During the war of 1914-18, coastal motor-boats played a part out of all proportion to their size. They attacked enemy submarines, destroyers, aeroplanes and patrol boats, laid mines and made smoke screens. On St. George’s Day, 1918, they rendered conspicuous service during the historic raid on Zeebrugge

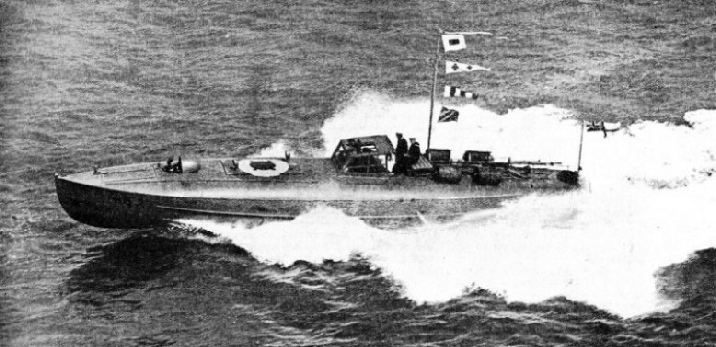

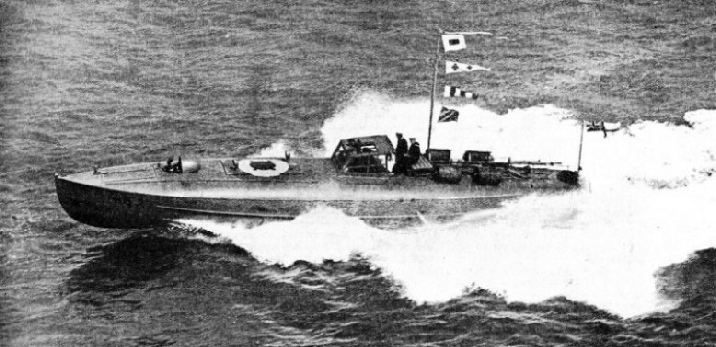

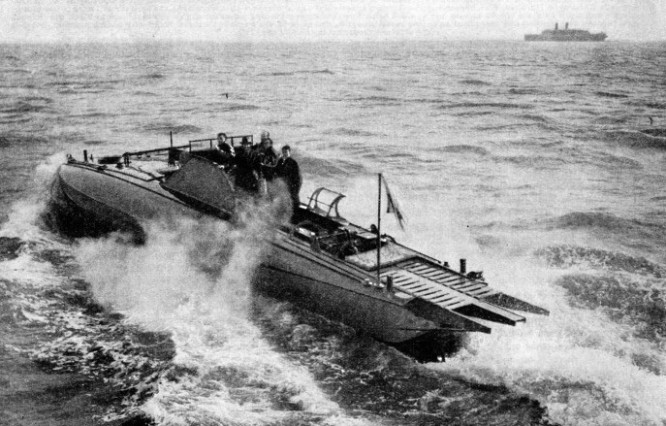

A 55-FT. COASTAL MOTOR-BOAT, built by John I. Thornycroft & Co., Ltd., of the type which proved of great service during the war of 1914-13. Numbers of these boats, based at Dover, Portland and Portsmouth, were used for anti-submarine work. There was also an advance base at Dunkirk, on the French coast. The boats generally carried two officers, two mechanics and a wireless operator.

THE smallest naval vessels that have passed through the ordeal of battle are coastal motor-boats, known as C.M.B.s. These are the small high-speed torpedo boats evolved in Great Britain by John I. Thornycroft and Company, Ltd. The C.M.B.s carry two torpedoes, and rely only on speed and helmsmanship to escape punishment. During the war of 1914-18 and during the operations in Russian waters in 1919 they proved their value. They are, in smooth water, the fastest naval craft, and in fair weather no other surface craft can catch them.

They must not be confused with the motor launches, or M.L.s, the larger and slower craft used for anti-submarine service and dropping depth charges. The coastal motor-boats may also be similarly employed when equipped with depth charges as well as torpedoes.

