© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

‘Twixt Highlands and Hebrides

On the West Coast of Scotland and in the Islands, where there are few railways and where roads are indifferent, transport depends almost entirely upon the sturdy packets which range from early paddle steamers to modern diesel-

STEAM DRIFTERS IN HIGHLAND LOCHS are a familiar sight. Fishing craft from the East Coast reach Hebridean waters after a voyage round the north of Scotland or through the Caledonian Canal. The drifters illustrated above come from Banff and are seen in Loch Inver, a sea loch on the west coast of Sutherland.

AT the beginning of the second century, the historian Tacitus said of the West of Scotland: “Nowhere is the power of the sea more extensive than here ... it works and winds its way far into the country, penetrating the rocks and mountains, as if these were its native bed”.

In many ways, Western Scotland has changed but little since the days when its wild sea lochs and mountainous coasts were explored by the Roman fleet. Even to-

The mountainous interiors of islands and mainland help to give the country its reputation of being one of the most beautiful regions in the world, but they limit the facilities of land transport to a minimum. Here is a place, rivalled in Europe perhaps only by Scandinavia, where the coastal steamship service comes into its own.

Though Highlands and Hebrides alike are not densely populated, they are by no means an empty desert of rock and water. Though the downfall of the Clans in 1746, and still more the notorious “Highland Clearances” of the last century, sent thousands of Highlanders southwards and overseas, there remains plenty of cargo and passenger transport to be dealt with by the well-

Since 1879 the David MacBrayne ships have carried the bulk of this indispensable yet often unremunerative traffic, sometimes in the most difficult and exacting conditions. The late David MacBrayne, one of the fathers of Clyde shipping, was a nephew of the Burns’s, who operated the West Highland steamers before 1851, when the fleet was taken over by David Hutcheson and Company. MacBrayne became one of the partners in the Hutcheson Company, which operated the fleet until he acquired it and thus brought it back into his own family.

Until 1905, David MacBrayne operated efficiently and autocratically. Its name became a household word on the Clyde, on the West Coast and in the uttermost parts of the remote Outer Hebrides. Then David Hope MacBrayne succeeded his father and the company in 1906 was reconstituted as David MacBrayne Limited. The original David MacBrayne, who had done so much to reopen communications in the West Highlands, survived his office by one year, and died in 1907 at the age of ninety-

The mail contract with the firm expired in 1928, and with its renewal came the close of another epoch in the history of the line. Trade all over the world was beginning to slide rapidly into the depression which reached its climax in 1931-

It is doubtful whether any firm in the shipping world has as wide a variety of activities within a relatively small area as the present MacBrayne company. On the Clyde, and to a considerable extent in the West Highlands, there is a heavy summer seasonal holiday traffic, in many ways resembling that of the ea-

Glasgow, with more than a million inhabitants, though in some ways one of the grimmest of the great European cities, is but a little way from a coastal district of unrivalled beauty. When the Glaswegian goes “doun the watter”, he is transported in a short time into a sublime fairyland where the ocean itself invades the mountains, in the way which the Roman historian found so astonishing.

For those who can give more time to their excursion, a tour lasting several days can be made from Glasgow into the heart of the Highland fjords. It is possible to travel to Oban by two routes; either direct by a special motor coach, or by steamer to Ardrishaig and then on by motor-

Island of Basalt Pillars

To the south-

At the foot of Loch Linnhe, too, there is another link with the days of long ago, namely Dunstaffnage Castle, near Oban. Though the present castle is relatively young (a ruin dating from the Middle Ages), Dunstaffnage was once the administrative capital of the Scottish kingdom, and more than one ancient king went forth from it to do battle with the Romans in the south.

Having skirted the island of Lismore, the steamer runs parallel to the district of Appin, immortalized in R. L. Stevenson’s Kidnapped. Thereafter comes Ballachulish, at the foot of lovely Loch Leven and overshadowed by the perfect pyramidal mountain called the Pap of Glencoe. The whole district, as well as being superbly beautiful, is full of historical associations. After Ballachulish, the loch narrows into what might be likened to a straight, grimly mountainous passage for the sea. At the head of this strait lies Fort William, crouching under the bare, rocky wing of Ben Nevis.

