© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

How Yachts Are Raced

The regulations and rules, international, national and local, which govern yacht racing have undergone considerable changes in the last thirty years. Many conditions make yacht races difficult for the layman to follow

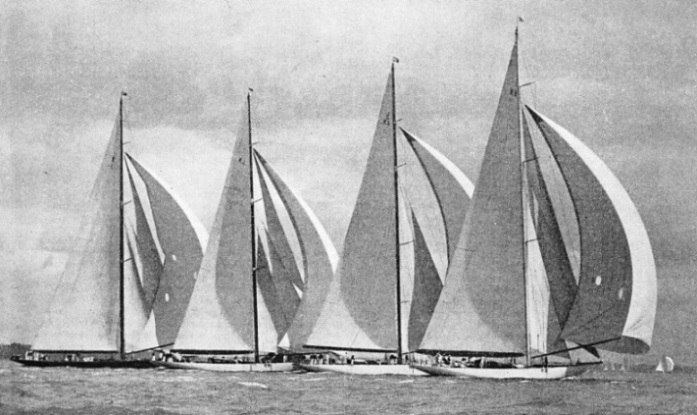

FOUR LARGE RACING YACHTS whose names are familiar to the general public. The Candida is followed by Shamrock V, the late Sir Thomas Lipton’s famous America’s Cup contestant, and by the Astra. The black-

IT is unfortunate that yacht racing, which is one of the finest sports in which a man can take part, is one of the least popular from the spectator’s point of view. This is partly because the competitors are out of sight of any one point for a large part of the race, but mainly because the average layman finds it impossible to understand the handicapping system. There is a large following for the cynic who said that the system was so confusing that only the yachts themselves knew who had won. Not all yachts, however, race, with a handicap, and the system, once worked out by experts, is comparatively simple.

Yacht racing is broadly divided into class racing — international, restricted or one-

For years in the middle of the nineteenth century efforts were made to race yachts under handicaps with every imaginable basis —length, tonnage and other measurements — but they were all open to objection, and while there was no central body to control the system there was bound to be confusion. This was especially so when yachts from one centre visited another. Matters

improved appreciably when the Yacht Racing Association was formed in 1875. One of its principal objects was to group yachts together in such a way that they could race without time allowance. Another was to evolve a system of time handicap which could be applied throughout the country and which would be fair to everybody. It began operations simply enough by introducing the Thames Measurement tonnage rule — by which yachts are still measured — and grouping the boats on that basis — five-

The next system was to multiply the length of the yacht by her sail area and to divide the product by 6,000, the result being her “rating”. This was successful for a time and encouraged the improvement of hull form from the straight stem to the clipper and then to the spoon bow; but it was apt to produce a small boat of light displacement, fast but wet, and it was feared that all yachts would tend to group into big classes.

In 1896, to produce a fuller body, the first linear rating rule was introduced, which, to find a boat’s rating, “taxed” various features, including girth. That rule proved easy to circumvent and had little or no effect, but in 1901 the improved linear rating rule was introduced on the suggestion of Alfred Benzon, a Danish mathematician. He wanted to check the tendency towards hollow sections, lack of head-

In 1906 a great advance was made by the holding of the first International Conference between the various yacht racing authorities. The rule then framed generally applied from January 1908. The greatest change was that the strength of the yachts’ hulls received full attention. Lloyd’s Register, the Bureau Veritas, Germanischer Lloyd and other classification societies were empowered to control the scantlings of the yachts built, so that it was no longer possible to build mere racing machines which were appallingly weak. The ratings arrived at were on a metric basis, but this had no relation to the length and was obtained by formula.

Regulations Circumvented

The 1908 Rule was the first which attempted to measure the effective sailing length of a yacht instead of her water-

As in all other rules, various features which made for speed were taxed, and if a designer paid undue attention to any one of them he had to sacrifice something else. In this rule sail area was lightly taxed so that a slight alteration in the hull would permit an enormous increase in the canvas carried. The early boats built to it were good; they gave fine sport, and had healthy seagoing hulls and good accommodation. From 1912 onwards the designers discovered how to drive the proverbial coach and four through the regulations. Without breaking the rule it was possible to build just the freak boats which the rule had been designed to prevent.

The life of the rule expired during the war of 1914-

OFF COWES, IN THE ISLE OF WIGHT, the largest British racing yachts compete during Cowes Week, the first week in August. This photograph shows a scene on the deck of the Westward, one of the largest racing yachts, of 323 tons, Thames measurement.

