© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

A Great Ship Sails

“For New York left Southampton”. This is the brief announcement of a liner’s departure. But before sailing day arrives organizations are at work to prepare for a voyage that may take six days or six weeks

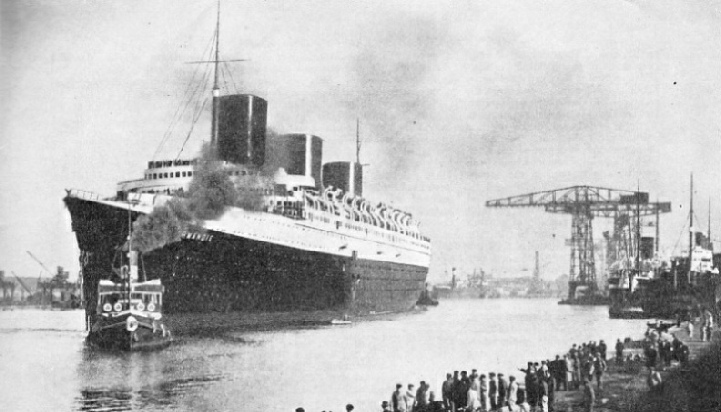

THE NORMANDIE leaving port.

FOR the individual passenger, his embarkation in a giant liner may be a notable event. The voyage may open a new epoch, holding the promise of adventure and romance. Yet the beginning of an ocean voyage is the reverse of dramatic. It is as matter-

The real drama of sailing day lies in the complex preparations that are necessary, and in the organization which completes them so smoothly. A ship’s company is faced with a passage of days -

For all practical purposes a ship is stripped of personnel and contents after each voyage. As soon as she docks from one voyage, she must be prepared for the next. The work begins with the signing-

Various official departments are concerned with the sailing of a ship: the Board of Trade, the Board of Customs and Excise, the Port Sanitary Authority, the Immigration Department of the Home Office (which deals also with emigration), Trinity House (or some other body), which supplies pilotage, and, of course, the Port Authority. Officials from these departments visit the ship constantly during preparations.

The paying-

From the Board of Trade and from the Admiralty come the urgent Notices to Mariners. These contain detailed information of any alterations in navigation rules, or in the positions of buoys, lights and channels. For instance, the entrance to Southampton Harbour, between Cowes Roads and Southampton Water, is an S-

The Mercantile Marine Department of the Board of Trade is concerned with many of the other stages of a ship’s preparation, culminating in the last stage of all, and the issue of “Survey 32”, explained below. Each stage may be examined separately, though the events do not occur consecutively.

Any ship carrying over fifty third-

Another safety-

Bond of £2,000

Upon receipt of the report that the load-

Another Board of Trade form which must be completed for emigrant ships is “Survey 47A”. This covers what is known as the “continuing bond”. The owners and the master of every emigrant ship lodge a bond of £2,000 with the Crown to ensure that certain provisions of the Merchant Shipping Acts shall be observed. The bond is worded in odd-

“Know all men by these Presents that we … are held and firmly bound unto our Sovereign Lord Edward the Eighth, by the Grace of God of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and of the British Dominions beyond the seas, King, Defender of the Faith, in the sum of two thousand pounds to be paid to our Lord the King, his heirs or successors, for which payment well and truly to be made we bind ourselves and each of us, jointly and severally, our heirs, executors and administrators firmly by these Presents. Sealed with our seals.”

The provisions ensured by the £2,000 penalty in the bond include that “the ship shall at the time of her departure be in all respects seaworthy”; that “throughout the voyage at least four quarts of pure water shall be allowed daily to each steerage passenger”; and that “any engagement made at the beginning of a voyage to call at an intermediate port for fresh water shall be fulfilled”.

