© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The “America’s” Cup

The first of the historic races for the America's Cup was held off the Isle of Wight in 1851. Since that date the rivalry of the British and American contestants for the valued cup has been the subject of great public enthusiasm on either side of the Atlantic

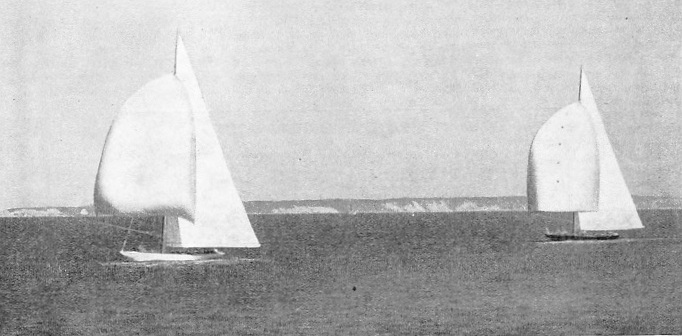

THE DECISIVE RACE in the America’s Cup race of 1934, off Newport, Rhode Island, U.S.A. The British challenger was T. O. M. Sopwith’s Endeavour, designed by Nicholson. The American defender, Rainbow, was designed by Starling Burgess. This photograph shows the Rainbow pulling away from the Endeavour as the two yachts approach the finishing line.

As a general rule the public does not take much interest in yacht racing. There are few opportunities, and when the layman does see a race he finds that the boats are often out of sight for the greater part of the time. Moreover, the handicapping system is so complicated that it is difficult to tell which yacht has won. The periodical contest for the America’s Cup, however, excites immense public enthusiasm, although it interests the regular yachtsman perhaps less than other races of minor public importance.

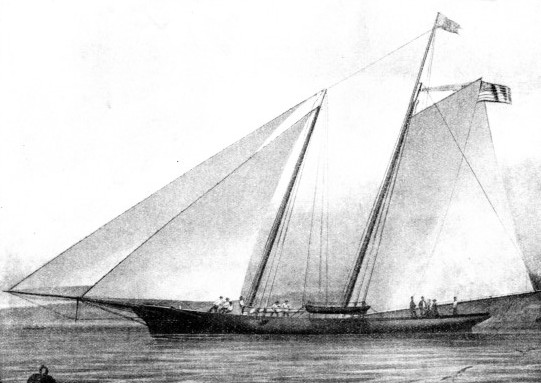

The contest for the cup originated as long ago as 1851. The famous clippers had given American shipbuilding a wonderful reputation for speed under sail. The Americans determined to show the world, and Great Britain in particular, that they could build fast yachts as well as they could build big clippers. The America, a schooner of 170 tons, was designed on the lines of the famous New York pilot cutters. Commodore John C. Stevens, of the New York Yacht Club, was the head of a syndicate of Americans that included also his brother and several others. They asked a young architect named George Steers to design and build a racing schooner. This schooner was the famous America.

The most scientific ideas of sailing-

The America made a good passage of twenty days from New York to Havre, where Commodore Stevens joined her. Stevens was a brilliant man in many ways, but there is no doubt that he was temperamental.

When she arrived in British waters the America’s owners had considerable difficulty in arranging the single race that had been planned with one or other of the British crack yachts. It is often said that the British were nervous of meeting the America after she had raced the cutter Laverock in the English Channel. It was some time before the Royal Yacht Squadron offered a cup, valued at one hundred guineas, for an open race round the Isle of Wight, without handicap, the trophy to become the property of the winner. Twenty British yachts were entered but only seventeen started. Their tonnage ranged from 47 to 392 and their designs included most of the, yachting types of the day.

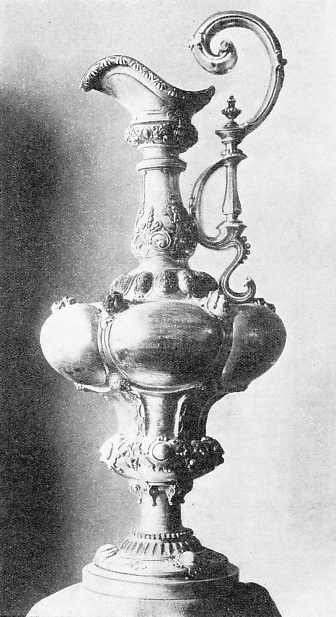

THE HISTORIC TROPHY for which British and American yachtsmen have contested since 1851. In that year the Royal Yacht Squadron offered this cup, valued at a hundred guineas, to the winner of a race between seventeen British yachts and the American schooner America. The America came home two miles ahead of her nearest rival and won the cup.

