© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Yacht Cruising

The fascination of sailing a private yacht in British, or even in foreign waters is no longer the exclusive privilege of the rich man. This chapter shows how an amateur should set about yacht cruising in an economical and seamanlike manner, and this chapter is full of sound and practical advice

A SHELTERED ANCHORAGE in the Havre Gosselin, in the island of Sark, one of the smaller of the Channel Islands. In a yacht such as the Dyarchy (illustrated above) it is possible for the amateur yachtsman to reach such pleasant and out-

IN the old days yachting in all its forms was the exclusive pastime of the rich man. There were, it is true, a few odd amateur Sindbads, who, in small craft which they sailed themselves, went short coastal and Continental cruises ; but these individuals were looked upon as eccentric, if nothing worse. It is only within the last fifty years that the sport of practical yacht cruising by amateurs has grown to its present popularity.

This is chiefly because it has been generally discovered how much more interesting for an owner it is to sail his own small ship than to employ an expensive professional crew. So to-

Little ships can be bought quite cheaply and run economically by men of moderate means. Time was when the ownership of a yacht was the hallmark of the millionaire. What was once the aristocrat’s luxury can now be also the artisan’s hobby.

It is not generally realized, perhaps, that a small ship, well-

Another example, no less remarkable, was the single-

Few people have such long holidays that they can leave for months on end and voyage to the far places of the earth. But this is not necessary to savour the full joys of small boat cruising. It is astonishing how many attractive ports, quiet anchorages and fascinating rivers are to be found within a short journey of London. Thus, for the week-

There is a fascination about sailing one’s own little ship which can, perhaps, be found in no other sport. The nearest approach to it would perhaps be caravanning; but the caravan is sadly limited compared to the little ship whose roads are the open seas, the highways of the world. The yacht provides a home away from home, fully equipped with everything for living and sleeping aboard, all cunningly contrived so that every inch of available space is filled without making the boat seem overcrowded.

The freedom of the seas makes a contrast to the life of an office so great that it must be experienced to be realized. Out of reach of telephones, postmen, newspapers and all the other elements of rush and hustle in the modern civilized life, the yachtsman can pursue his own leisurely way, enjoying to the full the primitive pleasures of exploration. His is the Viking spirit — circumscribed it may be and limited by modern conditions, but the true spirit nevertheless.

The yachtsman is the modern Sindbad. In his week-

One year he may go down Channel to Dartmouth, to the charm of Cornish rivers, or to the fascinating Scilly Isles. Or he may go farther south, to France and the quaint Breton harbours, with their bright colours. He may go east to quiet Dutch waterways or, if he have three weeks or more to spare, he may even reach the Baltic Fjords. Every summer will see a fresh cruise accomplished, every winter the pleasures brought by memories of his last cruise, and the plans for the next.

In spring he will be busy fitting out his ship. In autumn she must be laid up and put to bed for the winter. In the dark, long evenings is the time to study navigation, to overhaul the boat’s

gear and to prepare for more ambitious cruises to come. Thus all the year the yachtsman is occupied and all his occupation brings him pleasure.

There are many ways of setting forth on a yachting cruise. Of these the best is also the cheapest. No sounder advice can be given to the would-

Initial Outlay £5 to £20

The man who has learnt first in large craft will never be able to sail small ones as well as the man who has been brought up in them. There .is this further advantage, that a small boat is cheap to buy and economical to run. So that if disaster should overtake the owner, and his boat be damaged or lost, the cost is not unduly heavy.

My advice would be to buy a small open or half-

much of the work the amateur is prepared to do for himself. The more he can do with his own hands, the greater will be the experience that he will gain thereby.

The successful skipper of any small craft is a man who knows how to do all the odd jobs which are required on board, and who therefore knows his own boat so well that he is sure of the strength of her hull and gear. In the course of doing his own fitting out, he will have discovered any weakness and this he will have put right. In any craft, large or small, when it comes on to blow, it is a great satisfaction for the owner to know that his gear is sound, because he has seen to it himself. No feeling is more uncomfortable in such circumstances than a doubt that the yard to which the work has been entrusted may have overlooked some possible source of failure.

