© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Southampton: Britain’s Premier Passenger Centre

A home for the world’s largest ocean-

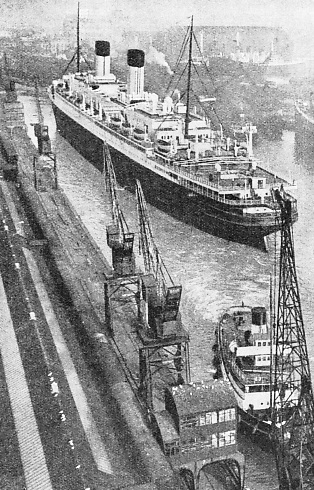

TWO FAMOUS LINERS, the Olympic, in the foreground, and the Empress of Britain in the background, at Southampton docks. Built at Belfast in 1911 by Harland and Wolff, for the former White Star Line, the Olympic had a tonnage of 46,439, a length of 852·5 feet, a breadth of 92·5 feet, and a depth of 59·5 feet. She was sold for breaking up in 1936. The Empress of Britain was built in 1931 by John Brown & Co, Ltd, for the Canadian Pacific Lines. She has a length of 733·3 feet, a breadth of 97·8 feet, a depth of 56 feet and a tonnage of 42,348.

SOUTHAMPTON is the premier port of the British Empire for the great liners. As many as seventeen of the world’s largest liners have sailed from this port in one day. Southampton deals with thirty-

Those five sea miles from the port of Southampton to Calshot Castle are a highway of romance. It is a highway along which men have set out and returned from hazardous enterprises, expeditions of high courage and missions of international importance. In war and peace Southampton and the stretch of water that is a gateway of the world has played its part in history.

Great ships are neither built nor broken up at Southampton. It is their port when they are in the pride of their glory; and it is at Southampton that great ships are helped to keep their glory. Here is the world’s largest graving dock -

Famous firms such as Harland & Wolff, Ltd, and John I. Thornycroft & Co, Ltd, overhaul the ocean giants at Southampton. Liners are dry-

The eastern approach to Southampton Water is through Spithead -

Double tides, a local phenomenon, have added greatly to the value of the port, especially during the war of 1914-

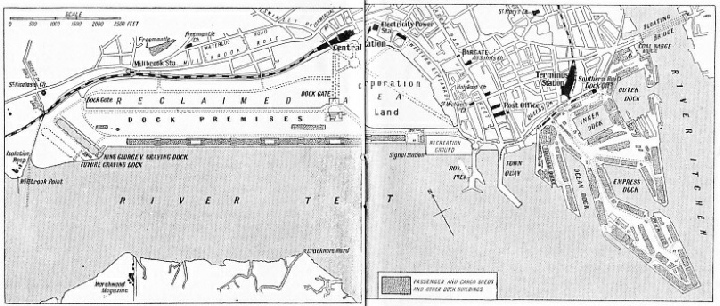

RECENT IMPROVEMENTS AND DEVELOPMENTS of the docks have made Southampton the fourth port in Great Britain for goods traffic. The picture above and the map below show the Docks Extension. In 1927 this was a shallow bay of mud, stretching from the Royal Pier to Millbrook Point. Since 1927 this land has been developed and a 7,000 feet long quay, four passenger and cargo sheds, and the King George V Graving Dock have been built.

Southampton is a port of call for foreign vessels as well as the terminal port of many British liners. The freight traffic has expanded rapidly in recent years, for the railway system connects Southampton with all parts of Britain. In addition there is some transhipment trade; many goods arriving by coastal steamers are transferred to ocean vessels. Improvements and developments of the docks have made Southampton the fourth port in Great Britain for goods traffic. The docks are owned and managed by the Southern Railway, and the harbour is administered by the Southampton Harbour Board, composed of representatives of the Admiralty, the War Office, Trinity House, the Southern Railway and various other interests.