Against this miscellaneous collection the America sailed, handicapped by a lack of local knowledge and a poor start. In 1851 yacht races were started from anchor instead of the first across the line as at present. There is not the least doubt that the America was the fastest yacht in the race.

Her hull was more scientifically designed than those of most British boats and her cotton sails were superior to the hempen bags that were the best in the British fleet. She beat them all by a good two miles. The 47-

After the race she was sold to British owners and her adventures began. She raced a little, cruised a little and changed hands several times. When the American Civil War broke out and the Federals began a blockade of the southern coast-

The hundred-

The famous “deed of gift” was an ordinary letter, exceedingly vague in its terms. The size of yachts was not stipulated, it was not laid down whether the trophy should be contested in a single race or in a series, and everything was to be determined “by mutual consent”. The donors, obviously knowing nothing of what a complex sport yacht racing was to become, sowed the seeds of infinite trouble in expressing their desires so vaguely. At the same time they had inaugurated a series of matches unique in the history of sport at sea.

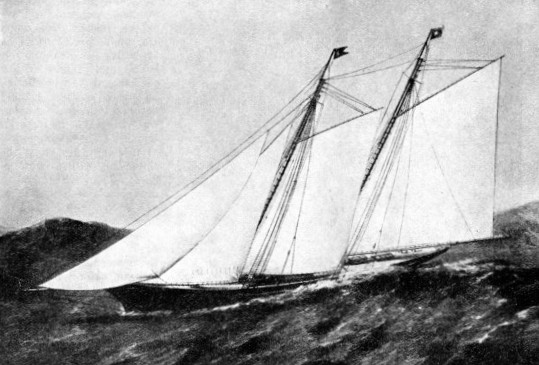

The first suggestion of an international race for the cup came in 1863 from Mr. James Ashbury, whose yacht Cambria was one of the finest British schooners, Numerous letters passed before Mr. Ashbury decided to sail across to America in the Cambria and make the necessary arrangements. This crossing developed into a race with the American schooner Dauntless, owned by Mr. James Gordon Bennett. The two yachts finished with only 1 hour 17 minutes between them, the Cambria winning.

It was finally arranged in 1870 that, no fewer than twenty-

Mr. Ashbury sold the Cambria, and she ran as a cargo vessel for many years afterwards. In the following year, 1871, he sent in another challenge. He was not satisfied, however, with the conditions in which the Cambria had raced. Finally the New York Yacht Club agreed that the cup should be awarded after a contest between single yachts, but it insisted on having a team of four ready and withholding the name of the defender until the morning of the race.

This gave the Americans a big advantage, for they could choose their boat according to the conditions prevailing, while the challengers had to accept these conditions whether they suited their boat or not. The New York Club selected two keel schooners for use in heavy winds and two lighter boats with small hulls and centreboards for light weather.

Mr. Ashbury built the Livonia, a magnificent sea-

Four races were sailed in October, 1871. In the first the Columbia beat the Livonia by 27 minutes 4 seconds; the second she won by 10 minutes 33 seconds. In the third race the Columbia had trouble aloft and the Livonia won by 15 minutes 10 seconds. In the fourth and fifth races the Sappho was chosen and beat the Livonia by 33 minutes 21 seconds and by 25 minutes 27 seconds respectively.

A certain amount of ill-

Nobody expected the Canadian to win and she was lucky in being defeated by only 10 minutes 59 seconds in the first race and by 27 minutes 14 seconds in the second. The attempt, hopeless as it seemed from the first, did yachting a real service, because it caused the defenders to alter their ideas to a great extent. By eleven votes to five it was decided that in future the race was to be made more sporting in that only one defender was to meet the challenger.

