© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Glasgow: Scotland’s Premier Shipping Centre

Along the banks of the River Clyde from Glasgow to Greenock are situated some of the biggest shipbuilding yards in the world. With the development of her shipping activities Glasgow has risen from a small town to the sixth largest city in the British Empire

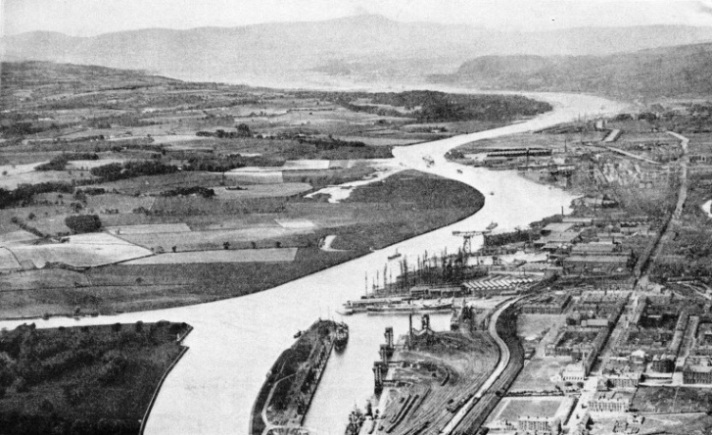

THE THE BIRTHPLACE OF MANY FAMOUS LINERS. Opposite the mouth of the small River Cart (left) are John Brown and Company's shipbuilding yards, on the north bank of the Clyde. In the foreground is the Rothesay Dock, which has a water area of 20½ acres. The width at the entrance is 200 feet and the quays have a total length of 6,134 feet.

OVER two centuries ago Glasgow was a minor seaport and as a Scottish town was completely overshadowed by her neighbour Edinburgh, which was then a capital without a rival. In those days, the Clyde was navigable only by small boats.

To-

How, then, did a small town on a shallow salmon river become a port of world-

out. The population of Glasgow alone, excluding her satellite towns on the Clydeside, has now passed well over the million mark. The river which gave to the world Henry Bell’s Comet in 1812 has given us the Queen Mary and H.M.S. Hood. Yet at the time the Comet was afloat, tiny as she was, she frequently ran aground on the innumerable shoals of the Clyde.

Among the many famous ships which have had their birthplace on the Clydeside were the first Cunard steamer to cross the Atlantic, the Britannia, and the beautiful two-

Glasgow, which began her commercial career as an exchange for sugar and tobacco, grew during the last century into the great transhipment place for huge consignments of coal, iron and other minerals. In addition to her shipbuilding activities, she is the birthplace of thousands of locomotives which run on railways all over the world. These, and a host of other industries, she owes entirely to the imagination and enterprise of those who first saw her unbounded possibilities as a great seaport.

Let us look back, and try to picture the Glasgow of two centuries ago. Unless we were set down in front of the ancient and unmistakable cathedral, with our backs turned towards the river, we would recognize nothing of the place. We would see no seaport at all.

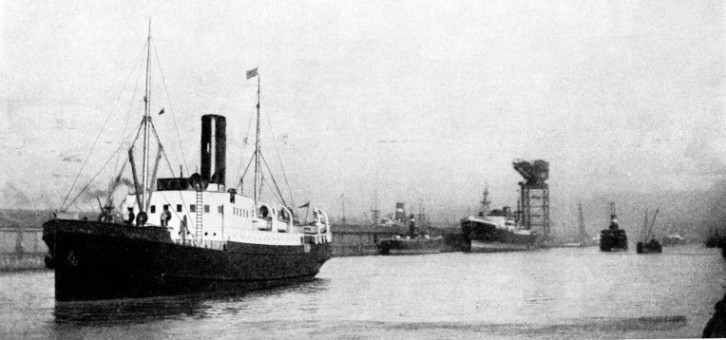

OUTWARD-

Tiny harbours such as Polperro and Boscastle, Cornwall, have more in common with the Glasgow of to-

There, in 1688, was founded Glasgow’s first harbour, which is known to this day as Port Glasgow. It was no fewer than eighteen miles downstream from the city which gave it its name. Even so, the early commerce of Port Glasgow was the beginning of Glasgow’s great reputation as a trading and industrial centre. Before that, Glasgow owed what importance she had simply to the fact that there were a big cathedral church and a cluster of houses existing in close proximity to a bridge stretching across the River Clyde.

