© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Racing at Two Miles a Minute

Man’s ability to travel at two miles a minute on water is a wonderful achievement which is a direct result of years of experiment and keen rivalry in international motor-

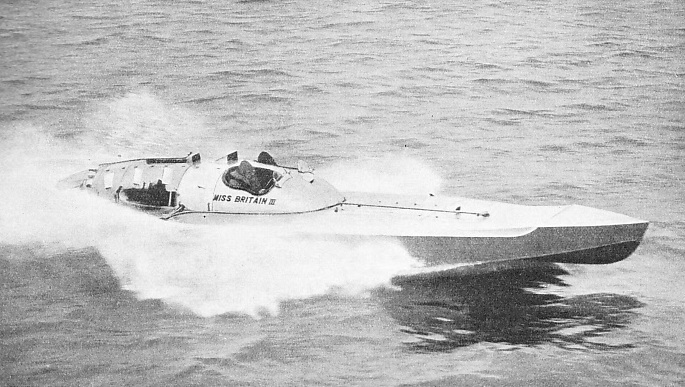

TOP SPEED. At the beginning of 1936 the world’s fastest single-

THE racing motor boat is the fastest of all craft. In fewer than fifty years the motor boat has developed from a slow launch into a craft capable of more than two statute miles a minute. It has cost millions of pounds and years of experiment to achieve this result. Only one boat, Miss America X, driven by Commodore Gar Wood, has been driven at this speed. Miss England III has, however, also reached a speed only a fraction below that of Miss America X. The cleverest engineers and the finest craftsmen among boat builders have co-

Although the world’s speed record was set up on fresh water, the first man to achieve 100 miles an hour on salt water was Mr. Hubert Scott-

The first motor boat on record was put into the water of a lake in Germany in 1886 by Gottlieb Daimler, the motorcar pioneer. She was a small launch little different in shape from the launches of to-

So uncertain were the performances of the early motors that the drivers had necessarily to be skilled mechanics able to diagnose and cope with any engine trouble. Many of the drivers were setting up in business as makers of internal combustion engines and had gained great experience from racing motor cars. Sometimes wealthy men bought motor boats, which were tuned up and raced by mechanics. Although many pioneers were motorists they depended upon boat-

Then, in 1903, Sir Alfred Harmsworth, afterwards Lord Northcliffe, offered a cup for international competition, to be open to boats of less than 40 feet in length, the boat and engine to have been built entirely in the country represented, and her driver to be of that nationality. The Harmsworth Trophy, the name of which was afterwards altered to the British International Trophy, although it is often referred to under the old title, is the blue riband of motor-

The first contest for the trophy was not international, because the interval between the announcement and the race was too short to allow foreign competitors to build special boats and engines. The race was held in the harbour of Queenstown (Cobh) and was won by Mr. S. F. Edge’s Napier I, which was driven by Mr. Campbell Muir. The boat at times attained a speed of nearly twenty knots.

This race introduced the second phase in the history of the motor boat, which was fast emerging from obscurity and experiment. The following summer of 1904 was marked by three big events -

The First Hydroplane

So many of the owners and drivers of motor boats were motorists that they looked upon the club now known as the Royal Automobile Club as their authority. The marine section of the club arranged the reliability trials on Southampton Water.

Nine boats competed for the Harmsworth Trophy off Ryde in the Isle of Wight, five being British, three French and one American. Mr. Edge drove the Napier Minor to victory at a speed of 23½ miles an hour, defeating one of the French boats, Trefle-

In the cross-

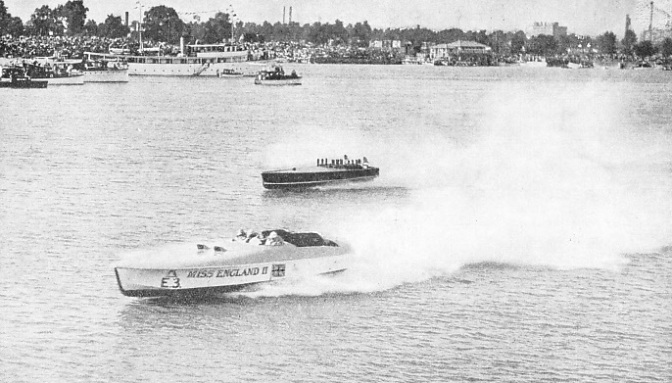

THE RACE BEGINS. This photograph was taken a few seconds after the starting gun had sounded for the Harmsworth Trophy race in September 1931. Mr. Kaye Don can be seen leading in Miss England II. The first race for the Harmsworth Trophy was in 1904. The length of each of the three heats must be between thirty and forty miles.

With the development of the internal combustion engine the speeds of fast boats increased. The ratio of the power to the weight of the engine became sufficiently favourable to cause boat designers to turn their attention to the hydroplane -

The American boat Dixie took the Harmsworth Trophy across the Atlantic in 1907, and it was not regained by Britain until the Maple Leaf IV was victorious in 1912. The Maple Leaf IV, a 40-

The difference in speed between the races of 1913 and 1920 was not great. But after 1920 the power and speed increased remarkably, making the cost of the craft so great that only the wealthiest could afford to consider an attempt to win. Indeed, Miss M. B. Carstairs, who entered several boats named Estelle, is stated to have spent about £100,000 on them in spirited but vain efforts to win back the trophy for Great Britain. The cost of financing one of the Miss England boats owned by Lord Wakefield has been put at £25,000. Another is said to have cost about £40,000.