Considerable attention has been given by various naval Powers to these motor torpedo boats. One report credits the speed of new boats owned by a Mediterranean country as eighty knots, but this is considered an exaggeration. A speed on trial of fifty-five knots has been claimed for a French 60-ft. craft, and more than fifty knots for others.

The motor torpedo boat is a development of the steam torpedo boat that was superseded by the torpedo boat destroyer. The coastal motor-boats that helped to make history during the war were too small to be dignified with the title of H.M.S., and they were given numbers instead of names. Operated at speeds higher than that of a destroyer, and so small that they did not present much of a target, they were the scorpions of the sea and could tackle surface craft, under-water craft and aircraft. Although a well-placed bullet could incapacitate a C.M.B., the C.M.B.s sank Russian warships in action and played a worthy part in the raids on Zeebrugge and Ostend. Their success was due to the fact that they were skilfully handled by young and daring men who thought and acted quickly. Their speed, small size and vulnerability developed the individuality of the young officers in command. The speed of these boats, however, was of no advantage against an aeroplane, and when attacked from the air they had to dodge as cleverly as they could and fight the attacker with a machine-gun.

The C.M.B. is a boat similar to the fast racing motor-boats described in the chapter ”Racing at Two Miles a Minute”. It has more strength, however, than a racing hull. The type was evolved by Sir John I. Thornycroft and Mr. Tom Thornycroft after years of experiment with racing motor-boats. These boats were of the single-step design, and it was proved that, by fitting an angle or chine piece on the bow, so that the bow wave could not rise up but was thrown down laterally, the hull was greatly improved. Miranda IV, a, successful racing boat built in 1910, had this angle in the bow, with concave sections below it which became flatter and recurved as they got to the step. The after-body was slightly pinched in and hollow on the keel line, so that the water, having left the step, ran clear of the boat until shortly before it reached the transom. Although various governments had experimented with motor torpedo boats before the war, it was not until this improved design of hull was invented that these boats became effective. The steam torpedo boat was outclassed by the destroyer, which was larger and much more seaworthy; but during the war the destroyer, except in the Battle of Jutland and a few other actions, relied on her guns rather than on her torpedoes, and functioned as a cruiser and patrol boat. The C.M.B., however, replaced the torpedo boat and fulfilled other duties, notably patrol work in shallow, mine-strewn waters under the shore batteries of the enemy on the Belgian coast.

There were many intricate technical problems to be overcome before the C.M.B. came into being. One of the most serious troubles was the difficulty of carrying and discharging the torpedo. Early in the summer of 1915. Thornycroft’s submitted to the British Admiralty designs for a type of motor torpedo boat to carry a torpedo in a dropping gear. Shortly afterwards three young officers, Lieutenants Hampden, Bremner and Arison, of the Harwich Force, told Thornycroft’s that they had been advocating high-speed motor torpedo boats and that they had been authorized by their commodore to approach the firm.

They wanted a boat whose weight, including the torpedo, would not exceed that of the 30-ft. motor-boats carried in davits by light cruisers, with a speed of at least thirty knots and fuel capacity for a considerable radius of action. As the torpedo itself weighed about three-quarters of a ton, the weight problem was formidable. In addition no boat previously designed had been intended to be slung in davits with such a heavy load, and therefore the boats would not be strong enough for the strain. The greatest problem, however, was to find the best way of carrying and discharging the 18-in. torpedo specified. The dropping gear fitted in

picket boats was designed for a 14-in. torpedo and the boat had to slow down to discharge it; but the coastal motorboat had to attack and discharge the torpedo at high speed. The easiest solution was to carry the torpedo and discharge it over the stern, but this meant that the boat would have to turn, and so lessen her chance of hitting the target; at the same time it would add to the risk of the boat being hit. Finally, at the firm’s suggestion, it was decided to discharge the torpedo over the stern tail first. If the boat was going at the same speed as the torpedo there would be a chance of steering her clear of the torpedo.