Nearly a hundred years later the iron-

This gave more or less practical communication between the open sea and the Carron Ironworks near Falkirk. But the hundred and one great and small co-

So progress was made, first slowly, and then more quickly. Some idea of the manner in which Glasgow rivers was changed from a shallow stream, peopled by trout and salmon, into a deep and navigable channel, may be gathered from the chapter “Dredgers and Hoppers”. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the once brawling reaches of the lower Clyde were beginning to resemble the slow, narrow river of to-

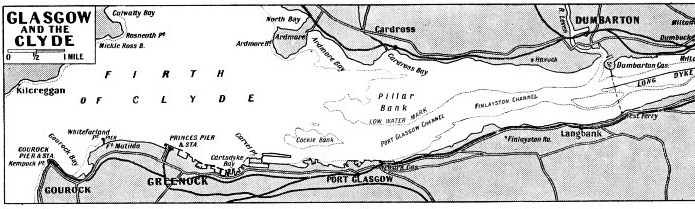

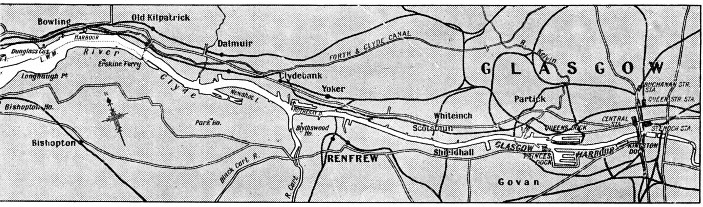

THE RIVER CLYDE is a scene of shipping activities of every description along its banks from Greenock to Glasgow Docks. The Firth of Clyde, with its mountains and islands, forms a beautiful approach to a great port. Greenock, on the south bank of the river, is the outpost of the Port of Glasgow. Here may be seen the first of the shipbuilding yards which line the banks of the river almost continuously. At Dumbarton, the River Leven, flowing from Loch Lomond, joins the Clyde, and opposite Clydebank the mouth of the River Cart made possible the launch of the Queen Mary. The Forth and Clyde Canal joins the Clyde at Bowling.

In 1858, the Clyde Navigation Trust was formed by Act of Parliament, placing the whole of the river, docks, and quays between Glasgow and Port Glasgow under one administration.

So after years of ceaseless dredging and occasional blasting, a minimum low-

One of the most striking features of Glasgow is the world-

The Broomielaw itself was there before the deepening of the channel — long before — for it was built in 1678. It is a strange and rather wonderful feature of the city, that long, busy quay running down the riverside, with great business houses rising almost on top of it, trains rumbling above its eastern extremity, the high, crammed buildings of the Gorbals frowning at it from across the water, and big steamers, bound for the other side of the world, lying in nearby docks. For three-

The names of past and present shipping companies seem to mutter and echo in the noises of the Broomielaw. The Blue Funnel Line and the Clan Line may jostle with the coastal steamers of the Burns and Laird Lines and of David MacBrayne Limited, whose plucky little red-

Opposite the western end of the Broomielaw lies the Kingston Dock, a tidal basin of 4J acres, with 2,367 feet of quays, which was opened in 1867. This is the oldest and smallest of the works which make up Glasgow’s huge dock system to-

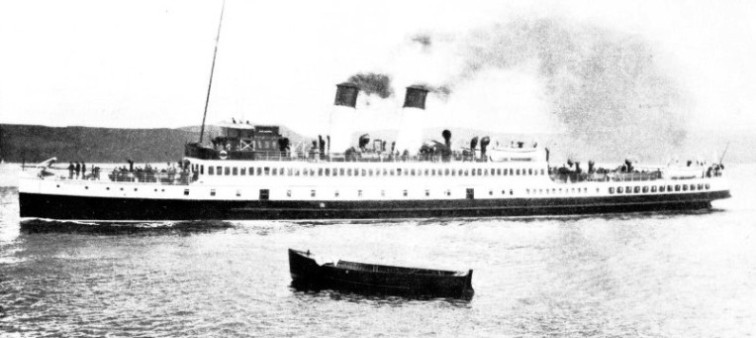

A TYPICAL CLYDE EXCURSION STEAMER, the King George V, a twin-

Thirteen years after the opening of the Kingston Dock, the first dock was opened on the right, or northern side of the river, at Stobcross. This is the famous Queen’s Dock, which begins at the western extremity of the Broomielaw, north of Cessnock across the river.

