The Coastguard Service was brought in 1922 under the control of the Board of Trade and reorganized into two divisions - the Coast Watching Force, concerned with life-saving and the salvage of wreckage, and the Coast Preventive Corps, concerned mainly with the prevention of smuggling

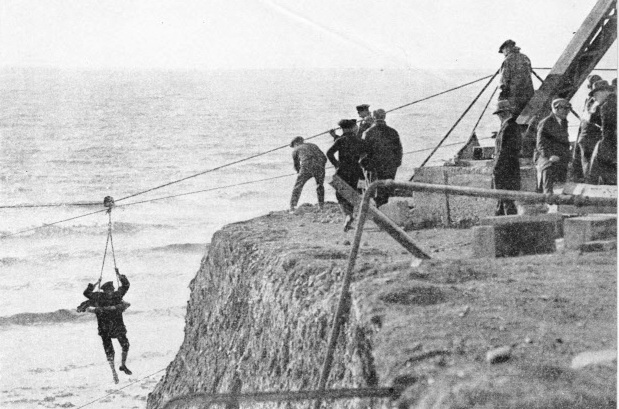

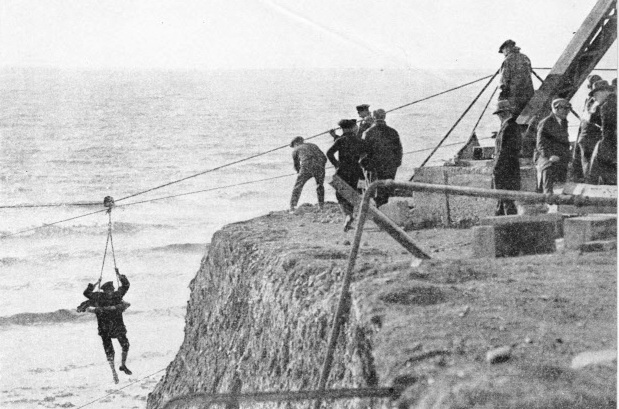

THE BREECHES BUOY IN ACTION. A light line is fired over the vessel from a rocket apparatus and a hawser is thus hauled on board. The breeches buoy then brings the crew ashore one by one. This photograph was taken during the rescue of twenty Italian seamen from their ship, the Nimbo, which had gone on the rocks between Newhaven and Brighton, Sussex.

SINCE the earliest days of her history Great Britain has had some form of coast-watching service, but its constitution and duties have changed from time to time to meet varying requirements. In the olden days wrecks on the coast were plundered for booty often valued at thousands of pounds. Smuggling, however, which is dealt with in the chapter “Smugglers and Revenue Cutters”, was the main cause of the introduction of a coast-watching system.

As soon as the Government of a country imposes taxes on certain imports there rise at once a number of people determined to cheat the Government of its dues and at the same time,

by smuggling, to make a fortune for themselves. The British Isles, with their indented coast-line and long stretches of sparsely populated shore, lend themselves particularly to this form of illicit trade.

As far back as 1698 there existed a recognized coast force consisting chiefly of preventive officers and riding officers who patrolled the coasts. These officers were at a later date augmented by Dragoons, and in 1822 the Army took over the control of the whole of the coast riding force.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Government took more active steps about coast watching and a stronger preventive force was employed, chiefly under the Treasury and Customs Departments. Men with sea training were also required to man patrol vessels and the Admiralty gradually gained some control. A signalling system was organized which, although slow, was fairly efficient and operated between the various watch stations and from hill to hill to London.

The Napoleonic wars led to an increase of smuggling. At this period, too, the threat of invasion, of which the Martello Towers on the south and east coasts are a reminder, led to the personnel of the coast watchers being greatly increased and their duties multiplied.

Peace brought with it much un employment among seamen, many of whom were taken on for coast duties. Gradually the work of coast watching was sorted out, but the control was mixed, the Admiralty, War-Office, Customs, Treasury and Board of Revenue all having an interest. Soon blockade stations were built round the coasts and developed into the well-known Coastguard Stations. A Preventive Water Guard also was formed which was responsible for the Revenue Cutter Service. In 1852, the Admiralty gained more control and became responsible for appointing lieutenants of the Navy as Chief Officers of the various districts into which the country had been divided. The name Coastguard Service was adopted about 1831 and the personnel became Coastguardsmen, though the force remained under the Board of Customs, with a Coastguard Office at the Custom House. A special flag for the service was allotted and retained until 1857.

The Admiralty kept a watchful eye on the service for many reasons, but perhaps the most important reason was that the service formed a useful nucleus of reserves in the event of war. This

reserve was officially recognized in 1845. As far back as 1827 ex-naval men had been called up and had taken part in the battle of Navarino,Greece. In general, however, they had been found too old or unfit for the job.

