© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

House Flags and Funnels

The fascinating story of the many-

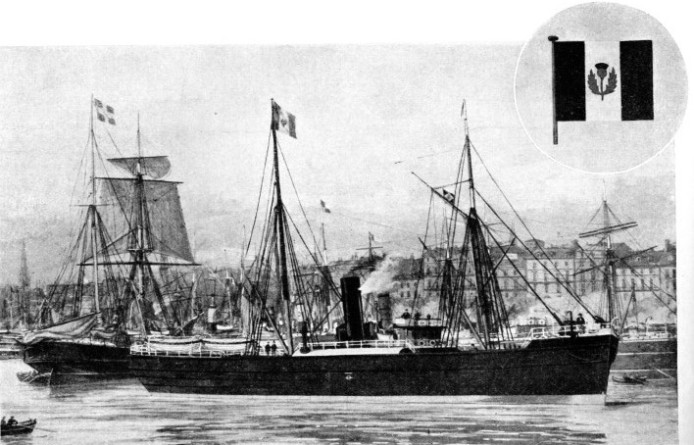

THE YEARS HAVE NOT CONDEMNED many of the famous old British house flags worn in the days of sail or steam and sail, and they fly from the masts of modern ships. The illustration shows the S.S. Niobe, that belonged to the J. and P. Hutchison Line, at Bordeaux, in 1885. The company is now part of the Moss-

THE custom of flying a house flag as the distinguishing signal of a merchant vessel’s owner is of later origin than that of wearing national flags by Royal or State-

The meaning of the term “house flag” is in dispute. Purists in flag matters maintain that it applies only to the flag of an owner whose business is primarily ship-

Others maintain that this definition is too narrow, and that it would debar from inclusion in a list of house-

or main business of which is ship-

These debatable points are best left to the disputants. The present chapter will deal with some of the earliest flags flown, as a modern house-

In the first recorded instance, national or Royal and private ownership were as closely connected in the flag as were the company’s and the State interests in the ships. The first of the Merchant Venturer or Chartered Companies were deliberately fostered by the Crown, because it was wisely realized how closely their interests were allied. Privately-

Under the grant, the members of the company were allowed (or ordered) by the Queen “to set and place in the tops of their ships and other vessels the Arms of England with the Red Crosse over the same”. To show the Red or St. George’s Cross over the Royal Arms, the Heralds gave the correct edge or “fimbriation” of white to the cross. The result was certainly a beautiful flag, well worthy of being the first recorded instance of a Merchant Service house flag. It is the first illustrated in the Colour Plate shown below.

The Gynney and Bynney (Guinea and Benin) Company of the African Gold Coast trade was another of the earliest Chartered Adventurers, and its flag (Colour Plate, 2) also incorporated the St. George’s Cross. Incidentally, it was the gold the company’s ships brought from Guinea that was first stamped into guineas and introduced the word into the English language. We find a deviation from the St. George’s Cross in a custom quickly established of using as a house flag the coat of arms granted by the College of Heralds for other and normal use. Some examples of these early devices survive in the house flags of the descendant companies.

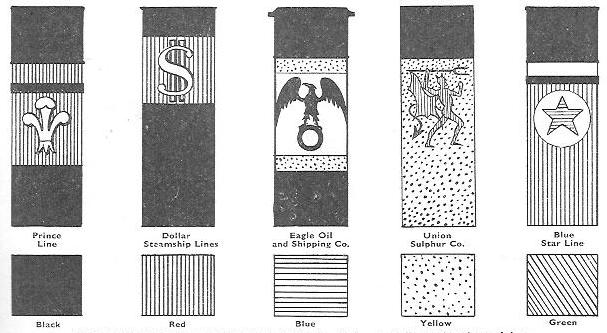

THE STANDARD HERALDIC COLOUR KEY, below the funnels, indicates the colours of those shown above and elsewhere in this chapter.

