© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Deep Sea Fishing

The sailing fishing fleets of fifty years ago have disappeared, but the British fishermen still carry on the traditions of their predecessors, though in conditions less exacting. The modern methods of deep-

DRIFTERS ENTERING YARMOUTH HARBOUR with their catches. Sometimes the vessels are loaded to sinking point; then there may be such a glut on the market that the herrings have to be taken back to sea and dumped overboard. Many suggestions have been made to prevent such waste of this valuable food.

A LITTLE more than fifty years ago the North Sea was swept by a storm in which 360 fishermen and fisher-

That disaster was known as the Great March Gale of 1883 and there are survivors who can thankfully compare things as they now are in deep-

That was the time of sail, when small ships were at the mercy of wind and sea. To-

Fifty years ago the smacksman was almost unknown to the public. He came from the poorest of homes, the workhouse, the reformatory, and often the jail. Miserable little apprentices who

for various offences appeared before magistrates begged to be sent to prison rather than back to fishing. The doghole of a cabin aft was the fisherman’s sole refuge all the time he was at sea, and that meant, if he were a fleeter, eight, ten or more weeks. He ate, drank and slept in this human kennel, often bug-

The fishing-

The man of sixty who had been fishing for fifty years was almost as much a part of the sea as the “prime” and “offal” out of which he made his poor living. Against his small earnings, however, was to be set the board and lodging at sea. Food, especially fish, was good and plentiful; but it might well be said that while Providence provided the food the Devil himself too often supplied the cooks in the form of dirty, incompetent men or small boys teaching themselves their trade.

Half a century ago a sailing fishing fleet was a familiar sight on the North Sea. Yarmouth alone sent out four fleets, carrying crews of about 2,800 men and boys in all. Five fleets went from Hull, several small and two large fleets from Grimsby and two fleets from Lowestoft. Other ports contributed fleeters.

A total of 10,000 men and boys were fleeting in the summer. That number was reduced in winter, when many of the smacks were single-

One of the most dangerous features of the fleeting was the ferrying and boarding of the catches —pulling the smacks’ boats across the exposed sea and getting the heavy boxes, or trunks, on board. On one February morning alone, in one fleet, seven men were drowned through their boats capsizing, and in another fleet two were lost — nine altogether.

Ten thousand men and boys were afloat on the North Sea, far from land and all its comforts. Of the men most had spent almost all their lives on the water and they knew nothing of enjoyment and recreation except indulgence of the basest sorts. Drink at sea and on land was the general resort. Ashore there were numberless and almost uncontrolled public-

What the “coper” meant was tragically indicated by a skipper who said, “Many’s the smart smack ’at’s been lost through him, many the home that’s been ruined, an’ many the life that’s been lost. Time after time I’ve spent my last penny on board the old Dutchman, an’ when we’d no money left I’ve seen boatloads of gear ferried to him from the smacks to swap for drink. He did a roarin’ trade in the old sailin’ days, when for days together smacks couldn’t fish because there wasn’t any wind.”

Foreigners were not the only offenders. Smacks sailed from England, apparently to fish; but they made for Dutch ports, stowed their gear and took on board as much as £500 worth of spirits and tobacco. A smack would then rejoin her fleet and in one voyage of two months would dispose of her cargo and make a profit of £500 on it.

Such was the state of things when a sudden change for the better came. Sail trawling had reached its zenith and the old order passed completely. The “copers” were swept from the seas bv the ships of the Royal National Mission to Deep Sea Fishermen, which supplied duty-

Just when the sailing period had reached its highest development, steam came in as conqueror. Experimental paddle tugboats, fitted with beamtrawls, as were the smacks, proved their superiority over sail. These squat craft were soon replaced by screw trawlers, and as this type proved successful, it was adopted for use in the fleets as well as in single-

Steam Trawler Fleets

Gradually there has been evolved the splendid fishing vessel for which to-

When smacks were superseded, four fleets of steam trawlers came into existence. The fleets were the Red Cross, Gamecock, Great Northern and Hell-

When smacks were superseded, four fleets of steam trawlers came into existence. The fleets were the Red Cross, Gamecock, Great Northern and Hell-

OFF TO THE FISHING GROUNDS. There are only a lew survivors of the smack that depends solely on sail. Here is a Lowestoft trawler going to sea. The beam of the old-

The youngest fleet was Hellyers', established in 1906 and consisting of seven carriers and fifty-

After the war two fleets were gradually reassembled; but economic conditions made it necessary to amalgamate them. Then came the time when the fleeting system proved unprofitable, and the two companies that controlled it went into voluntary liquidation early in 1936. Exceptionally bad weather, the rising price of commodities, especially coal, of which the companies used 100,000 tons yearly, lessening supplies of fish, and growing competition — all these were factors in the closing down. Sixty fleeters were concerned, and about 800 men in Hull, the headquarters of the fleet. In addition there were porters at Billingsgate, salesmen and office staffs. An old fleeting skipper described the liquidation as “a most terrible disaster for Hull.”