The International Yacht Racing Union Rule of 1920 is intricate in its measurements, but its results resemble those of the “length by sail area over 6,000” rule to which reference has already been made. Yachts built under the 1920 Rule can take every advantage of the development of naval architecture, The basic rule of measurement is coupled with restrictions, especially regarding minimum weight of hull with its accompanying strength, which prevent the building of freaks and which can be modified without changing the root principle of the rule. As an example of how it works, the modern 12-

The restrictions provided for are brought in whenever the design gets away from the original intention of those who framed the rule. For instance, the acknowledged sail area is roughly equal to the Bermudian mainsail plus 85 per cent of what is known as the fore triangle, the sail before the mast. But balloon headsails, parachute spinnakers and the like have been introduced within recent years, so that a 6-

The Americans did not join in these European rules, but had their own types of yacht, which were quite different. Enthusiasm for the British-

The International Rule

The yachts of the J class that race in European waters are too expensive to be numerous, but their contests are always the great attraction to the layman watching the regattas. The cost of such a boat depends entirely on the ideas of the owner; it is possible to include fittings and “gadgets” up to an exceptionally large sum. The Endeavour and the Rainbow, of the J class, competed for the America’s Cup in 1934, and the cost of the two yachts differed greatly. The approximate details of a J class boat, subject to considerable variation in every individual yacht, are a length of about 85 feet on the waterline, 127 to 130 feet overall length, a displacement of about 140 tons and a sail area of rather more than 7,500 square feet.

The International Rule provides for 23-

The 12-

REFLECTED IN THE STILL WATERS of the River Lea, these yachts are typical of the smaller classes that race in the rivers and round the coasts of Great Britain. The yachts on the left are waiting for the start of a race organized by the Broxbourne, Hertfordshire, Sailing Club.

The 8-

Perhaps the best known of the International classes is the 6-

The 6-

National and Local Classes

Smaller than the 6-

King Edward VIII, when Prince of Wales, took a keen interest in this class and obtained for it large numbers of enthusiasts by the presentation of the valuable Prince of Wales’s Challenge Cup. These dinghies are not allowed to exceed 14 feet in overall length. The principle of limiting their overall length, instead of the water-

In addition to the international classes there are numbers of national classes all over the world, built to suit their people. The Norwegians have several classes which are governed by sail area alone, and other countries have other ideas.

A RIVERSIDE SPECTACLE. Yachts of the Thames Sailing Club at Kingston-

In addition to the international and national classes there are local classes so numerous that it is possible to mention only a few of the better known and more important. More of these are found in British waters than anywhere else, partly because of the individual taste of British yachtsmen and partly because local conditions vary so much that the ideal type in one district is anything but ideal for another district perhaps only a few miles away.

These local classes are often restricted classes, in which a general limit is laid down and designers have a free hand just as they have in the international classes, as long as they do not break the rules. The others are the one-

The idea of one-

The biggest one-

The trouble with all class racing except one-

Thus every season sees a number of yachts, built to class rule and often among the cracks of their day, no longer standing any chance against their newer competitors and therefore being relegated to handicap racing alongside other relegations — racing yachts built to special or obsolete design — fast cruisers and miscellaneous vessels. Handicap racing can give excellent sport and a yacht may enjoy many years’ life in it, for adjustments are constantly made to keep her chances reasonable. As a rule the yacht whose class career is over is cut down aloft and made far more comfortable for cruising with additional cabin fittings and the like.

Often auxiliary engines are installed to help her in making a passage and to let her get in and out of harbour on race days with the minimum of difficulty. The screw naturally pulls down her speed when it is dragged through the water, but allowance is made for that in her handicap.

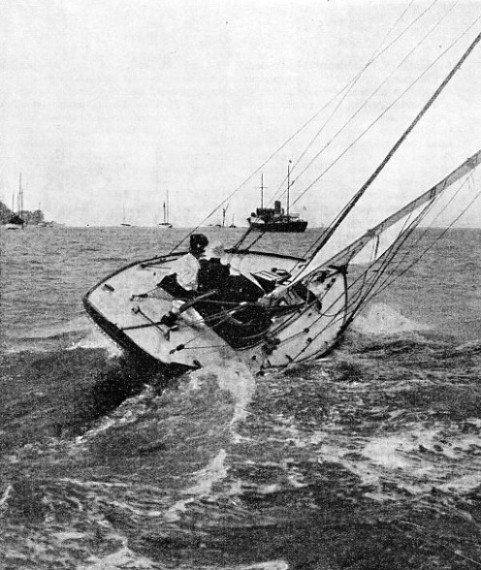

AN INCREASINGLY POPULAR SPORT, yachting and yacht racing takes place in almost every river, bay and estuary round the coast of Great Britain. This photograph shows the Harkaway, of the West Solent Restricted Class, typical of the smaller and less expensive craft that are so frequently to be seen in British waters.

