© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Smugglers and Revenue Cutters

Many and ingenious were the devices used by the smugglers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to deceive the Revenue men. There are few stories of adventure as exciting as some of the incidents in the hazardous life of these law-

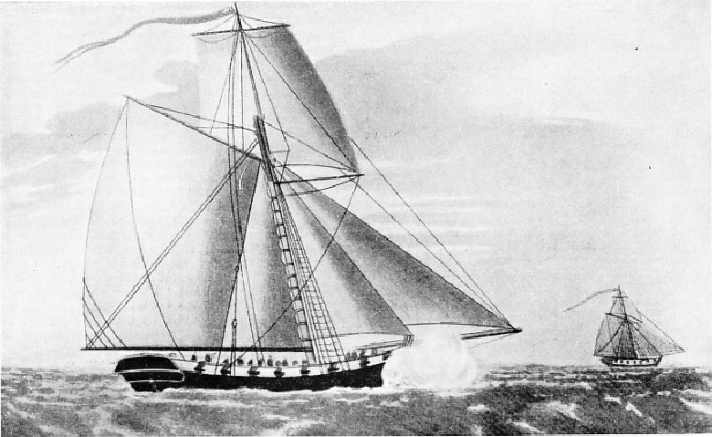

A REVENUE CUTTER in full chase of a smuggler. This illustration is reproduced from an aquatint in colours after T. Soutter, published in 1794 and now preserved in the famous Macpherson Collection at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich. The revenue cutter is called the Greyhound.

MOST of us at some period of our lives have revelled in those exciting stories about the old smugglers and their enemies, the preventive men; the secret signals on the cliff-

The grand adventurous epoch, with all its thrills and subterfuges, lasted from about 1700 to 1860. During that brief span of 160 years we have so many escapes and counter-

While naval battles were being fought in ocean-

Along the whole English coast-

From the earliest days -

Right down to the days of Charles II sailors still “risked their necks for 12d. a day”. The greatest amount of the wool was sent from Romney Marsh (Kent), whence it was smuggled after nightfall on board small craft. In the year 1676 was started a service which finally became that of the Revenue cutters. Among the smaller seventeenth-

These smacks had what was then a somewhat new type of rig, the sail being set on a long gaff resembling that of the Norfolk Broads wherry. They were selected from such places as Margate, Gravesend and Queenborough, and hired by the Commissioners of Customs, but they did not have much effect. Although William III sent two small warships and four armed sloops to cruise constantly between the North Foreland and the Isle of Wight, and although he forbade any one living within fifteen miles of the Kentish or Sussex shore to buy wool, yet the secret exportation still continued till the end of the eighteenth century. Long before this time it had become more profitable to smuggle by import. The Romney Marsh wool-

The wars with France during the reign of William and Mary rendered the smuggling into England of silk and lace (as well as much Jacobite correspondence) fairly easy, and thus the menace increased. Small gangs of ten expanded into hundreds of villagers, and those with cellarage arranged to store the illicit imports carried across by French armed luggers, whose crews openly defied the Revenue men.

Distance No Deterrent

The situation became so bad by 1713 that while His Majesty’s naval ships were active in the English Channel doing what they could, dragoons were sent to co-

Considerable trouble was also caused because the Isle of Man had become a great contraband depot whence dutiable goods poured into Liverpool. The problem of the Revenue men was twofold; first, the uncertain and shifting sands of the Mersey were too dangerous for a Customs’ sloop -

It was most certainly a thoroughly corrupt age, and moral standards had descended to a low level. Not even the Admiralty sloops could be trusted. Thus in 1729 the Southampton Customs officers reported that every time the Admiralty sloop Swift went across to Guernsey on her preventive duties, she used to arrive back with large quantities of wine, brandy and other dutiable goods, her excuse being that they were “ship’s stores”. She therefore had to be examined every time she reached Southampton.

