© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Holland’s Inland Ports

The cities of Amsterdam and Rotterdam are not only unusual and picturesque, but they are also vital centres of a great maritime nation and among the most active ports in Europe

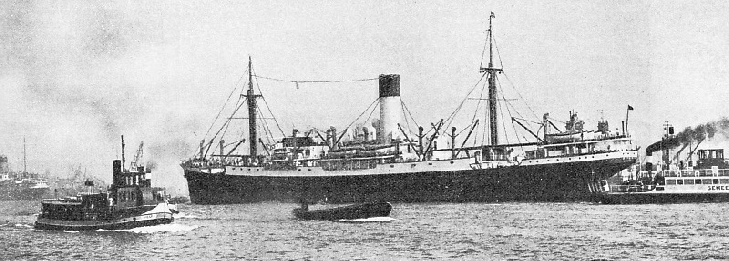

AT AMSTERDAM. A busy scene on the River Ij. The port is linked with the sea on one side by the North Sea Canal, and on the other side by the canal locks to artificial channels in what was formerly the Zuider Zee. The North Sea Canal is capable of taking the largest ships likely to use it and is at present 246 feet wide with a depth of 41 feet. The above photograph shows in the centre the Myrmidon, a twin-

RHINE barges, river paddle tugs, sea-

The rival of Amsterdam, in the eyes of most Dutchmen, is Rotterdam. This inland port is equally picturesque, and it too is connected with the North Sea by a canal, the New Waterway. The New Waterway has no locks. Rotterdam resembles Amsterdam in the profusion of its ship types, but it has many more river ships, since it has direct contact with the countries of Europe by canal and is a transhipment port. It has also more shipyards than Amsterdam, though it is difficult to say which port builds the better vessels. Rotterdam is a city of noise and bustle. There is little or nothing medieval about it.

Amsterdam cannot be visited without giving the impression of quiet dignity. This impression is heightened by the vistas of old canals, the Dam and the Heerengracht -

From the de Ruyterkade (de Ruyter Quay), facing the station, little piers jut out at right angles to the water-

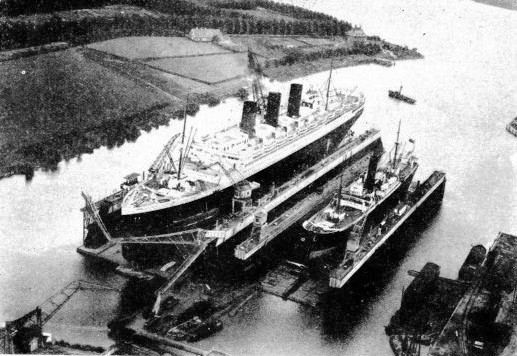

IN DRY DOCK at Rotterdam. A splendid view of the famous French transatlantic liner Paris. This vessel was built in 1921 at St. Nazaire. She has a gross tonnage of 34,569, a length of 735 ft. 5 in., a beam of 85 ft, 3 in. and a depth of 59 feet-

The North Sea Canal runs through flat country and its course is interrupted only once -

In this connexion reference must be made to the lock at Ijmuiden, one of the largest sea locks in the world. It has been completed with every attention to modern architectural details, a feature in which Dutch architects excel not only at their maritime work but also on shore. Incidentally, it is worth recalling here that the building in Amsterdam known as the Scheepvaarthuis, which houses the offices of all the principal steamship companies and overlooks the port, has been built on a corner site in the semblance of the bows of a ship. Similarly the control houses for the canal locks are circular and resemble the conning tower of a modern warship.

This magnificent entrance lock to the North Sea Canal is 1,312 feet in length, 164 feet wide and 49 feet deep. The situation is one of the most exposed in European harbours. If a traveller is waiting to board a ship at the lock on a windy day it is possible for him to lean against the wind, and it is no uncommon event for a ship moored near the entrance to require about an hour to be pulled alongside if the wind is against her, and the sea outside is correspondingly ruffled.

The canal is well maintained and wide enough for two of the largest vessels at present using the port to pass. Such a procedure does not generally occur, as there is not much room to spare. On one occasion, however, a new liner, crack ship of the East Indies trade, outward-

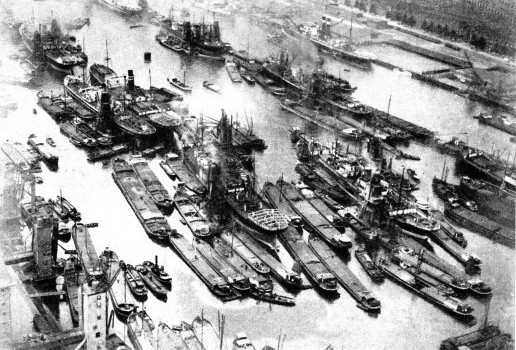

BUSY ROTTERDAM. A photograph of the port, showing many of the Rhine barges which are a particular feature of the waterways near the city. The River Maas, which flows past Rotterdam, is an effluent of the Rhine, which connects Switzerland with the North Sea. Rotterdam’s principal link with the sea is the New Waterway, entered at the Hook of Holland.