Queen’s Dock contains two basins, with an area of 33¾ acres, and 10,002 feet of quays.

At the time of the completion of Queen’s Dock, a start was made with the removal of Elderslie Rock, on the shores of the Clyde near Renfrew. The whole operation took six years, and was accomplished at a cost of some £40,000. Queen’s Dock and the improvements at Elderslie were followed by the opening of the Prince’s Dock at Cessnock, with three basins, on the left bank of the river. This has a water area of 35 acres and 11,212 feet of quays.

The Clyde is spanned by no bridges of any kind below the Central Railway Bridge at the east end of the Broomielaw, though it is crossed, as might be expected, by a number of ferries. In 1907, the 20J-

Altogether, there are 12 miles 180 yards of quay within the Port of Glasgow. Among these are Merklands Quay, where the landing of cattle is dealt with, and Meadowside Quay, devoted to grain handling and storage. At Meadowside Quay are the vast granary and elevators with a capacity of 31,000 tons of grain. Coal and minerals are dealt with in large quantities in the north quay of Queen’s Dock. Graving docks are situated at Govan, Partick and Elderslie, the largest being Govan No. 3, 880 feet long and 83 feet wide.

Extensive communications with the systems of land transport are essential on the Clyde, as at Liverpool, Southampton or any other great port. The London, Midland and Scottish Railway, incorporating the Caledonian and Glasgow and South Western Railways, has access to the harbour at Terminus Quay, near Kingston Dock. This line enjoys a monopoly of the left bank, as far as rail communication is concerned, though the great new arterial road of the Glasgow Corporation also has a convenient entry to the docks in the Renfrew neighbourhood. On the right bank of the river,

the docks are in communication with the L.M.S. (formerly Caledonian) and L.N.E. (formerly North British) Railways.

Some idea of the growth of Glasgow’s maritime trade will be gained from the following few figures. A century ago the trade was almost negligible. Port Glasgow had a little, but the lion’s share of what there was went to Greenock. In 1858, the year of the foundation of the Trust, the port handled 2,129,782 net register tons of shipping. In 1913, which was a peak year, the total net register tonnage dealt with was 13,461,059. In 1934 the figure was 11,114,018 tons.

The tourist who comes from the south or from overseas likes to think that the wildly beautiful Highland hills, the deep lochs and misty blue islands of the West Coast, and the broad, generous meadows and woods of the southern uplands form the face of Scotland. Perhaps he is right to think so, though, as his train or car passes through the industrialism of the Central Rift Valley, between Edinburgh and Glasgow, he usually tries to shut his eyes to passing impressions, as if to ignore an ugly scar on that same fair face. Yet it is the heart of that industrial area that is the heart of the country. Glasgow and her docks are the heart of Scotland. It is Glasgow’s shipping that has made her the city that she is.

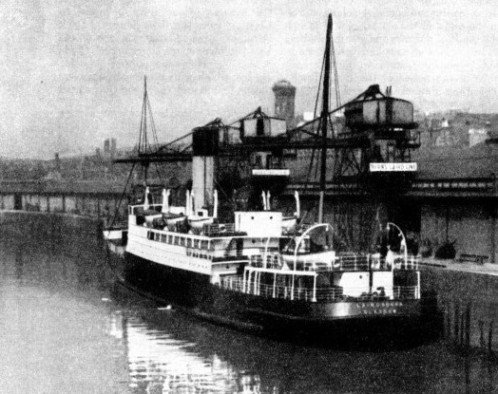

IN GLASGOW DOCKS there is generally a Burns & Laird Lines coaster loading or discharging. The Lairdsburn (left) was built as the Lady Louth in 1923. A vessel of 1,870 tons gross, she has a length of 276 ft. 7 in., a beam of 37 ft. 7 in.and a moulded depth of 16 ft. 8 in., with a corresponding draught of 15 feet.

