© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Romance of the “Mauretania”

Holder of the Blue Riband of the Atlantic for over twenty years, the Cunard liner “Mauretania” was one of the most remarkable ships ever built. When she was broken up after a long and proud career, her loss was felt keenly by thousands of ship lovers all over the world

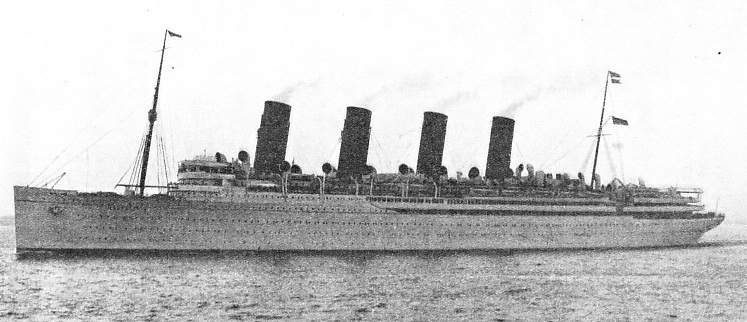

THE GRACEFUL LINES OF THE FAMOUS OCEAN GREYHOUND, the Cunard liner Mauretania, are still remembered by many transatlantic travellers, and by inhabitants of Southampton and the neighbouring coasts. A quadruple-

THE establishment of faster runs on the Atlantic crossing has always proved a difficult problem -

All these problems, and more, were presented to the men responsible for one of the most remarkable ships of all time, the Mauretania, holder of the Atlantic record for more than twenty years and the sister of the Lusitania.

In 1897 the Blue Riband of the Atlantic had been won by a fine North German Lloyd steamer, the Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, of 14,350 tons gross, with 32,000-

The Cunard Company then announced that it would lay down two steamers of 30,000 tons to recapture Great Britain’s position in the Atlantic trade. The building of these two ships was to be carried out with the assistance of the Government on terms that would keep them under the British flag and provide a pair of fast auxiliary cruisers in the event of war.

These were the circumstances that governed the building of two of the most famous of all ships -

The agreement between the Cunard Company and the Government was reached in July 1903, and for two years plans were discussed, rejected and re-

Accordingly a large number of experiments were carried out with models in the Government testing tanks. The models were one-

Then there was the all-

Another innovation that was suggested but not adopted until many years afterwards was the use of oil fuel for firing the boilers. In the early years of the century, supplies of fuel oil could not be regarded as absolutely reliable, and its cost was high. The ultimate supremacy of oil firing was, however, foreseen and the bunkers and furnaces in the Mauretania were so built that conversion to liquid fuel was possible without undue difficulty.

For months the preparatory work went forward. Every aspect of the work was discussed and agreed upon by committees of experts. The city of Liverpool also took a hand in preparing for the new Cunarders, and nearly 250,000 tons of material were dredged from the bed of the River Mersey alongside the famous Princes Landing Stage. New moorings were also provided in the Mersey.

Finally, on September 20, 1906, the Dowager Duchess of Roxburghe broke the traditional bottle of champagne on the stem of the giant vessel and the hull slid into the waters of the Tyne. The Mauretania was built by Swan, Hunter and Wigham Richardson, and was fitted with Parsons steam turbines. The gross tonnage of the Mauretania was 31,938. Her overall length was 790 feet, her beam 88 feet, moulded depth 60 ft 6-

There were seven decks amidships and two orlop decks fore and aft. The hull was subdivided into 175 watertight compartments in addition to the protection afforded by the cellular double bottom extending to above the bilge keels. There were fifteen watertight bulkheads, and of the watertight doors thirty-

The turbine machinery of 68,000 shaft horse-

The First Trials

The total heating surface of the boilers was 159,000 sq ft, the grate area 4,060 sq ft and there were 192 furnaces into which the “black squad” were required to shovel 1,000 tons of coal a day. The bunker capacity was 6,000 tons, enough for one Atlantic crossing with an allowance for bad weather.

