© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

A Home of British Shipping

Liverpool, Great Britain's premier port for exports, has contributed largely to the progress of British overseas trade, and her name is woven into the pattern of maritime history

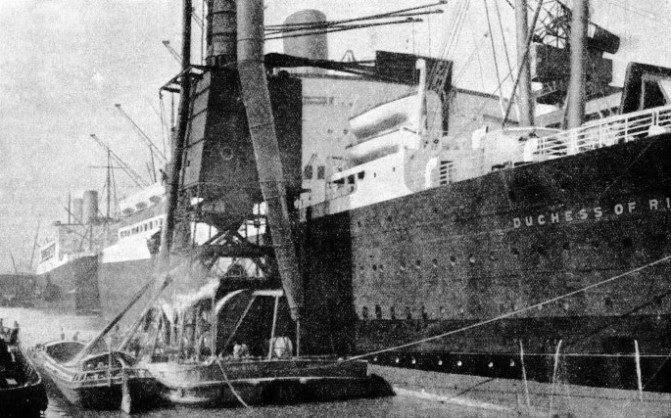

DISCHARGING GRAIN at the Port of Liverpool by pneumatic elevator and unloading general cargo at the same time on the other side of the ship. Liverpool claims to be the world’s largest milling centre after Minneapolis, in the U.S.A. Huge grain warehouses have been erected on either side of the Mersey. The Duchess of Richmond, shown in the photograph, is a Canadian Pacific twin-

ALTHOUGH Liverpool and its port are essentially English, one cannot go there and fail to realize that it is the gateway to the Seven Seas. It stretches its fingers to the other great ports of the world. Big ships and little ships link Liverpool with Canada, Australia and South Africa; with the tropical regions of West Africa; with India, the United States and many of the large South American republics; with Mexico, Spain and Portugal; with Russia, Egypt and the Mediterranean. Liverpool has direct services with all these distant places. They are places we associate with romance, and Liverpool, having traffic with them, is a romantic place also. Here one cannot miss the fascinating sights and sounds inseparable from the great market-

Then there is the tobacco warehouse. This, probably the largest tobacco warehouse in the world, is at Stanley Dock. Seventy-

The Liverpool Landing Stage is a huge raft moored to the shore to float up and down with the rise and fall of the tide. The first landing stage was built off St. George’s Pier in 1847. It was 500 feet long and 80 feet wide. Traffic outgrew it and a new stage was opened ten years later opposite the Prince’s Pier. This stage was 1,002 feet long and 81 feet wide, with three bridges to the shore. Later the two structures were united and reconstructed to form one landing stage 2,063 feet long. This was burnt in 1874 while it was waiting to be opened by the Duke of Edinburgh. The last gas pipe was being connected when, because of some mishap, a disastrous fire broke out and destroyed the stage, the loss being £150,000. A new stage was opened two years later This has been extended at various times to its present length of 2,534 feet, or nearly half a mile.

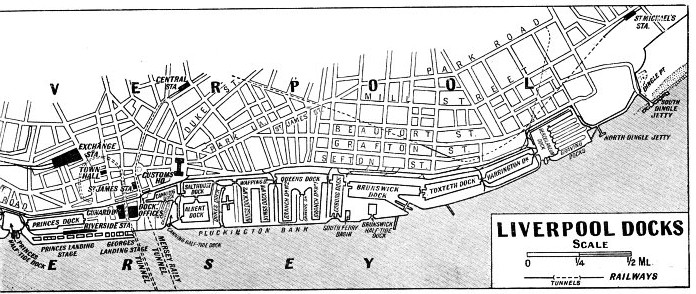

OVER HALF A CENTURY AGO. Liverpool ship-

This remarkable structure is supported by about 200 pontoons, the normal dimensions of which are 80 feet long, 10 feet wide and 6 feet deep. It is kept in position by bridges and booms connected with it and the shore by swivel joints and by mooring chains, the shore ends being made fast to the river wall. The deck level is from 6 feet to 8 feet above the water. Gangways are arranged in fixed positions for ferry steamer passengers from the pierhead. Movable gangways and bridges are provided for liner passengers. The main bridges, about 110 feet long, are used by passengers even at low tide when the angle is steepest; but this angle restricts goods traffic. To overcome the difficulty a floating bridge is provided near the centre of the stage. There are refreshment-

