© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Blue Riband of the Atlantic

One of the most coveted honours of the sea, the Blue Riband of the Atlantic has a history that is as dramatic and as interesting as any

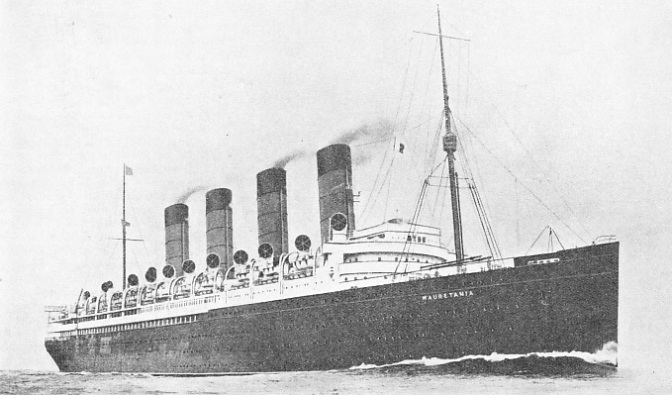

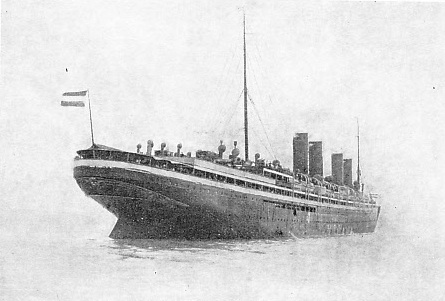

TRIUMPHANT FOR TWENTY YEARS. The Mauretania, built in 1907. In 1909 she logged an eastward record at an average of 25·89 knots and a westward record at 26 knots. Her time from Daunt’s Rock (entrance to Cork Harbour) to Sandy Hook (New York) was four days ten hours forty-

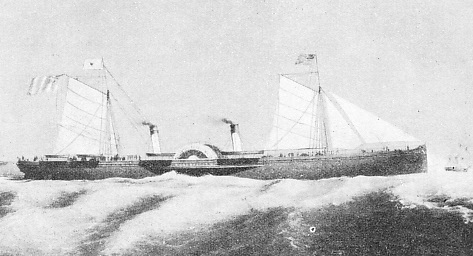

SAILING-

In the early days there was little effort to attain speed on the Western Ocean, the only fast Atlantic ships being the slavers, which did not carry voluntary passengers. Transatlantic trade began on a big scale after Waterloo. Sailing packets were fine ships and

developed rapidly when, after a lapse of time, owners made a real attempt to improve their speed; but the owners took few pains to make their performances known. Steam came in gradually, and the heavy coal consumption of the primitive boilers prevented any great effort to accelerate the service.

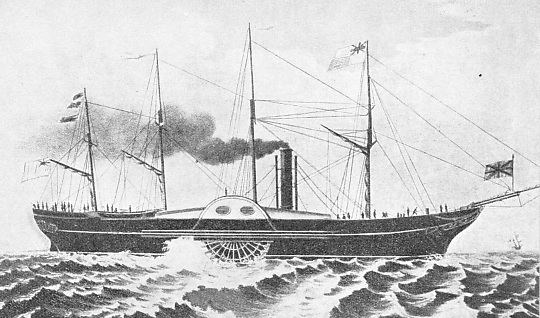

Brunel’s steamer, the Great Western, might be described as the first holder of the Atlantic record, for she undoubtedly beat her rival, the Sirius, to New York in 1838. But the race was more or less accidental, for the steamers started from different points. That they finished at New York on the same day, with the Great Western’s passage from Bristol five days shorter than that of the Sirius from Cork, surprised all concerned. The winner’s average was 8·2 knots, a figure that gives a starting line to the competition.