The Mauretania was converted to oil-

Thirteen months after her launch the completed Mauretania was scheduled for her steam trials, but as she was so much a “vast experiment” her builders indulged in yet another departure from routine. Five days before she was due for the all-

Willing hands fed those roaring furnaces, and the four giant turbines hummed in harmony as the stem of the great ship clove the seas at speed for the first time. Faster and faster the quadruple screws drove the huge vessel, at a speed never before attained by an ocean liner. And then the telegraph rang in the engine-

A redistribution of weight cured that trouble for all time, and on October 22, 1907, the Mauretania left the Tyne for her official trials, which began on November 5, after Scotland had been rounded. Day and night, steaming continuously through wind and rain, the new Cunarder covered 1,216 miles at an average speed of 26.04 knots. Part of that run was accomplished at a speed of 27.36 knots.

Then followed other speed and turning tests with highly satisfactory results. With rudder hard over and all turbines full ahead, the turning circle was only three and three-

Eleven days after her final trials the Mauretania left Liverpool on her maiden voyage to New York. The official timing of that voyage was: “Length of ocean passage, 5 days 5 hours 10 minutes. Average speed, 22.21 knots.” In the preceding September the Lusitania had already run her maiden voyage to New York at an average speed of 23.01 knots, with a return voyage at 23.993 knots. The Blue Riband had been regained for Great Britain.

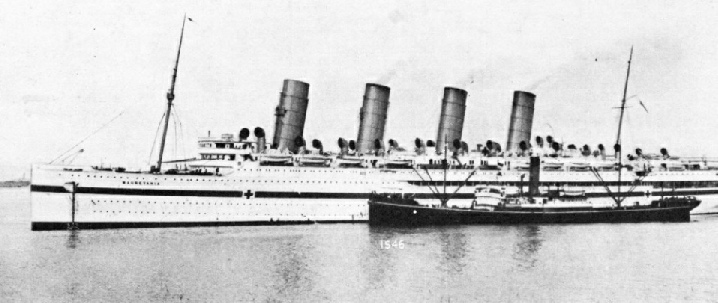

CONVERTED INTO A HOSPITAL SHIP during the war of 1914-

No immediate record was achieved, however, by the Mauretania, and with good reason. At 7.30 in the evening of Saturday, November 16, 1907, the liner left Princes Landing Stage. Liverpool, and there followed a wonderfully smooth passage through the night to Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland, reached at nine o’clock on Sunday morning.

Two hours later, with additional passengers and mails on board, the Mauretania faced the might of the Atlantic Ocean for the first time. For just one hour on that wintry Sunday the great ship gave a demonstration of her speed and then she met the weather and drove through it.

A Stokehold Inferno

Those were the days when stokeholds were infernos of blinding coal-

Imagine the task of just one man -

Yet another spell for raking over the incandescent mass on the fire bars, and then that grim routine again and again for hours on end with floor plating turning this way and that, rising and falling with sickening movement as the mighty vessel fought storm or ocean swell. But the Irishmen from Liverpool stood up to all this. They were the finest firemen in the world, to be supplanted only by the deadly precision of the mechanical oil pump and the swirling blasts of rotary air fans. At noon on Sunday, November 17,

the Mauretania began her wrestle with the Atlantic rollers and by noon of the following day she had covered 571 miles of her maiden voyage. The struggle with the ocean then entered an even fiercer phase. Great seas broke over the bows, and to the man in the crow’s nest aloft the great ship appeared dimly outlined below in a smother of spray, dwarfed by the gigantic seas, only the four funnel tops appearing as islands in a world of water. Picture the great stem lifting clear upwards a full 60 feet to be buried into the next mountainous sea by the mighty thrust of those giant turbines drawing hungrily on a roaring volcano of steam from battery upon battery of boilers in the depths of the great hull.