Let us glance swiftly back into history and we shall find the story of Liverpool an integral part of the story of the sea. The ship is the foundation upon which the fortunes of the city rest. Many of the famous lines began at Liverpool and prospered as the port prospered. Famous shipping companies have made it a terminal port. In the days of sail also the great ships in the Atlantic trade made Liverpool their terminal port. Regular steamer communication across the Atlantic began at Liverpool when the wooden paddle steamer, the Britannia, the pioneer Cunard liner, made her maiden voyage to Halifax and Boston in 1840. The first steamship to cross the Atlantic on the Liverpool-

The history of Liverpool goes back even farther than that. In the days of Richard the First the port was probably used for the export of salt brought down the Mersey from Cheshire. Then it undoubtedly commanded some share of the Irish trade because of its geographical position and because of the natural harbour formed by the Pool. The Pool was a creek, but on the site of it the Custom House now stands. The Pool extended over the present Canning Place, Cooper’s Row. Paradise Street and Whitechapel as far as the old Haymarket and gave shelter to the small fishing boats. In the municipal records for the year 1561 is an entry which states that a great storm did much damage, destroying the breakwater of the old haven, which was probably at the entrance to the old Pool. A new haven was soon built, every house in the corporation supplying one labourer free.

In 1715 the Pool was opened as a wet dock, with floodgates to keep the vessels floating during the recess of the tide. The dock was opened in 1715, but was not completed until five years later.

It was the first commercial wet dock constructed in England and the forerunner of the wonderful dock system of to-

The Old Dock was filled in, and the Custom House, dock office and other buildings were erected on the site. Queen’s Dock was enlarged, and the Union, Coburg, Clarence (1830), Brunswick (1832), Waterloo (1834), Trafalgar (1836) and Albert (1846) Docks were built by the Dock Trustees. The monopoly of the Trustees was threatened by the Harrington Dock Company, formed to construct docks on land between the Brunswick Dock and the Herculaneum Pottery; but this company was bought out.

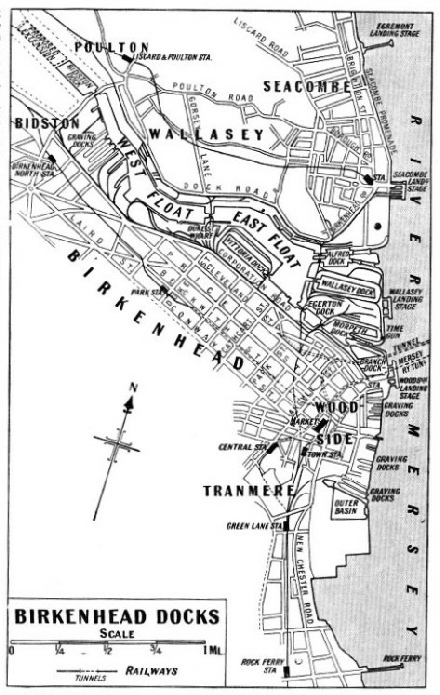

On the other side of the Mersey at Birkenhead a rival company was formed to convert Wallasey Pool into Morpeth and Egerton Docks; these were opened in 1847. On the Liverpool side Salisbury, Collingwood, Stanley, Nelson and Bramley-

Because of various disputes over dues, an Act was passed in 1857 constituting the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board. It met for the first time in January, 1858.

The shipping history of Liverpool is as interesting and as fascinating as any, but we must be content with this brief glance back at it. It is with the modern port that we must concern ourselves. Under the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board the port has been enlarged to keep abreast of the developments of ships and shipping. The most recent docks are Gladstone Docks at the northern end of Liverpool. They were opened by H.M. George V on July 19, 1927.

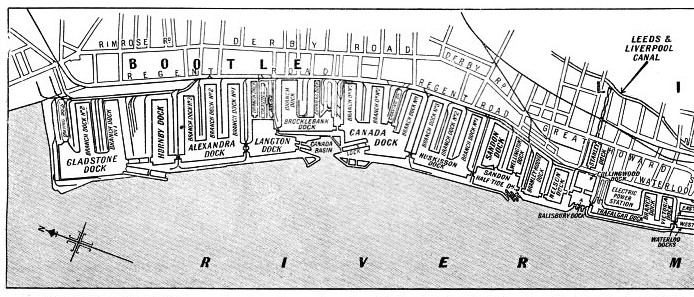

THE LIVERPOOL DOCK SYSTEM, extending along the water-

The distance from Gladstone Graving Dock to Herculaneum Dock, at the southern end of Liverpool, is about six and a half miles. The area enclosed by the docks and basins is about 477 acres, and there are twenty-