From Fort William a traveller may return to Glasgow by the scenic West Highland Railway, or continue to Inverness by the steamer Gondolier, which plies on the Caledonian Canal. Or, again, he may take the train through the wild mountains of western Inverness-

THE FAMOUS TWO-

This combined land and water trip to Skye is perhaps the finest of all the famous Highland tours. There are others, however, almost as attractive, such as that from Oban to Staffa, the island of basalt pillars and marvellous caves, and to the quiet island of Iona, the birthplace of Scottish Christianity and the burial place of the ancient kings. All this is romantic, but important as the summer tourist traffic may be, there is another, sterner side to the company’s activities, though perhaps less remunerative than the tourist trips. The islands of the Inner and Outer Hebrides, great and small, are for the most part sparsely populated. The same applies to the indented coast of the mainland north of the Kyle of Lochalsh, the farthest point reached by the railway. But communications must be maintained between all of them. The mail steamer must turn out of her direct course to visit some tiny island, a single mountain rising out of the Western Sea. And there, perhaps, she drops and picks up mail bags, puts ashore a few supplies and takes on board perhaps a crofter’s son destined for Glasgow University. It is little enough traffic, but such calls as these have to be maintained throughout the islands.

In summer and in winter the stout little steamers of the Hebridean fleet face the Atlantic rollers and the turbulent grey waters of the treacherous Minch, on the run from Portree in Skye to Stornoway in Lewis. These ships provide the sole means of communication between Stornoway, that remote little metropolis, and the rest of the world, and without fail one of these tough, red-

The distance between Stornoway and Glasgow is nearly 200 miles. This is no mere channel crossing for a brave little ship of less than 1,000 tons. Calls at Stornoway, however, do not suffice for the Outer Hebrides. There is Loch-

Deserted St. Kilda

Farther inland and farther south, the islands of Rum, Eigg, Coll, Tiree, Mull, Islay and Jura, to mention only a few, are all dependent on the stout little fleet for their communication with the outside world. Even on the Isle of Skye, which has a motor ferry connecting it with the railway terminus at Kyle of Lochalsh, people talk of “going over to Scotland”, as if they were going to some foreign country.

Until a few years ago, a service to a destination even more remote than the smaller islands in the Outer Hebrides was operated during the summer months.

This service was in the hands of McCallum Orme and Company. The firm’s two steamers, the Dunara Castle (457 tons) and the Hebrides (585 tons), used to form the connecting link between Scotland and the isolated rocky island of St. Kilda, forty miles out in the Atlantic.

St. Kilda is a bare, isolated mountainous rock rising from the sea. Even before it was evacuated in 1930, St. Kilda had fewer than a hundred inhabitants who lived in primitive stone houses with earthen floors and spoke an archaic kind of Gaelic, just as their forbears had done more than a thousand years before.

When the Dunara Castle had made her last call at the end of the season, the St. Kildans were shut off from the outside world until the following spring. The chance call of a passing whaler would be the only event to remind them that they were not alone in the world. To-

A TWIN-

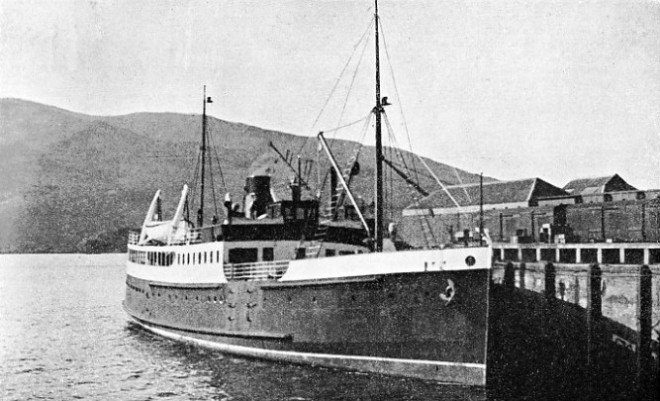

A fine example of the steamers in the Hebridean service is the Lochness. The third vessel of that name, she was built in 1929 by Harland and Wolff at their Glasgow yards. She maintains the Stornoway mail service. Her gross tonnage is 777; she is 200 ft. 4 in long, 34 feet in beam and 101 feet deep. She is driven by twin screws and her propelling machinery, by Kincaid of Greenock (Renfrewshire), consists of two sets of three-

