The sailing vessels that were used as trap-ships and decoys during the war of 1914-18 were even more exposed to peril than many of the steamers. Sailing ships were frequently at the mercy of winds and tides, and it was more difficult for them to conceal their identity

MYSTERY SHIP ADVENTURES - 3

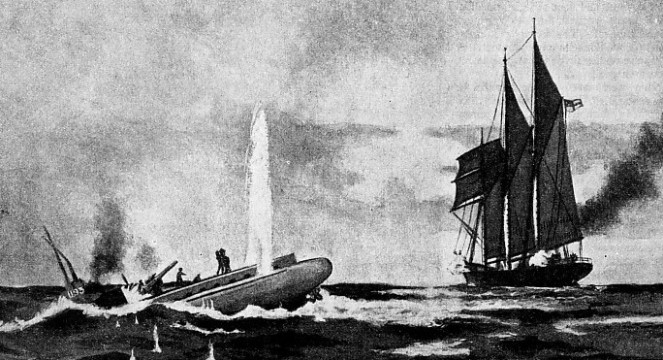

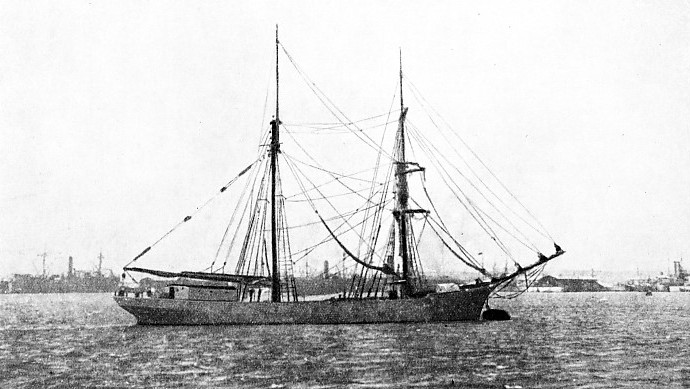

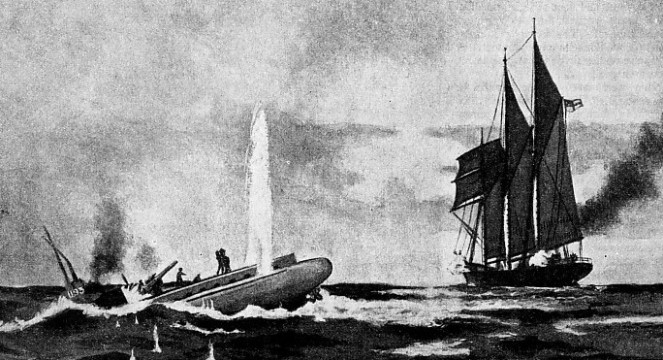

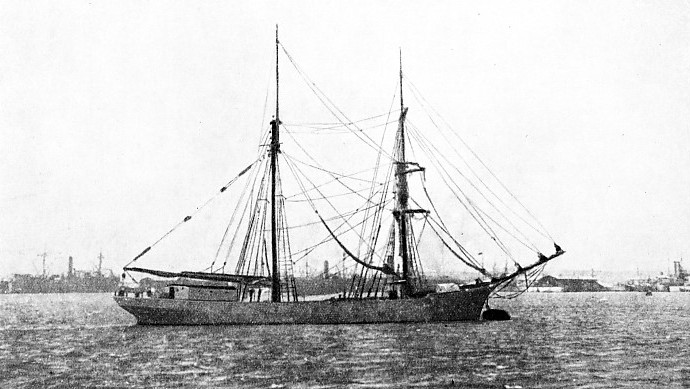

“DOWN SCREENS! OPEN FIRE.” Not until the decoy sailing ship Prize (Q 21) had been shelled by the German submarine U 93 for twenty minutes did an opportunity occur for Lieut. W. E. L. Sanders to run up the White Ensign, expose the two 12-pounders of the schooner and fire. His first shot was fired at 9.5 p.m. on April 30, 1917, and in a few minutes U 93 was apparently sunk. Formerly the German topsail schooner Else of 199 tons, the Prize had a length of 112 ft. 6 in. She was the first prize captured by the Royal Navy in the war of 1914-18.

UNTIL the war of 1914-18 a good deal of the coasting trade round the British Isles was carried on by schooners, brigantines and barquentines averaging about 200 tons. They were always a picturesque sight, though commercially they had their defects, as they depended so much on wind and weather. Modern progress demands greater reliability and more regard to punctuality, so that the small steamers and the big motor barges have almost driven the sail-carriers out of the trade. Thus the sight of a schooner cargo vessel turning to windward down the English Channel under reefed canvas is now somewhat rare.

