© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Launching Ceremonies

The methods of launching a ship vary considerably and the ceremony, as this chapter shows, occasionally involves the use of astonishing innovations

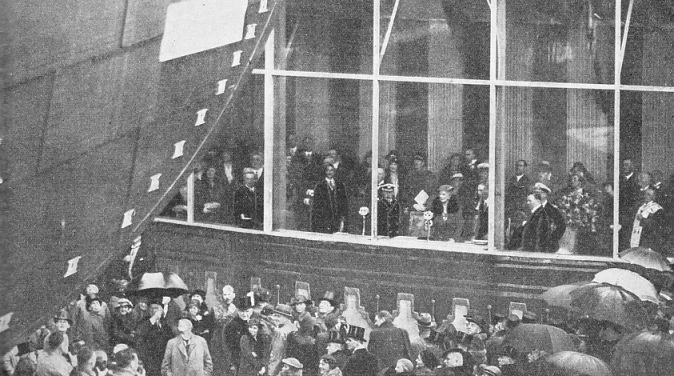

AN HISTORIC EVENT. The launching of the giant new British liner the R.M.S. Queen Mary on September 26, 1934, at John Brown and Co.’s shipyard on the Clyde. This picture shows His Late Majesty King George V with Her Majesty Queen Mary, who named and launched the great ship. Until the launching ceremony the name of the vessel was kept strictly secret.

THE launching and christening ceremony is the great event in a ship’s career. No matter how great a name she may make for herself afterwards, or how many records she may break, the memory of all who attended her launching will inevitably return to that first occasion when she slid down the ways, gradually gathering momentum. The moment when she took the water and made her curtsy to the guests at the head of the slip before she surrendered herself to the care of the attendant tugs will be long remembered. However many launching ceremonies may have been experienced, most spectators will still know a thrill as they see a ship go down the ways.

No matter what country it may be, Eastern or Western, savage or civilized, the launch of a ship is always the occasion of a picturesque and impressive ceremony. Even among the maritime nations which have adopted identical shipbuilding machinery and scientific procedure for bringing the ship to the launching stage, the details of the ceremony vary according to the spirit and temperament of the people.

In most countries, however, the ceremony is only a variation of that familiar in Great Britain. The personage asked to sponsor the ship stands on a platform built round her bow as she rests on the slipway. At the exact moment that the tide serves to let the ship take the water, the sponsor breaks a bottle of wine over the vessel’s stem, wishes good luck to her and to those who sail in her, operates the machinery that releases her and lets her slide down the ways.

There is room in this ceremony for many modifications, even in Britain. Sometimes the bottle of wine is suspended from the bow of the ship by a white silken ribbon, so that the sponsor has only to let go for it to fall against the ship’s side. Sometimes it is held in the hand to break; a method that is apt to scatter wine over the launching party, and sometimes the bottle rests in a cradle against the bow of the ship, held down against a strong spring. The moment a button is pressed the spring is released and the bottle is carried against the ship. Similarly, to operate the launching mechanism, sometimes an electric switch is pressed, sometimes a silken cord is cut; but with either method a weight is released to fall on the trigger that is holding back the mass.

In 1934 a new launching ceremony was introduced, when two big liners were launched by wireless. On the first occasion a ship for the Holland-

With their love of everything that is picturesque, the Japanese naturally take a keen interest in the ceremony and give it many charming little touches which are typically Japanese. Over the bow of the ship that is to take the water is suspended a circular cloth cage of red and white stripes. As the ship is released this cage is ripped open and a number of song birds are freed; these birds circle round the ship as she goes down the launching ways. The belief is that the birds, in gratitude for their liberty, will always take an interest in the ship and guide her to safety in times of peril.

Sometimes, but not always, flowers and flower petals are enclosed with the song birds in the cage, the petals falling over the launching party in a cloud as the cloth is ripped. The ceremony is generally preceded by a short religious service.

AFTER THE CRUCIAL MOMENT. The launch of the Queen of Bermuda as she slid into the water. She is a vessel of 22,575 gross tons, and was built at Barrow-

In Europe the Latin peoples have, perhaps, the greatest inclination to add picturesque touches to the launching ceremony. Italian shipbuilders like to complete the ship on the launching ways instead of sending her round to the fitting-

Chinese launches are less artistic than Japanese, but they are certainly impressive. All round the ship incense is burned to propitiate the gods. Every spectator is provided with fireworks. He is expected to make the greatest possible noise with them as well as with drums or tom-

Superstition with launches is not, however, confined to the Chinese. It is doubtful if superstition persists more strongly anywhere in Great Britain than in the shipbuilding world, especially when the launching of a vessel is concerned.