Only seventy-

The channel used by the largest ships is through Spithead. The Needles Channel which leads into the Solent is used by ships up to 20,000 tons. Pilot vessels cruise in the vicinity of the Needles outside the channel, and in bad weather inside the channel. The isolated rocks called the Needles carry a lighthouse and mark the Western corner of the Isle of Wight. On the mainland side of the channel is a dangerous shoal called the Shingles. There is also the North Channel, between this shoal and the Hampshire coast. North Channel, however, is difficult to navigate and not more than 3½ fathoms (21 feet) deep. The run of tides is strong near the Shingles and vessels have grounded there.

The South Channel, as the main channel is called, is about only two cables wide at the entrance, which is guarded by two lighted buoys. The Bridge buoy marks the end of a narrow submerged ridge which extends from the Needles on the starboard side of a vessel entering. The S.W. Shingles buoy guards the edge of the shoal. It is through this narrow gateway that the world’s greatest ships pass out of the western entrance.

Entering from the sea a vessel passes Alum Bay and Totland Bay -

ONLY SEVENTY-

The seaward approach from the east is through Spithead. A vessel coming from the sea passes between Bembridge Point -

Vessels bound for Southampton pass between Ryde and Southsea, towards Cowes. Gosport and Lee-

Calshot Castle is to port as a ship goes up Southampton Water. The deep-

Southampton Water is one of the world’s most interesting and colourful stretches of water. It is used by almost every type of vessel. Paddle-

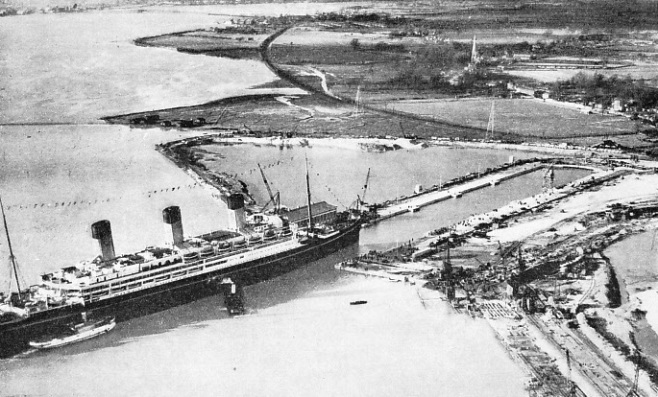

ENTERING THE WORLD’S LARGEST GRAVING DOCK. The 56,000-

The port of Southampton lies at the-

The Outer Dock has a water area of sixteen acres. This dock was the first venture of the Southampton Dock Company and was opened for traffic in 1842. In those days the Outer Dock berthed the largest ocean-

The Greatest Dock

The docks and deep-

The docks and deep-

On one notable occasion the Mauretania (30,696 tons), Berengaria (52,101 tons), Homeric (34,351 tons), Majestic (56,599 tons) and Olympic (46,439 tons) -

A GREAT EVENT IN THE HISTORY OF SOUTHAMPTON. The arrival of the RMS Cunard White Star liner Queen Mary in the King George V Graving Dock after having sailed from the Clyde in March 1936. The three ships to the left of the Queen Mary are the Twickenham Ferry (2,839 tons), the Southern Railway’s car and train ferry, the Cunard White Star Majestic and the Union Castle liner Windsor Castle (18,973 tons), the bows of which can be seen immediately behind the stern of the Majestic.

In addition to these wet docks -

The seventh dock, the King George V Dock, is 1,200 feet overall and 135 feet wide, situated at the western end of the Extension Quay.

The Trafalgar Dry Dock is at the western end of the older dock system. Farther west are the Town Quay, Royal Pier and a recreation ground. Westward to Millbrook Point the Extension Quay extends for nearly a mile and a half, nearly 8,000 feet, and accommodates eight of the largest ships afloat, the minimum depth of water being 40 feet.