As the seas crashed on bulwark and plating the roaring avalanches of water tore at everything in their path. A spare anchor, a trifle of only 10 tons, was wrenched free from the forecastle head and began to beat a devil’s tattoo on the deck below it. But this was no joking matter -

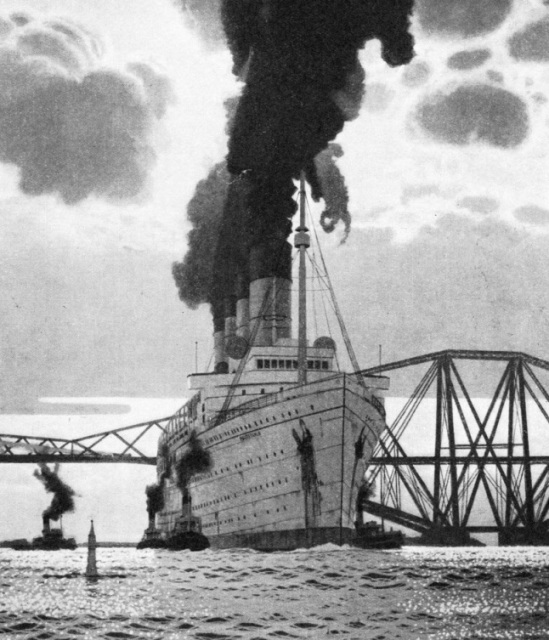

THE GREAT CUNARDER’S LAST VOYAGE. This striking impression of the Mauretania, passing the Forth Bridge on her way to Rosyth to be broken up, is reproduced from the painting by Charles Pears, R.O.I. The original painting is in the Queen Mary, the vessel which carries on the fine tradition established by the Mauretania. The well-

On Tuesday at noon the log showed a run of 464 nautical miles for the twenty-

After a brief stay among the skyscrapers the ship turned about for England. She left New York for Liverpool at 1.35 pm on Saturday, November 30, and arrived in the Mersey after a run of 5 days 10 hours 50 minutes, at an average speed of 23.69 knots. The time on the ocean portion of the return passage was only 4 days 22 hours 29 minutes, and that despite fog and bad weather. One more Atlantic round voyage she made in 1907 at much the same average speeds, and then began a wonderful series of journeys during which the liner kept time with marvellous regularity.

The Mauretania was a hard-

She encountered her first taste of propeller trouble in May 1908, when bound for New York. One of the propellers hit submerged wreckage and a blade was torn off. With three good propellers she completed that voyage and, still in that condition, made eight more round voyages at a speed approaching her average, except for one eastward passage, which was made at only 18.72 knots.

In October 1908 the Mauretania was taken out of commission for her annual overhaul, and in the following January she set out for New York with a set of new propellers, four-

RMS MAURETANIA

Launched: September 20,1906

Gross tonnage: 31,938

Overall length: 790 feet

Beam: 88 feet

Moulded depth: 60 ft 6 in

Draught: 36 ft 3 in

Shaft horse-

Designed speed: 25 knots

Highest average speed: 27.22 knots

Bunker capacity (coal): 6,000 tons

Complement: 3,103

For the next three years the Mauretania ran to and fro across the Atlantic, with only a short break for her usual annual overhaul. During that period she made eighty-

Of the forty-

On Active Service

So the Mauretania earned an unsurpassed reputation for speed and reliability. For two more years she continued to carry emigrants from Europe to the New World, business men, celebrities and tourists on their several errands.

On August 1, 1914, the Mauretania sailed from Liverpool on her westward voyage. Four days later she received wireless instructions to make with all speed for Halifax, Nova Scotia. Great Britain had declared war on Germany. The Mauretania had been specially built to permit the mounting of 6-

The Mauretania, however, was never used as an auxiliary cruiser. The use of large armed merchantmen as war vessels had been proved to be a mistake. The proof had rested largely in the fate of a German auxiliary -

The Mauretania was accordingly laid up until with the opening of the Dardanelles campaign an opportunity was found to use her. In May 1915 the Mauretania made her first voyage as a transport from Southampton, with 3,182 troops on board, bound for the Allied base of Mudros, on the island of Lemnos, in the Aegean Sea.