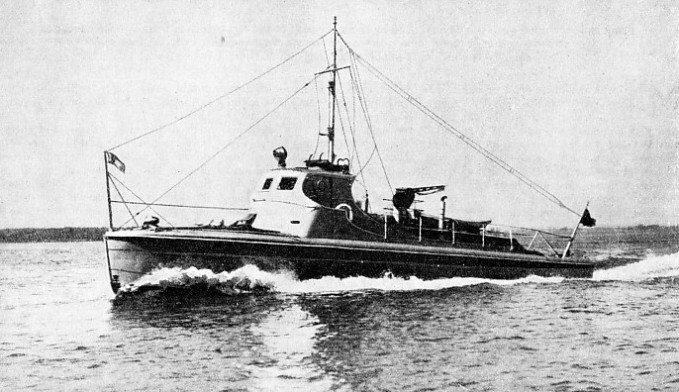

A MODERN STREAMLINED REVENUE CUTTER used in Canada against rum-

The Hampshire coast in the neighbourhood of Hurst Castle and Beaulieu was a popular dumping area for goods from the Channel Isles. Essex, Kent and Sussex were favoured localities for smuggling from such ports as Calais, Dunkirk and Flushing. Distance was no deterrent. One small Bridlington (Yorks) sloop used to sail over the North Sea to a Zeeland harbour, fill up with tea, tobacco and gin, and then land the cargo quietly anywhere between Bridlington and Spurn Lighthouse. So also Dutchmen would come over to Grimsby Roads or farther down the coast. One notorious foreigner, skipper of The Brotherly Love, used to run as many as 166 half-

The task of the Revenue authorities was still difficult, and life aboard their craft was not always enviable. The crews in normal times were cooped up for lack of space, and when it came to a real fight they might be maimed for life or killed. Moreover, some were disinclined to attack their own friends. It should be remembered that no small proportion of these Government crews were themselves ex-

On one occasion fifty smugglers by sheer determination ran a valuable cargo of tea and brandy at Benacre in Suffolk, and another band of sixty at the same place repeated the performance only a fortnight later. On such ventures fifty local horses were needed to carry the goods away. In one half year over 3,500 horse-

A good deal of this tea came from the East in Dutch vessels and reached Flushing. But the Dutch were not great tea drinkers, so Dutch and English smuggling vessels used to run this produce in their cutters of forty and fifty tons towards Folkestone. These vessels would approach to within three or four miles of the shore, and be met at night by smaller boats which at the right opportunity landed the stuff. This was easier than might be imagined. In view of the assistance of middlemen, the dissemination of false news, the warning lights from the cliff, the terrorizing of Customs officers and civil magistrates, and the local fishermen’s audacity, the trade could not be stopped.

THE ARMAMENT OF A REVENUE CUTTER sometimes included as many as twenty-

Twenty or thirty cargoes a week came in safely, and Flushing became so important that it bought Folkestone craft and tempted English shipbuilders to pursue their calling in Dutch territory. The smugglers themselves were rewarded by the tea-

jeers, as a posse of dragoons arrived. If these occasions were rare, it was partly because the shore arrangements of the sympathizers were so excellent. When once the tea had been hurried inland from the beach no more fears need be entertained. It was readily sold to middlemen, who bought 1,000 lb. at a time. There were also a number of men known as “duffers”, who used to walk into the villages and towns wearing coats heavy with tea concealed between two layers of stitched cloth; hence they were said to “quilt” so much. At one time no fewer than 20,000 people were employed in England smuggling, and a gang of 500 men could be collected in many spots within an hour.