AN EX-

This first year of sailing in inland waters should have taught the embryo yachtsman to know his boat and to be able to sail her, so far as the ordinary evolutions of everyday seamanship are concerned — such as sailing to windward, coming alongside a landing stage, running, gybing, setting and stowing sail and reefing. He will then be able in the next year to venture beyond the shelter of the river, and to embark on estuary sailing. There, in addition to the wind, he will learn to contend with tides and with rough water. He should buy a chart of the estuary on which he proposes to sail. During the winter he will derive much profit and enjoyment from studying the chart until he knows the position of every shoal and the characteristics of every light and buoy. He will now probably want to go rather farther afield than ordinary sailing will take him. In a suitable half-

His open boat can economically be turned into a cabin cruiser at night by the provision of an awning over the main boom, which is hoisted up the mast at the fore end and supported by a crutch at the after end. The sides of the tent are laced to small hooks or ring-

So much for the ideal beginning to a sailing career. But there are other ways in which it may be done. One method is to hire a small yacht on the Norfolk Broads and to indulge in a fortnight’s cruising. Thus experience can be gained in a short time for small expense. There is this advantage in Broadland sailing as a training: by reason of the narrow rivers and their winding courses, the yachtsman has to perform in quick succession all the many manoeuvres of seamanship.

Thus he may be running dead before the wind at one moment and tacking against it a few minutes later. He may easily do more tacking and gybing in a day’s sailing on the Broads than he does in a six weeks’ passage at sea. He also meets so many other craft in the confined space, that he quickly acquires, and of necessity, a sound knowledge of the Rule of the Road for sailing ships.

The sailing beginner may, on the other hand, have a friend who is already a keen and experienced yachtsman. In that event, if he can persuade his friend to take him as a member of his crew, he will learn much and quickly. A combination of experience as a hand in another man’s boat, with knowledge gained sailing his own really small craft by himself, is the finest possible way to learn to sail. There is no doubt that the amateur learns quickly from his mistakes, if he will but make up his mind never to make the same mistake twice.

Having learnt the elements of sailing in one or other of these ways, the amateur yachtsman will undoubtedly want to acquire a sea-

To such a suggestion there can be only one answer — don’t! A good sound hull may, it is true, be bought cheaply, but that is only the beginning. The cost of materials alone for a satisfactory conversion will amount to more than the completed craft is worth, and when the little ship has been decked, ballasted, rigged and provided with sails, the owner will find that he has to launch out in heavy expenditure before she is ready for sea Anchors, cables, lights, compass and the like have all to be bought, and the bare interior has to be equipped with mattresses, cushions, stoves and scores of other fittings before it is habitable.

By the time all this has been done the man who has been ill-

By the time all this has been done the man who has been ill-

even have the consolation of feeling that he has a good boat.

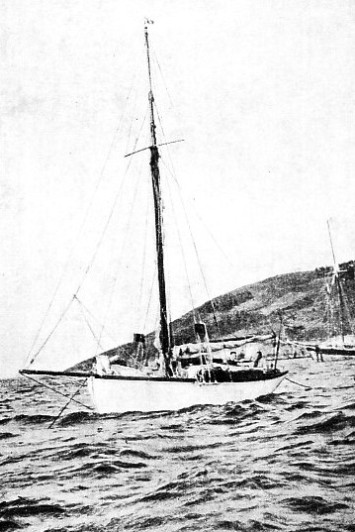

A REMARKABLE SINGLE-

She will be ugly, crank and a bad sailer because she was not originally designed to sail. She will break his heart going to windward, she will be so unhandy as to be unsafe and her second-

For his first sea-

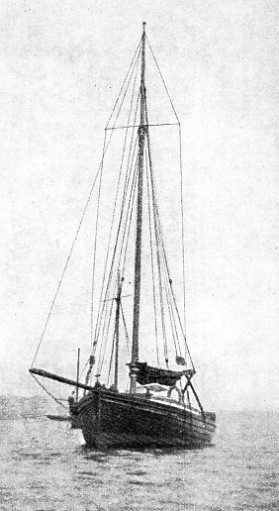

My own first craft would serve as a good example of the type of yacht in which the advancing amateur might begin his sea-

Her accommodation was arranged as follows: Aft was an open well or cockpit, used for steering. From this folding doors gave access to the saloon, where head room of about 4 ft. 9 in. was provided by a raised cabin top, and light by a small skylight in the forward end and a port-

Here were arranged the galley, the chain locker, racks for side lights and a good deal of storage space for spare gear. A folding canvas cot on the starboard side provided additional accommodation for one person.