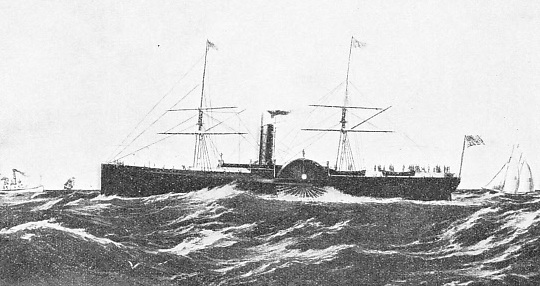

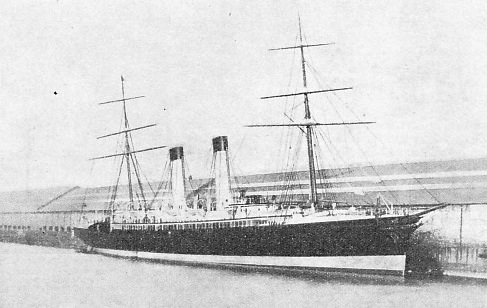

BUILT IN 1849, the Baltic, one of the first fleet of the American Collins Line, which was begun with Government aid to capture some of the transatlantic trade for the USA. The Baltic and her sister ships were bigger than the contemporary Cunarders and were the most luxuriously fitted ships of their day. The Baltic had a length of 282 feet and a beam of 45 feet. Her tonnage was nearly 3,000, and her simple side-

In 1840 the Cunard Company began operations with four sister ships. It was that feature which made their success; individually many of their competitors’ steamers were far better, but they were a mixed collection. Neither the Cunard nor any other owner said much about speed, although the average of the Cunarders was much better than that of the sailing packets. On her maiden passage the pioneer Britannia averaged 8·5 knots between Liverpool and Halifax; but that was scarcely a fair test, because there were doubts about her coal consumption, and her people were naturally anxious to eke out their supplies. Later in the same year she did the eastward run from Halifax to Liverpool at an average of 10·56 knots. The Acadia, the best steamer of the original quartette, logged records of 9·25 knots westward and 10·75 eastward, later improving on the eastward performance by a fraction of a knot. The design of the pioneer class was only slightly improved in the Hibernia type; but the Hibernia herself averaged 11·67 knots eastward and the Asia, a rather bigger ship built in 1850, contrived 12·12 knots westbound, and slightly lowered the eastward record.

In the ‘forties of last century the Americans were enjoying a high reputation for the speed of their sailing ships. When they were in such keen competition with the Cunard Company for the Atlantic business they naturally wanted to make the most of this, and built their packet ships for speed. They were remarkable vessels, but they could not equal the steamers in either sustained speed or general average of passage. In 1847 the Americans made their first serious attempt in transatlantic steam navigation with the subsidized Ocean Steam Navigation Company’s service. It was a daring move, for American shipbuilders and engineers had no experience of building such ships or their machinery. Thus it is not surprising that their design was faulty, their boilers too small to keep the engines in steam, and their paddles too deeply submerged. The result was that they failed to beat the Cunarders’ time, and eleven-

Although the Ocean Company’s steamers were a failure, the Americans were determined to have their share of the trade, and the Collins Line was begun with Government help. Mr. Collins himself had long experience with transatlantic sailing ships and built in 1849 the wooden paddle-

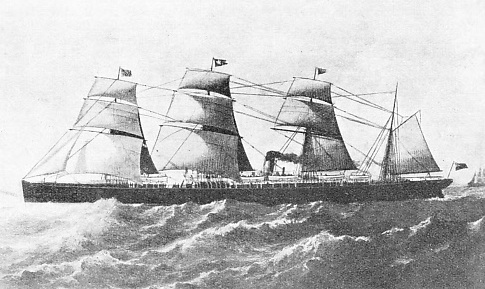

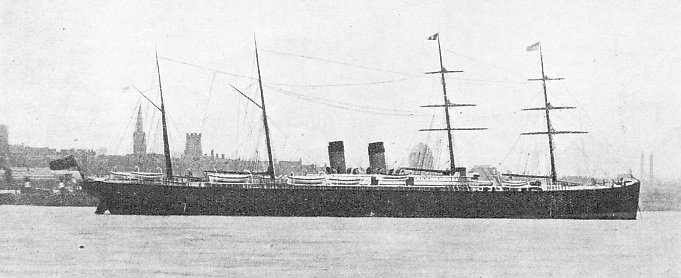

WITH STEAM AND SAIL. The White Star Liner Oceanic of 1871, having a gross tonnage of 3,707, a length of 420 feet and a beam of 41 feet, was longer and narrower than any ships designed for transatlantic service until that date. She was the pioneer ship of the White Star Line and the foundation of its success. Although this ship did not achieve any records, her sister ships did.