The theory was tested by torpedo specialists from the Vernon with an experimental boat that was not exceptionally fast. The experts held that the theory was practicable provided the boat had a speed of over thirty knots.

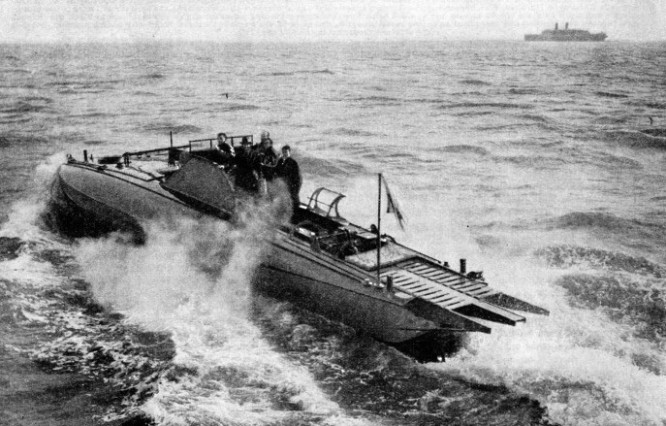

40-FT. COASTAL MOTOR-BOATS IN RUSSIA. After the Armistice in 1913 the advance base for coastal motor-boats at Dunkirk was closed. The boats were returned to the Dover base, and many officers were transferred to large ships. Officers with temporary commissions and ratings temporarily enlisted were demobilized. A number of boats remained in service, however, and later were used in naval operations against the Bolshevist forces, notably at Kronstadt, in Petrograd (Leningrad) Bay, and on the Archangel front.

In January 1916 the Admiralty approved the design and ordered twelve C.M.B.s, insisting on the greatest secrecy, so that the enemy would be taken by surprise. The engines were specially designed and the torpedo gear and fittings built at Thornycroft’s works at Basingstoke (Hants). The boats were built on an island in the Thames without exciting unwelcome curiosity in interested quarters. Three boats were ready in April 1916, and the South-Eastern (now Southern) Railway Company’s pier at Queenborough, near Sheerness, at the mouth of the River Medway, was the secret base. For some time the officers who had volunteered for service in the C.M.B.s lived on the pier, and the boats were so secret that most of the runs necessary for training the officers were made after dark.

The first boats were 40 feet long and carried one 18-in. torpedo. It was originally intended that the crew should consist of two officers. The officers had to know every detail of the engines as well as of the hulls, and they spent some time at Basingstoke watching the engines being built. As men in the artificer branch of the Navy were not accustomed to motors of the aeroplane type developing more than 250 horse-power, artificers and engineers joined the new branch to be trained.

It was a strenuous training, learning to handle boats in the dark at over thirty knots, to discharge torpedoes and swerve out of their way, to perform complicated manoeuvres and avoid sister boats. The twenty-four officers, however, who volunteered for the original twelve boats were enthusiasts. Lieut. Hampden was the original officer in charge. By the end of 1916 four boats were sent to Dunkirk, on the French coast.

Those who served on the Western Front in the winter of 1916-17 will never forget the cold that froze the whole of the front. Great difficulty was experienced in preventing the motors and torpedoes of the C.M.B.s from freezing. The boats, gear and personnel were all berthed in a steel barge, and a former bathing-hut served as the navigation office for Lieut. Erskine Childers, R.N.V.R.

Lieut. Childers was the yachtsman whose book, The Riddle of the Sands, written in the guise of a novel, had attracted much public attention. It unveiled the secret of German attempts before the war to embark and disembark landing parties of troops and to tow boats full of soldiers. Lieut. Childers was a splendid yachtsman and his name is honoured by yachtsmen of all nations. His exceptional knowledge of the German coast led to his appointment as navigator to the tiny force.

During the first few months only one officer, Lieut. Anson, was hit by a machine-gun bullet, and the boats all got home safely, although sometimes in a crippled condition.