Amsterdam is an easy port to visit, because of the numerous little ferries running from the de Ruyterkade to various points in the harbour. Each of these local services has a number, being known as Ijveer I, II or III, according to its destination. By them most of the points of interest can be visited. For Amsterdam is a simple harbour in that, the water portion comprises the River Ij, running “fore and aft”, merging with the North Sea Canal at one end and broadening into a species of lake at the other, useful in times of depression for laying up ships.

Facing the de Ruyterkade are the entrance locks to the North Holland Canal, and an unloading depot for oil and petrol. The main petroleum dock, situated farther down the river, has a total capacity of about 100,000 tons. Oil and general cargoes are not the only reasons for the importance of Amsterdam as a port, for among the largest importers of timber in Europe it ranks after London. Transit traffic is an equally important feature. Much freight is transported to and from the Rhine and its basin.

Amsterdam is also a transhipment port for goods from South Africa consigned to Mediterranean ports, for colonial products destined for England and Northern Europe, and for West African products sold to London, America and Mediterranean ports.

As transhipment is one of the outstanding features of the port, it is not surprising for the visitor to find that there is a forest of cranes almost everywhere he turns. One steamship company has over seventy at its disposal, and the port has an aggregate of over 300 cranes able to lift all sorts of cargo from one and a half tons’ to eight tons’ weight. In addition, little tugs may be seen, pulling floating cranes on square box-

Great warehouses flank the quay. Some of the sheds of the companies trading to the tropics have specially heated rooms for storing sub-

Pneumatic Elevators

Numerous warehouses are situated in the harbour and along the many canals of the town, in which are stored valuable cargoes such as coffee, tea, tobacco, copra, cinchona bark, rubber hides, kapok and the like, which are brought to the Amsterdam market.

Large refrigerating stores are built alongside deep water for the frozen meat which comes from South America; other big sheds carry rubber from the Indies. Grain, too, is a cargo which can be seen at any time being drawn from the holds of ocean-

So rapidly is this cargo dealt with that the spectator can almost see the ship rising out of the water. It is no uncommon sight to see such a vessel trimming heavily by the bow or by the stern. The unloading is accompanied by the hum of the centrifugal pump that deals with grain. A film of dust hangs over the operation. Other bulk cargoes such as coal, ore and minerals are worked efficiently and economically by floating grab cranes, coal tips, electric transporter bridges and other loading and discharging equipment.

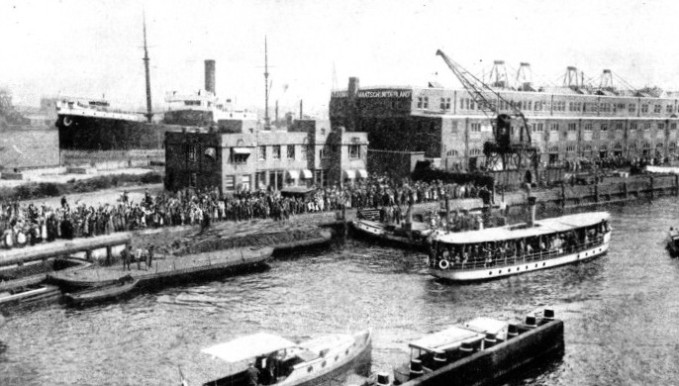

ADMIRING CROWDS THRONG THE BANKS at Amsterdam as an East Indies liner -

Floating equipment is a feature of all northern European ports and adds to the variety of craft that make up the picturesqueness of Dutch waterways. Many of the most important Dutch steamship companies use Amsterdam as their terminal. Important lines of other nationalities such as the Hamburg-

Rotterdam is a centre of intense activity. A visitor, standing on the Maas Bridge, a magnificent steel and concrete structure, may obtain a wonderful panoramic view of the life of the port. Battling upstream is a sturdy river paddle-

Astern of this are four or five huge barges, probably of 1,000-

At the after end are the windows and the brown painted structure of a little cabin, the outside of which may be gay with flowers and festooned with washing. For the Rhine barge, as she is called, is not only a cargo vessel; she is also the home of the barge captain, his wife, his family, and sometimes of his relatives. They spend most of their interesting, colourful and changeful lives in this little craft. A week after the Rhine barges have left Rotterdam they may be unloading iron ore in the grimy Ruhr district of Germany. Then they may proceed almost to the Swiss frontier to pick up another cargo, which by river and canal may take them to places as far distant as Hamburg or Rouen.