Although the entire Gladstone Docks system was not completed until 1927, the famous Gladstone Graving Dock was opened by H.M. George V in July, 1913. This dock cost nearly £500,000, and was then the largest dry dock in Europe. It is used also as a wet dock, the water area being 3 acres 2,585 square yards. The width at the entrance is 120 feet and the length 1,050 ft. 4 in. This dock, built to accommodate the largest ships, proved invaluable during the war of 1914-

Liverpool is situated on the Lancashire bank of the Mersey, but its dock system is on either side of the river. On the Cheshire side, at Birkenhead, the docks are Alfred Dock, East Float, Vittoria Dock, Wallasey Dock and Passage, Egerton Dock, Morpeth Dock and Branch Dock, West Float and Duke Street Passage and Bidston Dock and Passage to West Float. The water in the Birkenhead docks is maintained by pumping from the river. Bidston Dock was opened in 1933. Including Gladstone Graving Dock there are twenty-

The shipbuilding industry, however, did not desert a port that is so inextricably bound up with the sea. Laird’s, who were established on the Mersey in 1824, built their first iron vessel in 1829, and from that time continued to supply merchant and war vessels to home and foreign countries. In 1903 this famous firm amalgamated with Charles Cammell & Co., Ltd., the Sheffield steelmaking concern, and the firm became Cammell Laird & Co., Ltd., by which name it is now known the world over.

IN THE DAYS OF STEAM AND SAIL Liverpool was the port of departure and arrival of many famous express ships competing for the coveted Blue Riband of the Atlantic. Shown here are two vessels, the Nevada and Abyssinia, of the famous Guion Line, at Liverpool. The Guion Line in 1881 held the eastward and westward Atlantic records.

Now we must deal with some of the merchandise which comes up the Mersey and helps to make Liverpool a leading seaport of the world. Grain is one of the largest imports. Figures are sometimes dull things, but we must refer to them now to see how the grain imports have grown to such vast proportions. They are interesting figures, too. In the year 1770 the imports of grain into Liverpool were: Wheat and flour from the Isle of Man, 12 bags; foreign oats, 6,050 quarters; Irish oats, 239 quarters; barley from the Isle of Man, 12 bags; oatmeal, 30 bags. That was in 1770. Now in a normal year 2,000,000 tons are landed at Liverpool, which claims to be the second milling centre of the world, Minneapolis being larger.

Huge grain warehouses have been erected on either side of the Mersey. On the Birkenhead side the Board’s grain warehouses at the East Float can store about 31,000 tons; on the Liverpool side, those at East Waterloo Dock store about 30,000 tons. The warehouses of the Liverpool Grain Storage and Transit Company, adjoining Alexandra Docks, have a capacity of about

110,000 tons; those at Coburg Dock hold about 60,000 tons. The plants of the company are the largest in Europe. Much of the manufactured flour is shipped to other ports by coasting vessels, and thousands of tons are transhipped to other milling centres.

Liverpool has become the natural centre for seed-

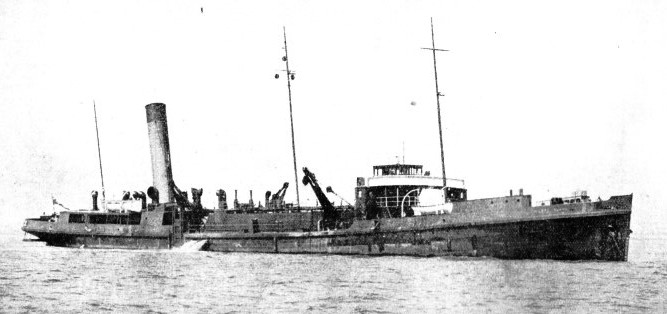

THREE THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED TONS OF SAND IN UNDER AN HOUR from a maximum depth of 65 feet can be removed by the sand dredger Hilbre Island. This vessel, seen at work on the approaches to the Port of Liverpool, was built for the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board at Birkenhead, in 1933. She is a twin-

Liverpool, connected as it is with Manchester by the Manchester Ship Canal, is naturally the port for the Lancashire cotton trade. Once again we must refer to figures, and once again their comparisons are interesting. In 1934 about 2,000,000 bales of cotton were landed at Liverpool. In 1758 twenty-

For some years the West Indies sent more cotton than the United States, but with the invention of new spinning machinery and the end of the American War of Independence the cotton exports of the Southern States increased. Considerable quantities of British-