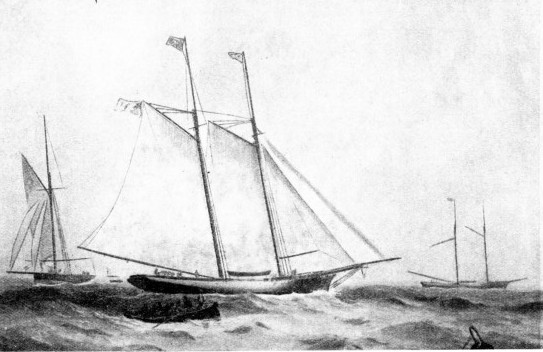

THE FIRST BRITISH CHALLENGER for the America’s Cup was the Cambria, 227 tons, owned by Mr. James Ashbury. Twenty-

The designer and helmsman of the Countess of Dufferin, Captain Cuthbert, was not discouraged. After five years he found financial backers and, with little money in hand, they built the sloop Atalanta. She had an overall length of 70 feet with a length of 64 feet on the water-

The new boat, built at short notice, was the Pocahontas. In the trial races she proved a failure and the Mischief, an iron sloop built in 1879, was chosen as defender instead. Her length overall was 67 ft. 5 in. and 61 feet on the water-

Then, in 1885, there came at last another challenge from Britain. The challenger was Sir Richard Sutton, a sportsman who soon made himself as popular in United States as he was in British waters and who did an immense amount to restore the prestige of the America's Cup. Sir Richard Sutton employed Beavor Webb, an Irish designer who specialized in the straightstemmed, plank-

The conditions of the race had been altered. The challenger was now to proceed under her own sail to the port where the contest was to take place. The Genesta was able to make the crossing, as was also the cutter Galatea, a boat that Beavor Webb built for Lieutenant W. Henn, R.N.

The proposal was made for a rather complicated series of races, first against the Genesta and then against the Galatea. The Americans had little experience of racing with the British plank-

It was fully realized that it was not going to be a walk-

In the first race the skipper of the Puritan, Aubrey Crocker, tried to bluff the Genesta, who had the right of way. The British skipper was not to be bluffed and the Puritan not only rammed her bowsprit but also was automatically disqualified.

The committee informed Sir Richard Sutton that he had the right to sail over the course and to win the race if he finished within the stipulated time limit of seven hours. He refused to take advantage of this, however, and his action caused tremendous enthusiasm in the United States. He left the country a popular loser. The Puritan had won the two races by 16 minutes 19 seconds and by 1 minute 38 seconds, after there had been several postponements and races in which the time limit had been exceeded.

Lieutenant Henn’s Galatea, sailed by himself, tried her luck in 1886. Again it was a contest between the British plank-

THE HEAVILY RAKED MASTS of the America, the famous schooner that crossed to England to challenge British yachtsmen and originated the contest for the cup named after her. The America was a schooner of 170 tons, designed by George Steers. Her overall length was 101 ft. 9 in., her extreme beam 23 feet and her maximum draught 11 feet. Her bowsprit was 32 feet long and only her mainmast carried a topmast. She had a sail area of 5,263 square feet.

To meet his challenge the syndicate that had owned the Puritan, with General Charles J. Paine at its head, again went to Edward Burgess for a sloop which was to be somewhat larger than the Puritan and of an improved design. The result was the Mayflower, a deeper boat than the Puritan, with outside lead ballast. Her overall length of 100 feet made her the largest sloop in the country and her sail area was 8,500 square feet. For reserves New York yachtsmen built the Atlantic, slightly smaller than the Mayflower, and rebuilt the old Priscilla.

Once she had found her form the Mayflower proved herself a flyer. She easily beat the challenger by 12 minutes 2 seconds in the first race and by 29 minutes 9 seconds in the second. Lieutenant Henn and his family made themselves so popular that there was nothing left of the old ill-

This challenge came from Scotland, where Mr. George L. Watson, who will always be remembered as the designer of King George V’s Britannia, designed the clipper-

This vessel was named the Volunteer. She was far less extreme than the Thistle. Watson’s boats were always lovely to look at, yet the Thistle, although she had the finest steel plating ever seen in a yacht, was too much cut away below water, so that she would not hang on to the wind. Although the Volunteer appeared to be a coaster beside the Thistle, her designer, Burgess, knew his business. Not only did the Thistle's form handicap her in general sailing but also, floating rather deeper than she was intended, she was penalized in time allowance.

