© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Ship Surgery

After being wrecked off the Cornish Coast, the Suevic was salvaged and fitted with a new bow. She has since served for many years as passenger liner, troopship and whaling mother-

ONE of the most successful examples of “ship surgery” was the salvaging of the White Star liner Suevic. The cost of the work was more than justified, for the vessel is still leading an active existence. She was built by Harland and Wolff of Belfast in 1900, and was the last of a class of five begun in 1898. These ships were designed for the Australian service of the White Star Line. The Suevic was a fine-

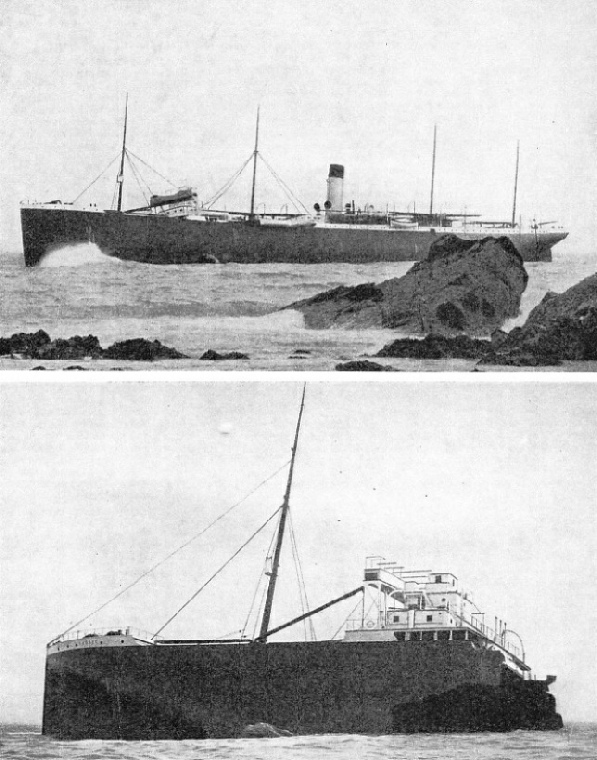

THE SUEVIC ON THE ROCKS. The upper photograph shows the liner on the rocks near the Lizard, Cornwall, where she struck on March 17 1907. Her bow as firmly held by the rocks, and in a few days the lower parts of it were reduced to a tangle of steelwork. It was decided to cut the ship in two, abandon the bow and salvage the remaining 400 feet of the vessel. This after section was perfectly sound and later was fitted with a new bow. The lower picture shows the damaged bow shortly before it was broken up by the sea.

When she was ready for service the Transvaal War was in progress; when her maiden voyage was advertised the Admiralty suddenly requisitioned her as a transport, so that her first trip was to the Cape with a few details and military stores, and then on to Australia with time-

After that she was released to her owners and, with her four consorts, maintained the regular monthly Australian service. This service was extraordinarily popular; its accommodation gave the settler of good standing the opportunity of travelling comfortably to Australia at a reasonable rate. The White Star Australian service developed on the passenger side a character of its own. The large cargo capacity of the ship was fully used, especially homeward bound.

In March, 1907, the Suevic was homeward bound from Melbourne and had already called at Cape Town and Tenerife, one of the Canary Islands. She was due to call at Plymouth to land the bulk of her passengers before going on to London to discharge and then round the coast to Liverpool, her home and port of sailing.

On March 17 she was making her landfall. A heavy blow from the southward and westward, raising a high following sea, had moderated and there was a gentle westerly breeze. Visibility was good but fog threatened. There was no difficulty in getting observations, which gave the Lizard Light 138 miles away. The ship followed her course at full speed of thirteen knots. At ten o’clock in the evening dead reckoning gave her as having covered 122 miles of the 138 without making allowance for the set of the tide, so that she should have been well within the range of a light as powerful as the Lizard. By that time the night was dark and thick, with showers of drizzling rain. The Suevic carried straight on.