On May 7, 1915, her sister ship, the Lusitania, carrying passengers across the Atlantic to England, was torpedoed off the Old Head of Kinsale and sunk with the loss of 1,198 men, women and children.

By August 1915 the Mauretania had made three voyages to Mudros, carrying 10,391 officers and men. It was in the Medit-

Instantly the wheel was spun hard a-

Next followed yet another transformation for the world’s fastest liner. She was equipped as a hospital ship. Public rooms were turned into hospital wards packed with swing cots, and promenade and shelter decks were used as well. Three voyages the Mauretania made to Mudros and back, carrying 2,307 medical staff and 6,298 sick and wounded. With the evacuation of the Gallipoli peninsula the ship was paid off and her hospital equipment removed.

Once again the Cunarder became a transport, and in October and November 1916 she made two voyages from Halifax, Nova Scotia, to Liverpool, carrying 6,000 officers and men as part of Canada’s contribution to the struggle on the Somme.

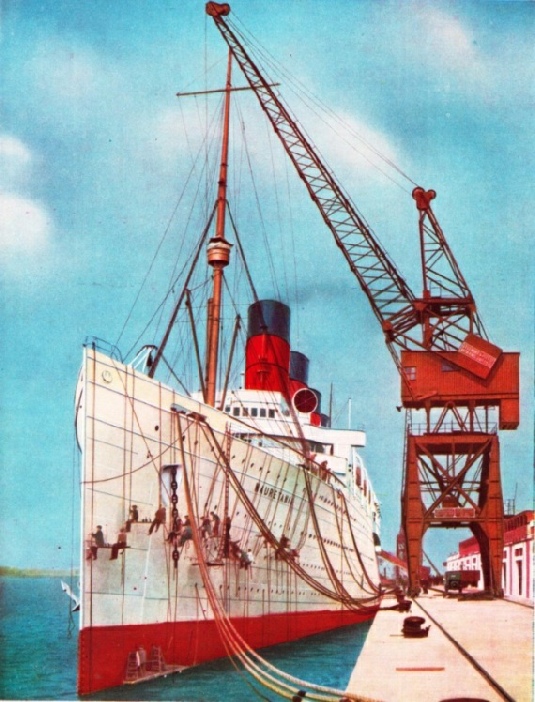

ONE OF THE MOST POPULAR TRANSATLANTIC LINERS was the Mauretania, shown being painted at Southampton in preparation for one of the cruises on which she was sometimes employed. A quadruple-

During the whole of 1917, Great Britain’s blackest year of the war, the Mauretania lay up at Greenock, but early in 1918 she was again commissioned as a transport, this time to bring American troops over to France. The work went on for seven months steadily reinforcing the Western front with divisions from the United States. News of the war’s outbreak had been flashed to the Mauretania on the high seas, and in the same manner she received notification of the Armistice. Thereafter followed a period when the liner’s services were required to return men to their homes, and on May 27, 1919, she was finally paid off and handed back to her owners.

Then followed a bad period in the life of the Mauretania. No war veteran, whether man or ship, was in best shape to face post-

Following labour troubles and difficulty in obtaining good coal, the ship’s fortunes were increased in July 1921 by an outbreak of fire that gutted all the first-

Conversion to Oil

That fire was a blessing in disguise, for in addition to repairing the damage the Cunard Company decided to convert the liner to an oil-

In that year the Mauretania made eleven round voyages across the Atlantic Ocean and twelve more in the year following. Her average speed was beginning to approach pre-

In 1926 the interior of the Mauretania received considerable attention. One hundred staterooms were modernized and public rooms were redecorated and refurnished. Two years later her engine-