Revolution in Yacht Design

The race proved rather disappointing, for the Thistle made big leeway and the Volunteer, in whose design many British ideas had been embodied, won the first race by over 19 minutes and the second by nearly 12. The Thistle returned to British waters and, in contrast to many America’s Cup yachts, had quite a long life before her. The German Emperor Wilhelm II was attracted by her appearance and bought her to be the first of his series of racing yachts named Meteor.

In 1893 Lord Dunraven issued the first of his challenges. He built Valkyrie II especially for the America’s Cup. The years 1887 to 1893 had, perhaps, seen the biggest change in yacht design ever known. This was the introduction of the spoon bow, deep keel, raking stern post and hollow fore profile, designed to go over the water rather than through it. Valkyrie II was an almost perfect yacht built to this fashion. Designed by Watson, she was similar to the Britannia, but planned to be better in the light winds that were to be expected over the America’s Cup course. She introduced into the competition the long overhangs at bow and stern, not measured but useful for speed as the yacht heeled. The Americans formed another syndicate, headed by Mr. C. Oliver Iselin, who approached the Herreshoff Brothers for his design. This firm introduced novel ideas in rigging which permitted a huge sail area. It also introduced metal strengthening to hold the eggshell hulls together.

The Vigilant, which was built of bronze below the water-

The Vigilant cost about £18,000 to build and over £20,000 more to tune up and race. The total amount paid by Lord Dunraven was about £25,000. After these races the Vigilant was sent across to British waters where she was easily beaten by the Britannia, although the Britannia could not beat Valkyrie II.

A RACE ACROSS THE ATLANTIC developed when the Dauntless, owned by Mr. James Gordon Bennett, met the Cambria on her way to America to challenge for the America’s Cup. The Dauntless, illustrated here, lost the unofficial race by a margin of only one hour and seventeen minutes.

Lord Dunraven challenged again with Valkyrie III in 1895. After a good many trials, Mr. Iselin’s syndicate again defended. It was, perhaps, the most unhappy series of races that ever caused ill-

The first race was won by the Defender with a margin of 8 minutes 49 seconds. The second race the Defender also won, but only by a narrow margin. The British yacht, however, had been disqualified for fouling her. She had been forced to do this by excursion steamers getting in the way, and Lord Dunraven would not sail again unless the committee undertook to keep the course clear.

This seemingly reasonable protest the committee dismissed, and in the third race Valkyrie III crossed the line and then retired.

Then came the famous series of challenges by Sir Thomas Lipton, who earned in America the affectionate nickname of “the world’s best loser”. Although at first he was not interested in the sport of yachting outside the spectacular America’s Cup race, he soon fell to the charm of it and became a famous sailing man.

His first challenge was with the Shamrock, the first America’s Cup challenger to be designed by Fife. This designer’s Minerva had visited the United States and had beaten all her rivals. The Shamrock was designed to have the minimum of resistance with a great saving of weight by the use of aluminium in hull and deck and steel aloft.

She was met by the Columbia, designed by Herreshoff and owned by a syndicate headed by Pierpont Morgan. The Columbia was probably the most beautiful yacht ever entered for the cup contest. Although she was of moderate design she beat the Shamrock in reducing resistance, and was sufficiently well built to become a cargo vessel when the submarine blockade had caused the disquieting shortage of tonnage during the war of 1914-

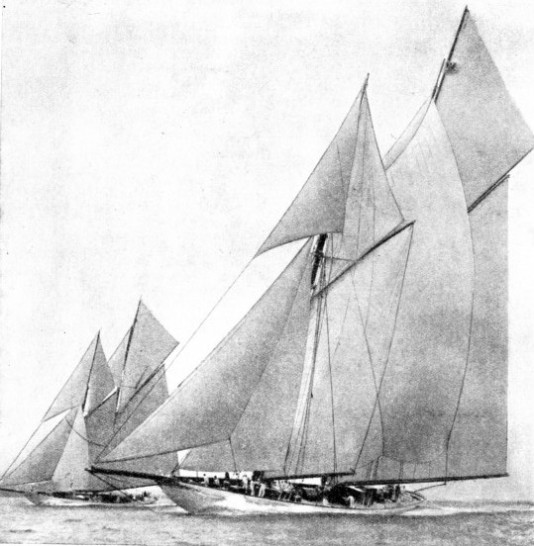

THE LONG-

For five days the yachts tried to race, but on every occasion the time limit expired. Then the Columbia won by 10 minutes 8 seconds. In the second race the Shamrock carried away her topmast and withdrew. There was another expiry of the time limit during a race and finally the Columbia won by 6 minutes 34 seconds. This series was reckoned to have cost either owner between £45,000 and £50,000.