The fleeting system was for a long period one of the chief features of deep-

Admiral of the Fishing Fleet

When the smacks were displaced by the steam trawlers the fleeting system remained the'same. The fleet was controlled by an experienced fisherman called the admiral, with whom was a vice-

Sometimes a carrier would bring to market nearly 3,000 boxes of fish, a box or trunk weighing about 80 lb. In one fleet of 130 smacks a day’s fishing totalled 2,865 boxes. With the exception of 139 boxes of “prime”, turbot, soles and the like, all the boxes contained “offal” — haddocks and similar inferior fish. Too often the offal when sold at Billingsgate did not pay for the cost of carriage from the fleet, and there was nothing for the fleeter’s toil in getting the fish.

The steam trawlers which composed the fleets were mostly small and old. A typical vessel was forty years old, of 41 nominal horse-

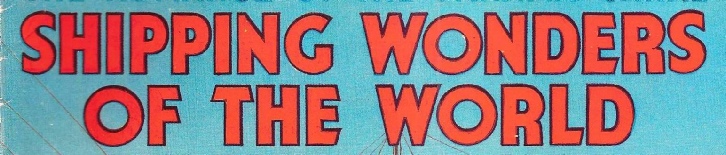

LANDING BARRELS ON THE QUAY AT YARMOUTH (Norfolk). These barrels are used for packing fish for the export trade. In 1934, some 114,837 tons of herring were landed in England and Wales and were estimated to have had a value of £759,986. Since the war of 1914-

To-

A good example of the latest singleboater is the Stafnes, said to be the heaviest and strongest British trawler afloat. She comes from the yard of Cochrane & Sons, Ltd., Selby, Yorkshire, and is owned by the Rinovia Steam Fishing Company, Ltd., of Grimsby. Special efforts have been made to ensure the safety and comfort of the crew. The Stafnes is 162 feet long.

In the forecastle, which is big and airy, there are twenty-

The skipper’s room is on the same level as the wheelhouse, which he can reach in two seconds — a great help in emergencies. Beneath his room is the wireless operator’s cabin, which is equipped with telegraph, telephone and direction-

There, too, is the skipper’s bathroom, with a shower-

Single-

Wireless in British fishing vessels is essentially a post-

There are even larger trawlers than the Stafnes, and all the principal fishing ports are adding to their big type craft. The chief fishing port on the west coast — Fleetwood (Lancs), famous for hake — is being provided with no fewer than fifteen large new steamers, each with a length of 184 feet. Hull and Grimsby are following the same policy and Aberdeen and Milford Haven (Pembrokeshire) hold their places.

These are the fishing vessels that go to high latitudes and out into the Atlantic, single-

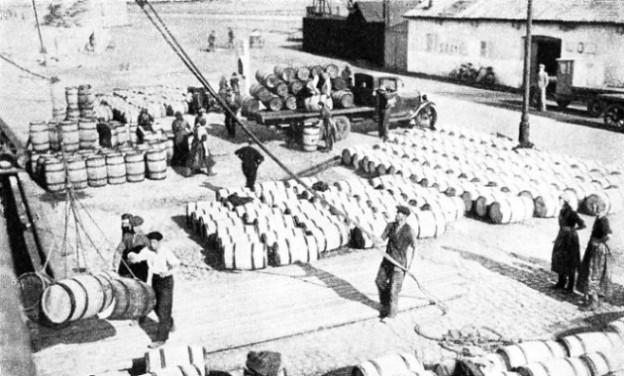

There are four methods of deep-

CONVERTED PADDLE TUGS, mostly from the Tyne, were the earliest steam trawlers. They were fitted with beam-

Of the four methods, trawling is by far the most laborious and hazardous. The drifter and the seiner work mostly within easy reach of port. The long-

Bear Island, for instance, is about 400 miles within the Arctic Circle, on the edge of the ice drift. The seas freeze as they come on board, the fish freeze when they drop from the net, and the winch has to be kept running to prevent freezing. The work is ceaseless and no such thing as real rest and sleep is known until the catch is complete, the fish-

Those conditions apply to trawlers working in high latitudes, but the strain is almost the same wherever the trawler goes. Her trip may be short — five or six days — or long — four weeks or even more. The time spent ashore between trips may be forty or forty-

In trawlers especially there is always danger from warps, nets, blocks, bollards and so on, and the motion of the ship. Terrible accidents occur from snapped wire warps and the sudden tremendous strain on ship and gear due to bad weather; and there are sea-

A Mile of Nets

The drifter is much smaller than the trawler, though she is far bigger to-

During the herring season at Yarmouth as many as 1,000 drifters will be assembled, and there have been times when the River Yare was so closely packed that one might have walked across it from bank to bank, stepping from ship to ship. The same congestion was not uncommon at Scarborough formerly, when the inner harbour on a Sunday would be a solid mass of Scottish sailing luggers.