A serious feature was that at least £1,000,000 sterling was yearly being taken out of the country to pay for these illicit imports. Quite £800,000 was for tea alone and, when the price of tea rose, the dealers were making a profit of £2 on every 100 lb. of tea. The carrying of brandy in casks had additional advantages, because the weight made excellent ballast; and money was so plentiful that fore-

Smuggler Turned Naval Officer

Another remarkable personality was Captain Joseph Cockburn, who in the mid-

This could be done only by careful organization. The cutters needed to take out with them plenty of men, considerable sums of ready cash and merchandise by way of exports. To deceive the English authorities, whether at London, Dover, Rye, Folkestone or any other port, the cutter would sail with only a few hands and pretend she was about to fish. Having arrived some miles from the shore, she would be met under cover of darkness by a number of smaller craft bringing plenty of tough men, the necessary money and the merchandise. Before daylight these small boats would have got back home, and the cutter would be well on her way to Holland or France. There she would sell her cargo, buy the tea and brandy, and, having set sail, would be met at a convenient distance off the southern English coast. Having chosen a dark night and waited for a favourable signal from the land, she would disembark her goods. The boats would run the casks and bales into a suitably quiet spot, while the cutter came back into her original harbour.

An old trick practised by the richly-

The Deal boatmen who used to go out from the beach in their little luggers were first-

We need not marvel that the Admiralty and Custom House sloops were apprehensive of their own fate when opposed by the smugglers in strength. The smugglers would stop at no extremity when angered, and one July they had the audacity to seize the Custom House craft at Dover and coolly employ it for tea-

The West of England followed the example of the south-

Formidable Craft

Some of the North Sea smuggling vessels were formidable craft. They were powerful cutters of 130 tons, armed with fourteen carriage guns, four three-

The West Country smugglers could boast of two notable cutters. One was the Swift, of Bridport, Dorset. She was of 100 tons, mounted sixteen guns and had a crew of fifty. Her cargo space was large and she more than paid her owners during the year 1783; for she used to come across and land near Torbay in each trip 2,000 casks of spirits, as well as five tons of tea, which needed a beach party of 200 men to run it inshore. So, too, the 250-

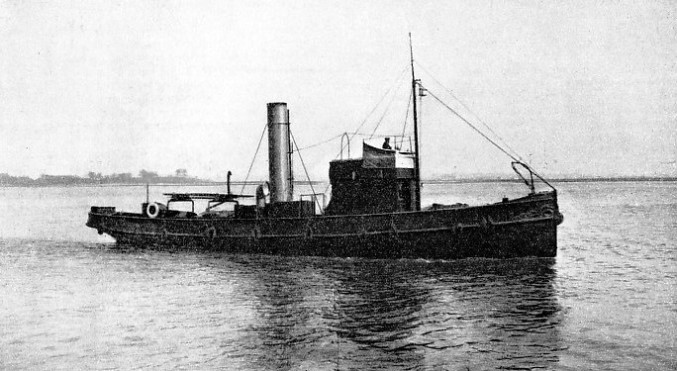

STATIONED AT GRAVESEND, on the River Thames, the St. George is one of the large fleet of H.M. Customs cutters. She does not chase smugglers, but her “rummage” crews detect large numbers of them and thus assist in the routine which, without causing any disturbance to shipping, saves the Treasury the loss of a great deal of revenue.

When we learn that such irregular sea strength was allowed, and that only forty-

Side by side in the same shipbuilding yard a smuggler and a Revenue cutter would often be under construction. Such good builders were the ablest firms that, a generation afterwards, they had become some of the leading British yacht designers. White of Cowes (I.W.), and Inman of Lymington (Hants), had launched numerous Revenue cutters long before Queen Victoria came to the throne.

The crews of these Revenue cutters wore red flannel shirts and blue trousers, with tarpaulin petticoats (so often shown in old paintings and prints). These petticoats were greatly appreciated when much boat work had to be done. So also the smugglers wore them for handling the brandy tubs. The cutters themselves, with enormous sail-

Many were the prosecutions made against landsmen signalling to smugglers in the offing. The commonest night signals were to wave a lantern from hill, house or prominent landmark; to take a flint and steel and set fire to a bundle of straw near the cliff’s edge; or to burn a blue light or fire a pistol. If signalling by day, the smuggling vessel could communicate with the shore by

lowering and raising a certain sail an agreed number of times. By about 1815 armed resistance and brutality among smugglers were largely being replaced by ingenuity and cunning. Still first-

Ingenious Hiding-

During the period 1816-

This practice was convenient in other ways, for if a smallish vessel were found with the kegs on board, her skipper would pretend that he had been out fishing, and that his nets had accidentally brought them up.