This is known as a continuing bond, so called because it is considered sufficient for each successive master to endorse the original bond. Although it is a Board of Trade form, its completion is generally entrusted to the Chief Customs Officer of the port -

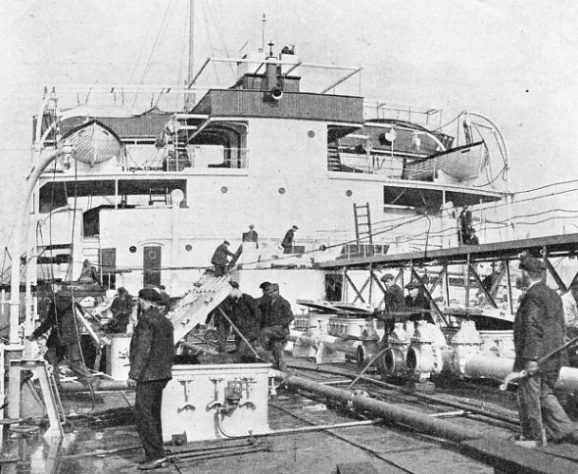

LAST LINKS WITH THE SHORE. The gaily-

The final form to be completed before the ship sails is the Board of Trade “Survey 32”, mentioned above.

This form, duly signed by the Emigration Officer, is a Certificate of Clearance which contains complete information as to the ship’s itinerary, details of the passengers in each class, and of the crew; “Survey 32” also gives the total numbers aboard, the amount of “clear” space, and the number of beds. It closes with the following certificate:

“I hereby certify that the particulars inserted in the above form are correct. I also certify that all the requirements of the Merchant Shipping Acts relating to emigrant ships, so far as they can be complied with before the departure of the ship, have been complied with, and that the ship is, in my opinion, seaworthy, in safe trim, and in all respects fit for her intended voyage; that she does not carry a greater number of passengers than in the proportion of one statute adult to every five superficial feet of space clear for exercise on deck; and that her passengers and crew are in a fit state to proceed.”

Before this all-

The department next in importance to the Board of Trade is the Board of Customs and Excise. Returns must be made to the Customs officers of dutiable supplies, such as food, drink, and tobacco, which the chief steward may wish to take aboard the ship. As they are for consumption afloat, these escape excise duty and so must be withdrawn from a bonded warehouse, where they are lodged under arrangements made by the Customs authorities. The appropriate returns are accompanied by a request for the release of such goods, or for their supply by various firms direct, free of duty. Once the supplies are aboard, a “Victualling Bill” must be filled out, giving detailed particulars of the dutiable goods taken aboard. The Customs officials must also receive from the captain a return of the total amount of dutiable goods which it is intended to carry as stores or cargo. A declaration of the total number of passengers outward bound from British ports is required also. On another form, oddly entitled “Entry Outwards”, the Board of Customs and Excise requires a report of the inward cargo still remaining on board, and a certificate of the exact position of the load-

Relic of Sailing Days

The next department to be considered is the Port Sanitary Authority, responsible that the ship’s company is in good health. The Port Medical Officer attends the muster of the crew, passing them as fit. He looks especially for symptoms of virulent infectious diseases such as typhus, smallpox and cholera; and will, if necessary, prohibit any one, crew or passenger, from sailing. Satisfied with both crew and passengers, he issues his Bill of Health. This is another quaintly-

“To all to whom these Presents shall come. I, the undersigned Officer of His Majesty King Edward in the Port of ... in the City or Town of ... send greeting. .... Now, Know ye that I, the said Officer, do hereby make it known to all Men, and pledge my faith thereunto, that at the time of granting these Presents, no Plague, Epidemic, Cholera, nor any dangerous or contagious disorder exists in the above Port or Neighbourhood. In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my Name and Seal of Office, on the Day and Year aforesaid.”