The Cunard directors, determined that the company should regain its former position, built some remarkably fine paddle-

These fine ships were built largely because of danger which threatened from another quarter. In the ‘fifties Irish political influence was great, and the scheme to establish a service from Galway in Western Ireland to St. John’s, Newfoundland, and New York received such strong political backing that the Post Office gave the promoters a mail subsidy against the Cunard. Had they been able to do what they promised it would certainly have been a good bargain. Basing their estimates on the achievements of the cross-

For this service they ordered four paddle-

THE FIRST ATLANTIC RECORD was claimed by Brunel’s steamer, the Great Western, which beat her rival the Sirius to New York in 1838, with an average of 8·2 knots, though the race was a fortuitous one. The Great Western had a length of 212 feet, a beam of 35·3 feet, and a tonnage of 1,340. Her paddles were driven by two simple engines working with a steam pressure of 15 lb.

Then the competition of the Inman Line began to develop. William Inman had been steadily improving his steamers and appreciated the publicity value of the Blue Riband just as much as Collins had done. His first success was in 1867 with the City of Paris, making the shortest westerly passage, which was given great publicity in Europe and the United States, although it was really due entirely to the short route selected; the average speed was slightly less than that of Scotia. But in 1869 the City of Brussels undoubtedly beat the Scotia’s best eastward time by half a knot, averaging 14·5 knots. There was great rivalry between the Cunard and the Inman Lines in the ‘sixties, and the latter’s screw ships certainly had the advantage over the Cunard’s paddlers.

In 1867 the Cunard screw vessel Russia secured the eastward record with an average of 14·22 knots, but within a month she had lost it to the City of Brussels with 14·66 knots. In 1870 another competitor appeared in the White Star Line. Its Atlantic liners were built on an entirely new principle, on which Mr. Edward Harland, of Harland and Wolff, the Belfast shipbuilders, staked everything and made his reputation. These ships were very long, arranged internally on a novel principle and, with their single funnel and four masts, introduced a new rig. In 1872 the Adriatic beat the westward record with an average of 14·5 knots, and in the following year Baltic took the eastward average up to 15 knots. The rivalry thus changed to one between the Inman and White Star Companies, the Cunard letting the record go and building inferior ships for a time. This caused a bitter newspaper controversy. Both companies built new tonnage, of which the White Star Germanic and Britannic were the most conspicuous ships. Eastward, the City of Berlin averaged 15·25 knots in 1875, the Germanic contriving 15·75 knots in the following year, only to lose the record to her sister the Britannic with 16 knots in the same year. Westward, the City of Berlin’s 15 knots logged in 1865 was beaten by the Britannic’s 15·25 in 1876 and by the Germanic’s 15·5 in 1877. In the same year the Britannic beat her sister on time alone, not in average speed.

Noticing the success of the Inman Company in breaking into the saloon business, the Guion Line, which also had originally carried on a purely emigrant business, made its first attempt to build record-

THE IRISH CHALLENGE. In the ‘fifties a scheme was broached in Ireland to establish a fast service between Galway in Western Ireland and St. John’s and New York. For this service orders were placed for paddle-

The Montana disabled all ten of her water-

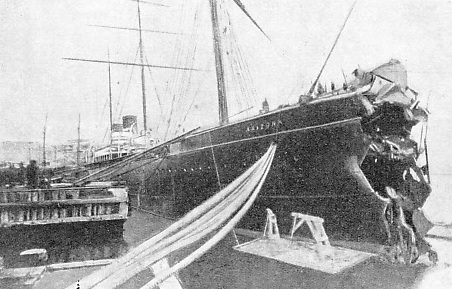

Despite their failure, Mr. S. B. Guion, who controlled the company, persisted in his ambition, but wisely went to one of the best shipbuilders in the country, John Elder & Co, who later became the Fairfield Yard. In 1879 they built him the Arizona, the first ship to be nicknamed the “Atlantic Greyhound” and the first to be propelled by a three-

Made bold by the publicity which the Guion steamers’ records had obtained, a third emigrant company, the National Line, determined to try the same policy and built the America, a particularly beautiful clipper-

A HANDSOME CLIPPER-

During these developments, the Inman Company had not been idle, but in 1881 took delivery of the beautiful City of Rome, specially designed to regain the record. Had the original design been adhered to it is probable that she would have done so, for the substitution of steel for iron in her hull had greatly reduced its weight. But supplies of shipbuilding steel were short, and to obtain delivery the company sanctioned the use of a large proportion of iron.