It is believed that the Hudson’s Bay Company can claim the proud distinction of being the oldest continuously existing firm of shipowners and traders. It now has two house flags. One is a flag picture (Colour Plate, 3) of the original coat, crest, supporters and motto granted in 1670; the other is a commonplace modern Red Ensign, “defaced” with the white initials H.B.C. The company was formed for the primary purpose of fur trading, and its flag depicted the main fur-

Another of these flags derived from the coat of arms and still flying (Colour Plate, 4) is that of the Carron Company, incorporated in 1775. Its device also clearly shows the basis of its business and Royal Charter, as carronade and munition makers. [A carronade is a large-

The flag of the Honourable East India Company (Colour Plate, 5) went through various changes in the number of the red and white stripes that it carried. At one time it had an up-

Early House Flags

Before leaving these flags of the old Chartered Companies, we must mention an early flag (Colour Plate, 6) designed to depict in a fine heraldic form the intention and aspirations of the owners.

The ill-

When the East India Company lost its monopoly and sold its fleet, many of the ships were bought by firms that had been building for, and in some instances chartering to “John Company”. These firms continued in the Eastern trade and many built up great businesses.

Duncan Dunbar, whose father had owned a small brewery in Limehouse, first went into shipping to cheapen the cost of exporting his beer to India. When he died he was the richest shipowner and had the largest fleet in the country. His flag (Colour Plate, 7) showed a rather distorted version of the Dunbar coat and crest, although irreverent seamen declared the design was from his beer-

When Dunbar died, the management of the ships was taken over by the firm of Gellatly, Hankey and Sewell, which replaced the Dunbar flag with its own (Colour Plate, 8). It is an amazing instance of the apathy in recording or preserving house flags that the flag of Dunbar, the greatest shipowner of his day, was completely forgotten and the details of it were lost, only to be rediscovered in recent years.

Other firms which took up the shipping trade of the old East India Company seem to have reverted to the first practice of the Chartered Companies, by having a red cross incorporated in their flags.

One of these firms had a long and curious history linking the present with the distant past. Green and Wigram were joint owners of Blackwall Dock, and built ships both for the East India Company and for themselves, either as partners or as separate owners.

Their first ship hoisted as house flag a plain St. George’s Cross on white, which was (and is) the distinguishing flag of an Admiral in the Royal Navy. When the ship put into Spithead, the Admiral there heatedly ordered the flag to be hauled down. Although this was done, it was quickly re-

HISTORIC FLAGS AND FUNNELS

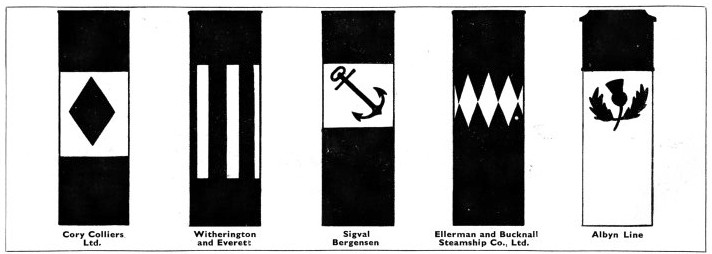

1. Levant Company (1581); 2. Guinea Company; 3. Hudson’s Bay Company; 4. Carron Company; 5. East India Company; 6. Scottish “Darien” Company; 7. Duncan Dunbar; 8. Gellatly, Hankey and Sewell; 9. Money Wigram (now Federal Steam Navigation); 10. R. and H. Green; 11. Joseph Somes; 12. Geo. Marshall & Sons; 13. T. & W. Smith; 14. Black Ball Packets; 15. Red Star Packets; 16. Black Star Packets; 17. Foley; 18. Skinner; 19. Nicholson, of Annan (before 1860); 20. Nicholson, of Annan (after 1860).

HISTORIC FLAGS AND FUNNELS

21. McCunn; 22. Baring Bros.; 23. Carmichael (“Golden Fleece”); 24. W. Gracie & Co.; 25. Gracie, Beazley & Co.; 26. Shepherd; 27. Shepherd; 28. Guion’s Black Star; 29. White Diamond (later Warren’s); 30. Red Star (Bernstein’s); 31. White Star (now Cunard White Star); 32. Aberdeen White Star (now Aberdeen and Commonwealth); 33. Brocklebank; 34. Allan Line (early steamers); 35. New Zealand Shipping Co.; 36. Beaver Line; 37. Canadian Pacific Line; 38. Orient (Sail); 39. Orient (Anderson & Green); 40. Orient (later form); 41. Sandbach, Tinne & Co.; 42. Peninsular & Oriental S.N.Co.; 43. British India S.N. Company; 44. General Steam Navigation Co.; 45. Moss Line; 46. Hutchison (Glasgow); 47. T. and J. Harrison; 48. Cunard (1840-

When the partners separated, Wigram, under the name of Money Wigram, retained the flag, and Green varied it by carrying the red cross through or over the blue (Plate, 10). Wigram’s flag continues to be flown now by its inheritors, the Federal Line. It comes again into the story of the Orient Line, as will be seen later.