Channel Patrols

Important experiments were then being made with a larger type for attacking submarines. This second type of boat was 55 feet long and had a speed of forty knots, compared with the thirty-three knots of the 40-ft. Class.

The larger boat carried two torpedoes, or one torpedo and four depth charges. Later, a still larger type of 70-ft. boat was produced to carry mines or torpedoes; but although the horse-power was 1,600, this type was not so swift.

After the successful trials of the first 55-ft. boat, the Admiralty decided to build a large number, and the cooperation of various firms of boat-builders and engine makers was secured. Each boat carried two officers, two motor mechanics and a wireless operator. There were not enough R.N. officers to be spared, and R.N.R. and R.N.V.R. officers joined the section. Many of the mechanics were Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders.

The 55-ft. boats were based at Portland, Portsmouth and Dover for anti-submarine duty. Dunkirk, the advanced base of Dover, was a lively station as the boats there had the opportunity of fighting German destroyers and patrol boats, as well as submarines. The C.M.B.s from Dunkirk patrolled tens of thousands of miles between the minefields in front of the entrances to Zeebrugge and Ostend, and often had to run the gauntlet of the shore batteries. A few boats were lost in this way. They went out in weather that kept the enemy motor patrol boats in harbour. For North Sea patrols a base was established near Harwich (Essex), and light cruisers of the Harwich Force carried a pair of 40-ft. C.M.Bs in davits.

AFTER ZEEBRUGGE. Coastal motor-boats returning to Portsmouth Harbour after having taken part in the naval raid on Zeebrugge on April 23, 1918. Under the command of Vice-Admiral (now Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger) Keyes, the operation caused the blocking of the channel leading into Zeebrugge Harbour, thus hampering the German submarines and destroyers that were using the harbour as a base. The motorboats were employed to make smoke screens and to mark with flares the correct turning points for the vessels that were to block the channel. Early in the raid two motor-boats torpedoed an enemy vessel alongside the mole of the harbour; others, fitted with trench mortars, bombed the seaplane sheds that lay behind the Mole.

Among the early operations of the Dunkirk boats was an action fought off the Belgian coast in March 1917. It was reported that the German destroyers had slipped their cables and had gone outside Ostend and Zeebrugge during an air raid. Four C.M.B.s, under the command of Lieut. W. N. T. Beckett, with the destroyer Falcon in support, went out in weather that was troublesome to the tiny craft. The C.M.B.s found four German destroyers at anchor and attacked with torpedoes. They hit one of the enemy and turned to escape. Lieut. Beckett was in trouble with a broken exhaust, and his boat was full of fumes and gas, but Lieut. Harrison fared worse. The engines of Lieut. Harrison’s boat failed, and for five minutes she lay in the glare of a destroyer’s searchlights under heavy fire, while the motor mechanic toiled to restart the engines. He succeeded, and the boats returned to Dunkirk with their crews exhausted but triumphant.

The Germans sent nine destroyers and six large torpedo boats on the night of March 21, 1918, to bombard the French coast. The attack was to synchronize with the great German offensive by land. British and French vessels had cleared out of Dunkirk Harbour to avoid an air raid. The Germans intended to shell the coast for half an hour, but the British and French destroyers slipped their cables and attacked, putting the German vessels to flight in ten minutes and inflicting loss. Only one coastal motor boat was available, C.M.B 20, and she steered for Ostend, hoping to get in a blow when the enemy made for that harbour. Lieut. Willett saw five destroyers and pressed on to within 600 yards before he fired. His torpedo hit the fourth destroyer. He did not see the result, for he turned and put up a smoke screen to hide himself from the terrific fire of the enemy.

During the raids on Zeebrugge and Ostend in 1918, the C.M.B.s played an important part. With the motor launches they had to put up smoke screens, show the way in for the block-ships by lighting flares, use their torpedoes inside the enemy harbours, and bombard the defenders with Stokes guns and Lewis guns.

