© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Epic of the Motor Launches

The Motor Launch Patrol included 550 Motor Launches manned by officers and men of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. In the successful raids on Ostend and Zeebrugge the dramatic exploits of the MLs gained for these small craft a permanent place in naval history

THE DOVER PATROL was originally formed during the war of 1914-

THE work of the Motor Launch Patrol in the war of 1914-

Their part in the raids on Ostend and Zeebrugge is secure in the records of actions fought according to the traditions of Drake and Nelson, but the unspectacular patrols in fair weather and foul are forgotten, except by the men who manned these wooden craft.

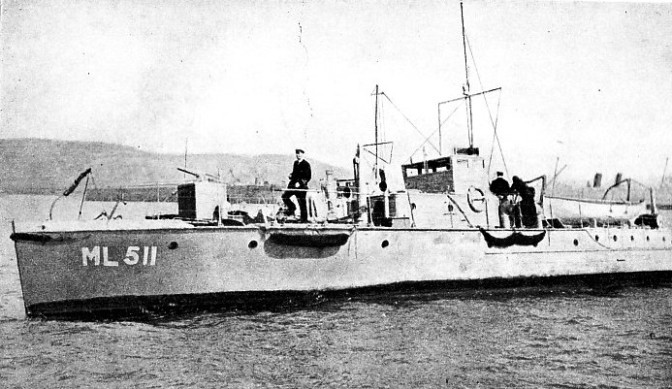

Although they were mass-

They were powered by two 220-

The crew were crowded into a small forecastle; alt of it was the magazine, then the chart-

They came into being as a fleet. Mr. Henry R. Sutphen, an American boatbuilder, met a British shipbuilder who was in New York on Admiralty business early in 1915 and suggested a fleet of motor launches for anti-

After the first batch of fifty boats had been delivered the St. Lawrence River was closed by ice, but the Admiralty wanted to test the boats during the winter at Halifax, an ice-

The M.L. fleet reached Great Britain in the summer of 1916. Before it arrived patrol work had been carried out by members of the Motor Boat Reserve in a hotch-

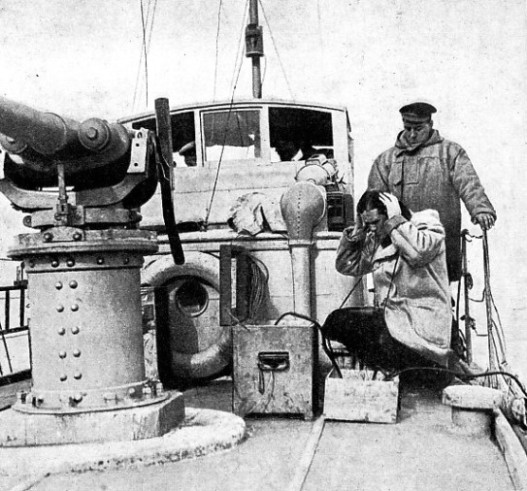

Because of their number, small size and light draught the M.L.s became useful little ships. Large patrols operated from the bigger ports, and smaller patrols were based on little harbours too small to berth even a destroyer. Drawing less than 4 feet, they were virtually safe from a torpedo, and their speed and small size made them difficult targets for submarines. Their guns and Lewis guns gave them the chance to hit back and force a submarine to submerge. Once a submarine was down the M.L.s came up at full speed and dropped their depth charges. On patrol they listened with hydrophones for submarines, their own engines having been stopped.

Although the M.L.s could not face such dirty weather as the destroyers and armed trawlers, they patrolled in rough water in the depth of winter. So unstable that they would roll the heart out of a rocking-

Able to operate at speed in water little deeper than an ordinary swimming bath, the M.L. was particularly useful in shoal-

In the Mediterranean, in addition to anti-

The Navy is frequently referred to in terms of floating fortresses which fight an enemy fleet miles away, and it has not been realized that the tiny M.L.s sometimes went within a stone’s throw of the enemy, just as Nelson had done, and against odds as great. The daring adventurers in these floating matchboxes were often lucky enough to emerge with their lives. Perhaps it was not so much luck as the just reward of taking the boat into a place where the enemy never imagined that a boat would reach.

One great feat of that nature was achieved by M.L.196. She went at night into the Turkish harbour of Sivriji in search of an enemy submarine reported to be there. Inside the harbour the searchlight of the M.L. was switched on and swept the harbour, but the submarine was not there. Then the searchlight was switched off, but the M.L. fouled an obstruction and became a fixed target for the Turks until she floated clear and wriggled out of the harbour to safety.

No job was too big for the little boats to tackle, and they were indispensable servants of bigger vessels. Without them and their smoke screens the raids on Ostend and Zeebrugge would not have been possible. Their task was to blind the enemy shore batteries and searchlights by setting up curtains of smoke, and to take the men off the blockships. This meant they were the first in and the last out of danger.