Joseph Somes, George Marshall, and T. and W Smith were other important owners who carried on the former East India Company trade, and all had the cross in some form. The anchor in the canton of Somes’s flag (Plate, 11) is said to have been a right granted by the Admiralty in recognition of some piece of meritorious service during one of the Indian wars in connexion with the transport of elephants.

Marshall’s blue circle (Colour Plate, 12) is supposed to have been adopted to mark the fact that his ships were the first to follow a Great Circle sailing route to Australia. Smith avoided any clash with authority by making his cross blue (Colour Plate, 13). This flag, bearing the initials of Smith’s Dock Company, the Tyneside and Teeside ship-

The Americans first appreciated the commercial and advertising value of a house flag. It was with their Atlantic lines of sailing-

The first of these, founded in 1817, was the Black Ball Line (Colour Plate, 14), which became one of the most famous of its day. The Red Star (Colour Plate, 15), and the Black Cross (Colour Plate, 16) Lines were other famous packet lines following the same plan of using the flag description as the line’s name. On the discovery of gold in California in 1849 many of the American packet owners went into the Californian trade, carrying the gold-

Clipper Owners’ Flags

Huge profits allowed the owners to build some of the finest clippers that ever went round the Horn, and they had the extra advantage that this trade was strictly reserved for Americans as “coastal”. This law, which still holds, prohibits non-

The repeal of the Navigation Acts threw open British ports to foreign ships and brought a fleet of the finest American clippers into the Thames laden with tea from China in 1850. An immediate and intense rivalry began between them and the British clippers. At first the Americans scored heavily, obtaining double the freights for tea paid to British ships, and creating records as described in the chapter on Racing Clippers.

So rapidly were the British clippers improved, however, and so daringly were they sailed, that after only a few years of fast and furious racing the Americans were fairly beaten out of the field. By 1860 only British ships were left in the race for the bonus paid on the cargo of the first ship home.

The flags of many of the famous clipper owners are well known. Others have disappeared without trace and even now remain to be rediscovered -

Some others have only recently been rescued from oblivion and identified. Some are now given here, most if not all of them pictured for the first time in authenticated colours and designs.

Foley’s Dunkeld, Skinner’s Castles and Nicholson’s little Annan-

THE REAR-

Other winged or “flying” flags were those of McCunn’s Flying Horse and Baring Brothers’ Flying Star (Colour Plate, 21, 22). Barings are the great international bankers, and although no longer shipowners, they used to own some of the crack China clippers and have recently revived their old flag, which now flies daily over their City offices. Carmichael’s aptly named and flagged “Golden Fleece Line” (Colour Plate, 23) was in the forefront of the fast wool clippers, and W. Gracie and Co. and Beazley (the two joined later as Gracie, Beazley and Co., also had an important share in the Australian trade (Colour Plate, 24, 25). Shepherd had two flags at different times, although only one of them (with cross) is generally known now (Colour Plate, 26, 27).

It is strange that in spite of all the advantages and the dominance in the major ocean sea transport trade which the American lines secured in the ’fifties, few of their great packet and clipper lines carried on into steam or have survived into our days.

Rare exceptions include the Atlantic line of Williams and Guion’s Black Star (Colour Plate, 28) which went into steam to compete with British Atlantic steam lines, and Train’s White Diamond Line (Colour Plate, 29), which sold out and later became the Warren Line. There is no connexion between the old Red Star packet line (Bernstein’s) and the present Red Star Line, original owners of the Pennland, and Westernland, recently sold to a foreign company after the Government’s veto of purchase by a British company (Colour Plate, 30).

On the other hand many famous British house flags of sail are still worn by some of the finest steamers afloat, whether passenger, mail or cargo.

