© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Dutch Shipping

For long the Dutch were the keenest rivals of Great Britain in maritime interests, particularly when the trade routes to the East were being opened up. Their shrewdness and commercial sense have won the Dutch an important position in world shipping

SEA TRANSPORT OF THE NATIONS -

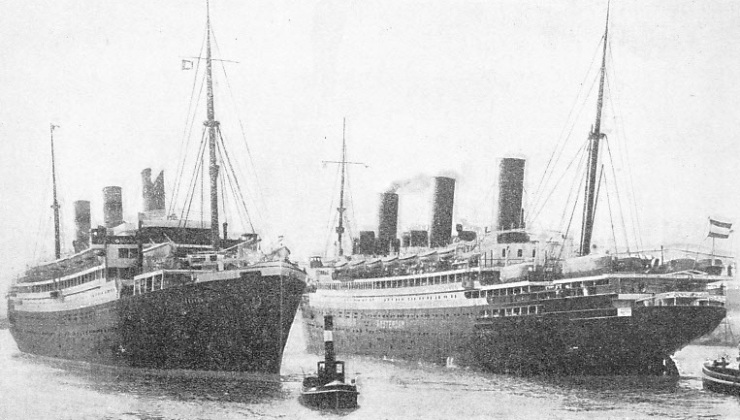

UNDER THE DUTCH FLAG these vessels were known as the Brabantia (left) and the Limburgia (right). The Brabantia was built at Bremen in 1920 as the William O'Swald, and after some years service was sold to the Hamburg-

THE Dutch have been one of the premier maritime peoples in the world for many years past, largely because they devote themselves heart and soul to their business. They have proved themselves to be doughty fighters on many occasions when their business has been threatened, but normally they desire only to be left alone to their trade.

It was other people’s anxiety to fight which gave the Dutch their first chance, for when England was distracted by the beginning of the Hundred Years’ War and all her commercial work was put aside, the Flanders merchants saw their opportunity. Not only did they expand their own trade, but they also invited the Mediterranean traders, especially those of Venice to bring them Eastern products. Before long they had made their ships far more practical carriers than the Italian galleys and they gradually got the transport business into their own hands. Their cities were the great centres of distribution. The absorption of the Netherlands by Spain in the fifteenth century was, for a time, greatly to the advantage of Dutch shipowners; but times changed, and during the struggle for independence the Dutch suffered much, although shipping became more and more essential to their existence.

LEAVING SOUTHAMPTON DOCKS is the famous Nederland liner Johan van Oldenbarnevelt. She is a twin-

The Wars of Independence bred a magnificent type of seaman who learned his craft among “the Beggars of the Sea” and such organizations. Men of that type were ideal for the ventures of explorers such as Willem Barents, Linschoten and Lemaire, and for the early trading ventures where every merchant had to be prepared to fight for what he had secured, or occasionally for what his rival had secured before him. The Dutch opened trading communications with the East at the end of the sixteenth, and with the West at the beginning of the seventeenth century.

In 1595. before the British East India Company had been founded, a Dutch expedition of four ships under Cornells Houtman rounded the Cape of Good Hope and in the course of a two-

The English proved more dangerous rivals, for the ships of the East India companies were equipped for fighting, and English aims were precisely the same as those of the Dutch. Many efforts were made to drive them out of Eastern waters, but although the expeditions of the Dutch East India Company were generally bigger than those of the British (the first in 1602 consisted of thirteen ships), there was plenty of trade for all and the fighting was unnecessary.

The enterprising Dutchmen made a flourishing trade settlement in Japan and kept their position for many years by interesting themselves in trade only. They cleared the Portuguese out of Ceylon and formed trading settlements in the West Indies and South America In the East Indian islands they were supreme. After a little experience the English company decided to concentrate on the mainland, and the Dutch monopolized their trade in spices, cloves, nutmegs and the like. They were not so lucky in China, where they got roughly handled, but there was plenty of trade elsewhere to keep all their markets busy. Their merchant service expanded rapidly, principally for the trade in their own colonies.