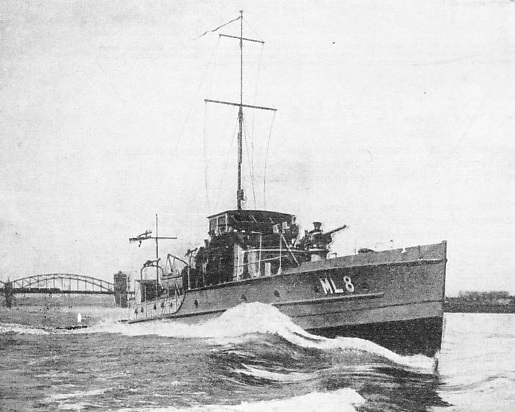

M.L.S ON THE RIVER RHINE. Two petrol motors of 220 horse-

The first raid on St. George’s Day, 1918, took place simultaneously at Zeebrugge and at Ostend. No fewer than sixty-

Before the raid could be attempted an efficient method of making smoke had first to be devised. This was done by Wing-

Before the final attack there were two false starts, abandoned owing to unsuitable weather. The third attempt was more fortunate. One section went to attack Ostend while the other concentrated upon Zeebrugge.

At Zeebrugge the small craft laid the smoke screen and a favourable wind blew the smoke towards the shore as the Vindictive headed for the Mole. The wind then dropped and next changed to south-

Three blockships, Thetis, Intrepid and Iphigenia, came under a hot fire as they rounded the Mole. One M.L. was behind the Thetis and another behind the Iphigenia. The Thetis did not reach the entrance to the canal as her propellers fouled the nets that were part of the defences. She dragged the nets with her until they stopped her engines, but she pulled them far enough out of the way to enable the other two blockships to pass.

She was sinking when her commander ordered her to be abandoned and prepared to sink her. The boats were picked up by Lieutenant Hugh A. Littleton in M.L.526, and then the M.L. waited for the last boat containing the men who had fired the charges.

Heroism at Zeebrugge

Crammed with some sixty men, in addition to her normal complement, M.L.526 made her way to sea unmarked except for a machine-

The second launch, M.L.282, had an exceptionally hazardous experience, but her commander, Lieutenant Percy T. Dean, was equal to every emergency and did such gallant work that he was awarded the V.C. When the Thetis was stuck outside the entrance to the canal the blockship directed the two others. The Intrepid went into the canal first and swung into position while the Iphigenia followed. The M.L., which was close under the stern of the Iphigenia, went right into the mouth of the canal where Lieutenant Dean waited along the western arm and set up a smoke screen in the hope of saving the two ships from punishment.

Lieutenant Stuart S. Bonham-

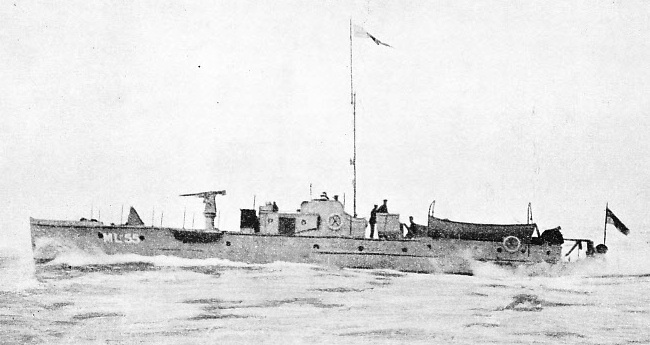

THE MOTOR LAUNCH FLAGSHIP OF THE DOVER PATROL was M.L.55 flying the broad pendant of Commander Sir Ion Hamilton Benn, R.N.V.R. Commander Benn was in command of the M.L.s during the raids on Ostend. In M.L.532, when blinded by smoke, he crashed into the bows of the blockship Brilliant. Both engines of M.L.532 were put out of action, but one was later set going, and the little vessel managed to escape to sea, where she was taken in tow by another M.L.

Heavy machine-

The set plan of any attack such as the Zeebrugge raid inevitably goes to pieces with the firing of the first shot. From that point everything depends on the courage, resource and discipline of the officers and men of each unit. As the Zeebrugge raid occupied a hundred minutes and the whole area was a raging inferno, it was a supreme test. Young officers had to think and act quickly when they saw things were not going according to plan.

Lieutenant Gordon S. Maxwell, in M.L.314, found on dropping a smoke buoy that the enemy immediately concentrated fire upon it. He decided to draw the enemy fire to ease the pressure elsewhere. He took his M.L. to within 500 yards of the beach, waited until a searchlight found her, then dropped the first of several smoke buoys, having first removed a plate which caused every buoy to show a bright light instead of none. Then the M.L. scurried out of the way. Puzzled by the lights and possibly fearing an attempt at a landing, the Germans opened a heavy fire on these floats.

Not all the M.L.s were lucky. Lieut.-

but also to the canal, with calcium buoys. When the vessel was approaching the entrance she was hit by three shells which killed and wounded half the crew and destroyed the engines. Hit in three places and mortally wounded, Lieut.-

The “Iris” Saved by an M.L.