Thus her hull was much heavier than had been calculated. As she could neither make her designed speed nor carry her guaranteed cargo, she was thrown back on to the hands of her builders, who put her under the management of the Anchor Line. She was a popular passenger ship and her speed improved later, but she was never a record breaker.

In 1884 the Cunard Company had come back into the record class with the sister ships Umbria and Etruria, going to the Fairfield Yard for them as the Guion line had done. The transfer of the Oregon to the Cunard flag robbed these two ships of their principal purpose, but they were remarkably successful and popular. As with the White Star Britannic and Germanic ten years previously, they exchanged both records backwards and forwards between them by fractions of a knot; but finally the Etruria secured both westward and eastward records with an average of 19·5 knots.

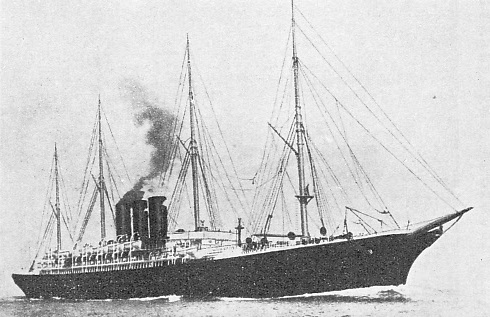

THE FIRST ATLANTIC LINER TO EXCEED 5,000 TONS was the White Star Liner Germanic. In 1876 the vessel covered the eastward passage at an average speed of 15·7 knots. The ship had compound tandem engines of 5,100 ihp. Her sister ship was the Britannic.

It was in the ‘eighties that the possibilities of the Southampton record began to assume shape. Liners between the United States and the Continent had called at Southampton since the ‘forties. But they were of moderate speed, and it was not until the French and German companies, Compagnie Generale Transatlantique, North German Lloyd and Hamburg-

The White Star Company first took full advantage of this subsidy arrangement, which eased the cost considerably, and it made the most of the advertisement afforded by the inspection by the German Emperor of the Teutonic as an auxiliary cruiser. The Inman Line immediately followed suit. The result was the construction of the White Star Teutonic and Majestic, and of the Inman City of Paris and City of New York, in 1888 and 1889. These four ships differed widely in appearance, but were evenly matched in size and speed. Rivalry between the four lasted from 1889 to 1893 and ended in the westward record being held by the City of Paris with an average of 21 knots and the eastward by the City of New York with 20. When the Inman Line failed the remnants of its fleet and business were taken over by the American Line, which transferred the terminus to Southampton with these two ships. They thus drew attention to the Southampton record. This had been lowered by the Hamburg-

IRON INSTEAD OF STEEL in the hull of the City of Rome meant a heavy ship and a failure to break the record. Built in 1881 for the Inman Company, the City of Rome was designed to regain the Blue Riband, but, as supplies of shipbuilding steel were short, the company had to sanction the use of a larger proportion of iron. Her gross tonnage of 8,144 made her the biggest ship of her day except the Great Eastern, and her crank compound engines had an ihp of 11,500.

Then came what was, perhaps, the most dramatic incident in the history of the Atlantic record. The North German Lloyd had been beaten by the Hamburg-

Meanwhile, in 1900 the Hamburg-

A GERMAN SUCCESS. The North German Lloyd Line of pre-

But there was no doubt as to the success of the policy of the directors of the North German Lloyd. In the year after they had won the record their ships carried 25 per cent of the total number of transatlantic passengers. They improved on the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse design with the Kronprinz Wilhelm, which won the westward record with 23·09 knots, but the eastward on time only. The next ship was the Kaiser Wilhelm II which also was successful on time only, and the fourth was the Kronprincessin Cecilie, which had no time to get into her stride before the record had passed into the hands of the Cunard Company again.