Safety in Speed

Thebe were two raids. The first took place at Zeebrugge and Ostend in the early hours of St. George’s Day, April 23. The second raid was on Ostend in the early hours of May 10. Sir Roger Keyes (then Vice-Admiral and later Admiral of the Fleet) paid tribute in his dispatches to the work of the officers and ratings of the C.M.B.s, and many received awards. In the first raid twelve boats from Portsmouth and twelve from the Dover Patrol were detailed, eighteen for the raid on Zeebrugge and six for Ostend.

At Zeebrugge nine C.M.B.s were detailed to attack the Mole and the enemy vessels inside it, and eight for smoke screens and rescue work. Directly the boats ran in close to lay the smoke screen, they came under a heavy fire. Their speed and small size saved them, although shells sank many smoke floats and a change in the wind prevented the smoke screen from being as effective as intended.

ON TRIAL. A 55-ft. Thornycroft coastal motor-boat undergoing trials in the Thames estuary. Boats of this modern design have been supplied to a number of foreign navies. With a guaranteed speed of 40 knots, they carry two 18-in. torpedoes, depth charges and smoke screen apparatus, and have Lewis guns for protective purposes. They are also fitted with wireless. The boats are propelled by two Thornycroft 12-cylinder engines which develop about 450 brake horse-power. Each boat has, in addition, a cruising engine of 30/70 brake horse-power which will give a speed of about seven or eight knots.

One boat was late. She had fouled her propellers on the outward voyage and was towed into Dover. When the propellers had been cleared, she went to Zeebrugge and joined the smoke-float patrol.

Within the Mole C.M.B. 5 torpedoed a destroyer, hitting her below the forward searchlight and extinguishing it. C.M.B. 7 torpedoed a destroyer alongside the Mole and C.M.B 32 A fired a torpedo at the Brussels, Captain Fryatt’s former ship.

At Ostend the first raid was not effective. The Germans had shifted a buoy, and the two blockships went aground. During the combined operations the only casualties among the C.M.B. personnel were six wounded.

During the second raid on Ostend in May, C.M.B 25 escorted the Vindictive close up to the harbour entrance with a smoke screen, assisted her with guiding lights, torpedoed the piers, and opened up with Lewis guns on the enemy machine guns. Her commander was wounded and her acting chief motor mechanic was killed, but the C.M.B.’s second-in-command brought her out safely and a motor mechanic kept the engines running. C.M.B.s 24 and 30 torpedoed the ends of the piers and laid smoke screens close inshore. C.M.B. 26 left the Vindictive and torpedoed one of the piers at such short range and in water so shallow that the boat’s engines were damaged and her seams opened. She began to sink, but the leak was stopped. The engines restarted, and she got out of range and was taken in tow. C.M.B. 22 came under the searchlight and fire of a torpedo boat but, attacking with her Lewis guns, she drove the torpedo boat away and prevented her from interfering with the blocking operation. C.M.B. 23 escorted the Vindictive close inshore, and when the blockship gave the “last resort” signal, she lit the million candle-power flare and enabled the Vindictive to complete her work.

Later, in August, 1918, the coastal motor-boats were engaged in one of the fastest actions ever fought at sea. Six boats from Harwich were attacked by eight enemy aircraft near Terschelling, an island north of the entrance to the Zuider Zee. The motor-boats were speeding at over thirty knots and the aeroplanes at about eighty miles an hour. The aeroplanes dropped bombs and opened fire with their machine-guns. The boats replied with their Lewis-guns. One aeroplane was brought down, but in about half an hour four more aircraft, each carrying two machine guns, reinforced the enemy. The ammunition of the C.M.B.s was running low. Realizing this, the aeroplanes swooped low and, although one was brought down in the final bursts of fire from two boats, they had the boats at their mercy and riddled them with bullets. Three boats were sunk. One managed to reach the Dutch coast and two were taken in tow by a Dutch torpedo boat. Not one boat got back to Harwich. One wounded officer, Lieut. Lewis, after his boat had sunk, kept a fellow officer afloat on a fender for two hours and saved his life.