A HOLLAND-

A HOLLAND-

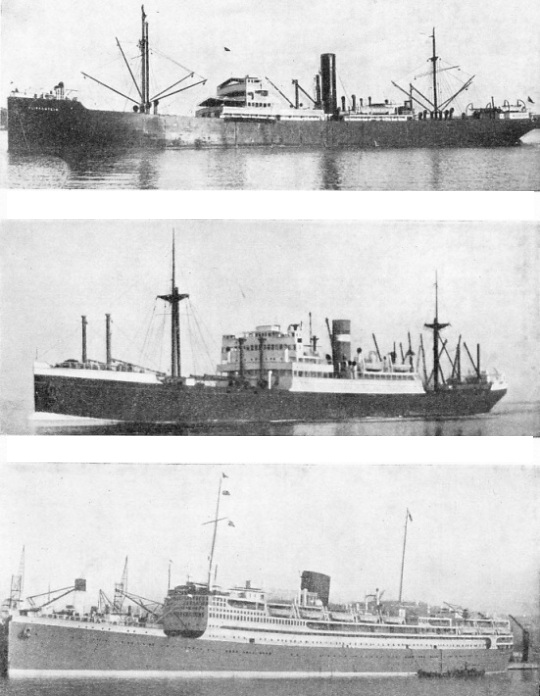

BUILT AT GREENOCK in 1923, the Drechtdijk is a twin-

ONE OF THE FINEST ROTTERDAM LLOYD LINERS is the Dempo, a twin-

On the prosperity of their shipping, founded on their own Colonial trade, the Dutch later built up a big carrying business, and by the efficiency of their methods they soon became the principal carrying nation in the world. Every flag which had no mercantile marine of its own turned to the Dutch for transport, and in the middle of the seventeenth century they bade fair to capture a big proportion of Great Britain’s commerce.

Cromwell hit directly at this carrying trade by reviving the medieval Navigation Acts and making them effective. Faced with the ruin of the business, the Dutch fought magnificently, and during the Commonwealth and the reign of Charles II the two sea powers were remarkably evenly matched. Holland had the advantage of the corruption of the British administration and Great Britain had the advantage of the bitterness of Dutch politics. Mutual self-

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, however, Dutch shipping began to go ahead again. A number of the companies owning ships or connected with shipping to-

This was largely due to the enterprise of their people, and they were the first European shipowners to send a steamer across the Atlantic. She was a little vessel of 438 tons, built at Dover in 1826 as the Calpe and intended for the short sea trades. As soon as she was completed the Dutch Navy bought her, renamed her Curacao and used her to carry passengers, mails and special cargo between Holland and the West Indian colony of Curacao. She was the first steamer to cross the Atlantic in a westerly direction.

Free Trade in Shipping

The Dutch are proverbially stubborn, and in the shipping business they flatly refused to be discouraged by repeated failures. They clung to the reservation of the trade between the homeland and the East Indian colonies after British shipping had declared for the freedom of the seas by repealing the Navigation Acts, but they saw how it was handicapping their business and as soon as they were convinced they followed the British example. Ever since then the Dutch have been the principal advocates of free trade in shipping.

About 1840 they attempted to run a regular steam Atlantic service, but this was a failure and it was not until 1871 that the Holland-

Other companies followed and won an excellent reputation for the cleanliness and regularity of their passenger ships and for the efficiency of their cargo side. The result was a great increase in their business, although they always kept the economic purpose of their ships in mind and seldom built to any extreme size or speed.

