© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Where the “Queen Mary” was Built

Famous for having built ocean greyhounds and the world’s largest battle cruiser, John Brown’s yard at Clydebank reached the peak of its achievements with the construction of the Cunard White Star R.M.S. “Queen Mary”

LIKE so many other shipbuilding establishments on the Clyde, John Brown & Company began as an engineering shop, for in its early days the River Clyde was even more famous for its marine engines than it was for its ships: a number of hulls built in other centres were installed with engines from the Clyde.

The present firm of John Brown & Co. is a combination of John Brown’s steel interests from Sheffield and J. & G. Thomson’s shipbuilding and engineering works on the Clyde. John Brown’s is the older, having started his steel works in the early part of the nineteenth century. For a long time he was in a small way of business, although recognized as one of the most brilliant men in the industry. In 1854 he laid the foundations of his fortune by acquiring the Queen’s Steelworks, which he renamed the Atlas Works. At that time they were valued at £14,050; fifty years later £2,500,000 was a very conservative valuation. These works permitted him to lead the industry when the world became interested in ironclads through the operations of the first armour-

James and George Thomson started in 1846 as engineers in Glasgow and soon made a reputation for reliable work. They added shipbuilding to their business in 1851, soon after the Cromwellian Navigation Acts had been repealed, when British shipowners were looking for the best and most efficient new tonnage to enable them to overcome free foreign competition. At first Thomson’s went in for comparatively small craft only and had a small yard close to Glasgow.

They had great ambitions, however, and in 1873 moved down to Clydebank. There were then no houses nor railway facilities in the district and many people criticized their temerity in going so far away from all that was considered necessary. But Thomson’s were looking a long way ahead; in their day a 5,000-

ships were going to get bigger and bigger, and they wanted a permanent site. Thomson’s could not, however, have foreseen the extraordinary growth in the size of ships which was to make their yard world-

For nearly ten years after their Clydebank yard was established, Thomson’s kept their engineering side at the foundry at Finnieston, Glasgow; but this meant dividing their operations, and finally they decided to concentrate all their activities in the one yard. The engineering works were, therefore, taken down to Clydebank, where, within a short time the firm had occupied an area of 35 acres. They had eight building slips -

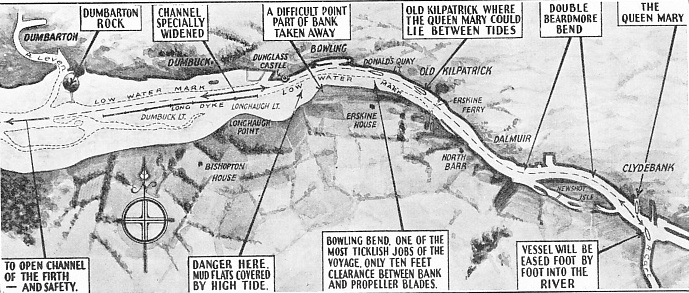

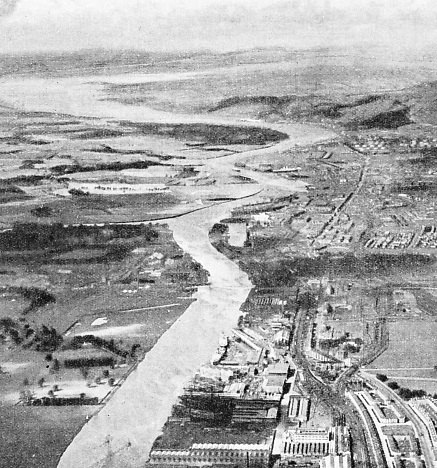

THE ROUTE TO THE SEA taken by all the ships launched from John Brown’s Yard at Clydebank is illustrated by the map above and the photograph below. The map shows the route from the River Cart, and the photograph gives a more general view of the Clyde and of John Brown’s Yard above the Cart, which, in the photograph can be seen, left centre. The map was specially drawn for the sailing of the Queen Mary from the Clyde to Southampton in March 1936, and shows the great skill required to navigate her even after the Clyde had in places been widened. Difficulties faced the pilots from the outset, for it was necessary to ease the Queen Mary foot by foot into the River Cart, opposite the fitting-

By that time they had already built a number of excellent vessels and had been closely associated with the Cunard Company, for which they built such ships as the Bothnia (4,535 tons) of 1874 and Gallia (4,809 tons) of 1879. At that time, however, the Cunard had for some years lost their interest in the Atlantic Blue Riband, and it was on the Cape trade, with the Union Liner Moor, that Thomson’s first came into real prominence for speed. Their first Blue Riband was gained with the National Liner America. She was laid down in 1883, a beautiful clipper-