The Immigration Department of the Home Office is represented at the quayside on sailing day. It is the duty of its officials to examine the papers of outward -

MAKING READY FOR SEA. This is comparatively easy in a tanker, as shown above. In the liner, however, the Marine Superintendent is responsible for all the refitting, refuelling and repairs, and for the replenishment of stores. The various departments work under his control. He has to attend to the inspection of ship’s boats, the overhaul of deck gear and the testing of navigational instruments. The Marine Superintendent also arranges the time of departure and engages tugs and pilots.

The Port Authority is not generally a government department, but its officials must be satisfied, before a ship sails, that all her port dues have been paid; and they are consulted as to the exact time for sailing. Their chief executive on the quayside is the Dock or Harbour-

Trinity House is the body controlling outside pilots in British waters, i.e. those outside rivers and ports. It is to this organization that application must be made for a pilot who will navigate the ship through coastal waters. The coastal waters are nowadays covered by the “choice” pilot who will handle the ship in compulsory waters.

These official measures taken by law to ensure the safety and health of the passengers and crew are administered efficiently and with a minimum of officialdom. For about ships there is that which promotes comradeship, co-

While the ship is in dock, the Marine Superintendent is virtually her captain. He takes over as soon as the first hawser is made fast and relinquishes his responsibility only when the last hawser is cast off. Under his supervision all the papers are handled and passed through; refitting, refuelling, repairing and replenishment of stores are all carried out by the various departments under his authority. His work, well done, ensures that the ship about to sail is “in all respects seaworthy”. The work is even more complex than the formalities already described. There is so much detail, and so little time for hitches.

The Marine Superintendent’s office -

He directs the taking aboard of thousands of tons of fresh water and oil fuel. External painting and cleaning are in the hands of his department. The ship’s boats must be inspected, and necessary repairs carried out. Deck gear must be overhauled, navigational instruments and gear must be tested. Their efficiency depends on the Marine Superintendent’s thoroughness.

Time of departure is arranged by him, and he engages the tugs and pilots. As stated above, his work is over only when the last hawsers are cast off and the great liner is under way.

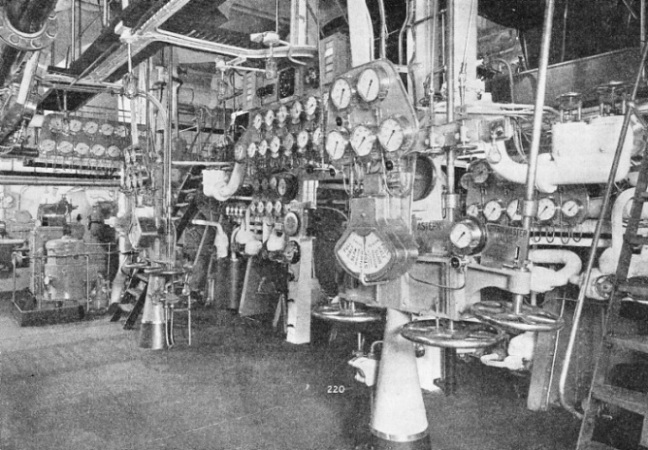

THE ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT has to ascertain that the great plant which drives the liner is in order before the ship can leave. Main propelling machinery, the auxiliary engines for operating winches, derricks, the cooking apparatus, the refrigerating plant, and heating and ventilation systems have all to be inspected and repaired where necessary. This photograph shows the engine-

Meanwhile the other departments are ceaselessly at work on their own tasks. The Furnishing Department -

The Furnishing Department, too, is responsible for all the furniture, carpets, linoleum, tapestries, curtains, hangings and pictures in the ship. The floor coverings alone may cover many acres. The interior decoration is in this department’s hands. Every time a ship docks some repainting of the passengers’ quarters is carried out; and every square inch is thoroughly cleaned. Yet not a painter, carpenter or joiner will be visible on sailing day. There is a rigid rule that all work must be finished before the passengers come aboard, and it goes ill with the department if the rule is broken.