On the North-

This same area of hard-

Another superstition which has never had much hold on official minds in the Navy, and which is rapidly dying out, is that the worst of luck will follow the ship whose name is divulged before the ceremony. Nowadays, the names of all warships, and of at least two merchantmen out of three, are well known long before the christening ceremony. But in the days of the old racing clippers such premature revelation would have been regarded as foolhardy. Recently the Cunard White Star Line, with so much at stake, kept the name of the R.M.S. Queen Mary a secret until her Majesty Queen Mary pronounced the christening formula.

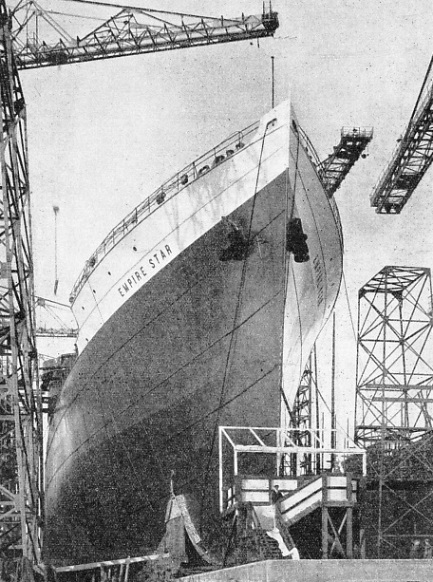

BEFORE THE LAUNCH. A bow view of the motor ship Empire Star, built at Belfast for the Blue Star Line in 1935. The ship has a gross tonnage of 10,800, a length of 516½ feet, a beam of 70 feet and a depth of 43 feet.

It is considered most unlucky if the sponsor fails to break the bottle at the first attempt, and a ship is held to be practically doomed if she enters the water with the bottle still intact. When H.M. battleship Albion was launched at the Thames Ironworks in 1896 by Her Majesty Queen Mary, then Duchess of York, one of the principal officials of the shipyard was an enthusiastic teetotaller and, either by his orders or from a desire to please him, the champagne had been emptied out of the bottle and water substituted. To hide the deception, the bottle was swathed with decorative ribbon until it had a thick padding. Three times the Duchess, threw the bottle; three times it bounced off the steel bow. In despair, she handed it to a male spectator standing by. He tore off the ribbon, revealing the imposture, and finally smashed the bottle just as the ship was moving out of range. Immediately afterwards fifty people were drowned when the backwash from the ship’s displacement carried away a crowded staging.

Allied to superstition is custom, and that exists in full measure in every shipbuilding district. Among the innumerable customs, logical and illogical, that were formerly always observed by Clyde shipbuilders were certain acknowledged relaxations of discipline and shipyard routine.

When a wooden ship was launched it was customary for the young carpenters and shipwrights’ apprentices to conceal themselves on board, as far forward as possible. Immediately she started down the ways they emerged to secure the ribbons and rosettes that were left hanging. These were much prized by the Scottish girls in the shipbuilding districts. Another custom, which was not appreciated nearly so much by the youngsters, was for all the apprentices who could be secured to receive a sound thrashing or ducking from the older hands. The justification was that if the apprentices were not doing anything wrong at that particular moment, they had been or soon would be misbehaving.

Ceremonies, superstitions and customs go so far back into the mists of history that it is impossible to trace their origin. The ancient Mediterranean warships took the water garlanded with flowers, but often enough human sacrifices were offered to Neptune at the same time. At the launch of the Viking long-

Perhaps the most picturesque ceremony was in Tudor days, when the Navy was beginning to acquire popularity. In those days the ship took the water without any ceremony, but as soon as she had been secured alongside the quay, or fitting-

To the usual fanfares he marched round the poop, acknowledging the cheers of the spectators. He then seated himself on a decorated chair. Before this was a pedestal on which rested a silver goblet of wine. Giving the ship her name and wishing her God-

AN UNUSUAL PROCEDURE. H.M.S. Deptford, a sloop of 1,000 tons, was constructed on the bottom of a dry dock in Chatham Dockyard, Kent, instead of, as is usual, on a building slip. On the day of the launch the water was admitted through the sluices of the dock gates. When the water in the dock was level with the river outside, the sloop was towed away to be fitted out for service.

This was a picturesque ceremony, but it was only to be expected that there would be somebody in authority who strongly objected to its extravagance. So the master shipwrights secretly stretched a net under the water alongside the ship and salved the goblet as soon as the excitement was over. When the courtiers at the Stuart Courts were more needy, there arose an open quarrel between the King’s Lieutenants and the master shipwrights about the reversion of the goblet. This brought the whole ceremony into disrepute and led to its abandonment; but it was restored by Charles II with the custom regularized. The goblet was presented to the master builder as his acknowledged perquisite.

