© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Shipbreaking Industry

In the days of the “wooden walls”, a ship condemned to destruction was often burned or even carefully “lost” in some convenient spot. To-

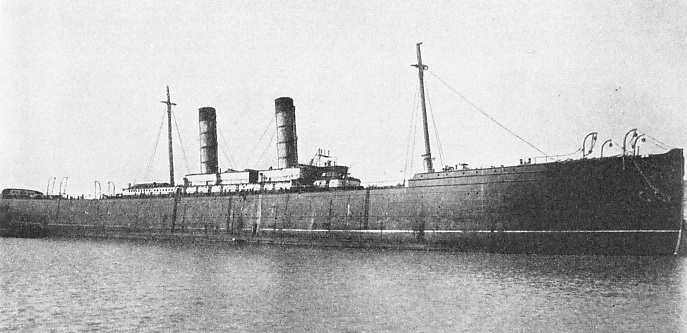

THE LAST OF A CUNARDER. The Servia, 7,392 tons gross, was broken up at Preston, Lancashire. She was built for the Cunard Line in 1881 at Glasgow. Her length was 515 feet, her breadth 52 ft 1-

THE business of shipbreaking is one of the numerous industries which have grown up round shipping and the sea. It was apparently first practised in the dismantling of ships which had been driven ashore in bad weather. Those who had the legal right to a wreck, and often those who had not, used the materials for building their huts ashore or for any other purpose.

Shipbreaking as an industry does not appear until a later date, but in Tudor days it was the regular practice to break up worn-

When there was no shortage of material, and the ships could be carefully and leisurely built, it was not as a rule worth while breaking up a wooden ship. She was generally taken to some quiet spot and left to fall to pieces with the minimum of trouble to her owners. Even naval ships were sometimes treated in that way and to the present day small vessels and barges which have no sale value will often be carefully “lost” in some out-

As a rule, however, even the oldest ship has some value -

For many years Castle’s took the greatest care of the figureheads of the ships which they broke up. When, after a long period of neglect, the Admiralty suddenly realized that such trophies were of great value to the morale of the Service, it was enabled to make the famous dockyard collections principally through the co-

Shipbreaking can he practised only where the conditions and labour are suitable. In the countries where these are not suitable the merchants have to rely on imports, and a surprising number of ships are employed carrying full cargoes of the materials of their predecessors. In the United States, where labour costs are excessive, shipbreaking can be done only when the ship is of a type which lends itself to mechanical treatment. Wooden ships do not, and for a long time it was a usual American practice to recover all that was really worth while from a wooden ship by burning her.

She would be stripped of the fittings, which were easily removed and then towed inshore at the top of high water, at a spot where there was a large rise and fall. She was then set on fire, generally assisted by barrels of tar or some such fiercely burning material, and by the time the ebb had finished there was little more than a heap of ashes left on the foreshore. From these the metal fastenings and the copper sheathing could be collected with little difficulty and sold for further use.

Even in countries where labour is cheap, the materials of wooden ships could be profitably used again only when they were of oak, teak or similar timber. The majority of ships were of soft wood, which did not last for any time as garden furniture, but these were cut up into small pieces. Before the war of 1914-

When ships built of iron or steel began to wear out, the business altered completely. It was impossible to break them up with the primitive tools of the wooden scrapper -

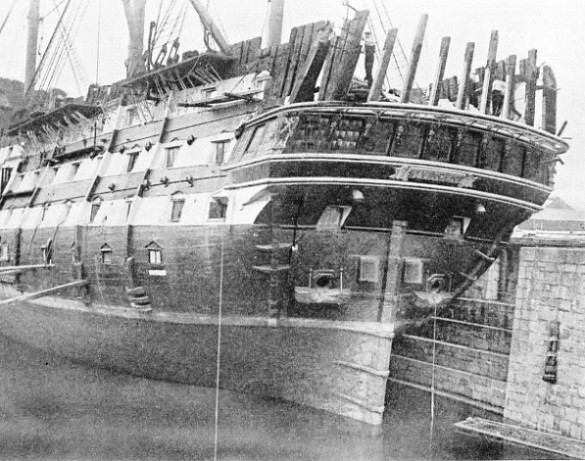

WEST COUNTRY “WOODEN WALL”. H.M.S. St Vincent was built at Devonport in 1815 and was broken up on the Thames in 1906. She had a length of 204 ft 11-

Great Britain had a big start over her competitors in iron and steel shipbuilding on account of her natural resources, and many of the foreign shipbuilders were glad to buy British scrap to work into their new construction. Well over fifty years ago Denny Brothers of Dumbarton started to use forgings of scrap steel for their new ships and found that it answered perfectly. They began making the stems of all their seagoing steamers, a part of the ship which demands great strength, of scrap steel. They soon extended it to other parts, experimenting until stern frames up to a considerable weight could be made of scrap steel without difficulty or risk.