In 1901 Lipton challenged again with Shamrock II, designed by Watson.

The Americans had a good deal of trouble over their defender. The Constitution was built by a syndicate to defend the race, but she experienced certain difficulties, especially with breaking gear aloft. The Columbia, under Charlie Barr, was brought out again to test her. The Columbia won so consistently that she was chosen instead of the new ship to defend the cup.

There was also considerable friction between Boston and New York. Mr. Lawson of Boston claimed the right as an American citizen to defend the cup, but the New York Yacht Club said that he must be a member of the club to conform with the “deed of gift”. He refused to join and built the Independence, a weird and wonderful yacht with a host of novel features but absolutely impossible to keep under control. She steered so wildly that her appearance was the signal for everything else afloat to run for shelter. She was broken up after a few weeks.

The first race was won by the Columbia with a margin of 1 minute 20 seconds, and the second by 3 minutes 35 seconds. She won the third race by only 41 seconds on a 43-

up in America immediately after the race, as she was useless for any other purpose.

For the races of 1903 Lipton ordered Shamrock III. She was a fast boat, built by Fife. Her trials convinced many observers that she would win the cup. An American syndicate, headed by Cornelius Vanderbilt, and including William Rockefeller and others, asked Herreshoff to build the Reliance. She was an absolute triumph. She embodied many points in the design of the Independence, but these were made practicable for the special purpose of the America’s Cup by Herreshoff’s genius.

The Reliance had a scow bow with long overhangs and a shallow body. With over 16,000 square feet of canvas she developed an astounding speed. She won the first race by 7 minutes 3 seconds, and the second by 1 minute 19 seconds. In the third race Shamrock III had an accident and did not finish. Thus the Reliance was triumphant. In 1914 Lipton challenged once again with another yacht, Shamrock IV. He had approached the Americans time after time to arrange terms, but the British designers had refused to build a scow similar to the Reliance. This was the only type of yacht that could possibly beat the crack American yachts that were intended only for America’s Cup races. They regarded such a vessel as dangerous, and were doubtful if she would stand the Atlantic crossing.

The Americans themselves had barred the scow type for all yacht racing except that for the America’s Cup. They finally accepted a challenge from a yacht with a water-

The challenger was designed by Nicholson, who did not like the American rule and who, therefore, tried to build the most powerful possible yacht on the specified water-

THE GERMAN EMPEROR’S YACHT, Meteor V, seen in the foreground, passing the Susanne at Kiel before the outbreak of war in 1914. The first Meteor was originally the Thistle. She unsuccessfully challenged the American yacht Volunteer for the America’s Cup in 1887. The Emperor Wilhelm II bought her and changed her name to Meteor.

The Americans built the Resolute to Herreshoff’s design, the Vanitie to Gardiner’s design and the Defiance for a Boston syndicate. These yachts raced in American regattas during 1914, and it was soon obvious that the Defiance was out of the running. She was nicknamed Deficit and retired, but the Resolute and the Vanitie were tuned up and improved in American meetings until 1917, when the United States went to war and racing was stopped. The crew of Shamrock IV heard the news of the outbreak of war in 1914 when she was at Bermuda. She was laid up at New York until 1920.

When the races were finally arranged in 1920 the Resolute was chosen as the American defender and was steered by Mr. C. F. Adams, later Secretary of the U.S. Navy. Sir W. P. Burton took the helm of Shamrock IV. The Resolute lost one race because of an accident, but eventually three races were won by the Americans and two by the British.

