© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Famous “Great Eastern”

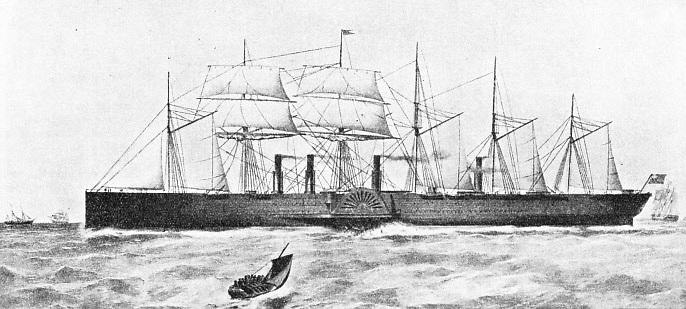

It was not until more than fifty years after the keel of the “Great Eastern” was laid down that vessels of larger dimensions were put into commission. She was a unique ship, provided with sails and paddles as well as with a screw propeller

THE LARGEST SHIP OF HER TIME, the Great Eastern had a gross tonnage of 18,914. She had a length of 692 feet along her upper deck and a beam of 120 feet across her paddle-

LEVIATHAN of the seas for nearly forty years, the Great Eastern was the largest and most wonderful ship of her time. It was not until a decade after the great vessel had been broken up that her dimensions were exceeded. The design of her hull was completely distinct from those of her contemporaries. In many ways the building methods employed resemble those in use at the present day. The Great Eastern has often been described as “born out of her time”.

The idea of building a ship four or five times the size of any other then afloat was conceived in the mind of Isambard Kingdom Brunel about the middle of the nineteenth century. Appropriately enough, the Great Eastern was originally called the Leviathan, and it was Brunel’s suggestion that she should ply between England and either Calcutta or Colombo, where smaller steamers would pick up her cargo and distribute it to its several destinations. Brunei was the creative genius of the Great Western Railway, but he was well acquainted with ships and shipping.

It was Brunel who created the dock and harbour works at Monkwearmouth (Co. Durham), Plymouth (Devon), Briton Ferry (Glamorgan), Brentford (Middlesex) and Milford Haven (Pembroke). He designed the wooden paddle ship Great Western and the iron screw steamer Great Britain. The Great Western crossed the Atlantic in 1838.

The Great Britain left Liverpool on July 26, 1845, and arrived in New York fifteen days later. She was the first screw steamer to cross the Atlantic, and she was in all ways a successful vessel. There can be no doubt that Brunel’s experience with these earlier ships supplied him with valuable data for the design of the Great Eastern.

In 1852 Brunei laid his proposals for a super-

There was, however, one special difficulty that had to be overcome before a large ship could be depended upon when encountering heavy seas. This was the tendency to break her back, either when supported at bow and stern by only two large waves, or when poised amidships on a single wave which left her bow and stern hanging in mid-

The ship was planned in the form of a huge girder, almost rectangular in section, with a double skin and framing that was arranged longitudinally. These longitudinal frames were 2 ft 9½-

The Great Eastern was strongly built, and can be considered not only a bold experiment, but also a triumph for British shipbuilding in the last century. The iron plates of the inner and outer skins were approximately ¾-

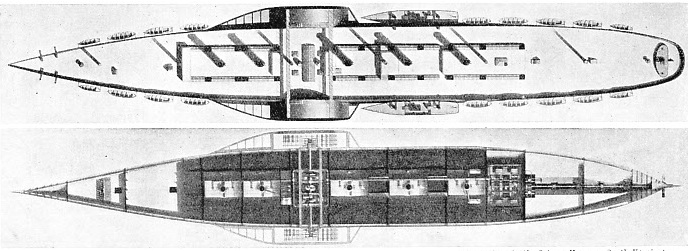

The safety of the ship was increased by extensive subdivision into watertight compartments in addition to the double skin. These were formed by transverse bulkheads at intervals of 60 feet. In the bulkheads there were no openings below the second deck. There were also two longitudinal bulkheads, 36 feet apart, that extended for 350 feet of the ship’s length.