Famous Ship-

The Rhine barge is a familiar sight in the port of Rotterdam, more so than in Amsterdam. For in Rotterdam, near the airport, situated close to the water, is a big lying-

Farther down the river are the big shipyards and repair shops. Rotterdam is one of the most famous ship-

There are many entrances and exits between Rotterdam and the North Sea, some of them winding through sand dunes, all of them through flat country. Rotterdam’s principal gateway is the New Waterway, an artificial cut open to the sea, slightly longer than the North Sea Canal, the entrance to Amsterdam. It is wide enough for several ships to pass at a time. On its sides are coaling depots, oil bunkering stations and, finally, the port of Vlaardingen. This little port is the home of the world’s most famous fleet of salvage tugs. From Vlaardingen go big ships which tow floating docks from the Tyne to New Zealand, or rescue damaged vessels in mid-

VIEW TAKEN FROM AN AEROPLANE flying over Amsterdam. The port handles oil, timber, grain and general cargo of almost every description. It is a big transhipment port for goods from South Africa consigned to Mediterranean ports, and for Dutch Colonial products destined for the markets of Northern Europe.

At the entrance to the New Waterway is the Hook of Holland. This well-

Let us emphasize again that there is much of the practical and little of the historic in Rotterdam, although in the many basins which flank the New Waterway and in some quarters of the town there are signs of a historic past. Thus, not far from the Maas Railway Station is the quiet Wijnhaven, now flanked mainly by dignified office buildings. This is used merely by the smallest of local craft. The Railway Harbour (a small ship harbour), the Rhine Harbour and the Park Harbour are all other backwaters of Rotterdam, whose names are significant in themselves. There are also the Salmon Harbour and a small waterway called by the name of Haringvliet.

In the centre of Rotterdam the Maas is split in two by an island site containing quays and warehouses. Ships tie up alongside here or anchor to dolphins in the river. This island site is connected to the mainland by bridges on either side, one of which is the Maas Bridge mentioned above. There are also two railway bridges taking a through line from Rotterdam and Amsterdam to Rosendaal and the Belgian frontier. Rotterdam, similarly to Amsterdam, is a city of bridges, no less than a city of cyclists. Appointments with shipping friends must be made with an ample margin of safety, for the visitor may be held up perhaps for twenty minutes while a group of ships and tugs passes by.

By taking proper advantage of high tide, ships whose draught is as much as 33 feet can reach the port of Rotterdam with unbroken cargoes and still have a depth of 1½ feet of water beneath their keels. In the harbour of Rotterdam and the neighbouring harbour of Schiedam there are sixteen dry docks, some of which will lift vessels up to 46,000 tons.

There are a number of harbours in the port of Rotterdam, some of considerable size. Parkhaven, for instance, is about 1,470 feet long and 393 feet wide. It has a depth of 21 feet and the length of quayage is 2,940 feet. Parkhaven is connected by locks with a number of inland canals.

The longest quays in Rotterdam are situated on the right bank of the river. Boompjeskade is a quay 3,090 feet long. There are 28 feet depth of water alongside Lloydkade, a quay 1,740 feet in length. In the river itself mooring buoys afford accommodation for seventeen large seagoing vessels, and there is ample space for smaller vessels such as lighters or barges. In Maashaven, a harbour on the left bank with a water area of 148 acres, there is a steel floating dock with a lifting capacity of 15,000 tons.

Most of the harbour craft in Rotterdam, as in Amsterdam, are self-

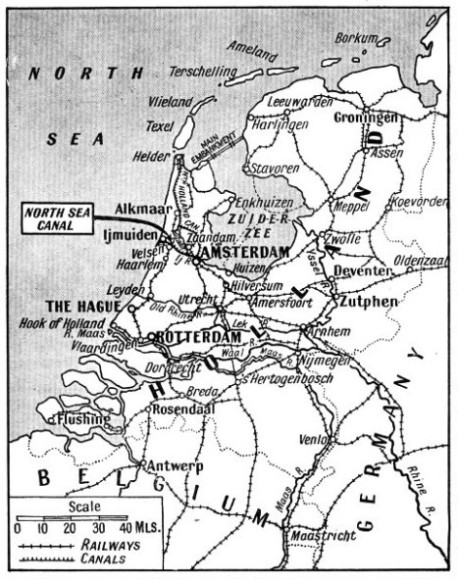

AMSTERDAM AND ROTTERDAM are the most important ports in Holland. Amsterdam is an inland port that has no natural outlet to the open sea. Ships bound for Amsterdam enter the North Sea Canal at ijmuiden and after sixteen miles arrive at the great port. Another canal, known as the New Waterway, connects Rotterdam with the sea.

You can read more on “Dutch East Indies Inter-

“The Statendam” on this website.

You can read more on “Reclaiming the Zuider Zee” in Wonders of World Engineering