The triumph was attained by the Lusitania and Mauretania. These ships were built in 1907, with the assistance of the Government to keep the British flag in a predominant position, despite German success and the immense financial operations of the late Mr. Pierpont Morgan, who had founded the International Mercantile Marine group. The Government lent the company money on easy terms to build the two ships, which were far bigger than any previously considered. It also paid the company an annual subsidy to have them available as auxiliary cruisers, a purpose for which they proved unsuitable when war broke out. The Lusitania was completed first. Nursing her turbine engines, which had never before been fitted into an express steamer, she immediately won the eastward record with an average of 23·61 knots and, having found her form, the westward with 24·25. That was in 1907; two years later she brought her average westward speed up to 25·01. The Mauretania was a little later and took longer to get into her stride, but in 1909 she logged an eastward record at an average of 25·89 and a westward at no less than 26·06 knots. Her time from Daunt’s Rock (entrance to Cork Harbour) to Sandy Hook (New York) was four days ten hours forty-

A LUCKY ACCIDENT. The Guion Company’s first successful record-

The early days of the war proved that the express liner was useless as an auxiliary cruiser because of the difficulty in keeping her in coal, and when matters were readjusted after the Armistice there seemed to be little chance of the owners obtaining Government help on that score. It was also generally believed that the post-

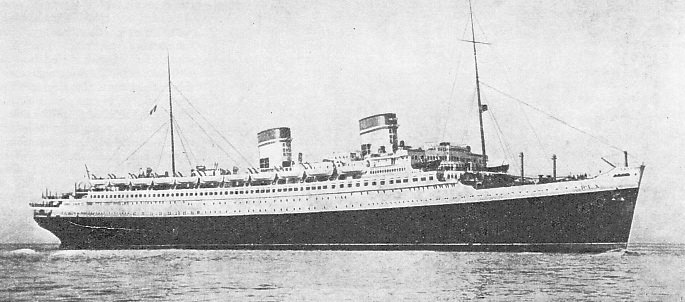

The influx of American tourists to Europe by the northern route did not suit the Italians. With the assistance of the Government, who insisted that competition within the flag should be abolished and that the Italia Line should be formed by a combination of the rival Italian companies on the Atlantic run, they built the Rex and the Conte di Savoia, the first record-

AN ITALIAN RECORD-

The diversion of the American trade to the southern route was as unpalatable to the French as the northern tendency had been to the Italians. State aid was, therefore, readily given to the Compagnie Generate Transatlantique to build the great liner Normandie, described in the chapter beginning on page 73.

She gained the Blue Riband on her maiden voyage by a large margin. From Southampton to New York she made a mean speed of 29·53 knots. The highest speed recorded on this run was 31·37 knots. On the eastbound voyage her mean speed was 30·34 knots, the highest recorded speed being 30·91 knots.

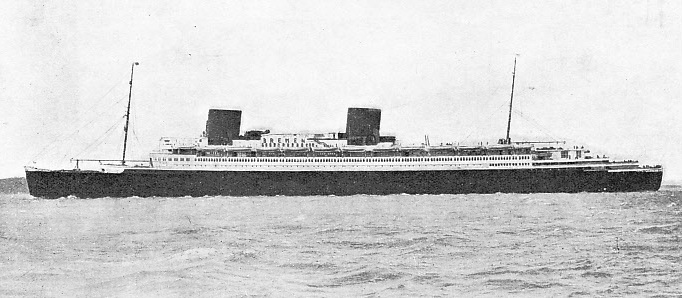

BUILT FOR SPEED. The North German Lloyd liner Bremen averaged 27·9 knots on an eastward voyage across the Atlantic in 1929, and her sister ship, the Europa, averaged 27·91 knots westward, thus regaining the Blue Riband for Germany in that year. The Bremen (above) has a gross tonnage of 51,656 tons, and a passenger capacity of 739 first class, 596 tourist and 830 third. Built in 1929, she has a length of 898 feet and a beam of 101·9 feet. The Europa has a gross tonnage of 49,746.

You can read more on “The Bremen and the Europa”, “RMS Queen Mary” and

“The Triumph of the Normandie” on this website.