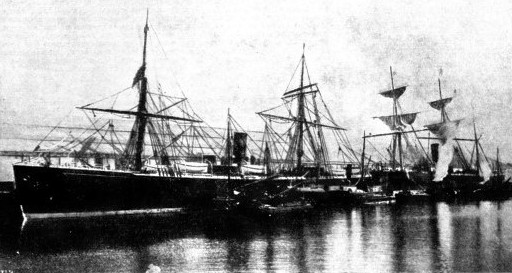

FORMERLY RIVALS to the Liverpool Docks, the Birkenhead Docks lie opposite, on the Cheshire side of the River Mersey. The rival company to that of Liverpool opened the Morpeth and Egerton Docks in 1847. Because of various disputes, however, an Act was passed ten years later constituting the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board, which now controls either side of the river It has greatly improved and extended the port.

One of the most important products that helped to found the fortunes of Liverpool as a port was sugar. The first record of any trade with the West Indies is in 1667. The imports of sugar during the year 1933 amounted to 778,529 tons. The cattle trade is dealt with at the Mersey Cattle Wharf on the Cheshire side; accommodation is provided for about 7,200 head of cattle and 19,900 sheep; extensive chill rooms have a capacity of 3,380 carcasses, and there is slaughter-

As the stranger-

All three buildings are a notable example of the manner in which beauty and utility can be combined. The Docks and Harbour Board offices do not compare in height with those of the Royal Liver Building, but are generally considered to be outstanding as a piece of architecture. Almost square at the base, the building is in the Renaissance style, the front and back being 260 feet in length and the sides 220 feet. On either side of the main entrance, which faces the river, is a figure, one bearing a spinning wheel, representing Industry; the other figure stands with outstretched arms and represents Commerce.

Gateway of the West

Inside the doors is a hall 75 feet across, paved with Calcutta marble and with massive marble columns supporting the galleries. On the floor, below the apex of the great dome, is the sign of a large compass that gives true North and South. Round the lower gallery is a copper band that bears this inscription: “They that go down to the sea in ships and do business in great waters; these see the works of the Lord and His wonders in the deep”.

It is fitting that two of the organizations that did so much to contribute to the prosperity of the port should occupy two of the finest buildings. The Cunard White Star building is little if anything behind that of the Docks and Harbour building in architectural perfection. The Cunard White Star building is also a notable example of the Italian Renaissance. The length of the building from the front of the fa jade on the pierhead is 330 feet. The floor space covers about 100,000 square feet, or rather more than 20 acres, and it would be possible to accommodate in the space some 400,000 people, or half the population of Liverpool.

On the heads of the third floor windows of the Cunard White Star building, looking towards the river, are the arms of the principal ports of Great Britain; down the sides are the ancient emblems of the signs of the Zodiac. Over the doorways and on the projecting base are the nautical emblems Storm and Neptune, Peace and War, Britannia and representative faces of the peoples of other countries, including the Negro, the American Indian and the Australian Aborigine.

An integral part of the history of the sea, an outlet of the corridor that leads from the great hinterland of Lancashire, Liverpool is the gateway of the West. Her name is synonymous with all that is best in maritime achievement. One of the outstanding tributes to that achievement is that in one year during an era of depressed shipping conditions the port loaded and discharged, ships with

12,300,000 tons of merchandise, and sent out and received in the same period 37,500,000 tons of shipping.

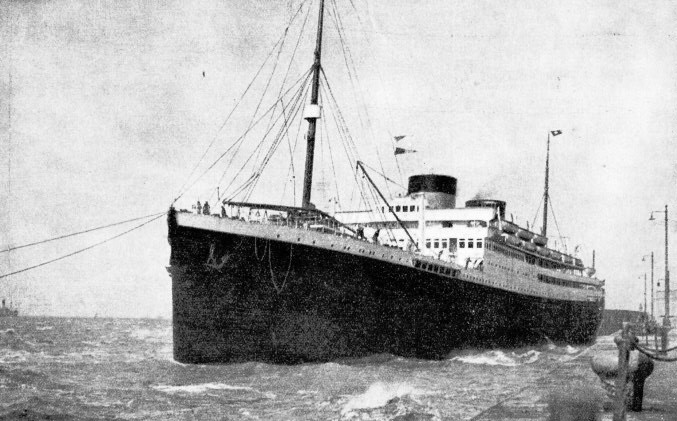

LEAVING THE LANDING STAGE at Liverpool. A fine photograph of the Cunard White Star liner Britannic moving away from the quayside. This twin-

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this article.

You can read more on “London’s Link With the Sea”, “The Manchester Ship Canal”, and

“Pilots and Their Work” on this website.