Other firms followed suit and nowadays the accurate blending of the right proportion of scrap with new metal is one of the most scientific parts of the work of the metallurgist and is not only practicable but also economical. The proportion of scrap varies with the properties of the metal with which it is mixed, so that the demand of some countries is more than that of others, and it is subject to the fluctuations of the various industries which use scrap. The current price of scrap steel is bound to have a big influence on the plans of the shipowners and shipbuilders. When the price is low the owners keep their ships running as long as they can and do not order so many new ones.

The British scrapping industry was the pioneer, but it was gradually copied in other countries which wanted materials for shipbuilding and other purposes and had little or no natural supply. Many of these countries evolved most ingenious methods of using the scrap in new manufacture, and in the years preceding the war of 1914-

Sometimes the shipbreaking companies were in a position to run their ship with a last cargo to the country which had bought her, but the majority were bought with delivery in England and were taken out by a temporary crew of runners. Those going to Italy were usually loaded with a cargo of coal, which went a long way towards paying the expenses of delivery even at the lowest freight, and more than one came to grief on the way out. The owners of liners which had made a great name for themselves on the passenger services were anxious that the public should not identify them with a final disaster and frequently insisted that the names should be changed before they left a British port. The simplest way of doing this was to chip off the final letter of the name with a chisel so that many ships have made their last voyage under curious tallies.

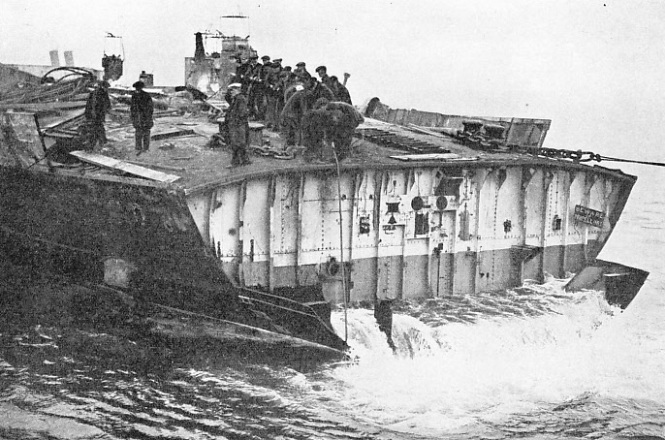

THE AFTER END of a famous battle cruiser H.M.S. Lion. The flagship of Admiral Beatty at the battle of Jutland, she was among the warships scheduled for scrapping under international treaty. She was cut in two at Hebburn (Co. Durham), and the stern part was towed down the Tyne to Blyth (Northumberland), to be broken up. Because of a heavy ground swell, the stern part broke away from the tugs, but it was picked up again and the destination was reached. The photograph shows the crew hauling in the broken tow rope. H.M.S. Lion, completed in 1911, had a displacement of 26,350 tons and a speed of 30 knots. She was armed with eight 13.5-

Nowadays the British shipbreaking industry is run on the most scientific lines, and many big firms are engaged in it. A large amount of capital is sunk in the business. Extensive yards have been acquired and given the most up-

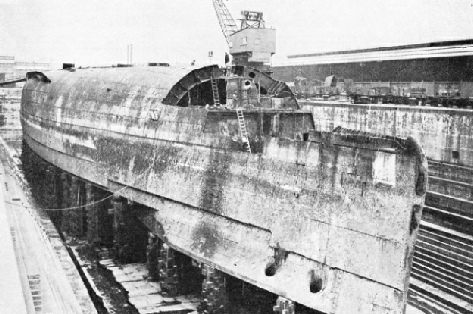

Formerly ships were broken up in dry dock whenever one was available, but that was expensive and nowadays this is done only in exceptional circumstances. The German ships salved at Scapa Flow, for instance, are towed bottom upwards down to the dockyard at Rosyth, which is now almost disused, and there dealt with in one of the dry docks left idle by the departure of the fleet.

As a rule the shipbreaking firm carefully selects the position of its yard, used exclusively for the purpose, with many factors in mind. It must be as handy as possible to the steel works to save transport expenses, for railway rates are heavy on pieces of any size and it is costly to handle them. The site must have a foreshore as long as the ships to be scrapped, and at high water sufficient depth for them to be floated in, although this demand is reduced by making the ship as light as possible and then driving her ashore at full speed. This is an impressive sight and the fact that it ruins the bottom of the ship is of minor importance. It has to be broken up anyhow. A 10-

In contrast to the tools used in the old wooden scrapping yards, the equipment of a modern establishment is exceedingly elaborate and expensive. The first necessity is plenty of power, for many of the machines are ponderous by the nature of their work. Big electric motors are the favourite sources of power.