During the war of 1914-

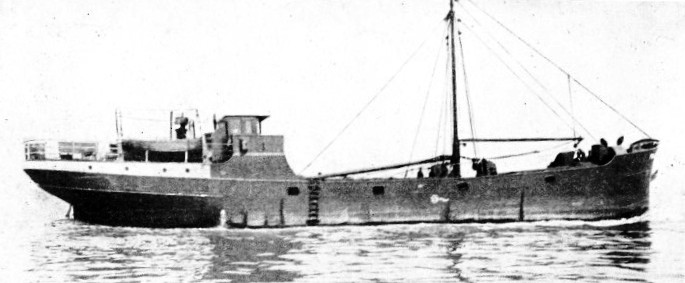

A REPRESENTATIVE DUTCH MOTOR COASTER of 250 tons gross. Built at Hasselt, on the Zuider Zee, in 1931 the Pollux is registered at Delfzijl, on the estuary of the River Ems. The Pollux has a length of 121 ft. 7 in., a beam of 23 ft. 7 in. and a depth of 7 ft. 10 in. The shallow draught of such vessels makes them most suitable for trade on inland waterways and to many of the lesser British ports, where they are frequently seen.

On the other hand, the Allies demanded the use of a number of Dutch ships for war purposes in return for bunker coal. The Germans sank these ships with their submarines just as they did those of any other country, although Germany was largely dependent on Holland for such contraband as contrived to slip through the British blockade. A good deal of tonnage had to be requisitioned by the Dutch Government to maintain the country’s grain supplies, and many of the passenger services had to be suspended owing to the risk to life. In spite of it all, Dutch shipping prospered as it never had before, and a considerable proportion of the excess profit earned was carefully laid aside to build new ships as soon as the opportunity arose. At the present time the Dutch mercantile marine is one of the most efficient in the world. On the North Atlantic the Holland-

The 24,149-

Between Holland and the Dutch East Indies the big trade is virtually monopolized by the two biggest companies under the Dutch flag, the Rotterdam Lloyd and the Nederland Line. They maintain regular services with exceptionally comfortable passenger liners and some of the finest cargo motorships afloat.

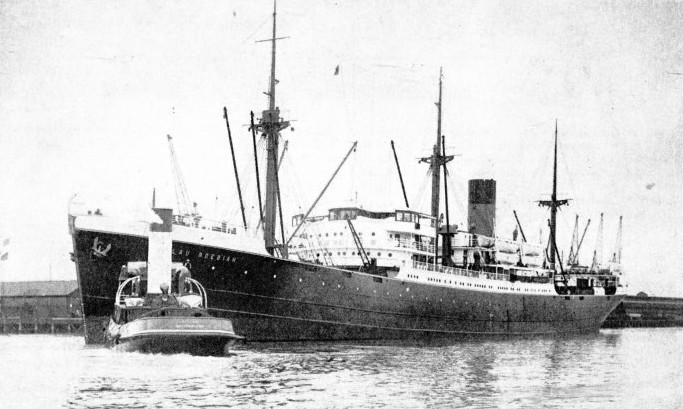

A DUTCH CARGO LINER OF 9,251 tons gross, the Poelau Roebiah is being towed out of Southampton Docks by the tug Hector. A sister ship to the Poelau Tello (illustrated below), the Poelau Roebiah was built at Rotterdam in 1928. She has a length of 495 ft. 3 in. Between perpendiculars, a beam of ft. 1 in. And a moulded depth of 36 ft. 10 in., With a draught of 29 ft. 1 in.

The crack passenger ships of the Rotterdam Lloyd are the Baloeran, 16,981 tons gross, and the Dempo, of 16,979 tons. On their cargo service they have the fast Kota class of about 7,500 tons gross. The Nederland Line also maintains magnificent motor-

The Koninklijke Paketvaart Company is more interested in the secondary services in the East Indies. Its crack ships are the 11,000-

Popular Miniature Liners

The local services in the East Indies are dominated by the Koninklijke Paketvaart Company, which has a big fleet of nearly 150 vessels specially designed for their services.

The Dutch have also shown extraordinary ability and efficiency on the short sea trades, along the coasts of the Continent and also across the North Sea to and from England. The mail service between Rotterdam and London, maintained by the little miniature liners of the Batavier Line and the allied Zeeland Company’s packet service between Harwich and Flushing are exceedingly popular with passengers. Moreover, an immense business with general cargo and foodstuffs is done by various companies. The innumerable Londoners who love to watch the shipping of the Pool from London Bridge all know the “Stroom” boats of the Holland Steamship Company, which have names ending in —stroom.