Because of their high speed and light draught the C.M.B.s were employed to lay mines. They had to pass over enemy minefields, where an ordinary mine-layer would have been blown up. They were always in the lion’s mouth, but they could not submerge and hide in the same way as the submarines. Their only defence was speed and smoke screens. They were so useful that the cruiser Diamond was fitted out as a C.M.B. Carrier.

A 70-FT. COASTAL MOTOR TORPEDO BOAT. This was an alternative design produced during the war. Boats of this type carried either torpedoes or mines. Coastal motor-boats made highly efficient mine-layers. Their shallow draught enabled them to pass over enemy minefields in safety and, because of their high speed, they were able to approach enemy waters unexpectedly.

After the Armistice of 1918 the base at Dunkirk was closed and the boats at the British bases were handed over to maintenance parties. But the work of the C.M.B.s was not over. Six 40-ft. boats were in the Eastern Mediterranean. These were sent through the Dardanelles to Batum and thence by railway to the Caspian Sea, as reinforcements for the commercial vessels that had been fitted out as gunboats to support the Russian loyalists. Six other boats were sent out, under the command of Commander Robinson, V.C., with several of the original C.M.B. officers. These were put on a train at Batum for the journey of 600 miles overland to Baku. The British officers had to work the train to a great extent. They had great difficulty in distinguishing between friendly and enemy Russians, and in preventing either from appropriating stores and gear.

Two steamers were fitted as carriers, and the C.M.B.s were kept at sea ready to attack the Bolshevist Fleet. They caused a number of vessels to surrender by exploding depth charges near them, although the choppy water made conditions difficult for the high-speed boats. When the operations in the Caspian concluded, the British officers were sent home and the boats were handed over to friendly Russians.

The effective Lewis-gun fire of the C.M.B.s and their handiness in close-fighting, suggested their use in the British force that was sent to Archangel in 1919. A flotilla of 55-ft. boats was sent to operate as floating batteries of Lewis-guns up the Dvina River, which flows into the White Sea at Archangel. It was considered that the shallow water would prevent the use of torpedoes; but that the speed and light draught of the boats would enable them to go farther than any other type of fighting craft.

Every boat was equipped with six Lewis-guns and portable bulletproof shields. They arrived at Archangel and proceeded up the Dvina with their parent ship, H.M.S. Hyderabad. This vessel was a special light-draught ship built during the war as a decoy ship for U-boats. The expedition was impeded by the shallowness of the water and by the large number of mines. On one occasion a monitor went aground and was in danger of being struck by floating mines until C.M.B 34 towed her off.

Long distances were covered by the motor boats - the trip from the front down the river to Archangel and back amounted to 500 miles - but the engines were so well built and tended that they ran for about three times the usual period without overhaul. The British force was eventually withdrawn. Probably the most successful feat of a C.M.B. acting without support from other vessels was the sinking of the Russian cruiser Oleg, by Lieut. Agar, who was awarded the V.C. This occurred during the British blockade in the Baltic that was to prevent the Bolshevist Fleet from coming out of Petrograd (now Leningrad) Bay.

