© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Captain Slocum the Pioneer

During recent years a number of daring single-

GREAT VOYAGES IN LITTLE SHIPS -

THE spread of ocean cruising in little ships dates from the end of the war of 1914-

Slocum was born in Nova Scotia, a part of the world from which came hardy adventurers who crossed the Atlantic in dories -

In 1867 two fishermen crossed from Gloucester (Mass.) to Southampton in a dory. Their trip is assumed to be the first, but it may be that there were earlier ones. A fisherman, Alfred Johnson, from the same town, Gloucester, sailed a 16-

After this Andrews made various crossings single-

All these passages were from west to east in the region of the westerlies. Passing ships came alongside and offered the voyagers food and water, and sometimes the voyagers went aboard a vessel to stretch their legs and get relief from their cramped positions before returning to their tiny boats. All stores were invariably lashed in position, as sometimes the boats capsized, and

the lone mariner had to right the boat as best he could and climb in again.

It is much easier to sail from North America to Europe than in the opposite direction, as a small boat has to go south to get into the area of the northeast trade wind which will take her to the West Indies. After this she must turn north again to reach New York. A considerably shorter route is by way of Iceland and Greenland. This route is called the Viking route because it was the route the Viking ships took to Iceland, Greenland and North America about a thousand years ago. The hazards are so great that most srnall-

The Viking route is the graveyard of several stout little ships. A famous American yachtsman, William Washburn Nutting, sailed with three companions in his 42-

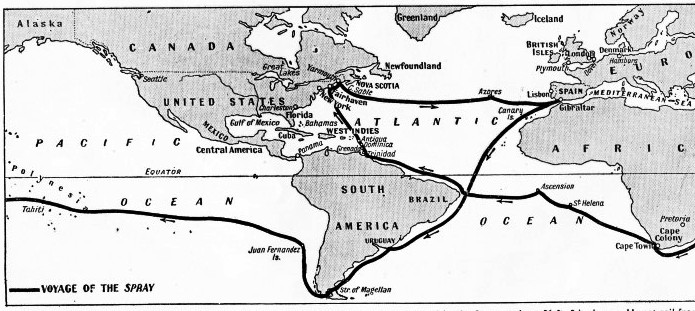

THE CIRCUMNAVIGATION OF THE WORLD by Captain Joshua Slocum single-

Captain Joshua Slocum, however, was the first man to circumnavigate the world single-

Slocum became an American citizen. His Spray thus made her voyage under the Stars and Stripes. He came of seafaring stock, and rose from seaman to master mariner, having been captain and part-

A friend offered Slocum an old sloop -

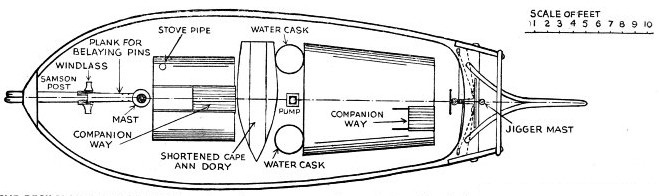

Having set to work with axe and adze, he stripped the Spray of her rotten wood and built what was virtually a new vessel, except that the sound parts of the old sloop were not wasted. She measured 36 ft. 9 in. overall length, 14 ft. 2 in. beam and 4 ft. 2 in. depth in the hold. Her net tonnage was 9 and her gross tonnage 12·71. She cost under £111 for materials, and took Slocum thirteen months to rebuild, although he stayed considerably longer than that at Fairhaven, as he secured occasional work fitting out whalers.

His fishing venture proved a failure. He was confident of his handiwork and, convinced that he could sail his vessel single-

The great beam and shallow draught are two features of interest. Still more interesting is the fact that Slocum obtained such a balance between sails and hull that the Spray needed no helmsman. Slocum lashed the wheel and she kept on her course. It was this fact that mystified many people, including men with considerable experience of the sea.