The main problem is the ratio between power and weight. Commodore Gar Wood has preferred to pack as much power as possible into a boat that remains within the 40 feet limit of the Harmsworth Trophy rules. The British racing men have preferred to cut down weight by limiting the size of the engine and therefore that of the boat.

The Segrave Disaster

Some splendid craft have been produced by British engineers on the lines of this policy, notably by Mr. Hubert Scott-

The next British boat, Miss England II, was fitted with two Rolls-

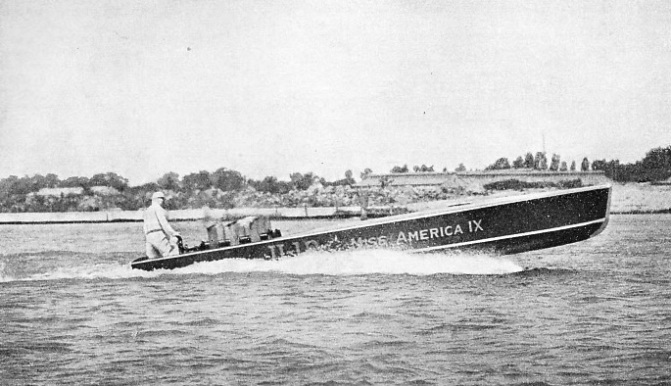

ON THE DETROIT RIVER. Miss America IX being given her first test run in August, 1930, when the boat, driven by Commodore Gar Wood, reached approximately ninety miles an hour. Gar Wood drove Miss America IX in the race for the Harmsworth Trophy in September, 1931, which was declared void. Later, in February, 1932, Gar Wood attained 111·71 m.p.h. in Miss America IX at Miami, Florida.

Mr. Kaye Don took the reconditioned Miss England II to Buenos Aires, and in April, 1931, set up a new record of 103·49 m.p.h. Later he went to Lake Garda, Italy. There he brought the speed up to 110·28 m.p.h. Meanwhile, Commodore Gar Wood had been trying to regain the record, but did not succeed. The rivals met in the race for the Harmsworth Trophy in September, 1931, there being a third contestant in Commodore Gar Wood’s brother, Mr. George Wood. The Commodore was in Miss America IX and Mr. George Wood in Miss America VIII. Mr. Kaye Don won the first race at a speed of 89·13 m.p.h., and was favourite for the second race.

This second heat was a fiasco which caused considerable comment at the time. Commodore Gar Wood was off before the starting gun, and Mr. Kaye Don followed; thus both were over the line some seconds too soon. The British boat capsized, and Mr. Don and his two mechanics were rescued. Mr. George Wood started at the right time, and claimed the race, but in the end it was declared void.

Miss England II was a wonderful craft, and Mr. Don handled her with great skill. She had only one propeller, which turned at 12,000 r.p.m., and weighed 15 lb.

Commodore Gar Wood persevered with his attempts on the record and reached 111·71 m.p.h. at Miami, Florida, in February, 1932, with Miss America IX. Meanwhile, Miss England III was built by Thornycroft’s and equipped with two Rolls-

About 100,000 spectators gathered to watch the duel between the two rivals on Lake St. Clair, near Detroit, Michigan. In the first race Miss England III was unfortunate. The throttle control and a pipe of the cooling system broke, so that one of her engines went out of action in the last lap, and the speed of the boat fell to little more than half. The boats began neck and neck in the second race, but a burst of flame came from the British boat, and the starboard engine gave out. Badly burned and bruised as he was, Mr. Don continued while his mechanic tried to rectify the trouble; but the great strain on the port engine was too much and it stopped. Thus Commodore Gar Wood retained the trophy. After this race Lord Wakefield decided to withdraw from sponsoring racing craft and record attempts. Commodore Gar Wood regained the speed record in September, 1932, at 124·86 miles an hour. He was the first man to achieve two miles a minute on the water.

Miss America X is -

In 1933 Miss Britain III was matched against Miss America X for the Harmsworth Trophy at Detroit, and put up a speed only slightly below that of Commodore Gar Wood’s boat, the horsepower of which had been increased to 7,800. This was a marvellous performance, considering the differences in size and power.

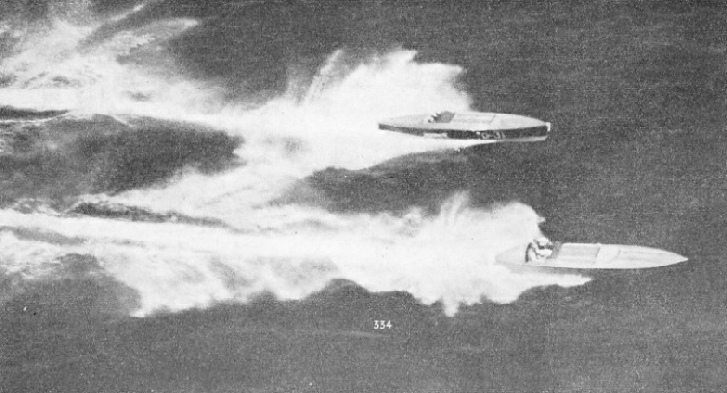

SPEEDING TO VICTORY. A remarkable photograph of two super-

You can read more on “Coastal Motor-

“Romance of the Racing Clippers” on this website.