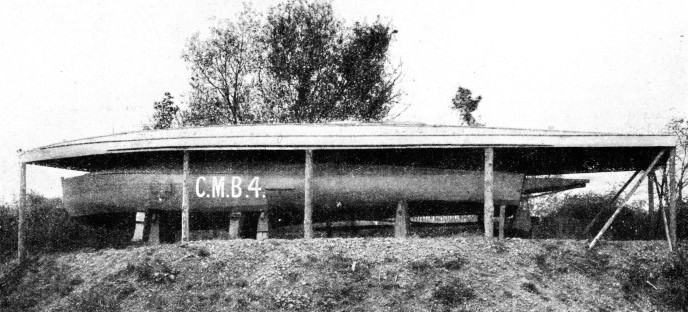

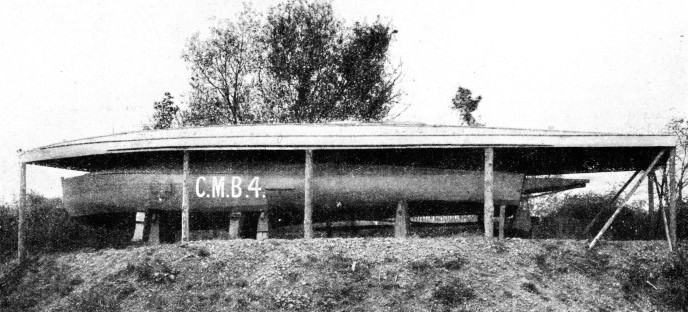

The Oleg was anchored outside Kronstadt in Petrograd Bay, with a screen of four destroyers. Attacking at dawn with the 40-ft. C.M.B. 4, Lieut. Agar evaded the destroyers and dashed in close to the Oleg His solitary torpedo exploded in a vital part of the cruiser and sank her.

The Gauntlet of Guns

This brilliant stroke made the Admiralty decide to send eight 55-ft. C.M.B.s. It was impossible for large vessels to attack Kronstadt with any hope of success, but it was considered that the C.M.B.s stood a chance of getting inside the harbour. After the loss of the Oleg, the Bolsheviki did not risk leaving a large vessel outside the harbour. They kept the big craft well inside, and deputed a destroyer to guard the entrance.

Photographs taken from aeroplanes showed the positions of the ships, and a plan of operations was prepared. An air raid was timed to coincide with the attack by the C.M.B.s. Eight boats, 86 BD, 72 A, 79 A, 31 BD, 88 BD, 24 A, 62 BD, and the 40-ft. C.M.B. 4, with Lieut. Agar, V.C., took part. The boats moved off from H.M.S. Vindictive and started about 10 p.m. on August 17,1919. The sea was calm and the night dark. Lieut. Bremner, in command of 79 A, the first boat in, torpedoed the submarine depot ship, Pamiat Azov, but his boat was disabled immediately afterwards. Close on his stern were 31 BD, Lieut. McBean with Commander Dobson, and 88 BD, Lieut. Dayrell-Read.

As 88 BD was coming through the entrance, Lieut. Dayrell-Reed was shot through the head and killed. Lieut. Steele took command and torpedoed the battleships Andrei Pervozvanni and the Petropavlovsk.

At about this time Lieut. Agar in C.M.B. 4 arrived with the remaining boats. Lieut. Napier, in 24 A, fired a torpedo at the flotilla leader anchored outside the harbour, but his boat was afterwards sunk.

Lieut. Brade, in 62 BD, arrived at the harbour, after 88 BD and 31 BD had left, although 79 A was still inside, disabled. No sooner had 62 BD entered than she, also, was disabled. The two crippled boats were got outside by heroic efforts. Lieut. Agar, in C.M.B. 4, waited outside the harbour to torpedo any ship that came out.

On their way out the boats had to run the gauntlet of the guns and searchlights of the forts.

The action was the most brilliant ever fought by C.M.B.s. Two battleships and a submarine depot ship were sunk and other enemy ships were damaged. The C.M.B. losses were slight in comparison with the damage that they inflicted on the enemy vessels.

AN INTERESTING RELIC of the Allied campaign in Russia. Coastal Motor-Boat 4, commanded by Lieut. A. W. S. Agar, V.C., D.S.O., sank the Russian cruiser Oleg while she was at anchor outside Kronstadt Harbour acting as guard ship, Lieut. Agar succeeded in avoiding the four destroyers that formed a protective screen for the Oleg and torpedoed the ship at short range. She was hit in a vital part and sank at once. The photograph shows C.M.B. 4, now preserved in Thornycroft’s yard at Hampton-on-Thames.

You can read more on “Epic of the Motor Launches”, “Greyhounds of the Fleet” and

“The Navy Goes to Work” on this website.