© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Thames Sailing Barges

The strongly-

ON IN THE RIVER MEDWAY, at Rochester, a number of sailing barges may often be seen lying at their berths. The barge in the foreground of this photograph has a standing gaff on which the upper edge of the sail is extended. All the other barges have sprits, and their sails are brailed up to a point just under the masthead.

ONE of the most remarkable and picturesque of the world’s types of sailing craft is the spritsail barge, still to be found in large numbers on the Rivers Thames and Medway. The type is occasionally seen, also, in a few other counties of England, although it has never really taken deep root far away from the Thames Estuary.

The term “Thames Barge” includes the lighters that are towed or carried by the tide up and down the Thames. The lighters, being merely enlarged punts without power, are strictly utilitarian. The sailing barge, however, is worthy of more attention than she receives. She certainly does not deserve to be looked down upon, as so often happens with folk who think no farther than the name, and the men who take her to sea are certainly seamen in the finest sense. So rapidly has sail disappeared in Great Britain that the bargeman may soon be able to claim himself as the only sailor of the old school. Many authorities claim that all fore-

and-

This spritsail rig was certainly popular on the London River in the fifteenth century, and the general principles of the hull are older still, although the particular rig and the particular hull were not combined until the middle of the seventeenth century. It has to be admitted, however, that there is a strong Dutch influence in some of the features of the barge as she exists to-

There is nothing pretentious about the Thames barge. She is just a plain workaday ship excellently adapted to her purpose and a fine sea-

Undoubtedly one of the great advantages of the Thames barge is the handiness of the spritsail already mentioned, which can be handled by one man. Another is that, with her mainsail brailed up, she will handle remarkably well under topsail alone, or under topsail and fore-

It is not easy to trace the evolution of the barge’s design. Artists rarely painted them except as a detail in a picture of another subject. The barges have, however, been made the subject of a special study by a number of experts who have contrived a connected though somewhat patchy history.

In early times the barges on river and coast can have had but little claim to beauty. As the coaster developed, the evolution of the barge proceeded, more slowly. For centuries the Thames barges had the more normal gaff-

Stumpie-

Until early in the nineteenth century all the spritsail barges were cutter-

It is known that there were numbers of barges with mizen masts in 1820, the invariable custom being to step the mast on the head of the rudder -

In the ’eighties the wheel was introduced into London barges instead of tiller steering; this change permitted the mizen mast to be brought into its present position.

The ordinary Thames barge still has a small mizen, although generally larger than it was when the mast was stepped on the rudder-

ALONGSIDE A WHARF these two sailing barges are waiting to discharge their cargoes. At low water they will be high and dry, but their flat-

Until the early part of the nineteenth century all barges were “stumpie” rigged, that is, they had no topmast or topsail. There are still numbers of them on the Thames and Medway. These surviving “stumpies” are, however, mostly for river work only and for special purposes. The regulations, for instance, strictly limit the amount of gunpowder or other explosive to be loaded into a single barge. For work of that sort a “stumpie” is all that is necessary. In some of the innumerable creeks into which the barges penetrate only a few tons of cargo are offered and a big barge would be wasted on this duty. But the “stumpies” are in the minority. Although many people can remember the days when most barges were without topmasts, nowadays at least nine out of ten are fitted with them, for not only do they permit greater speed on passage, but they also enable the vessels to come alongside under topsail only.

The headsails have developed on much the same lines. Originally the forestaysail was the only one considered for a barge. Even to-

The main sheet is always arranged in the same way, traversing on a heavy wooden “horse” fixed across the deck as it has done since the early days of the eighteenth century at least, and possibly much longer. This is a remarkably efficient arrangement for a vessel with such a small crew, and it is doubtful whether anything else would be as good. That is probably why nobody has been bold enough to suggest an alteration.

The main sheet is always arranged in the same way, traversing on a heavy wooden “horse” fixed across the deck as it has done since the early days of the eighteenth century at least, and possibly much longer. This is a remarkably efficient arrangement for a vessel with such a small crew, and it is doubtful whether anything else would be as good. That is probably why nobody has been bold enough to suggest an alteration.

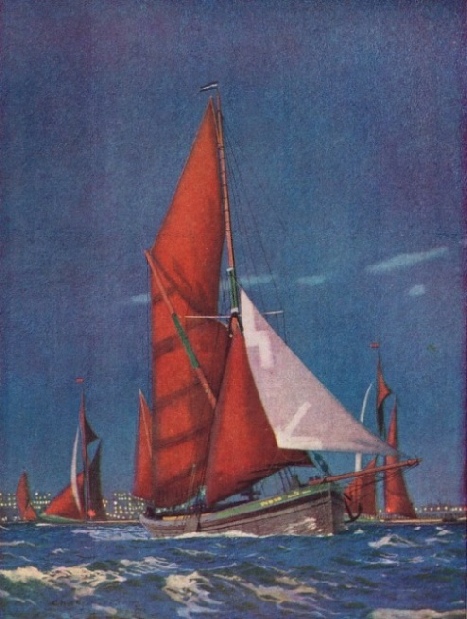

SPRITSAIL BARGES on the River Thames at dusk, from the oil-

The mainsail is almost invariably of precisely the same cut and proportions, a fact which gives the barge her distinctive appearance. Most artists have failed to catch this appearance exactly, the conspicuous exception being the late Mr. W. L. Wyllie, whose etchings of barges delight even the bargemen themselves -

Two Types of Hull

In the earliest days the hull of the barge seems to have been of two patterns, one a square box with a bow and stern rounded and the other an enlarged punt. The second pattern is still practically universal for dumb barges or lighters, without sails. The punt principle developed into the swim-