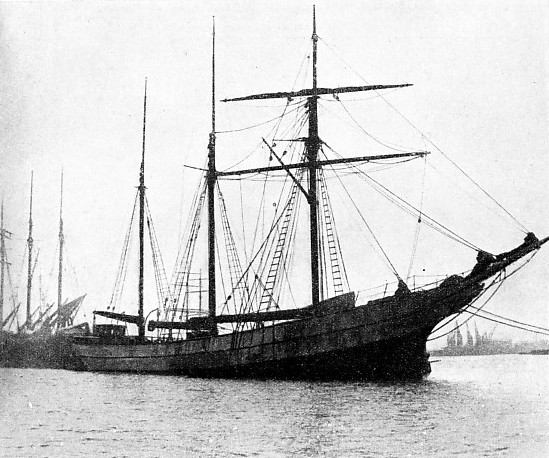

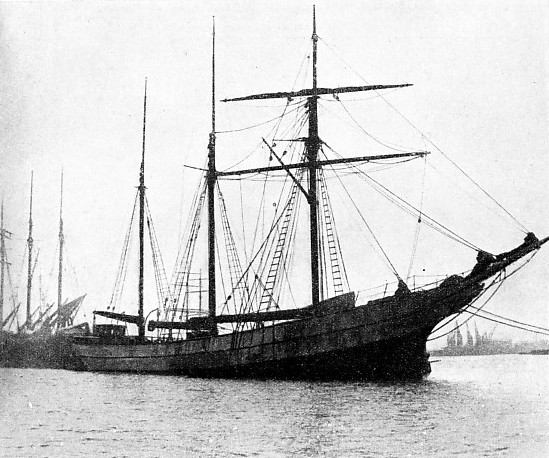

Our story opens in July 1916, when the brigantine Helgoland was lying in Liverpool. British owned, this 310-tons sailing vessel had been built of steel and iron in 1895 at Martenshoek (Holland). The summer of 1916 was a period when enemy submarines, and

their antidote the decoys, were receiving considerable attention. Since the sailing coasters were still at work along the English Channel and off the Irish coast, it was suggested that they should be experimentally armed as “trap-ships” and sent to sea with picked crews.

The Helgoland was selected and armed with four 12-pounders as well as one Maxim gun. She changed her name more than once, being thenceforth known under the aliases of Horley, Q 17, and Brig 10. Her commanding officer was Lieut. A. D. Blair, Royal Naval Reserve, who disguised himself as a coasting skipper. Sub-Lieut. W. E. L. Sanders, also R.N.R., who had much experience in sailing ships, became the Helgoland’s mate. The rest of the crew comprised a trawler skipper who in peace-time had been a fisherman; nine more men who also had served in trawlers; one carpenter, one steward and one cook, who all belonged to the Mercantile Marine, and two petty officers and six gunnery ratings of the Royal Navy.

On September 6, 1916, the Helgoland sailed from Falmouth (Cornwall) on her first warship cruise, bound for Milford (Pembrokeshire). Her departure took place after dark, to preserve secrecy. She had not long to wait. On the following day, when ten miles south of the Lizard (Cornwall), she sighted a submarine. Within five minutes the submarine began shelling the Helgoland at 2,000 yards range, the gunnery being so excellent that the first German shell fell only ten yards short.

In normal times the Helgoland would have carried only a small crew. To avoid suspicion, therefore, in the circumstances, it was essential that the greater part of her personnel should remain hidden. Under Sub-Lieut. Sanders’s supervision the fighting men crept unseen to their stations immediately the alarm bell had been sounded, but the screens concealing the guns were not to be dropped till the critical last minute. By bad luck the weather happened to be exceptionally fine. It was one of those late summer days when the wind dies utterly away. The brigantine thus lay becalmed and unable to manoeuvre. The conditions were ideal for a U-boat attacking on the surface from a safe position.

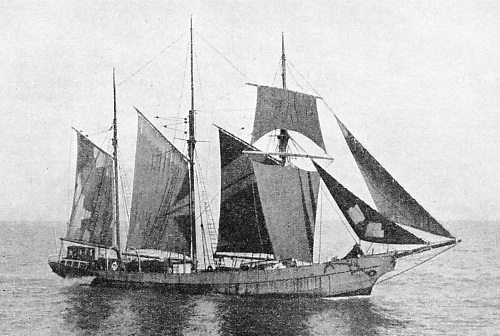

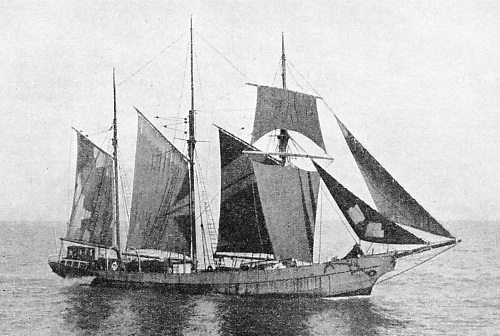

ONE OF THE MOST SUCCESSFUL Q-SHIPS was the Mary Mitchell, a three-masted topsail schooner of 210 tons. She was built at Carrickfergus, Co. Antrim, in 1892, and was registered at Beaumaris, Anglesey. The Admiralty took her over during the war of 1914-18 and she operated from Falmouth, Cornwall, fitted with a collapsible gun-house on her poop. On December 2, 1916, she sank U 26 and on June 30, 1917, she sank two more submarines in the Bay of Biscay.

The enemy wasted no time in getting on to the target, for her second and third shots struck the Helgoland’s foretopsail-yard. After the second shell Lieut. Blair, finding the brigantine’s guns would just bear, let down his screens and opened fire. The fourth shell dropped so near that , the submarine quickly dived. Two hands were then sent aloft to keep a look-out. A few minutes later a periscope was seen 200 yards away, but disappeared after the sailing ship had fired two shots.