In 1857, after the Crimean War, the Coastguard Service was placed on a more definite footing under the Admiralty by an Act of Parliament which formally embodied it for “the Defence of the Coasts of the Realm, and the more ready manning of the Navy”. Thus it remained with varying minor changes until the war of 1914-18, when the officers and men of the Coastguard Service did excellent work ashore and afloat.

This Coastguard Service was an occupation much sought after and gave employment not only to pensioners and ex-service-men, but also to active service ratings. It was a satisfactory two-years job for captains awaiting ships and provided further employment for officers who had passed the promotion zone.

During the war of 1914-18 the duties of the Coastguard became increasingly arduous and varied, and required a trained personnel, so that many of the men who had been embarked at the outbreak of war had to be recalled ashore again. The Coastguard rendered valuable services and was ably assisted by civilians, Boy Scouts and Sea Cadet Corps. In 1919, the constitution of the service was examined in the light of war experience, and H.M. Coastguard, hitherto an active service body, was reconstituted on a pension basis.

Strange to say, the question of life-saving from wrecks was not referred to in the Act of Parliament of 1857, though previously the instructions had contained orders for rendering assistance to vessels in distress and saving the lives of persons on board. After the Admiralty had taken over the Coastguard it was clear that it did not responsibility for the inadequacy or otherwise of the life-saving system round the coasts. Coastguardsmen could assist in this work provided it did not interfere with their numerous other duties.

They could help to launch lifeboats, for instance, but were not supposed to go out in them. The lifeboat service was and is run as a Society maintained by public subscription, and private life-saving companies were formed for providing other life-saving apparatus. The Board of Trade eventually took over the supervision of these private companies and added other stations.

On the reorganization of the coast service in 1922, the old Coastguard Service as such ceased to exist, but the word Coastguard was retained, as in war-time the Admiralty would once more take over all coast duties. In peace-time, the Board of Trade is now responsible for H.M. Coastguard, although the Admiralty still maintains purely naval stations.

The Coastguard is now divided into two sections — the Coast Watching Force under the Board of Trade and styled H.M. Coastguard, and the Coast Preventive Corps. The duties of the Coast Watching Force are mainly connected with the saving of life, the salvage of wreckage and the administration of foreshores.

The Coast Preventive Corps, which is supplementary to the Coast Watching Force, performs duties in connexion with the protection of revenue, and, the cost of maintenance is borne by the Customs and Excise Vote. The administrative side of H.M. Coastguard is carried out by a Chief Inspector and Deputy Chief Inspector at the Board of Trade, both officers being retired naval officers.

The coasts of Great Britain and Northern Ireland are divided into twelve divisions, each with an Inspector, who is generally a retired captain or commander of the Navy, in charge. Each division has a varying number of stations in it according to the length and nature of coast to be watched. The North Scotland Division, for instance, has fifty-three stations and the Northern Ireland Division seventeen.

Rocket-Apparatus Stations

The stations vary in the number of personnel and in the watch kept, according not only to their locality, but also to the weather conditions prevailing. In these days of wireless and quick communications the maximum watch is necessary only in bad weather or in such weather as would render boat work difficult.

In the most important stations watch is kept day and night and is taken by four men. Other stations have three or two men according to the circumstances. The staff belongs to the standing force. In addition to these permanently manned stations, there are auxiliary ones in which watch is set only in bad weather, and the personnel is provided by volunteers from among local persons under the charge of a responsible resident. The number of stations occupied exceeds 250, and there are more than 750 watch-keepers. These numbers do not include about sixty auxiliary watching stations and lifesaving apparatus stations where “look-out” is kept in bad weather.

Watch at all the stations is kept from a look-out hut. This is equipped with telephone, flagstaff and signal flags, telescope, binoculars, flashing lamps, foghorns, fog-signals, rockets and megaphones. The look-out is in constant touch with neighbouring life-boat stations, life-saving apparatus, other look-out huts and with the District Officers and Inspectors.

A PISTOL ROCKET APPARATUS was used by the Lowestoft, Suffolk, rocket life-saving crew in 1928 when they rescued eleven men from a Dutch steamer which had gone aground. For this the Lowestoft men were awarded the Board of Trade Shield, for the finest rescue performed during the year. The line is fired over the vessel in distress.