Below decks, in the engine-

The Problem of Stores

When coal was used, hundreds of men took days to carry aboard from barges the baskets of coal and empty them down the coal-

As well as the main engines and boilers, there is a mass of auxiliary machinery to be tested. Special machines are installed aboard a luxury liner to work the cargo derricks, anchor windlass, warping winches, steering gear, bulkhead doors, cooking machinery, refrigerating plant, heating and ventilating system, and sanitary and domestic water supplies. The electric generating plant alone develops sufficient power to supply current for a medium-

Not only must the shipping company’s staff be assured that all the machinery , is in a state of complete efficiency, but stringent Board of Trade regulations have also to be satisfied; and the Classification Societies, previously mentioned, insist on their own exacting standards on behalf of the insurance underwriters.

Great quantities of engineering stores have to be taken aboard, in addition to the fuel, oil and water, for the main engines and boilers. There may be as. many as a dozen different kinds of oil used aboard the ship for lubrication, illumination and cleaning. Tool kits may have to be replenished or replaced. Cotton waste, soap, lime and soda, and carbon dioxide for the refrigerating plant, must all be supplied in sufficient quantities.

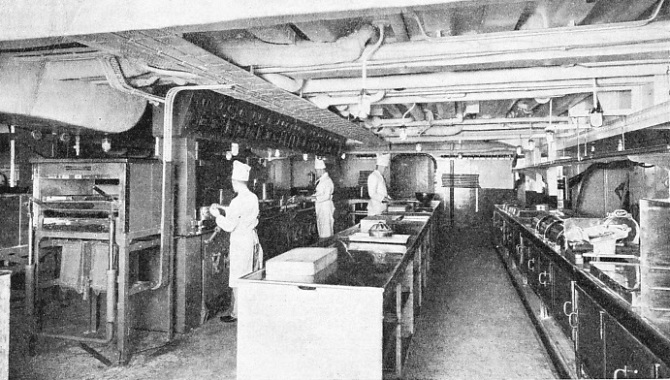

PREPARATIONS FOR OVER 50,000 MEALS may have to be made by the Chief Steward and the Catering Department. This photograph shows the modern kitchen in the P. & O. liner Strathmore. Her complement of 1,110 passengers and 515 crew involves the serving of nearly 4,900 meals a day if every berth is occupied. The voyage from Tilbury to Bombay takes nearly three weeks.

The last job of the Engineering Department -

A long blast on these same sirens at sailing hour proclaims that the Engineering Department’s work is done, and that the ship is once more ready for her 3,000-

She sails, a complete city, self-

Meanwhile, the kitchen equipment is inspected; utensils are repaired and replaced. A stocktaker goes over the inventory of china, glass, and earthenware, amounting to approximately 100,000 pieces, as well as 25,000 pieces of cutlery.

A Task Well Done

Thousands of empty bottles are put ashore and replaced by thousands of full ones. In addition, all dutiable stores taken aboard, eatable or drinkable, must be reported on the Victualling Bill to the Customs. All surplus stores are listed and checked.

The Freight Department is just as fully occupied. On a “quick turn-

There are many other detailed preparations for sailing. The ship’s doctor, for instance, must restock his dispensary. The library stewards take aboard new books, magazines and papers; they also procure a large quantity of stamps. More than 10,000 letters have been mailed during a single voyage.

Electricians and plumbers attend to the gymnasium equipment and to the swimming pool. Wireless experts are busy in the radio room. There is even a ship’s gardener, who is in charge of the thousands of plants and flowers needed for decoration.

When all the work is completed, the Marine Superintendent inspects the ship before handing over to the captain. He sees work superlatively well done; complex tasks which have been performed in the minimum time. The record “turn-

However accustomed the man in charge may be, the moment when the last gangway goes cannot fail to be a proud one -

THE PREMIER PORT in the British Empire for the large liners is Southampton. This great port handles some thirty-

You can read more on “Launching Ceremonies”, “Pilots and Their Work” and “R.M.S. Strathmore” on this website.