The construction of the Extension Quay is one of the greatest engineering feats undertaken in Great Britain. A huge area had to be dredged and reclaimed before the concrete quay could be added. An untidy waste of mud-

The dredgers first scoured a channel two miles long and 600 feet wide, and dredged it to a depth of 35 feet, and of 40 and 45 feet along the quay wall. The soft mud formed a bed between 6 feet and 20 feet deep, and this had to be dredged and dumped out at sea. Under this was a stratum of gravel from 2 feet to 7 feet thick. This was valuable, as it was made into concrete or used to build up banks. The sand and clay underneath were also useful for building up the foreshore.

Below the clay the dredges brought up trunks of trees that once formed part of an oak forest. Bones of deer and the teeth of a wild boar were also found. Laden with the spoil from the dredges, the barges were towed to the site of the new land. First the engineers built up a bank on which to put their gear. Then they enclosed the muddy area, shutting out the tide and leaving a muddy lake to be filled in. The spoil in the barges was saturated with water from pipes, and this mixture was pumped through other pipes until the muddy lake was gradually filled.

Monoliths -

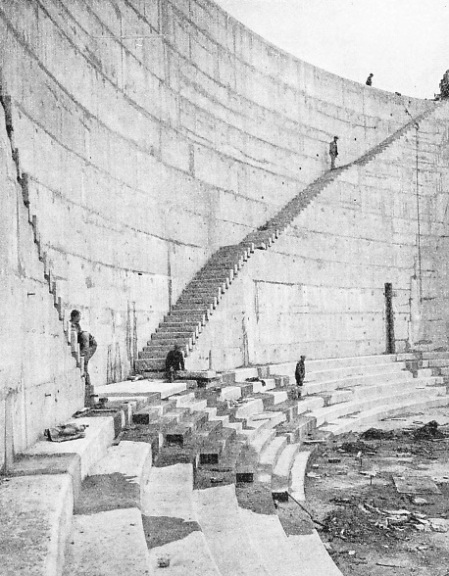

The construction of the graving dock was almost a superhuman task. The engineers surrounded the site with a gravel bank and made this watertight by a curtain of sheet steel driven along the centre line. They pumped out the site and began digging. Water threatened to burst up from below the dock, but tube wells were sunk into the sand and the danger was averted. The dock, which is 59 ft 6-

The largest crane in Southampton is the 150-

THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE KING GEORGE V GRAVING DOCK was carried out in the remarkably short time of under two years, the work having been started in June, 1931, and completed in April, 1933. Some 2,000,000 tons of earth were excavated and about 750,000 tons of concrete were needed for building the walls and floor.

There is a 50-

Fuel oil is supplied by various companies which have storage tanks on Southampton Water, and the oil is taken in barges alongside vessels and pumped from the barges at the rate of 500 tons an hour for each barge One company has supplied liners at the rate of over 1,500 tons an hour by this method. The coal jetty is on the Itchen, but coaling is generally done alongside each vessel. Public interest is centred on the Atlantic liners, and the chief lines are the Cunard White Star, the Compagnie Generale Transatlantique -

Cape Town is 5,987 miles by the Union Castle mail route, and 6,480 by the German East Africa Line’s route. Sydney is 12,137 miles by the Aberdeen and Commonwealth Line’s route. Wellington, New Zealand, is 11,133 miles by the Shaw, Savill and Albion Company’s route. Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires are served from Southampton by the Royal Mail Lines, and by the Hamburg South America Line. Singapore is served by the P. & O. Steam Navigation Co., the East Asiatic Co., the Rotterdam Lloyd and the Nederland Line, and Vancouver by the Royal Mail, Holland American and East Asiastic companies.

These are some of the principal ports served regularly from Southampton, and the list shows the world-

At one period in 1935 eight of the eleven merchant ships in the world with a tonnage in excess of 40,000 tons gross were making Southampton either a terminal port or a port of call. These were the Majestic, Berengaria, Aquitania, Olympic (Cunard White Star), Empress of Britain (Canadian Pacific), Bremen and Europa (Norddeutscher Lloyd) and the Ile de France (Compagnie Generale Transatlantique). The only two other ships were the Rex and the Conte di Savoia of the Italia Line, whose route is to the Mediterranean via Gibraltar.