Half an hour later a larger submarine appeared. This was not unusual, since U-boats often hunted in couples, especially in such busy areas as the waters off the Lizard and the Scillies. What was unusual, however, was the fact that the second submarine had a sail set aft about the size of a drifter’s mizen. At a distance this had the effect in certain atmospheric conditions of disguising the enemy’s character. I recollect another submarine attempting a similar disguise that summer off the south-west coast of Ireland.

Lieut. Blair attacked again, but the enemy received such a surprise that she made a quick smoke-screen and dived. One of these two visitors evidently remained in the neighbourhood, for at dusk — about 7 p.m. — the sound of a submarine’s motors was heard, and just before 9.30 p.m. a U-boat could be seen ahead. The calm still continued and, although her new foretopsail was set, the Q-ship could not be steered to let the guns bear. Finally, about 10 p.m., since absence of any breeze made the game impossible, the Helgoland spoke an armed trawler which towed her back into Falmouth. Now, Blair’s ship — which was 122 ft. 9 in. long and 23 ft. 3 in. Beam — luckily drew only 8 feet aft. While the Helgoland was communicating with the trawler the persistent submarine fired two torpedoes which passed right under the brigantine amidships. With a foot or two more draught the decoy would have been blown up.

From this disappointing and indecisive brief cruise it was obvious that the Helgoland needed an auxiliary motor; otherwise light airs and flat calms would make manoeuvring impossible. Her next encounter happened on October 24, about twenty miles southwest of the Lizard. This time there was a breeze from the south-west, so that she went bowling along on an E.S.E. course over a moderate sea. On this occasion she was commanded by Lieut. G. G. Westmore, R.N.R., and at 6.20 a.m. her next adventure began. About a mile away on the starboard bow and steering a westerly course down Channel, was noticed the large tramp steamer Bagdale; chasing the tramp was a submarine. Westmore steered closer to the wind to intercept the enemy, but at 6.42 the U-boat opened fire on the Baqdale. Once again the enemy had attempted some disguise by using a sail; once again the Helgoland went into action.

UNDER MANY NAMES the Mary B. Mitchell had an adventurous and successful career. Known variously as the Mitchell, Mary Y. Jose, Maria Therese and by other names, she nearly came to disaster by storm in January 1917. With five concealed guns she left Falmouth as the neutral Mary Y. Jase of Vigo, Spain. The storm carried away her foremast and mainmast, but eventually she was taken in tow off Ushant by the Norwegian steamship Sardinia.

The screens were dropped and the starboard guns fired. Their second and third shots seemed to reach the enemy amidships. For she stopped to fire only one round and then dived. But, as had happened on September 7, a second submarine now appeared. The newcomer, painted a lighter colour though without a sail, was seen two miles away, making for the Bagdale, whose crew had taken to the boats and abandoned ship. It was now 6.50 a.m. Westmore went about on the other tack and made towards the enemy in an endeavour to save the steamer.

The time was critical, but the range was as much as 4,000 yards. The Helgoland opened fire. She did not hit the submarine, but frightened her, causing her to dive out of sight. Certainly the German presently came to the surface, but did not remain there. She made off in a south-westerly direction and was not seen again. For the next two hours the brigantine kept tacking about the Bagdale ready to shell the U-boat, which had been expected to return. Shortly after 9 a.m. two steam trawlers were seen and signalled. They picked up the boats and then towed the Bagdale into Falmouth. Thus was seen this autumn morning the unusual sight of a sailing ship saving a steamer ten times her own size. For the Bagdale was of 3,045 tons and was a valuable Admiralty transport.

Some months later the Helgoland had another adventure, but the location was off the Irish coast — eight miles north of Tory Island, Co. Donegal. A submarine attacked her by gun at 7.25 a.m., and after half an hour hit the brigantine’s after gun-house, killing one man, wounding four and stunning all the afterguns’ crews. But the brigantine shelled the enemy till she escaped by diving.

Submarine Under Sail

The date of this engagement was June 9, 1917. Two days later the Helgoland had returned to the region of the Scillies, where once more a submarine was found under sail. In some ways the Helgoland never had the luck she deserved, for July 11 was another calm and hazy summer day. She was drifting with the tide, when enemy shells flew over the fore-t’gallant yard. Motors were then started. At 500 yards the guns came into action, and the submarine probably received injuries, but she escaped by diving.

The Helgoland survived the war and I came across her quite by accident at anchor in a lonely Cornish creek. No one was on board and she seemed somewhat unkempt. Though she had long since yielded up her armament and had resumed trading, freights were bad, she lay idle, and a strike was holding things up. What seemed so pathetic was that this heroine of many duels should be completely ignored; even the local seafarers had to be reminded of her identity.

Few people fully realize the manifold difficulties of life aboard these mystery sailing ships. More lively in a sea-way than the decoy steamers, they were rarely on an even keel. Frequently at the mercy of winds and tides, and much more difficult to handle tactically, they were far less easy to disguise. Indeed, with no funnels to repaint, no superfluous masts to unrig, no false steam-pipes, no bridge to modify, and no well deck to fill in, they could scarcely change their appearance anew after engagement. Thus, having once disclosed their identity and allowed an enemy to get away, the sailing man-of-war became marked out.