This balance, of inestimable advantage to any ocean-

Tin Clock as Chronometer

To prepare for the Atlantic crossing Slocum put in at Gloucester (Mass.), where the fishermen gave him dried cod, copper paint, a fisherman’s lantern and various articles. Instead of obtaining a dinghy, he cut a castaway dory in halves and boarded up the stern where she had been cut. This dory also served as a washing-

Slocum was a first-

He touched at the Azores. Shortly afterwards he fell ill through eating cheese and plums. He became delirious and lay in agony on the cabin floor while the Spray held her course for Gibraltar. He recovered and threw the remaining plums into the sea. His patent log was of great help, as this, combined with the practical knowledge gained by his years at sea, made him exceptionally accurate in his dead reckoning.

He touched at the Azores. Shortly afterwards he fell ill through eating cheese and plums. He became delirious and lay in agony on the cabin floor while the Spray held her course for Gibraltar. He recovered and threw the remaining plums into the sea. His patent log was of great help, as this, combined with the practical knowledge gained by his years at sea, made him exceptionally accurate in his dead reckoning.

THE BLUFF LIGHTHOUSE and signal station at Durban, South Africa. From this point Slocum and the Spray were first sighted as they approached South Africa after having crossed the Indian Ocean. The signalman sighted the little Spray at a distance of fifteen miles.

When the Spray arrived at Gibraltar Slocum was well treated by the British naval authorities. He was entertained and his boat was refitted, but he was advised to abandon his intention of sailing through the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal, because of the menace of Moorish pirates. Slocum took this advice and headed the Spray across the Atlantic again, this time for South America, but, even so, he narrowly escaped capture by a Moorish pirate felucca. He was saved by his courage and by the soundness of his gear.

The felucca was overhauling the Spray in a strong breeze. Slocum realized that he had too much sail for the weight of wind and he reefed. A great sea caused the felucca to broach-

In common with all blue-

In South America he altered his rig by reducing the mainsail and adding a mizen, converting it into a yawl rig and thus splitting his sail area. A fortnight before Christmas he ran the Spray ashore on the coast of Uruguay and had a narrow escape when laying out an anchor; the half-

The cheerful mariner’s passage through the Strait of Magellan is one of the epics of the sea. He had not only to contend with the head winds and dangers that beset every sailing vessel, but he was also in peril from the natives. He defended himself by his wits, using his rifle and a few carpet-

A gale blew him back, however, although he fought it for days. Only by great efforts was he able to retreat unscathed into the strait, where he was again pestered by the natives. Before turning in he spread the carpet-

At the island of Juan Fernandez Slocum found settlers. First he treated them to dough-

He made a landfall at Nukuhiva, one of the Marquesas Islands and later landed on one of the Samoan Islands. Here he met Mrs. Stevenson, the widow of R. L. Stevenson. He went on to Newcastle, Australia, and sailed south to Sydney and then to Melbourne. His intention was to go south of Australia, but the weather was against him and, after a stay in Tasmania, he returned to Sydney and then set out for South Africa by the route north of Australia.

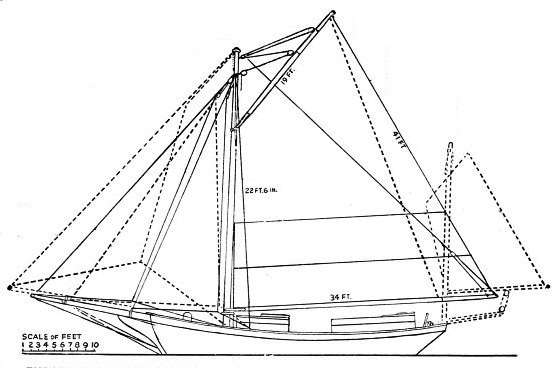

SLOCUM’S FAMOUS SLOOP, the Spray, from a beautiful painting by Maurice Randall. Slocum bought her as a hulk at Fairhaven (Mass.), and rebuilt her. She had an overall length of 36 ft. 9 in., a beam of 14 ft. 2 in. and a depth in the hold of 4 ft. 2 in. It took Slocum thirteen months to rebuild her and the materials cost him £111. Then it took him from April 1895 to June 1898 to sail her single-

This change of plan, with the previous change at Gibraltar, shows that Slocum was a wise man. He had every right to his own opinions, but he frequently took the advice of people of proved experience. Apart from the risk of pirates, which was considerable in those days off the Mediterranean coast of Africa, there was the question of the variable winds, and south of Australia Slocum was faced by the prevailing westerlies. He was always sure of himself, but was never opinionated.