One of the most notable of these is the White Star (Colour Plate, 31), now merged with the Cunard as owners of the Queen Mary. The line began with a fleet of fast clipper ships carrying emigrants to the Australian gold diggings in the fifties. When that rush began to decline, the owners sold for £1,000 in 1867 the White Star flag and name to Mr. Ismay. In 1871 flag and name were extended to the new line of transatlantic steamers that has been prominent ever since.

Another White Star Line, known as Thompson’s or the Aberdeen White Star, owned the famous Thermopylae and other fine clippers in the Australian and China trades. The flag and firm carry on as the Aberdeen and Commonwealth Line (Colour Plate, 32).

The Brocklebank firm (Colour Plate, 33) can claim to be the oldest British shipowners still existing. It began with little brigs in the 1770’s, and has carried on ever since. Its steamers maintain the custom of flying the house flag at the foremast head, instead of in the normal place at the main.

Another early sail firm that continued the same custom into steam was Sandbach, Tinne and Co. (Colour Plate, 41). The origin of the firm’s flag (blue before white before blue) is of interest. In its early days, when the firm had no house flag, one of the West Indian ports made a rule that a house flag must be displayed by every ship entering or leaving port. The captain cut up the legs of his blue dungaree trousers and a white shirt, and made the required distinguishing flag.

Flying the French Tricolour

The well-

When the Allan Line went into steam, its steamers flew a pennant above the house flag. This practice was necessary -

Another well-

The Beaver Line of Canada (Colour Plate, 36) was another sail-

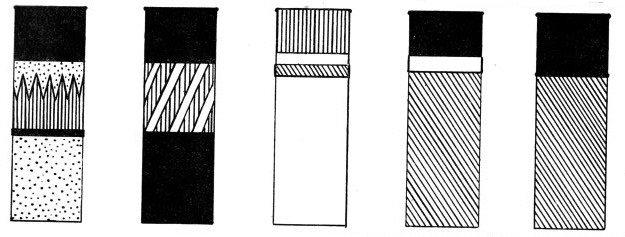

A VARIETY OF DESIGN is displayed in the colouring of these funnels which -

The Canadian Pacific existed as a railway company before it began to own steamships. When it ran its railway across Canada, the land on either side of the railway was divided up into square blocks, belonging alternately to the company and to the State. The State reserved its blocks for settlement. On the official railway map the squares were marked alternately red and white (red for State and white for railway). When, therefore, a house-

Another leading British line to continue from sail into steam was the Orient. Its history is linked with that of one of the oldest British flags -

The first Orient liner was a fine clipper ship built for the Australian trade but used as a troopship in the Crimean War. The flag then was a white saltire on blue -

That ideal of an easily distinguished flag having a history and tradition behind it is finely exemplified in the flag of the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Co. -

Over 100 years ago, Willcox and Anderson, two London shipowners running a few small brigs to the Spanish Peninsular ports, espoused the cause of the Queen of Portugal during an insurrection against her. They chartered or lent their ships, ran munitions, and armed one vessel as a warship. One of the partners risked on several voyages the firm’s fortunes and his own life.

The insurrection was finally quelled, but almost at once the Carlist War in Spain broke out, and again the partners helped a Queen, this time the Queen of Spain. When she, too, was firm on her throne, the partners’ services were rewarded, and in recognition of this piece of history the house-

When the partners formed the Peninsular Steam Navigation Company, it flew the same flag. The practice has continued ever since, and the flag is now flown over the P. & O. Liners.

The British India, associate company of the P. & O., owns about 114 oceangoing mail, passenger and cargo liners totalling some 683,000 tons, one of the largest fleets under its own flag in the kingdom, if not in the world. No record remains as to origin or meaning of its flag (Colour Plate, 43).

There is an old “yarn” on this, however, worth the telling, even if unauthenticated. It is to the effect that the founder partners in India, being as good Scots as their Mackinnon and Mackenzie names suggested, instructed a flagmaker to make sets of flags for their first ships, taking the St. Andrew’s Cross as design and cutting a triangle from the fly to distinguish it from the national flag. The fly is that part of the flag farthest from the staff.

One of the partners drew an outline to indicate the flag’s shape and position of the Cross, but the ignorant Sassenach flagmaker made the saltire a red-

The oldest British firm of owners of sea-

Origin of Cunard Flag

The General Steam Navigation Co. recently acquired the Moss-

Another Maltese Cross flag, of the Harrison Line, was adopted for other reasons than Maltese trade, in which it has never engaged. The first sailing ship of the firm was named the Knight Templar and the cross was chosen to fit this name (Colour Plate, 47).