Thomson’s had done all that they were asked to do; it was not their fault that her owners attempted to run a single ship service and, like other owners who have tried to do that, very nearly ruined themselves over it. She became an Italian cruiser and it is a tribute to her builders that she was in commission as the Italian Royal Yacht after the war of 1914-

The America had shown what Thomson’s could do with this type of vessel, and towards the end of the ‘eighties, when the British Government was willing to support the construction of bigger and faster Atlantic liners to have them as a reserve of cruisers in wartime, the Inman Line went to them for the City of New York and the City of Paris. These were ships of 10,500 tons apiece, designed as rivals to the White Star Teutonic and Majestic, of approximately the same size and speed. The competition between these four ships was intensely keen and took the speed of the Atlantic record to over twenty knots for the first time; but in the early ‘nineties the American shareholders in the Inman Line secured the transfer of the company to America as the American Line, and the City of New York and the City of Paris became the New York and Philadelphia, famous in war and peace. They were not only record breakers but they were also well-

In 1899 John Brown & Co. of Sheffield were looking out for a shipyard to combine with their steel business and chose that of J. & G. Thomson after having examined almost every establishment that was likely to be sold for the very good price that they were willing to offer. John Brown’s were not only pleased with the organization and reputation of the firm, but also they saw the possibilities of indefinite expansion and were looking well ahead on the naval and mercantile sides.

The change of ownership made no difference to the yard’s policy, except that it gave it bigger resources for expansion. The Cunard Saxonia (14,281 tons) of 1900 was designed for the greatest comfort and had a splendid reputation for steadiness. She was followed, among many other ships, by the Cunarders Carmania and Caronia of 1905 -

When the Government decided to assist the Cunard Line in the building of the 25-

John Brown’s had the contract for the Lusitania, and to permit her launch expensive dredging operations were also necessary. The ship was an unqualified success, recapturing the Blue Riband after it had been held by the Germans for ten years, and was a great popular favourite until she was sunk by a torpedo on May 7, 1915.

At almost the same time as they built the Lusitania John Brown’s also built the pioneer battle cruiser Inflexible, and she did so well that they were given the contract for the battle cruiser Tiger shortly before the war. These were in addition to many other men-

Since the war of 1914-

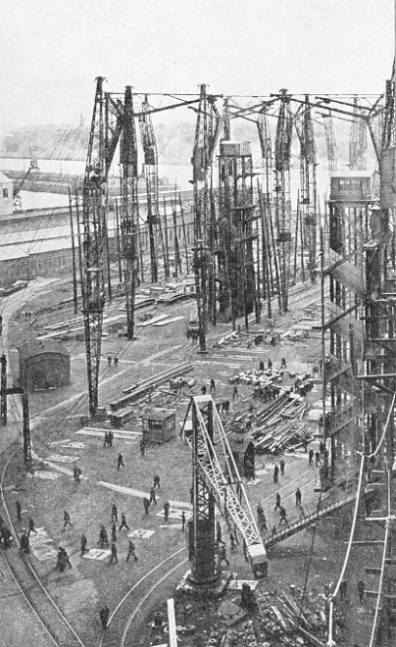

A large part of the success of the yard is due to the great care which has been devoted to the lay-

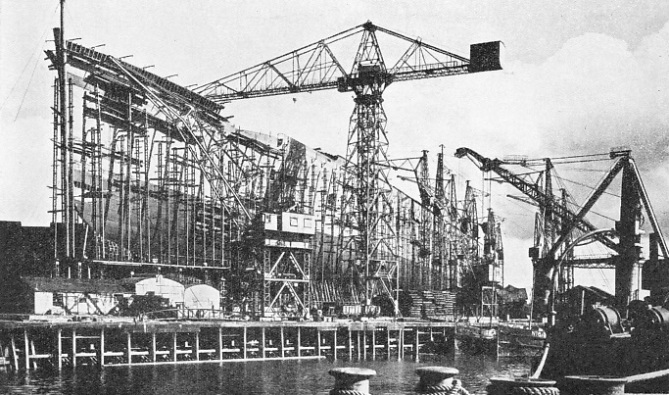

A VIEW OF JOHN BROWN’S YARD taken during the building of the Queen Mary. The ropes in the right foreground and the lift just beyond are alongside the famous Cunard White Star liner. The Yard is situated on the North bank of the Clyde and is divided into two yards, the East and the West, by the fitting-

The advantage of the steady supply in a big contract, especially when it has to be carried out against time, is obvious, but the company also gained immensely by supplying so much of its own material; it has not only proved economical but it also avoids the risk of items being delivered out of their time and so checking the smooth progress of the work. The company not only owns various steel firms, but also has a controlling interest in the Dalton Main Collieries Ltd, with a big coal production; yet so carefully has the yard been built up, and so conservative has been the finance of its owners, that the yard and the engineering works stand in the company’s books at not much more than the purchase price in 1899, although they have been improved out of all recognition, can tackle very much bigger jobs and have an infinitely wider range of activity.