In all these spheres of activity the Dutch have not only fully earned their reputation for good service but they have also shown the greatest enterprise in keeping their ships right up to date. Their principle is that the best way of overcoming the disadvantages of a slump is to perfect their material, so that even when freights were at their lowest, and everybody connected with the sea had the greatest difficulty in making both ends meet, the Dutch spent large sums in modernizing their ships.

Hull forms which reduced friction, and therefore permitted the same speed with a smaller power, were eagerly tried. Several ships had their bows and sterns cut off to permit the adoption of new hull forms. The greater compactness of the diesel engine caused many steamers to be converted into motorships of greater power, and when the latest forms of high-

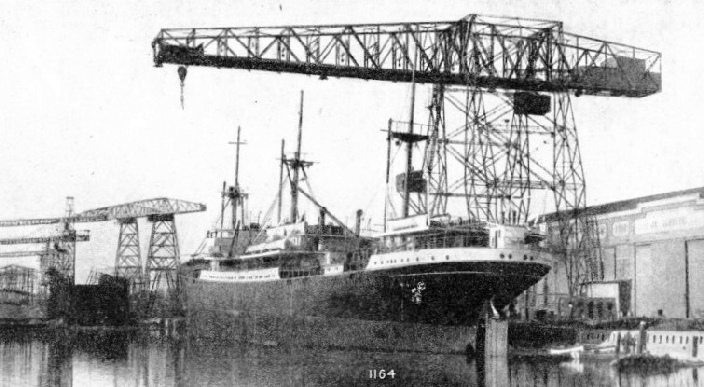

FITTING OUT AT THE DE SCHELDE YARD, in 1929, at Flushing. The Poelau Tello, 9,272 tons gross, is a Nederland Line motorship running on the company’s passenger and cargo services to and from the Dutch East Indies She has a length of 495 ft 3 in., a beam of 61 ft. 3 in. and a depth of 33 feet. Her moulded depth is 36 ft. 10 in On the stocks in the background is the Dempo the Rotterdam Lloyd liner.

A picturesque part of the Dutch shipping industry, whose success many laymen find difficult to understand, is the ocean-

Assisted by labour conditions, the Dutch have now built up such a fine organization for this purpose and enjoy such a high reputation that they have the field almost to themselves. When the giant British floating docks were sent out to the Singapore naval base and to Wellington, New Zealand, there was a public outcry that the work should have been entrusted to Dutch tugs; but the Dutch were the only people who had the necessary material and organization for such difficult jobs to be carried out with reasonable hope of avoiding accident.

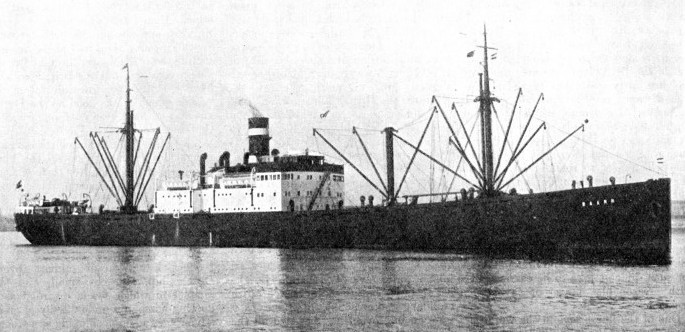

A STRAIGHT STEM AND A CRUISER STERN are characteristic of the Baarn, in addition to the forest of derricks and her white superstructure. The Baarn is a single-

One of the finest tugs in the world is the Zwarte Zee, built in 1933 especially for the most difficult salvage jobs and the longest tows. She is 197 feet long, with a gross tonnage of 793 and a net tonnage of only 77. She is fitted with Werkspoor diesel engines of special design for such a hull, having a brake horse-