There was, moreover, always the possibility that, despite all the rehearsals, some unfortunate mishap might spoil the whole make-believe. In the action of October 24 the Helgoland was just about to drop all disguise and begin operations, when the screen concealing her armament jammed. This might have delayed action fatally had not Sub-Lieut. Sanders come to the rescue and cleared it. Similarly, on the afternoon of July 10, 1917, the decoy auxiliary schooner Glen (alias Sidney) must have done something which no amount of practising could prevent. She found herself in the presence of a UC-boat, and had played the role of innocence so perfectly that the “panic party” had gone off without a hitch, while the real fighting people remained on board and were about to “down screens”.

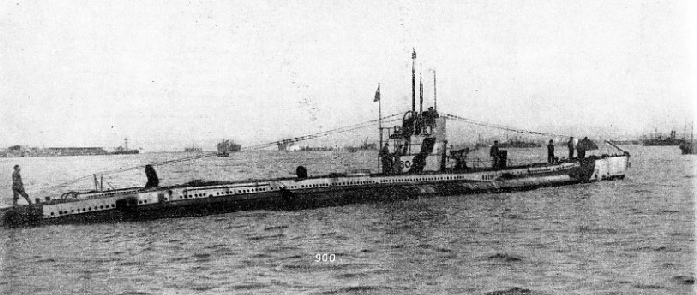

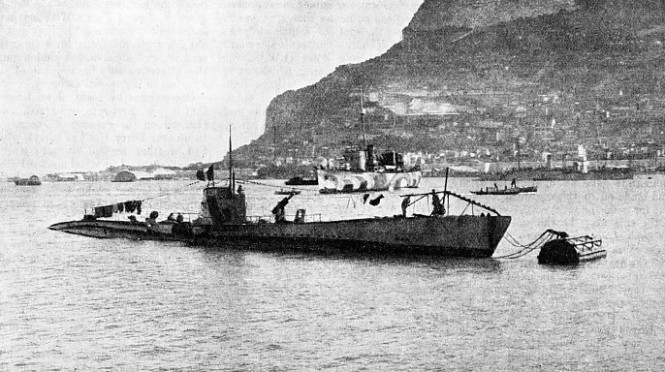

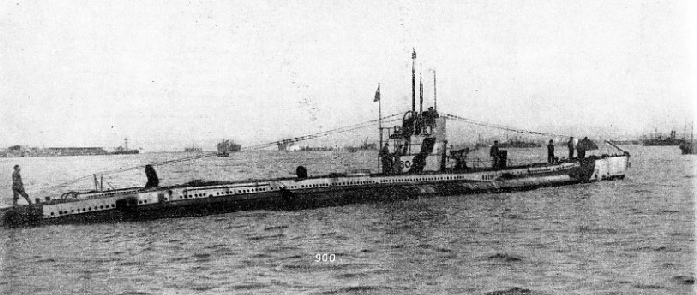

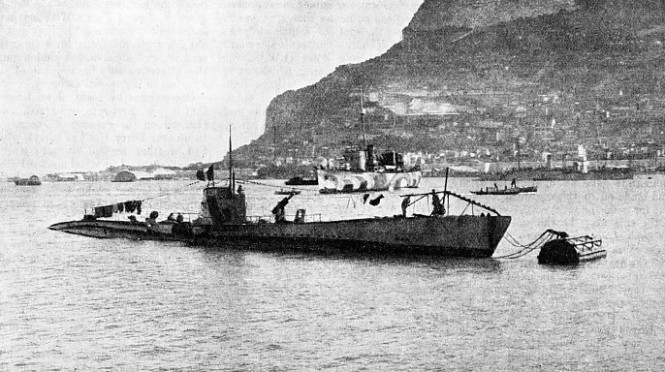

A GERMAN SUBMARINE AT GIBRALTAR before being surrendered to Italy after the war of 1914-18. This photograph shows UB80 similar to UB48 which, under the command of Lieut.-Commander Steinbauer, sank the British steamship Roanoke, 4,803 tons, on August 12, 1917. Three days later the heroic Q-ship Prize met her doom in a conflict with UB48.

The Glen’s captain anxiously watched his boat row away, and was waiting to open fire, when a German officer appeared in the conning-tower and hailed the oarsmen. Speaking good English, he ordered the boat alongside the submarine and the rowers proceeded to obey. Suddenly the whole situation became transformed. Whether the enemy caught sight of somebody’s head aboard the Glen, or whether some small detail of disguise ruined the perfect picture, cannot be precisely stated. But that German officer became so startled that he disappeared down the conning-tower. The hatch slammed and the submarine began to dive hurriedly; though not before the decoy had opened fire and had done her some damage.

This incident may be compared with one that happened a few weeks earlier. At 6 p.m. on May 17,1917, the Glen was thirty-five miles south of the Needles, She was foaming along close-hauled, steering to the north-east. Without the slightest warning there burst the sound of a gun, and five minutes later could be seen the flash as a second shell rushed forth. Next, about two and a half miles away to the southward, there appeared UB 39, which measured 121 feet long and mounted her 22-pounder just forward of the conning-tower. The Glen now began her play-acting as if she were a terrorized coaster. She backed her foreyard, and eased away all sheets to check way. The “panic party” ostentatiously began to make ready the ship’s boat for lowering.