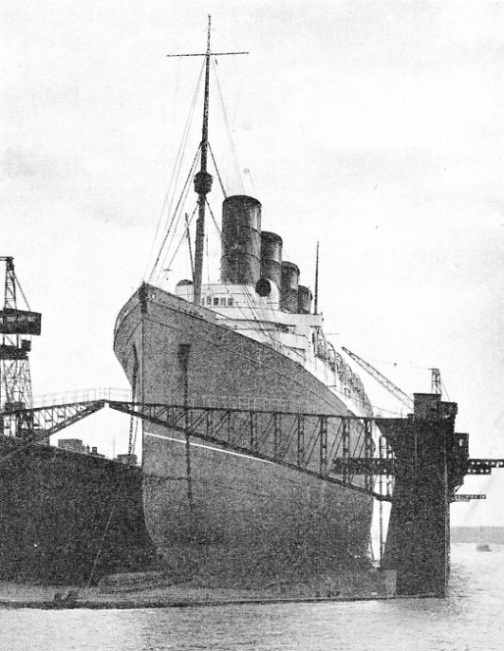

IN THE WORLD’S LARGEST FLOATING DOCK, at Southampton, the Mauretania was often overhauled all through her career. The floating dock, which has a lifting power of 60,000 tons, is fully described on page 1050. The Mauretania had an overall length of 790 feet, a beam of 88 feet and a moulded depth of 60 ft 6-

No queen can reign for ever, and the inevitable young rival was now due to take up the sceptre. In July 1929 the new German liner Bremen made the passage from Cherbourg to the Ambrose Light in 4 days 17 hours 42 minutes at an average speed of 27.9 knots. This was 1½ knots faster than the Mauretania’s best; but the gallant old ship was not to be ousted without a struggle.

On August 3, 1929, the Mauretania left Southampton for Cherbourg and New York with orders to do her best. Propeller revolutions varied between 205 and 210 a minute, and the engines were designed to give only 180. She did that voyage at an average speed of 26.9 knots, and her own Atlantic westbound record was broken by five hours. The Bremen had conquered by 4½ hours, but the German had been favoured by the weather. For the Mauretania it was a defeat to be proud of. On the passage home she averaged 27.22 knots, another record voyage.

That was in 1929 and still the wonderful old ship had years of useful life ahead of her, fast passages on time with the now popular cruises at intervals. In addition to her war service, the Mauretania made 319 voyages.

The last voyage of the famous liner, from Southampton to Rosyth, in the Firth of Forth, began on July 1, 1934.

On board the mighty Queen Mary there hangs a fine picture of the Mauretania, depicting her at Rosyth, surrounded by tugs, with the Forth Bridge as a background, and a funeral plume of black smoke rising into clouded sky.

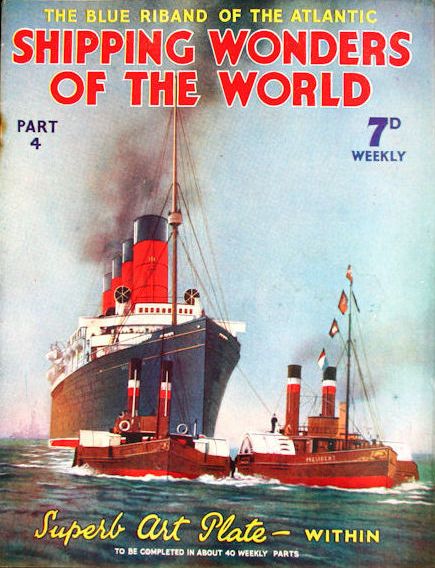

The Mauretania also featured on the covers of Part 4 and Part 19 of Shipping Wonders of the World.

The cover of part 19 is the same as the colour plate illustrated above.

“Our cover this week shows the famous Mauretania leaving the Tyne on October 22 1907, to be taken over by the Cunard Line.”