Plates of hard steel up to 2-

Oxy-

There is usually a good deal of cast iron in a ship, especially in the engine room, and this is still broken up into convenient pieces by the methods that have been in vogue for three-

The industry has been revolutionized within recent years by the introduction of oxy-

The industry has been revolutionized within recent years by the introduction of oxy-

FATE OF A FRUIT SHIP. The Jamaica Planter, shown at Bo’ness, West Lothian, was one of the fast banana ships engaged in the fruit trade between British ports and the West Indies. Formerly the Highland Loch, this vessel was built in 1911 at Birkenhead. Her length was 413 ft 9-

The use of these burners in foreign yards left no alternative to their adoption in Great Britain, and now it would be quite impossible to break up a steel ship economically without them.

The shears and the oxyacetylene plant are used for cutting the scrap into convenient size for the ordinary steamer would load badly with the bigger pieces, and the railways probably would not consider carrying them at all. Tramps are almost invariably used for the transport of scrap and the charterers want to get the utmost use out of the tonnage for which they are paying. A ship making her last voyage to one of the shipbreaking countries in Europe, or even out to Japan, will often take a cargo of scrap from other ships, but the demand for transport is far too big to be completely satisfied by that means.

In the old days there was an appalling waste in the process, for as a general rule the shipbreakers were interested only in the steel or metal for which they had a market, and anything else was disregarded. Really fine furniture, good for many years’ service, was either smashed with an axe and fed into the furnaces, or else given as a present to anybody who cared to take it away. Many a waterman round the yards, made welcome to any odd thing that he cared to take away, has found a good market for it ashore. That, however was in the old days.

Among the pioneers or the more efficient system of to-

Relics of Famous Ships

The other firms in the industry all work on the same system nowadays, with results that depend largely on the size and organization of the firms, but everything is carefully priced. The old sailor who wants a ships bell to hang in his hall, as so many old sailors do, no longer gets it at so much a pound for old bronze.

Recently there has been an additional method of finding a market for everything, and that is a well-

It was revived when the famous Cunarder Mauretania went to her last berth. Most people in Great Britain, and many people in the United States, were keenly interested in the old ship and an auction sale of all her furniture and fittings, lasting for several days, brought big prices. The ship herself was nearly thirty years old, but her furniture had been kept right up to date and as soon as there was any sign of wear it had been replaced by new.

AT NEWPORT, MONMOUTHSHIRE, the Cunard White Star liner Doric waiting to be broken up. The Doric was involved in a collision off the Portuguese coast in 1935 and her passengers were rescued by the Orion.

Obsolete men-

The modern routine is quite different. All the sales are conducted by private treaty and any question as to the price realized, whether it is raised in Parliament or outside, is always met with the statement that its divulgence would be against public policy. In spite of the change, the scrappers are still as eager as ever for any warship that is on the market. There is a big weight of steel in her hull, and the breaker can usually rely on getting 60 per cent of her displacement in heavy scrap, and 10 per cent in light scrap. The proportions vary with the type of ship. Brass, copper, lead and cast iron are also yielded in considerable quantities, and the carefully-

The Admiralty takes precautions against Service secrets being divulged by the sale of ships. All gear of a confidential nature, especially that connected with gunnery control, is carefully removed. A good deal of it will be useful in other ships, but almost the same care is taken even if it is obsolete and useless.

A Ship’s last Berth

After the Armistice there were hundreds of men-

Shipbreakers did well out of the business, but there arose a craze for scrapping and a number of mushroom concerns sprang up all round the British coast.

The price of a ship for scrapping is usually fixed at so much a ton gross for a merchantman and so much a ton displacement for a man-

The expert eye of the scrapper assesses her value remarkably quickly -

When there was a glut of steel on the market, and the price was depressed, many shipowners who were hard hit by the slump were obliged to sell their ships for as little as six and seven shillings a ton gross, about the lowest level in the history of the business.

As industry revived, so the price revived as well, the passenger ships being always just a little ahead of the cargo vessels. The £78,000 given for the Mauretania worked out at £2 10s 10d a ton, gross, and the £100,000 which was given for the Olympic was £2 3s 0d a ton. If £2 a ton gross is given for cargo vessels the market is in a flourishing state.

Shipbreaking is an industry which has grown vastly of recent years and has every chance of further expansion as the demand for steel appears to get bigger and bigger. To the lover of ships there is always something sad about a scrappers’ yard where a beautiful vessel is ruthlessly cut up into lumps of dead material.

UPSIDE DOWN IN DRY DOCK. The German battleship Konig Albert at Rosyth, Firth of Forth. This warship, completed in 1913, had a displacement tonnage of 24,120 and a speed of 21 knots. She had ten 12-

The photogravure supplement accompanying this article can be seen here.

You can read more on “Dramas of Salvage”, “Ship Surgery” and “The Ship That Broke Her Back” on this website.