An Unwelcome Eyewitness

The submarine, having ceased fire and partly submerged, with periscope and a portion of her conning-tower showing above surface, approached along the schooner’s starboard side, keeping 200 yards distant. The “panic party” were just in the act of “abandoning ship” when UB 39 most obligingly rose to the surface full of confidence only eighty yards away. The target was now almost at right angles. The schooner had an inferior armament — one 12-pounder and one 3-pounder — but within five seconds a shot from the larger gun boomed out and fell abaft the conning-tower. This took the enemy unawares and the head and shoulders of a man appeared as the conning-tower hatch opened. A second 12-pound shell burst just below the conning-tower on the hull, which caused the man to fall backwards down the hatch. The submarine now attempted a crash dive, but a third and fourth shot made more holes on the steel hull. Next the 3-pounder, firing, registered not fewer than four hits out of six rounds. Thus riddled, UB 39 listed badly and sank with all hands, sending up to the surface oil and bubbles as her final gasps.

This was a victorious occasion for the decoy’s captain, Lieut. R. J. Turnbull, R.N.R., whose quick-wittedness had turned defence into offence. But even now it was not possible to relax vigilance, for there had been an eyewitness of this battle, lonely though the seascape seemed. Almost immediately, and before the “panic party” could rejoin their ship, there appeared a second submarine bent on vengeance. She showed herself presently at 600 yards on the port bow, and the Glen fired at her. Then, while the schooner waited to pick up the rowers, the enemy appeared 1,000 yards off the port quarter. The evening’s excitement seemed now to have ended and, under sail with motor running, the Glen was heading to the north when again a submarine opened fire at 7.40 p.m. with two guns.

It is possible this may have been a third enemy; at any rate she was decidedly bigger than UB 39, and it is probable that the second submarine had wirelessed to the third submarine, telling her to head off this “trap-ship”.

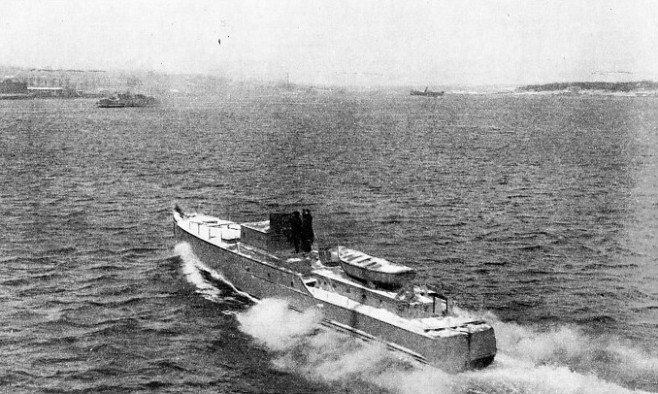

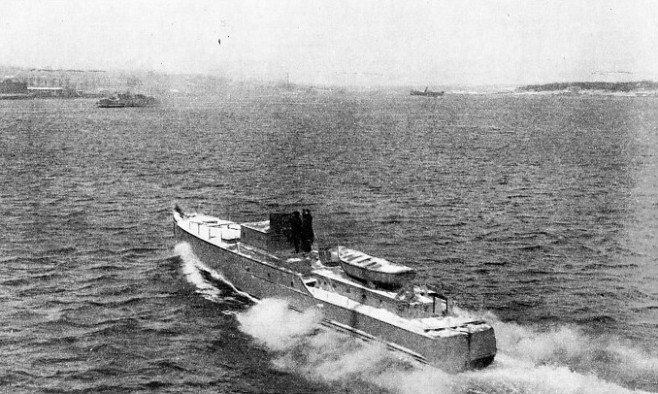

MOORED OFF GIBRALTAR, after the Armistice, the German submarine UC94. The decoy auxiliary schooner Glen (alias Sidney) encountered a UC-boat of this type on July 10, 1917. The Glen put off a “panic party” in an open boat as usual, but the Germans must have noticed something unusual. The submarine immediately dived, but not before the Glen had inflicted some damage.

The scene was of great strategic importance, because it was in the track of the liners bound for Southampton and London, and because the smaller steamers, with army supplies destined for Cherbourg, would reasonably be expected here. But the small schooner had upset the German ambush at this strategic point. At 8 p.m. the big submarine gave up fighting the Glen, and made off to the westward, looking out for easier prey.

On this May 17 the sailing vessel Florence Louisa (115 tons) was sunk eight miles south of the Needles (I.W.), and the next day the steamship Dromore (268 tons) was sunk six miles south of Guernsey. On May 20 two more sailing vessels, the Dana (182 tons) and the Mientji (120 tons), were similarly destroyed twenty-five miles north of Guernsey. But, evidently, warning of Turnbull’s schooner had been well circulated among U-boat captains, who did not wish to make the mistake that had finished UB 39.

On June 25, when again sailing between the Isle of Wight and the French coast, the Glen was shelled by another submarine which remained so cautious as to approach no nearer than 4,000 yards. This time the spot was a little closer to the English shore —fourteen miles south of St. Catherine’s Point (I.W.). The tactics of the rivals were much the same as before, yet the end might have been different. For the U-boat’s shell splinters damaged the schooner’s sails and bulwarks so seriously that, if the enemy had not submerged and departed after about a dozen rounds, she could have sunk the schooner.