The system of handicapping by time allowance appears at first sight to be puzzling to the layman and is often criticized on that account, but it is really simple and easy to understand. It is generally difficult, however, for the spectator who is not a member of the club, but who is watching the racing from the promenade or pier, to learn the time allowances which are adjusted for each day’s racing. Racing handicaps are fixed on a combination of two factors. One is stationary, the Yacht Racing Association’s speed figure, which is roughly what the yacht’s rating would be if she were built to rule. That allowance, as with all others, is worked out at so many seconds for a mile of the course, and remains with the yacht for the whole season. Every day however, the clubs’ “officers of the day” or, where they are lucky, a special experienced handicapper, fix an addition or reduction to this allowance based on the conditions ruling and the previous performance of the boat.

When these time allowances have been so adjusted that the corrected times of the yachts work out within a few seconds of one another, it means that the handicappers have judged their capabilities perfectly. Handicappers of such knowledge and judgment are rare and appreciated. To the yachtsmen who have each boat’s time allowance before them and can check their chances

to seconds, there is plenty of excitement in a handicap race; but the lay spectator sees only a number of boats sailing in at intervals, getting their gun and then returning to their moorings. Later, when the last straggler is home, some hoist their racing flags part-

As a handicap race of mixed types may often result in a heavily-

Before the race every owner is supposed to apply for his exact sailing directions. These describe all the marks on the course and the manner in which each is to be passed, some to starboard and some to port; but there is often carelessness on this point, and yachts are disqualified in consequence. Every yacht has her racing flag noted and a number is allotted to her lest she has to be recalled by the sailing committee. This recall number is not necessarily the same as the one stitched to her sail at the beginning of the season.

Three Main Sailing Rules

Racing routine varies to a certain extent, but the usual procedure is for each race to be distinguished by a flag flown at the most convenient point at one end of the starting line. Warning is given by a preliminary gun and by this flag run up on the flagstaff. The second gun and the Blue Peter (flag signal P in the International Code) give exactly five minutes to the start of the race, and during that period seconds have to be carefully watched. When the Blue Peter is hoisted the yachts are amenable to the sailing rules and any transgression may disqualify them.

There are three main sailing rules which are quite simple. The first is that the yacht on the weather side has the responsibility of keeping clear of the yacht to leeward. The second is that the yacht on the port tack gives way to one on the starboard, and the third is that the yacht running free must give way to the yacht close hauled. Some slight collisions are unavoidable, especially if there is no wind and the race has degenerated into a drifting match, but it is the duty of every yacht to avoid touching any of her competitors, and she is always liable to disqualification for doing so.

During the five minutes which precede the starting gun the yachts are all jockeying for the best position to cross the line when the gun is fired, and this is where a helmsman’s skill is shown to best advantage. There is generally a tide running across the line, and this tide and the wind have to be carefully studied so that the yacht, without fouling any of her competitors, may be as close as possible to the starting line ready to turn and shoot across it the moment the gun is fired. If any part of the boat is over the line, even if it is only a foot of her bowsprit, two guns are immediately fired in quick succession and recall numbers are exhibited. Every boat whose number is so shown has to go back and cross the line again.

Any owner who is dissatisfied with his competitor’s observance of the rules may lodge a protest with the Sailing Committee, shown by his finishing the race with his racing flag in the rigging, just over the rail. Nowadays protests are generally over some minor breach of the rules, probably accidental.

WHITE SAILS AND LIMPID WATERS. Small yachts are seen in this photograph taken during a regatta in Kiel Harbour, Germany, the scene of the yacht races during the Olympic Games of 1936. Regatta Week at Kiel is as important to Germany as Cowes Week to Great Britain.

You can read more on “The America’s Cup”, “Auxiliary Sailing Vessels” and “Yacht Cruising” on this website.