In addition to the main bulkheads there were others at the bow and stern, and in each compartment were intermediate longitudinal bulkheads carried up to the main deck. They formed the coal bunkers. There were two continuous tunnels through the main bulkheads near the water-

The dimensions of the Great Eastern sound imposing even when compared with many modern liners, except for such mammoths as the Normandie and the Queen Mary. The ship displaced 27,384 tons (gross tonnage 18,914), and her length on the upper deck was 692 feet. The length on the load water-

The lines of the Great Eastern followed the form that had been in use for some years. She was built by Mr. Scott Russell, the famous ship designer and head of the firm of John Scott Russell and Co, who built her hull, together with the paddle wheels and their engines. The screw engines were built by James Watt and Co, of Birmingham.

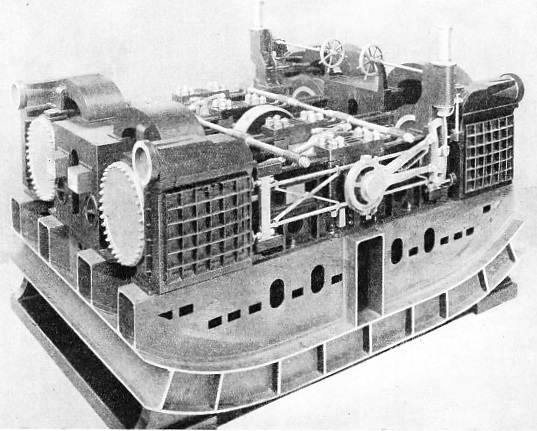

THE DIRECT-

It was customary, even in those days long before the existence of the wonderful ship-

After nearly four years of toil the Great Eastern’s huge iron hull, weighing tons, was ready for her launch. Brunel insisted that the launching should be carried out “broadside-

When the day of the launch arrived, with fitting ceremony the huge vessel was started on her way to the water. Unfortunately, in the anxiety to avoid “overshooting” the river, the progress of the launch was prematurely arrested. The iron cradles stuck on the slipways, also of iron, and the vessel came to a standstill. For three months the ship remained on the launching ways, and not until January 31, 1858, was she safely afloat. The launch was accomplished only by the use of extensive hydraulic machinery, costing thousands of pounds, that pushed the 12,000-

The unexpected and expensive delay in the launching of the Great Eastern led to the liquidation of the company in whose service she was intended to run. She was sold to another concern for service on the northern route across the Atlantic. The ship was unsuited for the Atlantic trade, for she had been intended for voyages to the East. Herein lay one reason for her financial failure in later years. The Great Eastern was not ready for her trial trip until September 1859, five years and five months after the laying of the keel plates.

The strain of controlling this vast enterprise had told heavily on Brunel’s health. On September 5, 1859, the great engineer saw the engine trials of his but when he returned home on that day he was seized with a paralytic stroke. Ten days later he died.

The Great Eastern made her first voyage across the Atlantic in June 1860, at an average speed of nearly 13 knots, with an average coal consumption of 551 tons a day. The technical details of her paddle machinery are given in the chapter “Oscillating Paddle Engines”. The four great cylinders of the paddle engines had a diameter of over 6 feet and a stroke of 14 feet. They must have presented a magnificent spectacle as they swung ponderously backwards and forwards on their trunnions. With a flash of polished cranks and massive big-

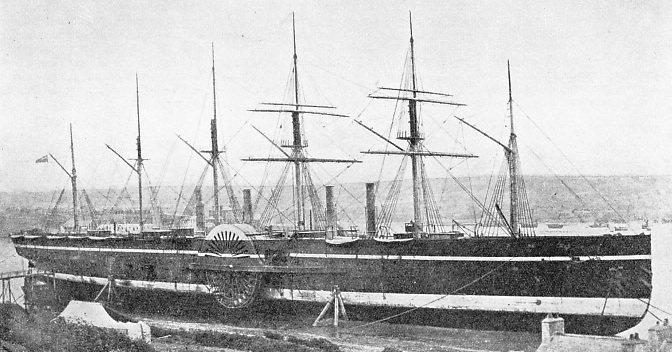

The weight of each paddle wheel was ninety tons. The original wheels were 56 feet in diameter, but these were torn off by giant seas during a great gale in 1861. New and stronger wheels, 50 feet in diameter and with narrower floats, were later fitted and these lasted the life-

A 36-

The starboard crossheads were connected to their opposite cranks by single connecting rods. On the port side, however, the connecting rods from each crosshead were doubled. There were thus three connecting rods attached to each crank. Four jet condensers were arranged between the cylinders and contained horizontal air-

The valve rods of opposite cylinders were joined by a framework reciprocated by a link motion reversing gear. The propeller was carried on a shaft 150 feet long that weighed 60 tons.