Schooner of Many Aliases

There was no lack of thrills in these sailing decoys, but the excitements were not confined to fighting other craft. Whether in war or in peace, the sailor always has the treacherous sea for his foe, and the Mary B. Mitchell (alias Mitchell, Mary Y. Jose, Marie Therese, and other names) had an awkward experience during January 1917. She was a three-masted topsail schooner, owned by Lord Penrhyn, and of 210 tons. Registered at Beaumaris (Anglesey), she had been built at Carrickfergus (Co. Antrim) in 1892, and when taken over by the Admiralty during the war was in Falmouth with a cargo of china clay. Having been fitted out with guns and a collapsible gun-house on the poop, she left Falmouth as the neutral Mary Y. Jose of Vigo. With her radio aerial (cleverly concealed in the rigging), her gymnastic apparatus for keeping the crew fit, and her five well-hidden guns, this attractive ship became one of the smartest in her special category.

Commanded by Lieut. John Lawrie, R.N.R., a first-rate sailorman, she chanced on the evening of January 7 to be near Berry Head (Torbay), when bad weather worked up into a real winter’s gale. In normal circumstances she could have run for shelter with the choice of several anchorages; Q-ships, however, in their anxiety to preserve secrecy, tried to avoid entering ports and being asked awkward questions by pilots. Moreover, hard by there might be some genuine neutral, which would carry to Germany particulars (with photograph) of the mysterious ship.

So Lawrie kept the sea, and next day the gale blew without mercy. Shortly after 9.30 p.m. the night became more terrible and the foremast (with its yards) crashed down, carrying away also the mainmast, and leaving only the mizenmast standing.

The Mary B. Mitchell was in a bad way, but by no means finished. They close-reefed her mizen, she lay-to, a jury-mast was rigged on the foremast’s stump and a reefed staysail set. There was still a strong gale, but the wind had changed to north-east.

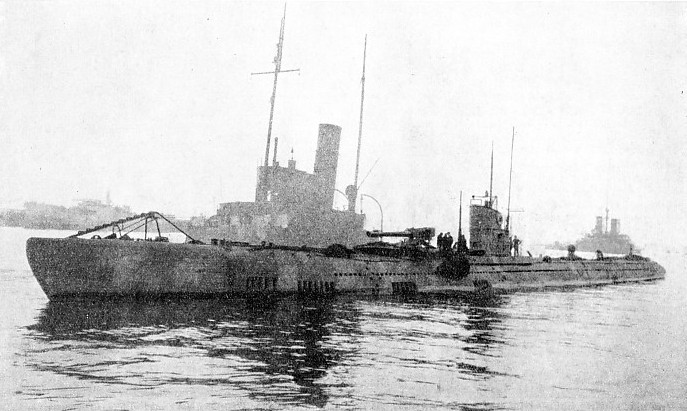

MOTOR LAUNCH 161, under the command of Lieut. Hannah, R.N.V.R., towed the Prize into Kinsale Harbour, Co. Cork, on May 2, 1917, after she had drifted for two days with her engines put out of action by the submarine U 93. This photograph shows ML 161 on her trials at Halifax, Nova Scotia, where she was built. Her decks are covered with snow.

Under this rig the schooner ran towards the south-west, a course that would bring her eventually to the dangerous vicinity of Ushant, with its tricky currents, worse seas and treacherous rocks. She was in no fit condition for dodging about that island or being carried past into the Bay of Biscay. Another anxious night passed, but about 9.15 a.m. on January 9 she sighted a large cargo steamer and signalled her for assistance. For some while the steamer tried to take the sailing ship in tow, but the efforts failed.

Alone once more, a sad speck in that waste of wind-swept waters, the Mary B. Mitchell continued to run before the north-east gale. With Ushant only ten miles off to the southward the weather showed no signs of easing, and the schooner’s situation looked desperate. Distress rockets and a gun were fired every few minutes, flares were burnt; but no help came out from the coast, nor could it be expected. Nearer and nearer the stricken vessel sped through the darkness as to her doom.

There now occurred one of those miracles of the sea which belong to real life and would not be credited in fiction. The schooner did not founder and did not hit a rock; but she discovered a friend. At 9.30 p.m., twelve hours after she had signalled the large cargo steamer, the Mary B. Mitchell spoke the Norwegian ship Sardinia. This steamer stood by till 7 a.m. on January 10 and then tried getting her in tow.

The Sardinia lowered into the seas a buoy attached to a line, to which in turn was bent a thick tow-rope. Lawrie succeeded in picking up the line and hauling the rope on board; the steamer went slowly ahead, and carefully took the schooner from a position ten miles west of Creach Point, Ushant.

Towed Into Brest

Apart from any other considerations, this was a business affair. It was a true salvage job that legally entitled captain, crew and owners of the Sardinia to a handsome monetary reward. The schooner’s name would have to be given, and how could her double character be concealed from the foreigner? Particulars of the ship would be demanded, and must be supplied; yet the surrender of a Q-ship secret might endanger other secret-service vessels.

Lawrie was again aided by coincidence. The towing had proceeded until 11.15 a.m., and they were near Les Pierres Light, when a French torpedo-boat out of Brest approached; so the schooner hoisted her Red Ensign for anyone to see. The next difficulty was how to inform the Frenchman, without the Norwegian’s knowledge, that the dismasted coaster belonged to His Majesty’s Naval Service. With admirable tact, Lawrie now displayed his White Ensign over the stern, yet so carefully that it was hidden from the Norwegians. The French captain’s alert imagination at once perceived the inner meaning. He acted promptly and signalled the Sardinia to cast off. The torpedo-boat then carried on with the tow.