SEVERE WINTER CONDITIONS put a big strain on North American Revenue cutters as they have to operate in all weathers. This photograph shows the United States Revenue cutter Manhattan steaming through ice-

One smuggler had iron blocks for ballast cast hollow inside, and then sealed up again after having been filled with contraband. There was a phase when Kentish galleys rowed by six to twelve oars used to risk the weather, make for the Continent, and fill up with goods. Later legislation forbade the presence of small craft with more than four oars in the counties of Middlesex, Surrey, Kent or Essex. Even ballast stones Were found hollowed out and fitted with tins containing spirits, and potatoes from the Channel Islands proved to be rolls of tobacco covered over with a thin skin and clay.

It was customary for a smuggling vessel to be fitted with a rail just below the gunwale on the inside, running right round. When she was near her destination, and about to sink her brandy tubs for her accomplices to recover, these small casks were all fastened to a long rope and placed outside the bulwarks. To the rail this warp was fastened at intervals by stop-

Sometimes, to prevent anything suspicious from being found aboard, brandy-

The late autumn and winter, with their long nights, were always much favoured by the smugglers. One evening in November 1819, the Revenue cutter Badger, commanded by Captain Mercer, was cruising between Dungeness and Boulogne. At about 7 p.m. a lugger was sighted only a quarter of a mile off, steering towards the English coast.

The Badger gave chase and, as she drew near, the lugger kept altering course and agoing about on the other tack. Being a handy craft, she could do this more quickly than the big-

The Badger, however, was one of the fastest vessels in the Revenue service and, having once got the wind on her quarter, she reeled off her eight knots to the lugger’s five, until at last she ran right past and luffed up into the wind. Captain Mercer fired a warning gun, and ordered the lugger to heave-

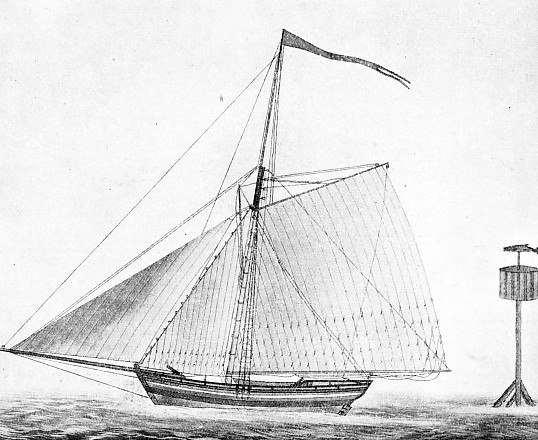

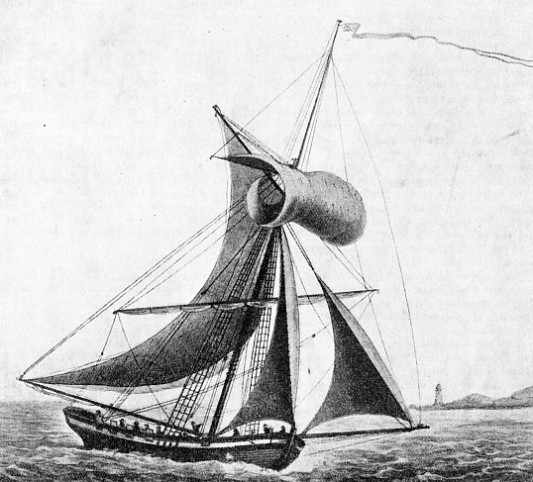

ONE OF THE FASTEST CUTTERS in the Revenue service, the Badger, gave chase one evening in November 1819 to a lugger, the Iris, of Boulogne With the wind on her quarter the Badger could make 8 knots. By a clever ruse the smugglers escaped in an open boat in the mist, but the Iris was boarded and an enormous amount of contraband was found in her. The smugglers were given up for lost, but only a month later one of them was captured by the Eagle.

