© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Development of the Oil Tanker

Oil and spirit in bulk form the most dangerous cargo that ships have ever carried. Many special constructional devices have been evolved to obviate, as far as possible, the risks entailed by this perilous cargo

ROMANCE OF THE TRADE ROUTES -

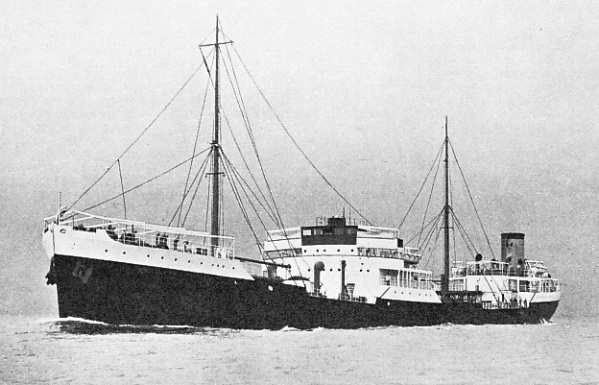

A MODERN TANKER built for the Anglo-

A long, low-

Although these tankers are trim, clean ships, they are the hardest-

A trip from the Antarctic with whale oil to Rotterdam, for example, may be followed by a transatlantic run, prolonged through the Panama Canal to Los Angeles. The tanker’s crew is well paid and the conditions are good, apart from the orders against smoking and the ever-

According to the returns of Lloyd’s Register of Shipping, the total tonnage of oil tanker vessels increased from just over 1,478,988 gross tons in 1914 to over 9,000,000 gross tons in 1935. This development has been parallel to the increase in the use of oil for all domestic, industrial and marine purposes.

Such a development shows the importance of the oil-

Crude oil, a thick oil straight from the wells, has the consistency of treacle in cold weather. On the coldest of days it is so solid that it has sometimes been necessary to dig it out of the tanks. In the shipment of crude oil, expansion and contraction with changes in climate must be allowed for. It is also necessary to fit heating coils to keep the crude oil’s viscosity or “thickness” under control as far as possible.

Lubricating oil is familiar to all car owners who buy oil of this type in sealed bottles. This oil is brought across the sea in tankers which may carry as many as twenty-

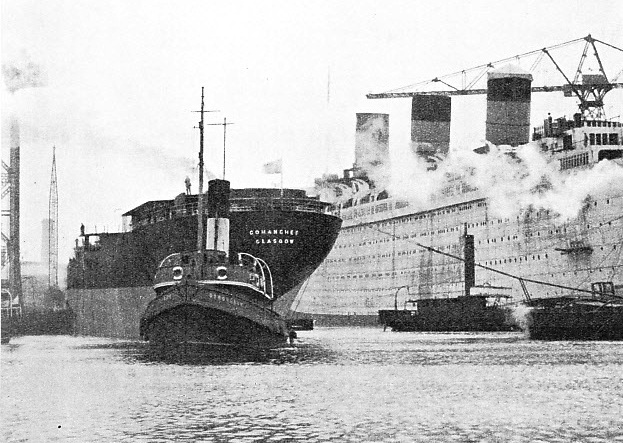

IN THE FITTING.OUT BASIN on the River Clyde where the Queen Mary was completed, special care had to be taken to prevent the newly-

Gasoline, petrol, or the other highly volatile derivatives of crude oil comprise the most difficult and dangerous cargoes of all. They are explosive, and a fire in a petrol-

Casinghead gasoline wears out a ship’s hull in less than half her normal life of about twenty years. It is partly for this reason that about forty tankers, with a combined gross tonage of about 300,000, are under construction every quarter in the year. The tanker owner has tried to overcome this wastage in another way. In some instances he has scrapped the centre or tank portion of the ship, retained the stern with its machinery and the bow with its small dry-

At least one fine fleet of tankers is sometimes employed to transport molasses, or sugar syrup, from ports in the East Indies or in Cuba to industrial centres in Europe and the United States. Molasses is similar to thick crude oil and in construction molasses carriers and oil tankers are identical.

There are many uses for tankers today. So fastidious has the modern motorist become that many ingredients are added to his petrol to give him a few more miles to the gallon. Some of these ingredients are gaseous in nature. They are carried under pressure in vertical cylinders. This cargo is difficult to manage, for if anything goes wrong with the pressure, the ship arrives in her home port without her cargo.

A modern tanker’s hull is cellular in construction, and her machinery is aft. Between one or two pairs of divisions or bulkheads are situated powerful pumps. These send the liquid cargo along continuous fore-

If only one type of oil cargo were to be carried, the simplest form of tanker would be a decked-

The obvious procedure, therefore, is to split up the free surface of the liquid. This is best done by arranging fore-

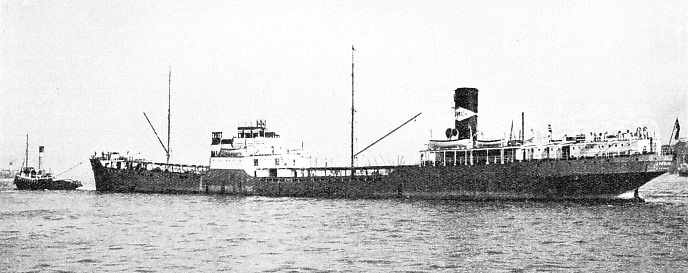

VARIOUS TYPES OF CARGO may be carried in modern tankers. Sugar syrup, or molasses, is brought to consuming countries from the East Indies and Cuba in tankers. The Athelknight, 8,940 tons gross, was built in 1930 for the United Molasses Co, Ltd. She is 475 feet in length; her machinery is placed aft and her officers’ accommodation amidships, as is usual in tankers.