The screw of the vessel was larger and heavier than any fitted to the Queen Mary, but it must be remembered that the giant of 1936 has four propellers. The earlier wonder-

The screw engines alone gave a speed of 9 knots and were supplied with steam by six boilers, each weighing 55 tons and cont-

In the days of the Great Eastern men had not learned to put their trust in steam alone. So this ship was provided with sails. Six masts carried a spread of 6,500 square yards of canvas -

A CONTEMPORARY PHOTOGRAPH OF THE GREAT EASTERN beached for examination. Her original paddle wheels were 56 feet in diameter and weighed 90 tons. These enormous wheels were torn off during a gale in the Atlantic in 1861. They were replaced with stronger paddles 50 feet in diameter. The paddle engines indicated 3,411 horse-

There were no fewer than twenty anchors and these with their chains and cables weighed altogether 253 tons. The passenger accommodation seems to have been ruled by considerations of quantity rather than quality. There were cabins for 800 first class, 2,000 second class and 1,200 third class passengers, and it is stated that as a troopship she could have carried 10,000 men. This last figure would appear to indicate a certain amount of overcrowding among the troops.

No mention is made in the ship’s records of swimming pools, sports decks, tennis courts, marble lounges or luxury suites. The ocean traveller of to-

In September 1861, during a great storm at sea, the Great Eastern came near to disaster. She encountered heavy seas when about 280 miles west of Cape Clear, Ireland. With the increase of the gale, the captain ordered the setting of sails to keep the head of the ship to the wind, but these had scarcely been set when they were blown to shreds.

After a heavy sea had struck the ship, a grating noise was heard in the paddle boxes and it was found that the port wheel had become bent and was scraping against the side of the ship. The other paddle was also smashed and the captain ordered the paddle engines to be stopped as there was a danger that the wheels would tear holes in the ship’s sides. The screw had been put out of action by the jamming of the rudder. The seas were described by eye witnesses as “running mountains high” with the ship rolling over on to her beam ends so that at times the decks were at an angle of 45°. The ship continued to roll in this fashion for many hours and practically everything movable on board was smashed to pieces.

Almost every cabin in the ship was flooded and a passenger gave the following account of the scene: “Many require a change of clothes and the hatchways of the baggage stores are opened. The scene that presents itself defies all description. The water has got in, and in sufficient force to float even many of the larger articles. The rocking of the ship had set the whole mass in motion; twenty-

Laying the Atlantic Cables

In this gale the paddle wheels were torn right off the ship, and the rudder post, a piece of iron 10-

It is noteworthy that during this gale a small sailing brig, the Magnet, of Nova Scotia, stood by the stricken steamer to render assistance if required. Eventually the Great Eastern limped into Cork Harbour.

Although the Great Eastern was not a commercial success either as a passenger or a cargo vessel, she did much useful work as a cable ship. An Atlantic cable had been laid in 1856, but it subsequently failed and the Great Eastern was chartered to lay a new cable in 1865. The ship left Yalentia, Ireland, at the end of July 1865. On August 2 the cable broke after 1,200 miles had been paid out.

The following year, on July 13, the Great Eastern again left Ireland in an attempt to complete the cable partly laid and at the same time to lay another new cable. The steamer laid the new cable across the Atlantic in fourteen days. She then steamed eastwards again and on August 13, 1866, made her first attempt to recover the broken end of the cable that had been lost in the previous year.

After many failures the cable engineers were successful in finding the broken end on September 2. The end of a new cable was spliced on and the remainder of the cable laid. Prominent in these cable-

After the conclusion of her cable-

An unlucky ship, she had carried a corpse on board throughout her career. On opening the double bottom of her hull the ship-

SECTIONAL PLANS OF THE GREAT EASTERN. The upper photograph shows a plan of the spar deck, illustrating the positions of the five funnels and six masts. The lower sectional plan of the Great Eastern shows the screw engines placed aft and the paddies with their engines amidships. The main and longitudinal bulkheads formed spaces, some of which were used as bunkers to carry 10,000 tons of coal.

You can read more on “The Biggest Sailing Ship of her Time”, “Cable Ships at Work” and the “Laying the Ocean Cables” on this website.

You can read more on “The First Atlantic Cable” in Wonders of World Engineering