© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Part 16

Part 16 of Shipping Wonders of the World was published on Tuesday 26th May 1936.

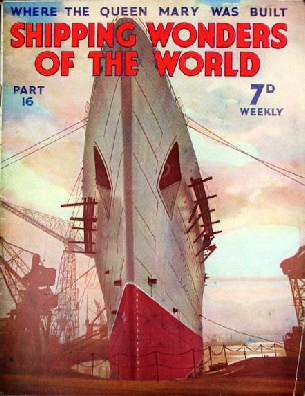

It included a centre photogravure supplement featuring the RMS Queen Mary, which formed part of the article on Where the Queen Mary Was Built.

The Cover

This week’s cover shows the Cunard White Star RMS Queen Mary in the early days of her construction when she was in the fitting-out basin at John Brown’s Yard at Clydebank.

Contents of Part 16

The Mighty Amazon

Concluded from part 15

Floating Aerodromes

This chapter discusses the evolution of the aircraft carrier, which, although it has been a unit of the Royal Navy for more then twenty years, is still an experiment.

The article is the fifth in the series The Navy Goes to Work.

Table of Aircraft Carriers

This interesting table is reproduced from the article. It lists all the carriers in the Royal Navy, including the Ark Royal, which had been laid down in the preceding year. All these carriers are described and or illustrated in the chapter.

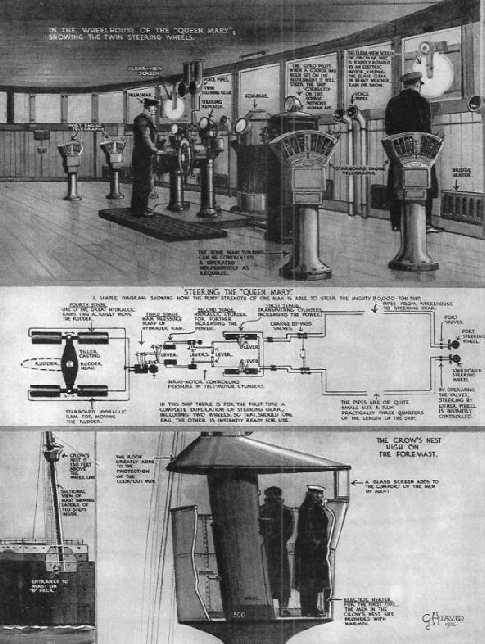

The Wheelhouse of the Queen Mary

The Queen Mary was the first ship to be fitted with twin steering wheels in the wheelhouse; should anything go wrong with one set a change over can be made in a few moments.

The second of the three diagrams shows how the man-power at the wheel is increased stage by stage until the gigantic hydraulic rams move the 140 tons rudder. By the aid of the Sperry Gyro pilot the Queen Mary can also be steered, when set on a course, without a helmsman. The Sperry Gyro pilot will keep the ship’s head on that course in calm or storm.

The third diagram shows the features of the crow’s-nest . Reached by climbing 110 steps inside the hollow steel foremast, the nest, which is 130 feet above the water-line, has a glass weather screen.

The Queen Mary: photogravure supplement

JOHN BROWN’S GREATEST TRIUMPH, the 80,000 tons RMS Cunard White Star liner, Queen Mary, in the fitting-out basin at Clydebank. The fitting-out basin is for John Brown’s own use, and is equipped with cranes lifted up to 150 tons and able to take the largest ships. It is known as the Clydebank Tidal Basin, and has an area of over five and a half acres, is 900 feet long by more than 300 feet wide. It has a minimum depth, at low water on ordinary spring tides, of 30 feet.

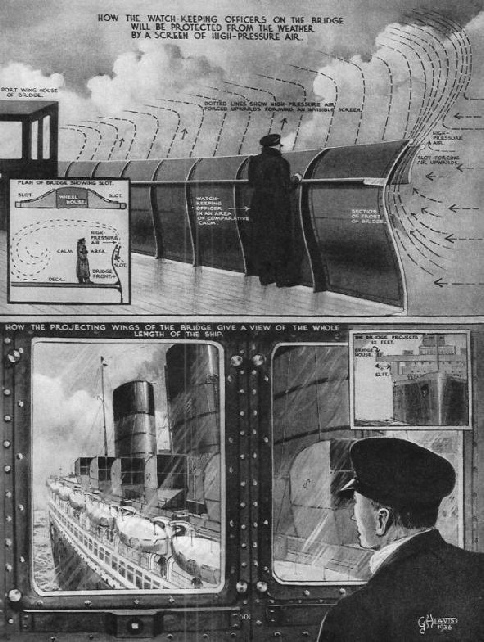

The Queen Mary’s Bridge

An interesting feature of the Queen Mary’s bridge is a slot that runs to port and starboard of the wheelhouse to the wing houses. This slot consists of a curved strip of iron supported out beyond the front upper edge of the bridge. It has been designed to create a screen of high-pressure air to protect the bridge staff against the rush of air. The wind strikes the front of the bridge and passes through the slot, and the narrowing nozzle increases the speed of air to such an extent that an invisible screen is formed along the greater part of the bridge. So strong is the pressure of air thus created that not only wind but also rain and snow are deflected over the heads of those on the navigating bridge. The bridge of the Queen Mary is also notable for the twelve feet overhang which projects beyond the sides of the ship. This makes it possible for the navigating staff to see the whole length of the ship from either the port or starboard wing house.

|

Laid Down |

Converted |

Length (Feet) |

Displ. (Tons) |

Speed (Knots) |

No of aircraft |

|

|

1914 |

1918 |

567 |

14450 |

20¼ |

15- |

|

|

1915 |

1915 |

786 |

22450 |

31 |

35 |

|

|

1913 |

1924 |

667 |

22600 |

24 |

21 |

|

|

1918 |

N/a |

598 |

10850 |

25 |

15 |

|

|

1915 |

1928- |

786 |

22500 |

30½ |

48 |

|

|

1918 |

1915 |

1928- |

786 |

30½ |

48 |

|

|

1935 |

N/a |

N/k |

N/k |

N/k |

N/k |

Contents of Part 16 (continued)

The Biggest Sailing Ship of Her Time

Although she did not achieve the success which was expected of her, the Great Republic is generally regarded as the masterpiece of her famous builder, Donald McKay.

This chapter is the sixth article in the series Speed Under Sail.

Where The Queen Mary Was Built

Famous for having built ocean greyhounds and the world’s largest battle cruiser, John Brown’s yard at Clydebank reached the peak of its achievement with the construction of the Cunard White Star RMS Queen Mary. The Queen Mary is the logical successor of a line of famous ships built at Clydebank. Among the great ocean-going liners built there you have only to recall the Lusitania, the Aquitania, and the Empress of Britain. Famous warships include the world’s largest, HMS Hood (42,000 tons), HMS Repulse, and HMS Barham. Frank Bowen not only tells us something of the history of John Brown’s achievements, but also gives interesting information about the preparations that were made for the building and the launching of the Queen Mary.

The Queen Mary (photogravure supplement)