Tanker design has been evolved on the assumption that crude oil is to be carried. We have seen that crude oil varies in volume according to the temperature. Hence, above every main tank and all fore-

The regulations affecting tankers are strict, and do not always make for the comfort of officers and men on board. Most harbour authorities will not allow oil depots within several miles of their ordinary quays. Thameshaven, for instance, on the Essex shore of the Thames estuary, is one of the spirit depots of London. Saltend Jetty on the River Humber is some distance from the port of Hull. No light or power is allowed on a ship discharging gasoline, and for twenty-

The narrow expansion tank built up along the top of the main tanks has suggested to naval architects the possibility of using the space between the expansion trunk top and the ship’s side. This space can be made into another tank. A tank so arranged is known as a summertank. In modern tankers this is not now used universally, although it may fulfil an important function for carrying special oils.

Far Eastern Origin

The machinery of a tanker is aft for two reasons. Machinery amidships would break up the tank space by the presence of the tunnel in which the propeller shaft works and this would also duplicate the expensive pumping machinery. In addition, the farther aft of and away from the oil cargo the machinery is, the less the risk of fire. All kinds of machinery are employed for propulsion -

Welding is playing an increasingly important part in tanker construction because it permits strong joints to be made easily in portions of the ship’s structure that are rather inaccessible to riveters and caulkers. It may be that the all-

We have spoken of the evolution of the bulk liquid carrier. For the earliest information we can go back to Chinese history. There are records of a Newchwang junk specially caulked and fitted with internal divisions to carry water in bulk.

Originally built at the beginning of the eighteenth century, these junks were later used for petroleum. They had a capacity of about fifty tons.

The cross-

Petroleum was carried also dowTn the River Irrawaddy from the hand-

Early in 1795 a Mr. Gibson of the Isle of Man had the Ramsey, an iron sailing tank vessel, built to carry oil. The cargo space was divided into compartments by a centre line and several ’thwartship bulkheads. Since they were completely filled and were air-

These vessels were provided with transverse and central longitudinal bulkheads; expansion was controlled by the fore and main masts, which were of hollow iron construction. The ships were evidently the first to carry their own pumps.

The Atlantic was wrecked after about six years, but the Great Western operated until 1896, when she was abandoned at sea.

The Charles was a later ship fitted with iron tanks for oil carriage. The tanks were built to fit the interior moulding of the ship, and were worked on the separate tank system without pipe connexions. Her total capacity was 794 tons. She operated from 1869 to 1872, carrying crude oil from the USA to European ports. She was destroyed by fire in 1872.

Russia was one of the earliest commercial sources of oil, and much money was spent by the Nobel Brothers in developing suitable craft to carry crude oil on the River Volga and on the Caspian Sea. Oil in barrels, known as case oil, was early in the present century carried in sailing ships, some of them specially adapted.

The history of sailing oil-

One man who has perhaps done more than anyone else to bring the tanker to its present state of perfection is Sir Joseph W. Isherwood. He patented the Isherwood longitudinal system of framing, to be applied to all ships, but in particular to tankers. Although this system was followed by a number of modifications, it is to-

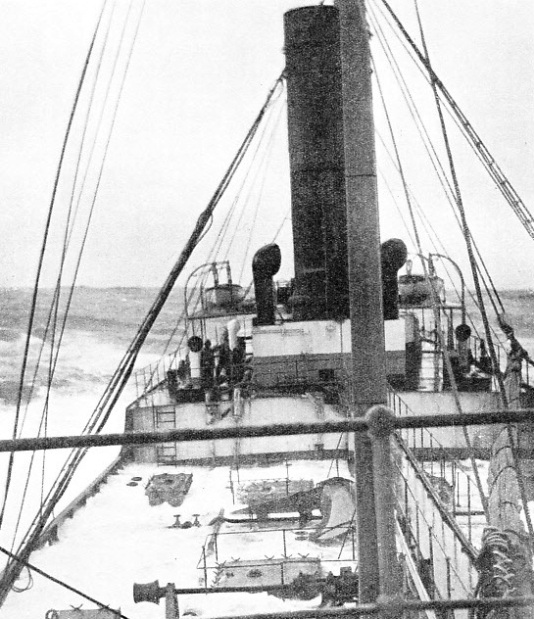

THE SEAS RECEDING from the low amidships deck of the oil-

As the oil cargo rested directly upon the skin of the ship, Isherwood realized that a tanker needed longitudinal strength above all other constructional attributes. The ordinary ship has narrowly spaced transverse frames and widely separated longitudinal girders. The Isherwood vessel has widely spaced deep vertical structures or “ frames ” between the numerous tank bulkheads, and also narrowly spaced longitudinal girders, whose scantling or size is no greater than that of the normal transverse frames. A ship thus built is able to withstand enormous shear forces -

There are hundreds ot tankers busy on the Seven Seas of the world. Most of them are either big vessels carrying from 10,000 to 12,000 tons, or small coaster types carrying 1,000 tons down to about 250 tons. The big ships are owned by the major oil companies, such as the Anglo-

A typical large tanker has a deadweight tonnage of 17,650 and a gross tonnage of 12,097. Her dimensions are 521 feet long between perpendiculars, a beam of 70 ft 3 in and a depth of 38 ft 9 in. She draws when fully laden 30 ft 6 in, and her speed of 11½ knots maximum requires two screws with a total of 4,700 brake horse-

You can read more on “The Comanchee”, “Progress of the Motorship” and “Refrigerated Ships” on this website.