Having left Sydney, the Spray headed north inside the Great Barrier Reef. She put in at one or two places and missed disaster by a few feet. Slocum was popular with the candid Australians. In Tasmania a lady, writing anonymously, sent him some money, but Slocum vowed that he would not make money out of Australians. He gave a lecture at one port and devoted the proceeds to help some miners who had been shipped back from New Guinea broken in health and penniless after a vain search for gold. After having put in at Thursday Island, the Spray sailed to the Cocos-

At St. Helena Slocum was given a goat. As soon as the animal had found its sea-

He then sailed towards Brazil and spoke to an American warship, which signalled that war had broken out between Spain and the United States. The Spray was not stopped by any Spanish vessels. As he approached the West Indies Slocum was worried by the lack of the chart which the goat had eaten. He was alarmed one night by what he took to be the white flash of seas breaking on a reef, and despite all his efforts he could not weather them. At last the Spray was tossed high by the seas and then Slocum was able to see that the flash came from the lighthouse on the island of Trinidad.

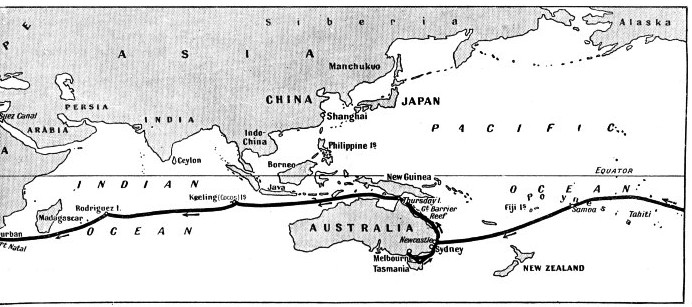

THE DECK-

Slocum tried to buy a chart in Grenada and in Dominica, but there was not one to be had, and he had bitter thoughts of the goat by the time he reached St. John’s, Antigua. From there he sailed for the shores of New England, getting into a sea in the Gulf Stream that proved too much for his worn rigging. He nearly lost his mast when the jibstay broke at the masthead; but he climbed the mast and managed to secure it. He was almost home when a tornado that had caused havoc in New York City struck the Spray, but the alert Slocum had not closed his weather eye. The Spray was under bare poles with everything snug and a sea-

Newport Harbour (Rhode Island) was mined, yet the Spray’s light draught enabled Slocum to sail her out of the mined area close to the rocks and so into the port. He arrived on June 27, 1898, having sailed more than 46,000 miles in three years two months and two days. A little later he sailed the Spray to Fairhaven, and moored her where she had been launched.

No one knows the end of Slocum and his famous Spray. He sailed her alone out of New York Harbour and was seen later by a schooner. The crew of the schooner warned Slocum of an approaching gale. He just waved his hand and was never seen again. It is thought that perhaps the staunch little vessel was run down at night by a steamship. Thus passed a wonderful man and a wonderful boat.

Slocum’s cheerfulness and sense of humour were never dulled by his long, lonely passages and he won the esteem and friendship of everyone with whom he came into contact on his voyage. On his return to the United States his feat was obscured by the excitement due to the outbreak of the Spanish-

Slocum was getting on in years when he sailed, but he was active and agile. He was a superb seaman with an iron nerve. The incident of the chase by the pirate felucca was particularly illustrative, when his seamanship impelled him to shorten sail despite his peril. As long as men sail the oceans in tiny vessels Slocum’s name will never perish.

THE SAIL-

You can read more on “The First Voyage Round the World”, “Great Voyages in Little Ships” and “Supreme Feats of Navigation” on this website.