© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Flags and Ensigns

Much misapprehension exists about the flying of flags and ensigns at sea and on land. The circumstances in which any flag may be flown at sea, however, are clearly laid down by law. The flying of certain flags on shore is governed by unwritten laws

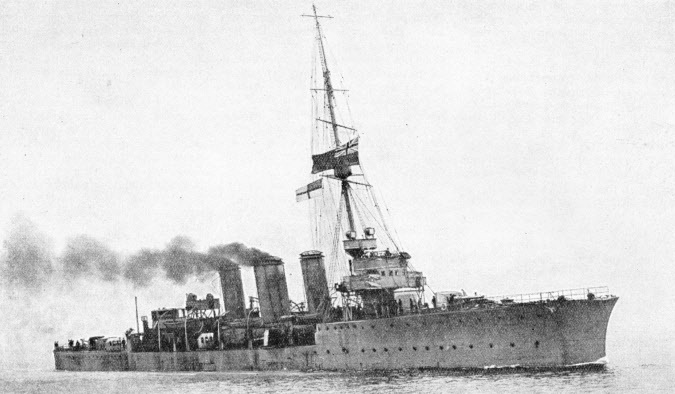

A SHIP OF THE ROYAL NAVY normally flies the White Ensign. During the war of 1914-

THE British Empire has such a large variety of standards, ensigns and jacks that it requires an expert to explain the appropriate uses of each. A disadvantage of British flag practice is that no law exists as to what may or may not be done on land, although there are strict rules, sometimes rigidly enforced, concerning the use of British colours afloat.

It is not fair to compare the British Empire with other countries in this connexion, because conditions vary considerably. In Germany, for instance, although the national emblems have undergone several changes of late, the decrees on flag procedure and observance have been clearly laid down by the Chancellor. German merchant ships must by law wear the authorized jack as well as the ensign on all occasions, even when under way. Their boats, too, and all small craft such as tugs and fishing vessels, must do the same.

In the United States also there is a strict code for the proper display of the Stars and Stripes, including its use in street decorations and inside public buildings, at lectures and as a pall on the coffin of the dead.

France is another country in which flag procedure is simple, because the tricolour, blue, white and red in vertical bars, is the same when used afloat and ashore, as an-

The existence in the British Empire of three ensigns, the Red, the White and the Blue, is bewildering to foreigners who do not know how these different maritime flags originated nor why three distinct ensigns should be necessary in modem times.

The origin of these colours goes back a long way in the history of the Royal Navy. In 1625 the fleet was divided into the three squadrons, Red, Blue and White, distinctions which denoted the Centre, Van and Rear Divisions. In 1653 the precedence was altered to Red, White and Blue, and those were then the colours of the ensigns worn by the ships in the three separate squadrons up to the year 1864. From pictures that were painted in the intervening period we see that men-

Lord Nelson was a Vice-

By 1864, the fact of Her Majesty’s ships being liable to wear one of the three coloured ensigns had become absurd and anomalous, as well as expensive. It was therefore decreed that the Royal Navy was in future to be restricted to the White, the Royal Naval Reserve and certain privileged ships to the Blue, and the Merchant Service to the Red Ensign. In this way the Merchant Navy became entitled to what had up to then been the senior naval colour.

The White Ensign is allowed as a privilege, and by special warrant in every instance, to yachts of the Royal Yacht Squadron, and to no other vessels outside the Royal and Dominion Navies. Variations of the Blue and Red Ensigns, however, are numerous, and have not always to do with the Royal Naval Reserve or the Merchant Service. Public bodies such as the Board of Trade, Ministry of Transport, Customs and Lloyd’s are allowed to use the Blue Ensign, “defaced” with their own badge in the fly of the flag.

Yacht clubs of different denominations are privileged to adopt the Blue and Red Ensigns “defaced” with their club badges,but in every instance the privilege is covered by a special warrant. Other variations of the Blue and Red Ensigns occur in the ships of the various British Dominions, Colonies and Dependencies.

Thus every separate eventuality is legislated for and dealt with appropriately from the shipping point of view, and it is not till we turn to the land that real doubts about British flags begin. Over and over again private individuals have asked what national flag they may fly at their residences.

The answer is in truth quite plain. In the House of Lords on July 14, 1908, the Earl of Crewe said, “the Union Jack should be regarded as the national flag, and it, undoubtedly, might be flown on land by all his Majesty’s subjects”. And again, as recently as June 1933 the Home Secretary stated in the House of Commons that “the Union flag is the national flag, and may properly be flown by any British subject on land”. It has been stated that the use of the White and Blue Ensigns on shore, with a few exceptions, is improper. The Red Ensign, as it happened, was not mentioned in this connexion, from which it might be inferred that there is no objection to the use of this flag by private individuals ashore. The Red, the White and the Blue Ensigns are equally correctly described as “of His Majesty’s fleet”, so that logically the Red Ensign should be subject to the same limitations as the two others.

Certain maritime bodies are entitled to the Blue and Red Ensigns slightly varied by their different badges, and through custom and long association they have come to use these ensigns at their shore headquarters and other stations. Examples of such are the yacht club premises round the coasts, the Customs offices at seaport towns and the lighthouses of Trinity House and other authorities. The Admiralty view seems to be that if private individuals also make a practice of flying marine ensigns, confusion is likely to follow. For instance, should a retired boatswain's mate of the Royal Navy hoist the White Ensign at his cottage on the cliffs, and should that cottage be adjacent to a naval signal station, legitimately flying another White Ensign, some misapprehension would undoubtedly be created.

Public opinion has been stimulated in recent years to condemn the once popular conception of loyalty that manifested itself in the festooning of the streets with Royal Standards and the displaying of them on private houses. It has been emphasized that the Royal Standard is the King’s personal banner, and may not be allocated to any other purpose.

A flag that flies in unique circumstances on land is the Admiralty emblem, consisting of the yellow foul anchor on a crimson field, hoisted above the Admiralty building in London. This flag is never hauled down, night or day.

To whatever degree people may be persuaded to depart from the restrictions imposed by the authorities, they must eventually be thrown back upon the statement that the Union flag is the proper one for all British nationals to display on land.

A sense of patriotism should ensure that the national colours are treated with proper respect in whatever circumstances they are displayed. Ashore or afloat, they shouldbe hoisted correctly. An unwritten law at sea interprets the showing of a national flag upside-

A sense of patriotism should ensure that the national colours are treated with proper respect in whatever circumstances they are displayed. Ashore or afloat, they shouldbe hoisted correctly. An unwritten law at sea interprets the showing of a national flag upside-

Except on occasions of national or public mourning, or of a private bereavement, the Union flag and the maritime ensigns should be hoisted as close up to the truck as possible, and the tack or line attached to the lower corner of the flag should be hau’ed tight against the mast. As often as not the tack is allowed to fly away in a generous curve, and this, even if it may pass as artistic, is certainly unseamanlike. When half-

HANDED OVER TO THE BRITISH, this German submarine is flying the White Ensign above the German Ensign. The relative position of the two flags is important, as it indicates surrender on the part of the lower flag.

You can read more on “House Flags and Funnels”, “The Navy Goes to Work” and “Signalling at Sea” on this website.