When asked the name of his ship, Lawrie answered: “the Mary B. Mitchell of Beaumaris. Bound from Falmouth to the Bristol Channel with general cargo”.

The information sufficed. Admiralty lawyers could do the rest at a suitable date. No secret had been forfeited. The torpedo-boat brought the schooner safe into Brest, where she was given new masts and fitted out afresh. After an auxiliary motor had been installed, she distinguished herself against submarines. Lieut. John Lawrie won not only a D.S.C. but also a D.S.O.

The finest of all these schooner stories must now be told. Two exceedingly able rival commanding officers and two most efficient vessels contended with each other towards an amazing finale. Never were duellists more evenly matched, nor did a true-life story ever take a more surprising twist.

THE BRIGANTINE DECOY-SHIP Q 17 was the Helgoland, 310 tons, built in Holland in 1895. She was armed with four 12-pounders and a Maxim gun. Her name was changed at one time to Horley. Stationed at Milford Haven, Pembrokeshire, she was renamed Brig 10 later at Gibraltar. She was 122 ft. 9 in. long, with a beam of 23 ft. 3 in. and a draught of 8 feet aft.

In the month of July 1914, I was sailing my yacht from the Solent to Falmouth and stayed two or three nights in Weymouth. In Weymouth Bay were anchored most of that immense mass of warships which shortly afterwards were to be known as the Grand Fleet.

A few days later I entered Falmouth and let go anchor. It was the end of one era and the beginning of another. For suddenly the country was at war, and several strange incidents made this singularly clear. First of all arrived two big Hamburg-Amerika liners up the Fal, thinking that they would find safety and that Great Britain would keep out of hostilities. They were sadly disillusioned, for next week their officers were interned. When these great steamers finally departed it was with the White Ensign flying over the German flag.

All yachting had come to a stop, and we were forbidden to leave port. Scarcely had the declaration of war been made than we saw anchored next to us a typical foreign-built schooner with three masts and a rather high poop. She was of the kind often to be found in Dutch and German waters. The name on her stern showed that she was the Else, belonging to the German port of Leer (near the mouth of the River Ems), but she had been built in Holland of iron and steel. She was of 199 tons, measuring

112 ft. 6 in. long. The Royal Navy had just captured her at the western end of the English Channel, and brought her in as the first prize made during the war.

During August all pleasure yachts began to lay up, and their owners began to command naval patrol craft. Changes took place everywhere. We found ourselves being sent north, south, east and west. I went to serve in an area off the Irish Coast which became the principal zone for U-boat operations as well as for Q-ships. Meanwhile, the schooner Else had been sold to the Marine Navigation Company, which changed her name most fittingly to First Prize.

Epic Encounter

In November 1916 the Admiralty took the Else over and fitted her out after the manner of the Helgoland and the Mary B. Mitchell. She was given two concealed 12-pounders and changed her name to Prize. As captain the Admiralty appointed Lieut. W. E. Sanders, R.N.R., who as a sub-lieutenant had obtained valuable experience on board the Helgoland.

On April 26, 1917, the Prize set out from Milford (Pembrokeshire) for the south-west of Ireland, and on the evening of April 30 had reached lat. 49° 44' N., long. 11° 42' W. On Friday, April 13 — a date which superstitious critics will not fail to note — the new and powerful submarine U 93 had left Emden for the same locality. She measured over 200 feet long, carried one 4·1-in. gun, one 22-pounder, 500 rounds of ammunition and ten torpedoes, and could travel at over 15 knots on the surface. Her personnel comprised thirty-seven officers and men, the captain being Lieut.-Commander Count Spiegel von und zu Peckelsheim, who had previously commanded U 32. This nobleman was a brave if ruthless officer. This maiden cruise had been most successful: U 93 had sunk eleven merchantmen by April 30, and had taken five prisoners. Spiegel was now about to leave the Irish station — where other U-boats were operating — and to begin the return voyage, hoping to be back in Berlin by the second week in May when two of his horses were running in the races.

ONE OF THE LARGE U-BOATS, the German U 120 is seen in this photograph at Gibraltar on her way to be handed over to Italy after the war of 1914-18. Another submarine of this type was U 93, disabled by the Prize in 1917. U 93 was more than 200 feet long and carried one 4.1-in. gun, one 22-pounder and ten torpedoes. Her surface speed was over 15 knots. The crippled U 93 safely reached Germany.

On the morning of April 30 Spiegel saw U 21 sinking a Swedish sailing vessel, so that when U 93, at 8.45 that same evening, sighted the topsail schooner Prize heading to the northwest, doing not more than 2 knots with a light N.N.E. breeze, this seemed to be a gift from heaven. Visibility remained excellent, and for once the Atlantic was calm. Spiegel altered course towards the stranger, whose destruction need not waste much time; everyone who could be spared from below was invited on deck to watch how quickly a schooner could be destroyed.