The Yard is situated on the North Bank of the Clyde, and is divided into two yards, the East and the West, by the fitting-

There are eight slips for the construction of ships, the biggest capable of taking a vessel of no fewer than 1,000 feet in length. Five of these are in the East, or Main, Yard, and the three other slips in the West, two of the three being covered in and specially adapted for the rapid construction of particular types such as torpedo-

millions of cubic yards of earth were removed for the purpose. The foundations were reinforced far more than appeared to be really necessary, so that there should be no chance of their failing under the enormous weight that was put on the slip. How wise the company was in going to this expense was shown when the construction of the ship was held up for many months. It was quite generally believed that she had sunk considerably, as she might be expected to do in such circumstances, but she was not distorted by one inch, and this aspect has impressed technicians abroad more, perhaps, than any other. The yard has a frontage on to the River Clyde of over 1,000 yards, situated on the North Bank of the river directly opposite the point at which the tributary Cart runs into it. This offers additional water for the launch of an exceptionally large ship, and when the Queen Mary was to come off the slip, the tributary was dredged considerably to ensure absolute safety.

The building slips, with their elaborate equipment, are backed by numerous shops of all kinds, and the firm is one of the very few private concerns in Great Britain to maintain its own experimental tank. This was installed in 1903, is carefully placed to obtain the maximum results, and has wet and dry docks at either end for trimming the models. The elaborate plant necessary for making the wax models to the required precision is grouped round the docks; the towing carriage and all necessary auxiliaries are electrically driven. This tank is 400 feet long by 20 feet wide, and in it sixteen models of the Queen Mary made over 4,000 trials.

The engineering shops are conveniently placed in a central position on the North side of the works, at the head of the fitting-

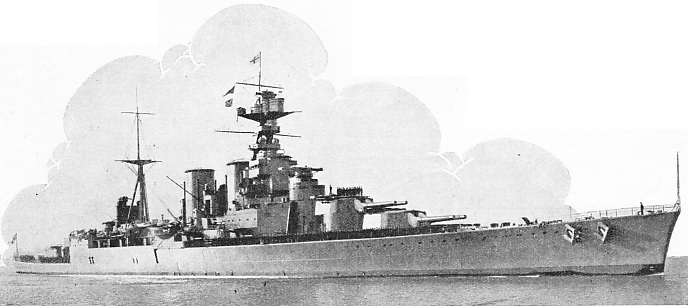

THE WORLD’S LARGEST BATTLE CRUISER, H.M.S. Hood, was built by John Brown & Co, at Clydebank. She was begun on September 1, 1916, launched on August 22, 1918, and completed on March 5, 1920. She has a displacement tonnage of 42,000, an overall length of 860 ft 7-

The photogravure supplement accompanying this article can be seen here.

You can read more on “Glasgow -

You can read more about “Making Giant Propellers” for the Queen Mary in Wonders of World Engineering

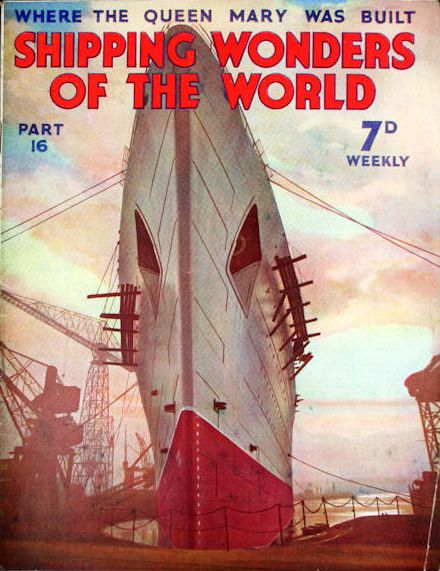

The Queen Mary also featured on the cover of Part 16 of Shipping Wonders of the World, with the following caption:

.