Another M.L., M.L.424, was sunk off the Mole, and the survivors were rescued by a sister ship. These two M.L.s were the only ones lost in the Zeebrugge raid, although one, which had been in collision in the smoke screen, returned to Dover little better than a wreck.

M.L.558, commanded by Lieut.-

The M.L.s at Ostend were under the command of Commander Ion Hamilton Benn in M.L.532. The first attempt to seal Ostend was not successful and, but for the rescue work done by the M.L.s, the casualties would have been much heavier than they were. The two blockships, Brilliant and Sirius, stranded eastward of the canal entrance and were blown up.

Commander Benn’s M.L.532 was blinded by smoke and smashed her bows against the Brilliant, but by the efforts of all on board she was kept afloat. Both engines were put out of action by the force of the collision, but one engine was got going again, and she crawled out to sea, where she was taken in tow by another M.L.

After M.L.532 was out of action, M.L.276, Lieutenant Roland Bourke, and M.L.283, Lieutenant Keith R. Hoare, took over the rescue work, for which they received the D.S.O.

BUILT IN NORTH AMERICA, 550 M.L.s were sent across the Atlantic to Great Britain. Of these, fifty had a length of 75 feet and the remainder a length of 80 feet. They had a beam of about 12 feet, and were armed with a gun forward, depth charges aft, a Lewis gun, lance-

The work at Ostend was all the more difficult, because at the critical moment the wind changed and spoiled the smoke screen. When it was discovered that the Germans had shifted the Stroom Bank Buoy, the Germans put up a counter smoke screen which prevented the British ships from establishing their position and so blocking the canal.

A second attempt was made to seal the harbour of Ostend in the early hours of May 10, 1918, when the immortal Vindictive was placed in position and sunk. It was intended to sink the Sappho in addition to the Vindictive, but the Sappho had a boiler accident on the way and did not arrive in time.

The previous raids on Ostend and Zeebrugge had warned the Germans, and new tactics had therefore to be evolved. These placed more responsibilities upon the small craft, as it was decided that there should be no preliminary bombardment. This time the wind was better for the smoke screens. The work of the coastal motor boats in laying the preliminary screens and lighting the way for the Vindictive described in the chapter “Coastal Motor Boats”. The M.L.s also laid smoke screens, to such good effect that the Vindictive was hit only by shrapnel on her way to the harbour entrance.

Upon the M.L.s fell the work of jetting the heroes of the Vindictive, awav after their job was done.

Any attempt to describe the heroism of the two officers who were awarded the V.C. for their work with the M.L.s be based upon the official dispatches of Sir Roger Keyes. The two officers were Lieutenant Geoffrey H. Drummond and Lieutenant Roland Bourke. Lieutenant Bourke was in the same M.L.276 in which he had done such splendid work at Ostend on St. George’s Day. He volunteered for the second raid. Here is the official dispatch of Sir Roger Keyes concerning Lieutenant Bourke:

“Volunteered for rescue work in command of M.L.276, and followed Vindictive into Ostend, engaging the enemy’s machine-

“During this time the motor launch was under heavy fire at close range, being hit in fifty-

Rewards for Valour

This is the terse record of Lieutenant Geoffrey H. Drummond:

“Volunteered for rescue work in command of M.L.254. Following Vindictive to Ostend, when off the piers a shell burst on board, killing Lieutenant Gordon Ross and Deckhand J. Thomas, wounding the coxswain, and also severely wounding Lieutenant Drummond in three places. Notwithstanding his wounds, he remained on the bridge, navigated his vessel, which was already seriously damaged by shell fire, into Ostend harbour, placed her alongside Vindictive and took off two officers and thirty-

There was such an inferno at Ostend when the battle opened that the full details will never be assessed. A brave and just commander such as Sir Roger Keyes does his best when apportioning the awards for valour, but many incidents are hidden by the smoke screens and by death. Many of the men had been through the ordeal of the first raid, so they knew what they might expect the second time.

Commander Benn, D.S.O., the commander of the flotilla, was. awarded the C.B., and Commander William W. Watson, who was in command of the flagship, M.L.105, the D.S.O. Lieutenant Keith R. Hoare, D.S.O., D.S.C., of M.L.283, received a bar to his D.S.O., and Lieut.-

Afte r the war the M.L.s were sold, and many were converted into motor yachts by private owners.

r the war the M.L.s were sold, and many were converted into motor yachts by private owners.

USING A HYDROPHONE. Some motor launches were equipped wit' hydrophones, which made it possible to listen for German submarines in the vicinity Their shallow draught and fast speed made M.L.s almost immune from submarine attacks. The M.L.’s armament would force the submarine to submerge and then depth charges would be dropped over the spot.

You can read more on “Coastal Motor Boats”, “Epics of the Submarines” and “Hazards of the Sea” on this website.