Spiegel opened fire at range of three miles. Sanders luffed the Prize into the wind, launched his boat, and sent the “panic party” to row about. They consisted of Trawler Skipper Brewer and six men, who conveyed the impression that the coaster had now been abandoned. Sanders and Skipper Meade, however, were hidden amidships within the steel companion-cover, and the remaining crew were concealed by the bulwarks. One gun was placed forward under a false, collapsible deckhouse in charge of Lieut. W. D. Beaton, R.N.R.; the second gun was on a disappearing mounting below the hatchway covers of the after hold. It was strange fortune that an ex-German ship should be attacked by a German submarine.

Spiegel’s two guns were on to their target. He came closer; two shells penetrated the schooner’s hull and burst inside, thus putting the Prize’s motor out of action, wounding the mechanic, destroying the wireless room and wounding the operator. So fierce was the attack that cabins and mess-room were wrecked and the ship began to leak.

Spiegel was gaining confidence every minute, but he wished to make absolutely certain. He therefore approached nearer still, but from dead astern where (he knew) no schooner’s gun could bear. He fouled and carried away, by this manoeuvre, the Prize's log-line. A few minutes later, Spiegel being fully convinced after scrutiny that the Prize was just another old coaster, U 93 sheered on the port quarter seventy yards distant. That was his mistake. Through a steel slit Sanders recognized a golden opportunity. “Down screens! Up White Ensign! Open fire!” Twenty long anxious minutes had ended. It was a fight to a finish now.

Spiegel realized his error of judgment and fired two more shots, wounding one of the schooner’s men. The German captain then tried to ram the Prize, found he was outside the turning circle, altered helm and tried to escape; but to Sanders there remained just one simple duty — to keep on firing till the enemy sank. One shell now struck the submarine’s 4·1-in. gun, blowing it and the gun’s crew to pieces, a second shot apparently ruining the conning-tower. Others followed in torrents of explosions. The submarine was glowing with fire within, and at 9.9 p.m., after thirty-six rounds had been showered on her, U 93 sank below the swell, stern first. Unfortunately the becalmed schooner, bereft of her motor, could not reach the spot and drop depth charges; but the “panic party” rowed over and picked up three survivors. These were Count Spiegel, the navigating warrant officer and a stoker petty officer. Covered by Skipper Brewer’s pistol, the prisoners were taken on board the sinking Prize. It is difficult to imagine a more sudden reversal of circumstances.

Spiegel was not merely a sportsman, but a gentleman. He gave his word of honour not to escape, and lent his men to help Sanders keep the ship afloat. The navigating warrant officer dressed the wounds of the Prize’s injured men, and the stoker petty officer helped the schooner’s mechanics to start the engine. At last through the darkness this listing Q-ship made progress towards Ireland.

Nearly two more anxious days were spent, and everybody expected that one of the other submarines would come along to finish the job. But on May 2, the Prize was taken in tow by Lieut. Hannah, R.N.V.R., In H.M. Motor Launch 161, off the Old Head of Kinsale, and brought into Kinsale Harbour (Co. Cork). Thence a drifter towed the schooner, with her prisoners, to Milford.

S piegel had no doubt that U 93 had been lost. But, she got back to Germany under Sub-Lieut. Ziegler — a most gallant performance. Badly holed on the starboard side, unable to dive, she escaped in the darkness. She gave all shipping a wide berth, and voyaged round the north of Scotland.

piegel had no doubt that U 93 had been lost. But, she got back to Germany under Sub-Lieut. Ziegler — a most gallant performance. Badly holed on the starboard side, unable to dive, she escaped in the darkness. She gave all shipping a wide berth, and voyaged round the north of Scotland.

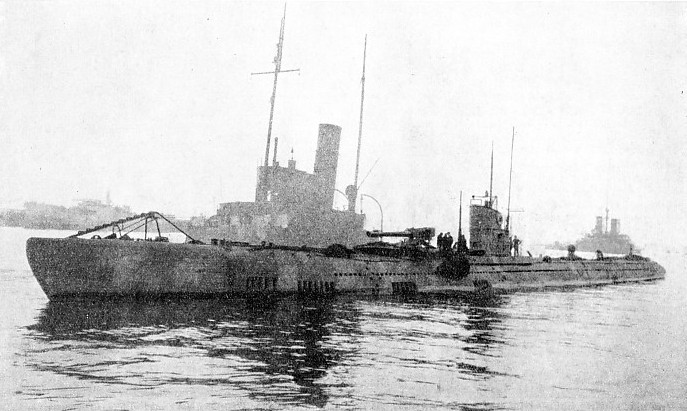

THE BOW AND FIGUREHEAD of the schooner Sidney, built in 1897. She became the auxiliary decoy ship Glen during the war of 1914-18. She was armed with one 12-pounder and one 3-pounder and succeeded in sinking the German submarine UB 39 on May 17, 1917. This was at the peak of the submarine activity and the Glen met two more submarines on the same day.

The Prize’s tragic end shows how dangerously the decoy sailing ships lived. On August 15, 1917, disguised as a Swede, she sailed out into the Atlantic from the north of Ireland, and just after 4 p.m. encountered UB 48. The submarine torpedoed and sank her at 1.30 a.m the next day.

You can read more on “The Convoy System”, “Epics of the Submarines” and

“Troopships & Trooping” on this website.

piegel had no doubt that U 93 had been lost. But, she got back to Germany under Sub-

piegel had no doubt that U 93 had been lost. But, she got back to Germany under Sub-