A 9-

In the choice of rig, I would strongly advise the amateur to go for the cutter. The gear is less complicated than in a yawl or ketch, and the boat will be better sailing to windward. Although there is something to be said for the simplicity of the sloop, with its single headsail, it is more than counterbalanced by the fact that this one large headsail is more difficult to handle than are the two small ones of the cutter. It is always possible, moreover, for the cutter to be handled with the mainsail and one headsail only, while the other is shifted or reefed.

The amateur in his first sea-

A GOOD BREEZE off the Breton coast. This photograph shows the ex-

Another thing which the amateur yachtsman will soon discover is the use of the lead line. This is, when navigating in shallow water, one of the most valuable pieces of gear on board. In the underside of the lead itself is a small hollow that can be filled with grease to pick up some of the bottom of the sea. By this means it can be ascertained whether the bottom is mud, or fine sand or small shells.

As the nature of the bottom, as well as the depths of water, is marked on the chart, his lead line, at night or in foggy weather, taken in addition to his compass and his log, will give the owner a good idea of his position, and will warn him if he is getting into shallow water.

The log is a sort of sea cyclometer, which, on long passages, the yachtsman uses to tell him the distance he has sailed. It consists of a rotator with the blades set at an angle so that the log revolves when towed through the water at the end of a line. The other end of the line is attached to the wheel of an instrument, which, as it turns, records on a dial the miles run.

In the library of his small ship the yachtsman will carry his nautical almanac, in which the time of high water at the ports along the coasts will be recorded, and also the character of the various lights and buoys by which he is helped in the navigation of his ship. It will contain also information about the way that the tides run, for he will quickly learn that with a head wind and a contrary tide, he will make no progress, even if he does not lose ground.

A problem that will confront the owner with his first sea-

The best way for an owner to set about finding suitable permanent headquarters is to join a local yacht club, and to discover from his fellow members where the best moorings or the best berthing places are to be found. Moorings for a 7-

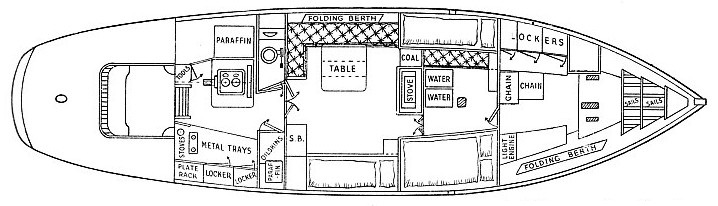

THE ACCOMMODATION PLAN OF THE CARIAD shows how a 26-

An organization called the Cruising Association provides for yachtsmen much the same service as the A.A. or the R.A.C. does for the motorist. The Cruising Association, however, does more. It provides a register of boatmen, with their charges, in nearly every yachting port in the British Isles. It also publishes the most complete book of sailing directions for yachtsmen that has ever been complied, and the club in London has one of the finest yachting libraries in the world.

After a year or two’s experience in a 7-

My own preference is for cruising. Every year I endeavour to make a long passage to some fresh cruising ground, such as the north coast of Spain or the west coast of Norway. I prefer to spend most of my holiday exploring the place to which I have sailed and then to make a long passage straight home.

My own preference is for cruising. Every year I endeavour to make a long passage to some fresh cruising ground, such as the north coast of Spain or the west coast of Norway. I prefer to spend most of my holiday exploring the place to which I have sailed and then to make a long passage straight home.

The craft in which my cruises for the last ten years have been carried out is the ex-

seaworthiness by any other craft in the world.

On long passages and with a fair wind I use a square sail which is similar in appearance to those carried by the old revenue cutters of long ago.

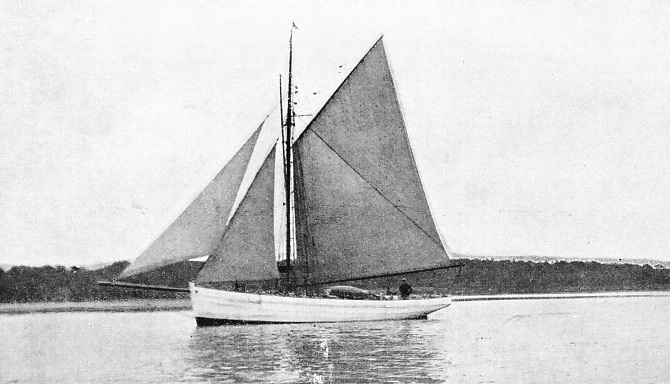

A SUITABLE CRAFT FOR THE NOVICE. The 6-

You can read more on “The America’s Cup”, “How Yachts are Raced” and “Thames Sailing Barges” on this website.