This was really a lie to gain time, and the men got right away. The Revenue people rowed aboard the lugger and found 110 half-

Because of the darkness and the seas, neither the cutter nor the prize crew ever saw the smugglers’ open boat again. On such a night it would have been madness to try rowing across the strong Channel tides to Boulogne, some twenty-

A month later, on December 10, another Revenue cutter, the Eagle, was sailing off the Kentish coast at eight in the morning when she observed a lugger under all canvas heading for Boulogne. It was bitterly cold, and the falling snow made patrolling irksome. The Eagle’s captain had his suspicions and gave chase, running before a north-

The cutter’s boat, in charge of Mr. Gray, the Chief Mate, came alongside. Gray’s questions were answered in French. He was told there were seven men on board.

Gray summoned them aft, and found five French and two British. A man named Hugnet insisted that the British were merely passengers. Presently Hugnet contradicted himself and said there were not seven but nine in all. Gray therefore jumped down the fore peak to make a search. The place was dark, so he thrust in his cutlass and the cutlass reached something soft. It was the leg of a man.

When told to come out, this fellow obeyed instantly. He was followed by one more, and by others. In all, seven British men emerged. Most of them were dressed in short jackets and petticoat trousers -

A Fateful Coincidence

Gray soon found that altogether this lugger carried nine British and five French. No tubs were discovered, though other evidence such as a hoop and slings indicated that half-

It turned out that Albert Hugnet was the leading man not merely of this lugger, but of the Iris, which the Badger had chased a month earlier. He and the rest of the boatload that night had not rowed far, but had luckily been picked up by a French fishing craft only a quarter of a mile away. It was an escape from death, though this survivor now had to take his trial for both occurrences, and a sentence of imprisonment ended his cross-

As we search through musty old records, we find certain families through several generations engaged in smuggling and becoming notorious.

The smuggling industry flourished till about the year 1860. The high taxation had long since been removed from tea, and a gradual' preference for Scotch whisky rather than French brandy became a social characteristic. Thus the adventurous days, involving risky seafaring, passed away. With better wages, improved education, a higher moral code and more opportunities for honest recreation, there is no longer the same incitement to defraud His Majesty’s Revenue.

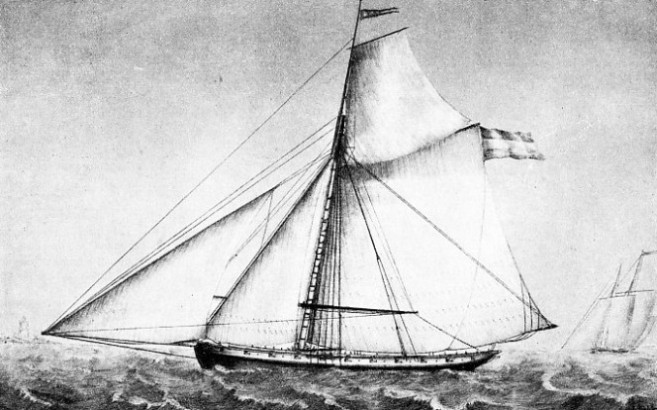

OFF THE KENTISH COAST early in the morning of December 10, 1819, the Revenue cutter Eagle, illustrated here, gave chase to a lugger that was heading for Boulogne under ail canvas. She overtook the lugger and discovered five French and two British sailors on board. A further search revealed seven more British. One of these men proved to have been among the smugglers who had escaped in an open boat from the Iris after her capture by the Badger a month before.

You can read more on “Fishery Protection”, “HM Coastguard Service” and

“His Majesty's Customs Service” on this website.