At a quarter-

The captain wanted to get a four-

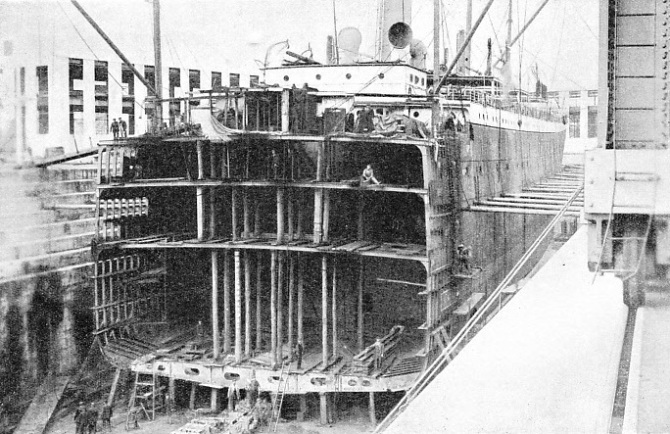

THE STERN OF THE SUEVIC being towed into Southampton Docks. The salvaged part of the ship included the engines, boilers and the bulk of the passenger accommodation. It was a difficult undertaking to cut the vessel in two, for in 1907 the use of the oxy-

At twenty-

There was no doubt they were close inshore and heading straight for disaster. The master immediately ordered the helm hard a-

The news that a big passenger liner was wrecked on the dreaded Maenheere Rocks spread rapidly. With little delay all the Royal National Lifeboat Institution lifeboats within reach went to the Suevic to assist. Passengers, were ferried ashore in the lifeboats and in the Suevic’s own boats, which were swung out and manned in perfect order. Steam tugs arrived soon afterwards and helped in the work. Most of the passengers were landed with the minimum of discomfort at the little village of Cadgwith.

Aid By Road and Rail

The Great Western Railway organized a fleet of motor-

The story of the Suevic is not unique. Similar accidents have occurred on iron-

This is a device with a quickly flicking light which gives the depth of water under the keel at any particular moment. In another form it traces out on a revolving roll of paper the exact contour of the sea bottom. The later vessel would also have submarine signalling apparatus, although this is not of such great advantage on an iron-

READY FOR THE NEW BOW. As soon as the stern of the Suevic was salvaged a new bow was ordered from Harland and Wolff, who had built the ship. The new bow was 212 feet long and extended to the after end of No. 3 hold, thus giving a slight overlap on the salvaged portion. The photograph shows the stern of the ship in dry dock at Southampton, where it was waiting for the arrival of the new bow.

The news of the disaster caused much excitement in Lloyd’s, as another passenger liner was wrecked on the same night. The White Star Company insured its own ships, but the underwriters were interested in her cargo, for it included butter, wool, wheat, frozen meat, rabbit skins, copper and other Australian commodities, valued at a high figure.

The salvage steamers Ranger and Linnet, former Navy sloops, were sent down from Liverpool, equipped for the work, and every available barge and coaster in the West Country was collected to receive the cargo. Holds Nos. 1, 2 and 3 were by then open to the sea, but the engine room and boiler room, and the holds abaft them, were still tight and dry.

By March 20 the sea had subsided sufficiently for the lighters and coasters to go alongside, and the ship was lucky to be able to have the full use of her own steam. The work proceeded rapidly and a close watch was kept on the weather; for as soon as the Atlantic rollers came in work had to be suspended. Happily, calms continued until the 27th, by which time all the sound cargo had been saved. Cargo to the value of about £40,000 was discharged every day, and the work was completed only an hour before the weather changed. A heavy swell set in, making it impossible for small craft to work alongside, and a dense fog nearly caused the wreck to be rammed by a passing vessel.

The next thing to be decided was what to do with the hull. It was obvious that the forward part was firmly held by the rocks and would defy all efforts to release it. In addition, the hull was like a sieve, for the swell, lifting the stern and letting it fall, had ground all the lower part of the bows into a tangled mass of steelwork. There were many who thought it was wisest to cut the losses and abandon the ship, but the men on the spot did not agree. Their plan was to cut the ship in two, as had been done a short time before with the Elder Dempster steamer Milwaukee.