The proper introduction to Glasgow is to enter the city by water. The Cloch Light is the real outpost of the port. The Cloch, with its tall white tower, is the last milestone to all who come to Glasgow by sea. Once the Cloch is passed, the traveller feels the atmosphere of Glasgow growing stronger with every beat of the ship’s screw. The mountains about the Firth of Clyde have been left behind. The chimneys, the smoke pall, the great cranes of the shipyards, are in front, with the Greenock yards as an advance guard. On the north bank of the river rise the hills above Craigendoran, on the south lies smoky Greenock, with its high buildings rising against a background of smoke haze and miniature mountain range.

The variety of the shipping encountered on this brown, slowly narrowing river is extraordinary. A red-

While we are still admiring her, there passes across our vision one of those ugly ducklings of a great river port, a dredger, with her big ladder down and her upcoming buckets clanking and splashing on their endless chain.

More and more of those dredgers, and their attendant hoppers, we see as we penetrate farther and farther up the Clyde. Their work never ceases. At Old Kilpatrick we are again among the shipyards, whose acquaintance we have already made at Greenock, Port Glasgow and Dumbarton, where ships’ unfinished hulls, and the poles and cranes of the yards compete for dominance with the bold outline of the Rock. But from Old Kilpatrick, we shall have the yards with us continuously all the way into Glasgow, and hereafter, also, the Clyde ceases to resemble a river at all. The Kilpatrick Hills rise bravely to the north, but between extends a forest of poles, huge cranes, halffinished ships of all imaginable sizes, and all the paraphernalia of a vast birthplace of innumerable vessels.

Here it is possible to see two ocean liners alongside, one all but ready for her maiden voyage, the other brought home after an adventurous existence to end her life under the oxy-

A Shipping Canyon

At Clydebank, where the little muddy River Cart runs into the main stream, we are at the birthplace of the Queen Mary, and of more than one of her great predecessors. Opposite John Brown’s yard is the narrow mouth of the Cart, flanked by green fields. An insignificant strip of water it seems, yet without it the great ship could never have been launched.

So we pass on towards the city, the closely packed shipyards sometimes alternating with pretty little stretches of residential property — clean grey villas rising among gardens and trees. There was never a more fascinating approach to a city than this. The river becomes more and more densely hedged in.

The Clyde is indeed no longer a river. It is not even a canal. Rather it is a narrow, shallow and nearly straight canyon, created for shipping and shipping alone. We have already passed the first frontiers of the docks. Govan, with its yards and ironworks, frowns at Partick across the river.

Our short voyage is nearly over now, for we are penetrating the heart of Glasgow, and a huge heart it is. Unlike London, Glasgow, with her 1,088,417 inhabitants, is not dominated by a wide suburban area, enormously swelling her population outside the bounds of the city. The entrance to the. Prince’s Dock is passed on the right, that of Queen’s Dock on the left. Tall masts and huge funnels of different colours, white ventilator cowls with dark red mouths appear grotesquely from behind walls of soot-

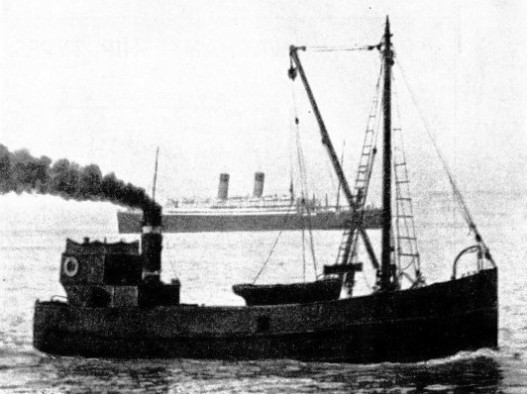

A CLYDE COAL GABBART of the type immortalized in Neil Munro’s stories of the S.S. Vital Spark. Gabbart is a Scottish word used to describe small craft of this type, which in the Clyde are often dwarfed by mighty ocean liners.

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this article.

You can read more on “The Caledonian Canal”, “Dredgers and Hoppers” and “Where the Queen Mary was Built” on this website.