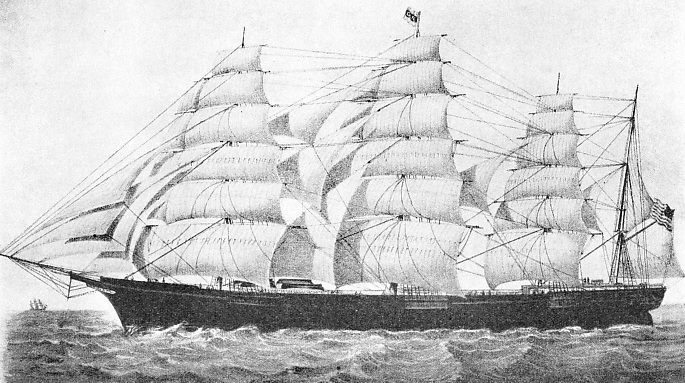

By not replacing her spar deck, her registered tonnage was reduced to 3,357 and her cargo capacity by nearly 2,000 tons, while she was also drastically cut down aloft. Howe’s double topsails replaced those of Forbes’ patent, the 120-

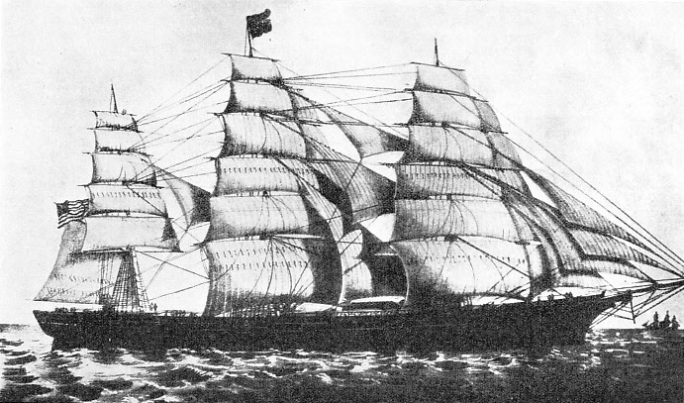

THE GREAT REPUBLIC WAS DESIGNED to have a registered tonnage of 4,555 on a length of 335 feet, a beam of 53 feet, and a depth of 38 feet. She had four decks, the uppermost (spar) deck being flush with the covering board in a manner later common with steamers, but novel in those days with sailing ships.

Under the command of Captain Limeburner she loaded a second cargo in New York, and finally sailed in February, 1855, consigned to W. S. Lindsey & Co, whose principal, the historian of the British Merchant Service, recorded that she was much too big to be profitably employed in ordinary trade. She made the run to Liverpool in nineteen days, behaving as a tall ship should, although she was drawing twenty-

Her first passage was from Liverpool to Marseilles with 1,600 British troops for transhipment into four steamers, to continue the voyage to the Black Sea. The charter rate was 17s. a ton a month, and she remained on this profitable business until the end of the war, when she returned to New York to prepare for an intercoastal cargo.

She sailed from New York in December, 1856, broke the record by crossing the Line in fifteen days eighteen hours from Sandy Hook, and finally, in spite of being delayed for five days by calm and fog off the Californian coast, made San Francisco ninety-

Used By Gold-

Had it not been for her bad luck at the end of the voyage, it is more than probable that she would have lowered the inter-

The carpenters in the islands were well accustomed to big jobs on sailing ships, but they had never tackled anything the size of the Great Republic, and most of the materials had to be specially brought from the mainland. Her provisions, which had to be replaced when the sea water, strongly impregnated with guano, leaked through into the lazarette, were also more than the islanders could provide and had to be brought from the River Plate. It was not until early in 1858 that she reached London, where she again had to transfer part of her cargo into lighters before she could pass over the sill of Victoria Dock.

Back in the United States, she was again put on berth to San Francisco. The West was growing up and demanded from the Eastern States a large number of commodities which were difficult, or impossible, to carry by ordinary ship. The size of the Great Republic enabled her to take bulky freight under deck, and she had a reputation for good delivery of cargo; these factors, with her smart outward passages, and with Captain Limeburner’s name, secured her excellent bookings among the gold seekers. Her passages varied, but were generally in the neighbourhood of 105 to 120 days; homeward she generally sailed in ballast owing to the difficulty of filling her with cargo on the West Coast, but occasionally she ran from San Francisco to Liverpool with grain. She never attempted to beat her fine maiden passage, but her runs were generally creditable.

As in most sailing ships in those days, she was owned in shares, and A. A. Low & Brother & Co. had sold a considerable number, amounting to forty sixty-

THE HULL OF THE GREAT REPUBLIC WAS OF IMMENSE STRENGTH, This was necessary if such a length of ship were to be driven through heavy seas with only a wooden backbone, and a good deal of iron lattice work was embodied in the hull. To reduce the number of men as much as possible, the most economical rig had to be given her, and that of a four-

Abandoned By Her Crew

When Paul returned to New York in 1865, the vessel was laid up for nearly two years, having failed to find an active buyer, although her owners took the greatest care with her fabric and she was visited by thousands of sightseers. In 1866 an enterprising master mariner from Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, Captain J. S. Hatfield, bought her, but was unable to complete, and she was still under Low’s ownership when she was recommissioned in 1868 and did the passage from St. John to Liverpool in fourteen days, one of the fastest passages on record and one that seemed to justify the saying that no steamer could catch her when she had a whole-

In this undignified role she sailed. from Rio in ballast in January, 1872, ordered to St. John, New Brunswick, to load a cargo of lumber, the sailing ship’s last hope, for the United Kingdom. For a long time past she had been giving a good deal of trouble; her huge hull had strained badly, having been driven on the Californian trade, and she had been fitted with two unusually large double-

You can read more on “Hell Ships and Floating Homes”, “In the Sailing Ship’s Forecastle” and

“Last of the Giants” on this website.