There is no better instance of how a flag’s origin can be lost in oblivion than that of the Cunard flag (Colour Plate, 49). Long and wide investigation with every assistance from the Cunard Company, has failed to establish facts, but the following is a reasonable explanation.

When Samuel Cunard came to England from Halifax to try for the Atlantic steamer mail contract, he was introduced by the London secretary of the East India Company to Mclver of Liverpool, and to Burns of Glasgow, a Scottish owner of coasting and Irish trade sailing vessels. Burns’s efforts and influence were mainly instrumental in raising the required funds. When the line was formed, Cunard, in compliment to Burns, adopted his sail house flag of a narrow white-

This double-

When in Halifax, Samuel Cunard was agent of the East India Company, the crest of which was a rampant lion bearing a crown in its paws. The company’s cadet college at Haileybury (Herts) took the same crest, making sufficient and appropriate heraldic “difference” by placing the crown on the head and a scroll between the paws. When the Cunard was formed into a limited liability company about 1880, a company seal was required. The company, being familiar with East India Company’s crest and recalling the London secretary’s help, took as its seal device the rampant lion, making a “difference”, as Haileybury did, by placing a globe in the paws.

The Burns Company of Glasgow (now the Burns-

The Ellerman firm appears to have been the first to institute a symbol of victory flown over the flags of lines it had bought up -

There is less of history, and still less of its verification, in the story of funnel markings. In the early days of steamers, burning any kind of coal with imperfect combustion, it was natural that funnels should nearly all be painted black to avoid showing the smoke grime. But owners then had no tradition or rule of funnel colours or markings and kept no record of them. The only clues to them now are in old paintings and prints. These, in fact, show how irregular or erratic a line’s funnel colours were.

The P. & O., for example, did not always have the black hulls and funnels and buff upperworks now so widely known over the whole of the Eastern hemisphere. Some of its first little paddle steamers had white or red funnels with black tops; and before the Suez Canal opened, the ships from Egypt to India had white hulls.

There was therefore an old precedent for the colouring of the Strathmore and two other “Straths” of the P. & O. These luxury liners are known as “the White Sisters”, because both ships are painted in gleaming white from the red “boot-

There is, however, one line that takes its name from its ships’ funnels, and there is a well authenticated tale of how the funnel colour was first adopted.

The owner of the first steamer bought by Holt’s had just died. In accordance with ancient sea custom (still followed in rare instances) a blue band had to be painted round the hull as a sign of mourning.

The ship, bought as she lay, had on board numerous drums of blue paint. The paint was used up on the funnel, and the same distinctive shade of blue has ever since marked the vessels of the Blue Funnel Line (Colour Plate, 56).

Bibby Bros., one of our oldest shipping firms, founded in 1807, and the Leyland Line have funnels of an unusual “salmon pink”; and both, curiously, had for many years the same plain red flag. The Bibby family crest on one (Colour Plate, 57) and cross through the other (Colour Plate, 58) now distinguish them. There are many more flags of historic origin and meaning, as in Shaw, Savill & Albion’s adaptation of the first Maori national flag (Colour Plate, 59), and the Anchor Line’s four links of cable representing the four founder brothers (Colour Plate, 60).

As the flags were worn by sail and steam, by vessels with sing le, compound, triple expansion, turbine, oil-

le, compound, triple expansion, turbine, oil-

“FLYING” THE FLAG. Hillman’s Airways, Ltd, run a service from London to connect with the General Steam Navigation Company’s pleasure steamers at Ramsgate. The aeroplane in the picture can be seen with the steamship company’s house flag On her fuselage.

The General Steam Navigation Co., founded with paddle-

Some Atlantic liners carry aircraft to speed up the last lap of the passage for mail or passengers. And in January, 1936, the Union Steam Ship Company of New Zealand opened a daily air service between North Island and South Island.

In this practical and prosaic age, it is good that we can still preserve a measure of sentiment; and in few ways can we better preserve, treasure and perpetuate our maritime sentiment, history and tradition than in the house flag symbols of the Merchant Navy.

You can read more on “Flags and Ensigns”, “Romance of the Racing Clippers” and

“Signalling at Sea” on this website.