Lipton challenged again in 1930 and built Shamrock V for the purpose. The Americans went to Starling Burgess, the son of Edward Burgess, for the Enterprise, to Paine for the Yankee, to Clinton Crane for the Weetamoe, and to Herreshoff Junior for the Whirlwind. The Whirlwind was unsuccessful and after many trials the Enterprise was chosen. She had innumerable modern contrivances. Everything led below deck where there was a battery of winches with instruments recording the strain on every rope. Considerable weight was saved by building the mast of duralumin. The yacht was given the much-

T he Enterprise won all four races. Soon afterwards Sir Thomas Lipton Was in the grip of his last illness. Had he been spared he would certainly have built a Shamrock VI.

he Enterprise won all four races. Soon afterwards Sir Thomas Lipton Was in the grip of his last illness. Had he been spared he would certainly have built a Shamrock VI.

Another series of races was sailed in 1934, when a new challenger came forward in the person of Mr. T. O. M. Sopwith, who had proved himself a good helmsman and had won a large number of races in British regattas. He built the Endeavour to the American “J” class design, with certain slight modifications. After discussion the Americans made concessions concerning the use of machinery and “gadgets”, the weight of masts and other matters.

The Rainbow was designed by Starling Burgess and was tried against the old Vanitie and the Weetamoe. The Endeavour was designed and built by Nicholson. The yachts were masterpieces in their way, and the defenders made a number of concessions which showed clearly that they were anxious for a fair race.

The Endeavour was greatly admired by American yachtsmen when she arrived, and it was felt that she would give them a harder task than any boat that the British had yet sent across. There had been, however, certain ambiguities in the discussion of the regulations, and for this reason the Endeavour was at a disadvantage. Sopwith, fine helmsman though he was, had not the years of experience that were demanded of the helmsman of a crack racer. It was agreed that the cup should go to the winner of the first four out of seven races, and excitement ran high. The U.S. Navy kept the course clear and everything was ready for the best contest of the series.

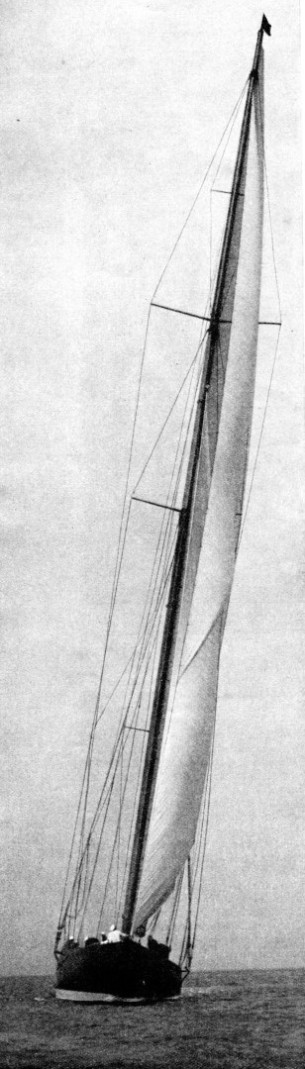

THE TALL MAST of Sir Thomas Lipton’s Shamrock V, with headsail set. This photograph was taken in May 1930, during a race from Harwich to Southend, Essex. In the same year Shamrock V crossed the Atlantic to challenge for the America's Cup.

The first race was in favour of the Rainbow, but the time limit expired before a result could be declared. Sopwith had suffered from a strike of his professional crew just before his ship sailed. He had replaced them with enthusiastic amateurs, but it was soon obvious that they were not equal to the perfectly drilled professional crew of the Rainbow. They did well, however, and the Endeavour won the second race after a tremendously fast contest, although she was handicapped by torn sails. The third race was called off for lack of wind and then, in a light breeze, the Rainbow had her revenge.

The Endeavour won the fourth race. In the fifth race the Rainbow had it all her own way and finished four minutes ahead. The defender won for the fourth time by a margin of 55 seconds.

There is no doubt that the America’s Cup contest has made an immense difference to the technical design of yachts and has spurred the architects on to make great improvements. It is a sport of millionaires, however, and the colossal cost of the contest must deter all but the wealthiest. Unofficially it is reported that the Endeavour cost £30,000 and the Rainbow £80,000, apart from the cost of maintenance and racing.

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this article.

You can read more on “How Yachts Are Raced”, “Racing at Two Miles a Minute”, and “Romance of the Racing Clippers” on this website.