Cutting Her in Two

It was a daring resolution for many reasons. The conditions surrounding the Suevic were much more difficult than those of the Milwaukee. The weather might at any time ruin all efforts. Operations on the Elder Dempster ship, too, although successful technically, had been a financial failure. A thorough examination of the wreck of the Suevic determined the salvage men to take the risk. The last compartment damaged was the coal cross-

The undertaking would present no great difficulty now, but at that time the use of the oxy-

The big ship was neatly cut in two just abaft the bridge, which in the Suevic, as in many Harland and Wolff vessels, was isolated from the passenger accommodation to give the officers as quiet a time as possible during their watch below. The swell, lifting the buoyant stern, finally helped to break the vessel in two, and the after part floated off on an even keel. The attendant tugs took hold at once and got the ship clear of the reefs; but their job was more to help in the steering than in the propulsion, for the engines and boilers were in full commission. The Suevic steamed stern foremost to spare any strain on the exposed bulkhead, which had naturally been weakened by the numerous explosions close to it. She made her way to Southampton where she was docked.

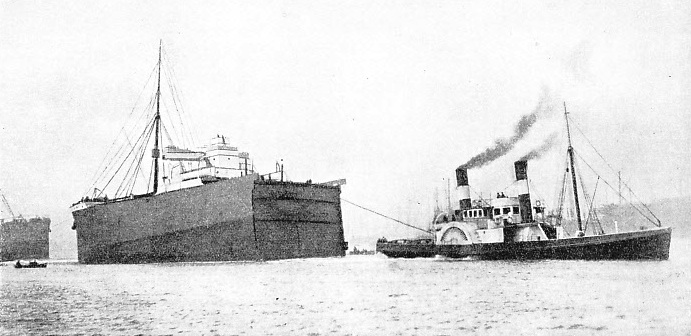

THE NEW BOW OF THE SUEVIC leaving Belfast on October 19, 1907, for Southampton. It was built on a slipway in the ordinary manner, but was launched head foremost. This unusual procedure was necessary as the bulkhead that closed the after end was not built to withstand a great pressure of water. The bow was towed by the tug Pathfinder, which is seen in the photograph, and steered by the Blazer. The journey from Belfast to Southampton took six days.

As soon as the stern was salved, the White Star Line gave orders for a new bow to be built at Harland and Wolff’s yard at Belfast, where they had the plans of the original ship. It was designed to be 212 feet long, extending to the after end of No. 3 hold to give a slight overlap on the salved portion. The bow was built on a slipway in the ordinary manner and launched head foremost. This was an unusual procedure in a British shipyard, but it was deemed safest, as the bulkhead closing the after end was not designed to withstand a big pressure of water. Bridge, boats and other details were attended to, and the bulkhead was strengthened. It was towed to Southampton bulkhead foremost by the tugs Blazer and Pathfinder. A special donkey boiler was installed, with powerful pumps to deal with possible leaks. These pumps were not used, although some bad weather was encountered in the Irish Sea. The bow left Belfast on October 19, 1907, and arrived at Southampton on the 25th, towed by the Pathfinder and steered by the Blazer.

A similar job of ship surgery was carried out on another occasion by Harland & Wolff at their Belfast yard, when the Royal mail liner Lochmona ran aground near the entrance to the Mersey and broke in two. Here again a new fore end was built and the technique which had been evolved at the time of the construction of the Suevic was again brought into action. The problem of building a new fore end is fairly simple provided that plans of the ship’s lines exist. It is much more difficult to launch a new bow and take it to its destination. It is necessary to launch the fore portion of the hull bow first. A bow naturally runs farther into the water than does a complete ship when launched stern on. The question of trim and stability is difficult, too, when dealing with an incomplete ship.

Outstanding Salvage Feat

Furthermore, the bulkhead which forms the “aft end” of this portion of the hull must be specially strengthened, and this factor may involve the completed structure in a certain amount of stress. Shipbuilders are notoriously versatile, however, and there are not many problems of this nature which cannot be satisfactorily solved.

When the Suevic’s new bow arrived at Southampton, the two sections were dry-

The ship thus salved and reconstructed was as good as ever she had been, and proved it. Between her salvage and the war of 1914-

In 1920 she returned to the Australian service and continued on it until 1928, when she was sold. Most of her sister ships had already gone to the scrappers, but her buyers, who gave £35,000 for her, had no intention of letting her end her days. She was converted into a pelagic-

Although the “surgery” on the Suevic would not, in these days, present so many intricate problems -

IN SERVICE AGAIN. The reconditioned Suevic lying at the Liverpool Landing Stage in August, 1925, after she had been in regular service on the run to Australia. During the war of 1914-

You can read more on “Dramas of Salvage”, “The Shipbreaking Industry” and

“The Ship That Broker Her Back” on this website.