The Normandie, 86,496 tons gross, made Southampton her first port of call on her westward passage across the Atlantic after she had entered service.

Although the name of Southampton is inevitably associated with the ocean giants, every type of merchant vessel uses the port. The Town Quay is particularly suited to the coasting trade. Ships up to 300 feet in length, with 20 feet draught, can be berthed at the open quay day and night without the assistance of tugs. There are berths for seven or eight large steamers and accommodation is available for numerous small craft.

In addition to the long distance cargo traffic, there is a considerable trade with France and the Channel Islands. The Southern Railway turbine steamers ply between Southampton and the Channel Islands, Havre and St. Malo, and bring passengers, fruit, vegetables and other produce.

The quick transit and cold storage facilities have been utilized to develop the trade in South African and Californian fruit. Apart from citrous fruit, such as oranges, huge quantities of deciduous fruit, such as plums, peaches, apricots, mangoes, grapes and pineapples are unloaded at Southampton. Over 3,500,000 packages of this type of fruit were received in 1934.

The import of French and Spanish wines has been a leading feature of the port since early Norman times. The many old wine cellars at the lower end of the town remain as evidence of the early days of this trade.

A n interesting development was the decision of the Red Star Line to make Southampton a port of call for the Westernland and the Pennland on the New York-

n interesting development was the decision of the Red Star Line to make Southampton a port of call for the Westernland and the Pennland on the New York-

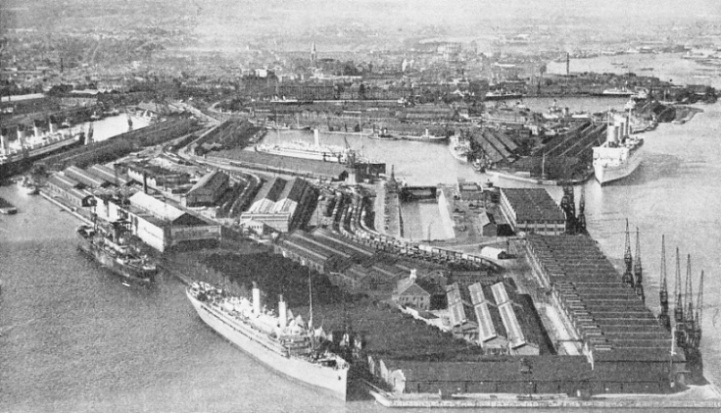

THE WORLD’S LARGEST LINERS use the Ocean Dock at Southampton. On one occasion the Mauretania (30,696 tons), the Berengaria (52,101 tons), the Homeric (34,351 tons), the Majestic (56,599 tons) and the Olympic (46,439 tons) berthed at the same time in the Ocean Dock. This dock, completed in 1911, was first known as the White Star Dock, as it was intended for the big liners of that company. Other great liners also used it, however, and its present name was adopted in 1922. This illustration shows the Homeric being berthed in the Ocean Dock.

Although Southampton was an ancient seaport in the early days of the Christian era, when it was known as Hamptun, it was not until the opening of the Outer Dock, in 1842, that Southampton was in a position to challenge the other ports of Britain. Then the population of Southampton was 28,500. It was obvious that the fortunes of the town of Southampton would grow as the port grew. In 1851, when the Inner Dock was opened, 35,305 people were living in Southampton. This figure had increased to 64,405 when the Empress Dock was opened in 1890.

The greatest increase in the growth and importance of Southampton has occurred since 1892, when the docks system passed from the Southampton Dock Company to the London and South Western Railway Company (now merged in the Southern Railway Company). The London and South Western Railway Company at once increased the accommodation and improved the port’s facilities. In that year the population of Southampton was 65,621. Twenty years later the population had nearly doubled, being then 120,512. In 1933, 179,000 people were living in Southampton.

You can read more on “Great Ports of the World”, “A Great Ship Sails” and

“The World’s Largest Ships” on this website.

You can read more on “The World’s Largest Graving Dock” in Wonders of World Engineering