THREE PRINCIPAL METHODS OF DEEP-

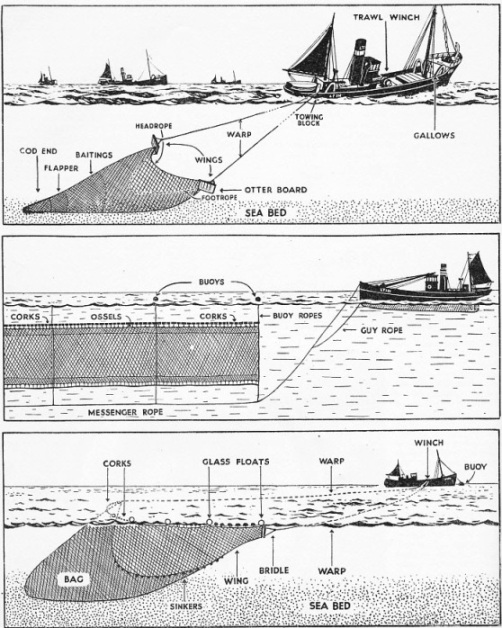

One familiar sight during the herring season is the fisher-

A drifter carries nets enough when fastened together and suspended in the sea to make a wall a mile or more long and several yards deep. The upper edge, called the back, has a great number of corks which keep the nets upright. To give the necessary buoyancy, floats of various types are used. The nets are shot over the quarter just before sunset, while the vessel goes slowly along. When all the nets are overboard the swing-

This method of drifting has been employed probably for many centuries. Old Lowestoft fishermen believed that the method had remained unaltered for about 1,000 years and that the nets had been of almost the same design throughout that period.

Seine fishing has made great progress in home waters since its introduction some years ago. The system, which is Danish, is specially suitable for drifters, small trawlers and motor-

THE HERRING SEASON IN FULL SWING. Drifters unloading their catches of herring at Yarmouth. When the fleet is in the harbour the vessels are sometimes so tightly packed side by side that they almost block the River Yare. The baskets in the foreground, of double pannier shape are peculiar to Yarmouth They are called “ swills.” The basket is made of unpeeled willow and will hold about 500 herrings. It was formerly used to transfer the fish from the boat to the shore.

The great line fishing is a most interesting industry. Apart from the vessels specially engaged in it, there are others which have been turned for the time being into liners — a drifter, for example, which because of the poorness of the herring fishing has gone into lining in the hope of success. In such a vessel not long ago were five relatives — the skipper, his son, his brother and two nephews. With that close relationship it is tragedy indeed when a fishing vessel is reported lost with all hands.

When the great lines are all out they will stretch on end for about nine miles. The hooks are baited with mackerel or herring and suspended about 9 feet by a smaller cord or snood from the main line, at intervals of about 20 feet along the entire length. The hooks are baited as the line passes overboard. In fine weather three or four hours pass between shooting and hauling.

The Highly Prized “But”

The hauling is the most interesting and anxious of all the operations. It is joyful to see a good haul of hooked fish; yet too often the haul is ruined by the attacks of dogfish, or worse still, of sharks. A big and valuable fish will be swooped upon by a monster whose powerful jaws sever the line with a vicious snap.

The fish most highly prized by the long-

British fishing craft alone, apart from the fishing vessels of other countries, form one of the most interesting ship types in the world. There is not, however, the same variety as before the war of 1914-

The sailing fishing vessels were as different in their names as they were in rig, and a few are still almost the same as they were in the days of the Norsemen. The Shetland big open boat known as the “sixern” closely resembles the Norsemen’s long craft, and the Yorkshire cobles keep true to an extremely old type.

Sail alone has almost vanished. The smallest of craft has its motor, and steam and internal combustion engine continue the fight for mastery in the biggest craft. Steam is still a firm favourite. The single propeller too has yet to be beaten by twin or more screws.

To-

All this improvement is as it should be, for the deep-

AN IMPORTANT PART OF THE INDUSTRY. Scottish girls busy gutting herring at Yarmouth. The girls work in crews of three and are Astonishingly skilful with their knives. An expert will gut or “gip” at the rate of a herring a second. The gutted herrings are packed in brine in the barrets shown and are exported to the Continent. These herrings are mostly eaten raw.

You can read more on “The Fishery Patrol Ship”, “Fishery Protection” and “His Majesty’s Customs Service” on this website.