She is of handsome proportions, which are enhanced by her black hull, white upper works and large red funnel with a black top. This is the regular colour scheme of the majority of the MacBrayne steamers, though buff funnels and grey hulls have appeared now and then. The house-

During the annual overhaul of the Lochness in dry dock, her place is taken by the Lochmor, a twin-

During the summer season, seven-

Veteran Paddle Steamers

Of the most recent vessels, the twin-

As a contrast to these fine modern vessels, three famous old steamers were included in the MacBrayne fleet until recently. The veteran was the paddle steamer Glencoe, which was built as far back as 1846. She survived on the exacting Mallaig-

Originally named the Mary Jane, the old Glencoe had an iron hull. Her paddle wheels were driven by an ancient steeple engine with a single cylinder 56 in. by 54 in. This engine was saved from the breakers, and may be seen at the Glasgow Art Gallery. Her gross tonnage was 226. She was acquired for the Hutcheson fleet in 1857 from Sir James Matheson of Stornoway. In 1934 the twin-

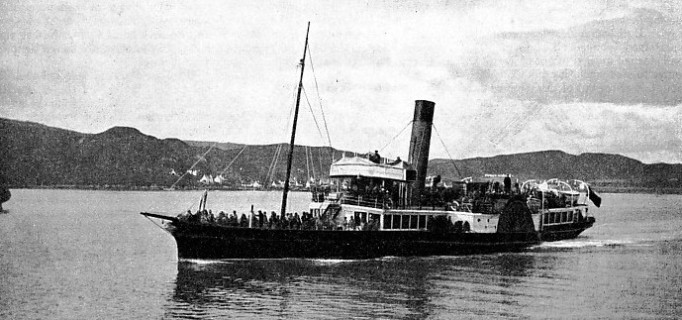

The famous two-

The Columba, which also lasted until 1935, was probably the most famous paddle steamer on all the British coasts. When she first appeared, no similar vessel had been seen on the Clyde, and her beautiful proportions and the Victorian gorgeousness of her saloons brought her fame and popularity. She had a gross tonnage of 602. The Iona and Columba were replaced by the turbine steamers Saint Columba and King George V (789 tons gross).

The fine old paddlers, in their dress of black and white with red funnels and ornate gilded scrollwork on their ample paddle-

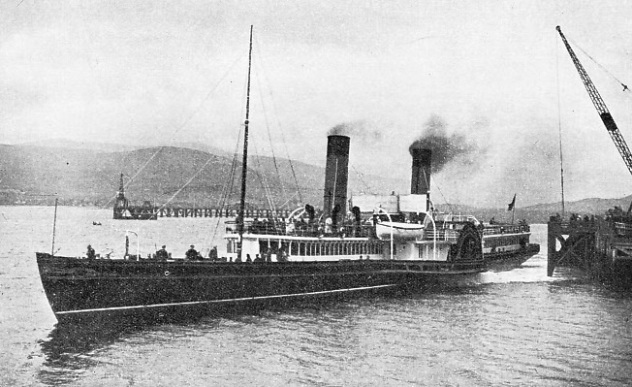

IN THE KYLE OF LOCHALSH many services connect the railway terminus at Mallaig with various islands of the Hebrides Shown here is the Fusilier, a fine paddle steamer built in 1888 and sold in 1934. She had a length of 202 feet, a beam of 21 ft. 7 in., a depth of 8 ft. 1 in. and a gross tonnage of 280. The Fusilier attained a speed of 14 knots.

You can read more on “The Caledonian Canal”, “Coastal Pleasure Steamers” and

“Thames Butterfly Boats” on this website.