Another section of the Dutch merchant service which attracts great attention, largely because it has secured so much of the British coasting trade, is the fleet of motor coasters which have been built during and since the war of 1914 18. Always keen, the Dutch showed great interest when F. T. Everard, the British barge-

Full-

The war broke out soon afterwards, and while it checked any progress in Great Britain it gave the Dutch every opportunity, for the Germans were willing to pay almost anything for all the merchandise that could be taken into their country through the neutral inland waterways of Holland. So the old sailing barges were fitted with auxiliary motors, but, although they were an improvement, they had all the disadvantages of the auxiliary type. Soon the motor was improved and sail became of less and less importance, until the present tendency is to do without it altogether and to use the ship as an efficient full-

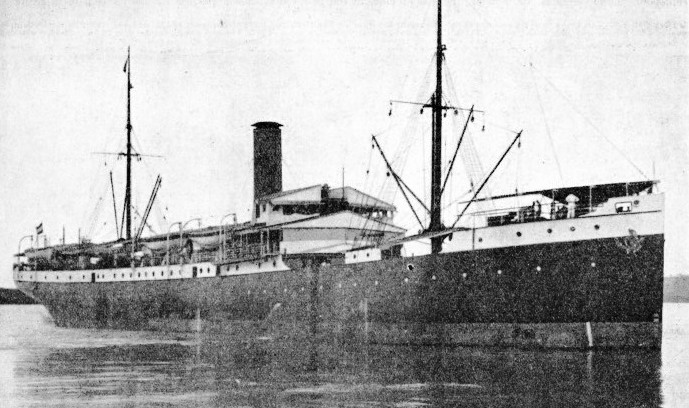

REGISTERED AT BATAVIA, the capital of Java, Dutch East Indies, the single-

The Dutch have built, a great number of these little ships during the last twenty years, and they run them as efficiently as they designed them. The shallow draught that was so useful on Dutch waterways is equally appreciated in the poorer type of British port, of which there are unhappily a large number, and also on the British rivers. In this respect they had an initial advantage over the deeper-

Most of these little Dutch coasters are bought by their skippers on the hire-

The cleanliness of almost every Dutch ship, large or small, and the manner in which she is regarded as a floating home are undoubtedly of great advantage to Dutch shipping as a whole. Other advantages are the high standards insisted upon by the authorities, the give-

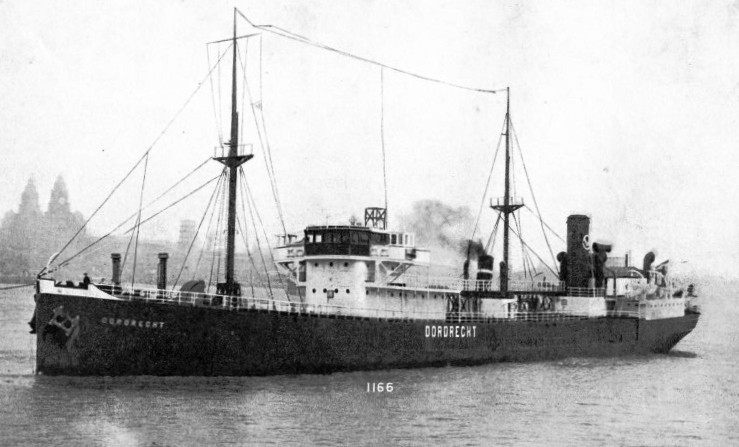

DUTCH OIL TANKER being towed down the River Mersey at Liverpool. The Dordrecht, built at Krimpen in 1928 and registered at Rotterdam, is a vessel of 4,402 tons gross. She has a length of 351 ft. 1 in. between perpendiculars, a beam of 50 ft. 2 in. and a moulded depth of 25 feet. She has a draught of 22 ft. 2 in and is driven by six-

You can read more on “Dutch East Indies Inter-

“The Statendam” on this website.