Another conspicuous feature about the hull is the fitting of lee-

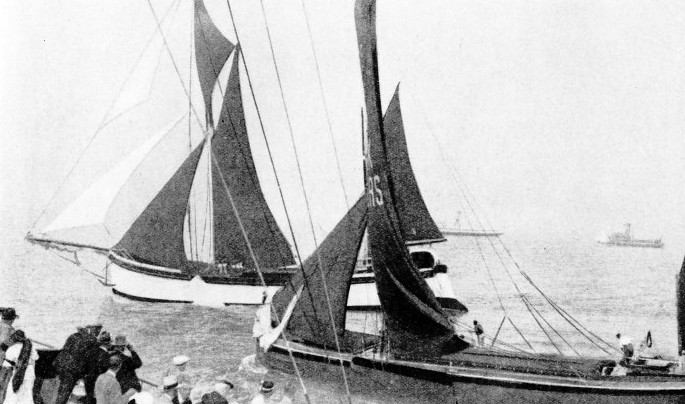

ROUNDING THE COMMITTEE BOAT in the annual Thames sailing barge race. An excursion steamer acts as the Committee boat and marks the turning-

These barges are always well built and some are designed to carry 120 tons with a freeboard of 6 inches. The barge skipper exaggerates a little when he claims that his boat is not really loaded until a robin can drink from her deck. Such a vessel may be 80 feet long by 18 feet beam by 6 feet depth of hold.

A boat of this type, built with the utmost care, is expensive, and it is customary to defer the last instalment of her payment until she has been two months on service and has proved herself capable. In the days that immediately preceded the war of 1914-

As is only to be expected, the accommodation is not elaborate although it is not by any means uncomfortable for the two men who generally make up the crew. In the old open-

The sails of the Thames barge, call for as much notice as her hull and are of just as good quality, at the beginning of her career at least. Tradition says that in the old days sails were of any number of colours, but now they are invariably tanned a rich, warm red with the lighter sails white. With the huge mainsail and big topsail the sail area is surprisingly large, 4,800 square feet in a barge of about 80 tons register.

THE GRACEFUL LINES of the sailing barge Cambria, owned by F. T. Everard and Sons, of Greenhithe, are shown to full advantage in this photograph, taken during the Thames sailing barge race in June 1932. The hull of the Cambria is flat-

These barges were formerly built and equipped in various yards, mostly specialists, on the Thames and in the Home Counties, but the number of these establishments has been steadily decreasing for years and occasionally a contract has gone farther afield. In 1902 Goldsmith, of Grays, one of the best-

There are still on service some exceptionally old barges, a few of them a century old and more -

The Thames bargeman -

SOON AFTER THE START of a Thames sailing barge race. The barges cross the starting line together. Of the four competing classes the coasting class is for barges with a minimum of 70 tons register. There is a separate class for river barges with bowsprits and another for river barges carrying staysails only. The fourth class is for barges of the types illustrated above, but with special conditions applying. The race starts from a point below Gravesend on the Thames.

A word must be said in justice to the Thames bargeman apart from his attributes as a seaman, for in popular fancy he is known principally by his reputation for foul language. This is an absolute injustice. His language is no worse than that of any other man who gets his living on the water -

The trades covered by the spritsail barges are legion, although unfortunately they are declining in face of road competition and full-

The barges still carry coke piled high above their hatches to France, Belgium and Holland all through the winter, although it seems a big risk. Scores of them are employed carrying paper and beer between the Medway and the Thames. Cement and timber give employment to any number. In the old days the hay barges were as numerous as any other type. They were popularly known as “stackies”, and staggered under a 12-

There are plenty of unusual trades in which Thames barges have engaged from time to time. Two went out to South America rather more than twenty years ago. Their heavy sprits were lowered on deck and they went out temporarily rigged as ketches with crews of Ramsgate fishermen. They made excellent time. Many Thames barges have been converted into comfortable yachts and houseboats. Reference must be made to the annual races, one on the Thames and the other on the Medway. In the early ’sixties Mr. Dodd, known as “The Golden Dustman”, organized a proper race which soon became the great event on the river. For a time it was allowed to lapse, but it was revived in 1927 and is now as popular as ever.

Nowadays the race is sailed in three or four classes, without handicap. First, there is the coasting class with a minimum of 70 tons register; secondly, the class for river barges carrying bowsprits; and thirdly, the class for river barges having staysails only. The fourth race is for one or other of these types, with special conditions arranged to ensure a more equitable distribution of the prizes. The Thames course is from a point below Gravesend, round the excursion steamer chartered as Committee boat, and anchored as near to the Mouse Lightship (in the Thames estuary) as wind and other circumstances permit, and back to Gravesend. The Medway course is similar but based on Chatham. The rules demand swept holds, working canvas and purely bargemen crews. The spectator can see sailing that is as fine as any to be seen anywhere.

There are cups for the owners, cash prizes for the masters and crews of the winning boats, and a small sum for the hands of all barges that complete the course. In addition there are numerous special prizes.

There are cups for the owners, cash prizes for the masters and crews of the winning boats, and a small sum for the hands of all barges that complete the course. In addition there are numerous special prizes.

WITH THE WIND RIGHT AFT, the Veronica travels at a fine speed and runs “with a big bone teeth”. Built in 1906, this barge has a registered tonnage of 54.

The more modern iron and steel barges cannot possibly live as long as the wooden veterans, and it is unfortunately true that new construction has for a time been completely suspended in favour of the full-

You can read more on “The America’s Cup”, “Great Voyages in Little Ships” and

“Romantic Sailing Coasters” on this website.