This picturesque old custom was gradually abandoned as being out of keeping with the spirit of the age. For some time there appears to have been no regular launching or christening ceremony at all.

Just when the use of a bottle of wine was begun cannot definitely be discovered, but the custom was apparently due to the efforts of the shipyard workers themselves, without any encouragement or co-

Gradually the Admiralty began to appreciate the virtue of a little ceremony and, where the King’s ships were concerned, made it official. About 1810 there began the custom of asking a lady to perform the christening ceremony. This has been practically universal ever since. One of the earliest instances was unfortunate. A Royal Princess was invited to break the bottle over the bows of a new ship that was to be launched at Plymouth Dockyard. She missed the ship altogether, but the bottle landed on the head of a spectator standing beside the ways, doing him serious injury, for which he later obtained compensation through the courts.

Ever since then the Admiralty has taken the precaution of making the bottle fast to the bow of the ship by a piece of ribbon. In dockyard launches the bottom of the bottle is generally filled with lead to ensure that it breaks.

Wine is the traditional christening medium of the ship, but its quality may vary. “Old Hall” of Aberdeen, builder of some of the finest clipper ships, would invariably send his office boy to a certain grocer’s shop on the morning of the launch, with instructions to buy a shilling bottle, of “christening wine” of champagne character. He would always make a joke of this exhibition of parsimony.

On the other hand, there are many shipowners who maintain that the best of wine is not too good for the vessel that is to carry their fortune. Many owners who object to alcohol on principle have used water. Then the workers shake their heads and say that the ship cannot possibly have any luck. There are many instances of water-

BUILT AT BELFAST. The launch of the Duke of York in March, 1935. This vessel, of 3,700 gross tons, was constructed by Harland and Wolff for the L.M.S. mail service between Heysham (Lancashire) and Belfast. She has a length of 339 feet, a beam of 52 feet, and a depth of 18 feet, and is propelled by four steam turbines driving two screws through reduction gearing. She is capable of 21 knots.

Where the owner is teetotal, water can be respected, and perhaps there was an excuse for ginger wine in American launches when the prohibition law made the use of wine illegal. But some substitutes ridicule the traditional ceremony. In 1927 a ship launched on the Clyde was christened by having a coco-

Nowadays a religious ceremony is part of the launching of every ship of any importance. In Roman Catholic countries it has never been abandoned. The sacrifices made by the Romans and Vikings were made with a religious object. In his diary of the year 1676 Henry Teonge, a chaplain in H.M. Fleet, describes the launch of a new galley for the Knights of Malta when his ship was visiting the island. The ceremony began with two hours of hymns and anthems, after which two priests went on board and laid their hands in benediction on every mast and major fitting, sprinkling holy water and finishing up with a public blessing. There is no doubt that the reverend diarist was impressed in spite of himself. He came from an inland parish and apparently did not know that in his own country the religious ceremony had been an integral part of the launch of the ship during the Commonwealth, although it was stopped in the early days of the Restoration. The ceremony did not return until 1875, when two parties used their influence. One was Admiral King-

Immediately after the ship has taken the water the company generally goes into the mould loft, the biggest room in the shipyard, and sits down to a banquet lunch. In the evening the workmen have their own celebration, usually described as a “ball”. After the lunch there is an excellent opportunity for happy speeches and the general passing of compliments, so that the visitors go away thoroughly satisfied with a charming ceremony. Visitors are not allowed to see anything of the anxiety which accompanies every launch. The fact that accidents happen so seldom is a tribute to the careful manner in which everything is prepared and the efficiency of all hands; but the possibility is always there.

The ship is built on a slipway leading down from the shipyard into the water, known as the permanent ways, standing ways or ground ways. When she is ready for the launch there is built under her a cradle, generally called the sliding ways, between which and the permanent ways tallow, soft soap and oil are placed as a lubricant. Unfortunately, this lubricant may freeze in cold weather and act as a brake instead.

The cradle is built up under the bow and stern into heavy “poppets”, the bow especially having to stand a tremendous strain. The cutting of the cord by the sponsor, or the pressing of an electric button, knocks away the dog-

A HAPPY CEREMONY. H.R.H. the Duchess of York, accompanied by the Duke of York, about to launch the P. & O. liner Strathmore on April 4, 1935. This liner, of 23,428 gross tons, was completed in the September of the same year. The vessel was built at Barrow-

You can read more on “Bermudian Luxury Liners”, “Building a Liner”,

“RMS Queen Mary -