The introduction of the telephone has greatly increased the efficiency of the coast-watching system, as connexion can be made with outlying islands, light-vessels and so on. In some instances, radio-telephony or wireless is available. The Post Office also provides special arrangements for dealing with life-saving messages, which are given priority. The Police Force normally employed at coastal places is specially instructed as to the nature of distress signals at sea, and the officers of H.M. Coastguard Service keep in touch with civilians who are likely to be of assistance when a vessel is in distress. Thus the coast watching services are now organized for life-saving to an extent never known before. On seeing or receiving information of a vessel in distress or in difficulties, it is the duty of H.M. Coastguard to ensure that adequate rescue measures are forthcoming without delay. The distress signal is at once answered so that those on board the vessel may know that assistance is forthcoming, and the appropriate life-saving authorities are informed fully as to the circumstances.

If the distressed vessel is close inshore and the weather bad, the Rocket Apparatus Company, which is under the charge of the Coastguard, is called out. Throughout a particular service, the Coastguard maintains the closest touch with all the authorities concerned with the rescue measures and, if the vessel is in touch by wireless, the Coast Wireless Station receives her signals.

The work of the lifeboat is well known (see the chapter “The Drama of Life-Saving”), but the work of the rocket life-saving apparatus is not so prominent. The lifesaving appliances are mainly in the direct charge of volunteers formed into companies. These various companies form the Coast Life-Saving Corps and embody some 5,000 men. The equipment consists of rockets for carrying lines to a wreck with suitable apparatus for obtaining a “good shot”, an endless rope rove through a block, a hawser and a breeches buoy. The whole apparatus can be stowed in a lorry and transported to a suitable spot as close to the wreck as possible. As there are about 350 rocket apparatus stations, the distance of the wreck from the station is rarely excessive.

The rocket is fired over the vessel requiring succour and carries with it a line. The line is attached to the rope and block and this is made fast on board the vessel. From the shore the hawser is then hauled to the vessel, and after everything has been properly set up, the breeches buoy can be transported to and fro as a passenger service. Instructions for operating the service are printed in four languages and attached to the block so that the crew on the wreck can know what to do; but even if they do not understand, the people ashore can generally help.

Volunteers for this valuable work are taken from all walks of life and receive a retaining fee and an allowance for drills and service rendered. The age limit for volunteers is normally fifty and the retiring age sixty-five. Long-service medals are awarded after twenty years’ service. Every year a shield is awarded for the “most meritorious service” rendered by H.M. Coastguard and the companies of the Coast Life-Saving Corps.

The shield for 1935 was awarded to the Bootle and Whitehaven (Cumberland) Companies for their services in connexion with the steamship Esbo, which drifted ashore early on October 19 in that year. The Bootle men arrived on the scene at 7 a.m., but the vessel was then too far out for the rocket to reach her, and even during the forenoon when the vessel had got inshore, the gale and distance were still too great.

Meanwhile, the District Officer was busy, and the Whitehaven Life-Saving Corps dashed to the rescue with their apparatus in a lorry and, thanks to the aid of the police, covered the thirty miles in less than an hour in spite of the dreadful weather conditions. The lines of the Whitehaven Corps were dry and one reached the wreck about 12.30, but the distance, the fact that the ship was yawing badly, and the boulders on the foreshore made rescue work difficult.

The hawser could not be got out and so the breeches-buoy was attached to the whip, which had to be lengthened because of the rising tide, and greatly added to the difficulties of the rescue. After three hours’ work, all the crew of twenty-four men were saved. It had been a difficult and dangerous job, for the heavy seas were breaking over the ship. One boat, containing nine of the crew, was launched from the Esbo, and would probably have been lost but for the fact that the volunteers dashed into the surf and got the occupants safely ashore.

Although life-saving from shipwrecks may be looked upon as the principal duty of the Coastguard nowadays, because the Customs Officers look after preventive duties, yet there are many other little jobs with which they help whenever possible, such as rescuing people who fall down cliffs or get caught by the tide, and assisting people who get into danger while bathing or boating. The Coastguard Service also has certain responsibilities in connexion with wrecks.

Duties connected with fisheries, meteorological reports and a variety of odds and ends are all part of the Coastguardsman’s life. Recruits for the Service are obtained from ex-naval officers and men, generally pensioners. They are “handymen” and in the event of war, when the Admiralty takes over, naval discipline and routine could readily be restored.

Recruits for the Service are generally taken from among men between the age of forty and forty-six, and the normal retiring age is sixty, but eyesight tests have to be passed at fifty and fifty-five to ensure that an efficient look-out can always be maintained.

A CONCRETE WATCH-HOUSE built by the Board of Trade for the Coastguard. The number of stations amounts to more than 250, of which fifty-three are in the North Scotland Division. The coasts of Great Britain and Northern Ireland are divided into twelve divisions for administrative purposes. In the most important coastguard stations watch is kept, day and night, by four men. They are in telephonic and sometimes wireless communication with the various authorities.

You can read more on “The Drama of Life-Saving”, “His Majesty’s Customs Service” and

“Smugglers and Revenue Cutters” on this website.