© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Fishery Protection

It is the duty of the Fishery Protection Service to see that British and foreign fishing vessels abide by the regulations and restrictions governing the fishing grounds. After an offence against territorial laws, however, fishermen will often run considerable risks to avoid arrest

THE BLACK-

.

THOSE who remember the sailing fleets and the earliest of the steam fleets in the North Sea will recall three craft which, though more or less with the fleet, were no business part of it. One was the “coper”, or floating grog-

The coper dealt in her poisonous drinks until she was driven off the waters. She is now only a piratical memory. The mission ship survives and prospers. The “Government boat” is more active than ever and. with her allies, gives a real spice of adventure to the officers and men who form the crews, for the “Government boat” is the policeman of the Narrow Seas.

Let it be said at once that the policemen are sportsmen and that most of the captives are sportsmen too. There is a constant game of catch-

The waters round Great Britain, especially the North Sea, bear swarms of fishing vessels and thousands of fishermen. The coast-

As it is on land, so it is at sea. The constable has passed a certain point. In comes the wrongdoer and works his will. At sea the Fishery Protection vessel acts in the manner of the constable. The poacher slips into forbidden waters and, though sometimes caught, he often escapes. Most of the instances which are made public are of wrongdoers who become the lawful prey of the Fishery policemen.

Except for small craft, the sea within three miles of the coast is forbidden to fishermen. There is plenty of space outside the three-

There are regions which are uncommonly tempting to the illegal trawler, places where he can get his gear down with a good prospect of making a fine haul or, in the event of an alarm, of escaping. One of them is Broad Bay, the principal fishing area of the island of Lewis, in the Hebrides. That locality suffers much from illegal trawling. It is particularly easy for trawlers to operate within the three-

The risks of poaching are great, but so are the rewards, and there is always the possibility of getting the benefit of the doubt of being in territorial waters. That chance is slight, however, for the Fishery Protection Officer is an astute being and is careful to be well on the right side before making an arrest.

Of the temptation to the poacher there can be no doubt, especially in the Moray Firth. Into those waters off the east coast of Scotland foreign fishermen may go and trawl at will and with safety, but the British fishermen are forbidden. Naturally, therefore, they have a bitter grievance and will run great risks to trawl a catch in the Firth.

The hardship of the Moray Firth restrictions is shown when British trawlers run into the Firth for shelter. There is a recent instance of twenty-

Sea poaching is universal. British fishermen will raid forbidden waters, foreigners will make forays into British protected areas and scoop up all they can get. Ill feeling inevitably results. Only recently Thames Estuary fishermen complained strongly of poaching by French fishermen within the three-

Icelandic waters offer the most alluring bait for illegal fishing. In those high latitudes the penalties are exceptionally severe, and they are often imposed. The skipper of a Grimsby trawler not long ago was fined £1,046 on a charge of illegal fishing. That heavy sum represented the amount of the fine, plus the value of the gear, which was confiscated according to custom.

Compare that penalty with fines of £100 and £66 imposed on two French skippers for fishing within the three-

Heavy penalties may be enforced, but they will not deter some skippers from trying their luck at poaching. It is claimed on behalf of trawler owners that they are against illegal trawling and do all they can to prevent it. The local insurance company which insures nearly 90 per cent of the Fleetwood vessels resolved to suspend any skipper who was convicted of illegal trawling, and several of that port’s skippers have been suspended on that account.

A Formidable Fleet

Some of these poaching encounters demand all the resource, courage and discretion of officers and men on Fishery Protection duty, and especially of members of the Royal Navy. In 1933 the commander of the Cherwell came one night upon no fewer than twenty vessels all fishing within the three-

There are three Fishery Protection sloops -

The Cherwell and the other gunboats are of the trawler type, the Cherwell being of 665 tons displacement, 324 tons gross and 550 horse-

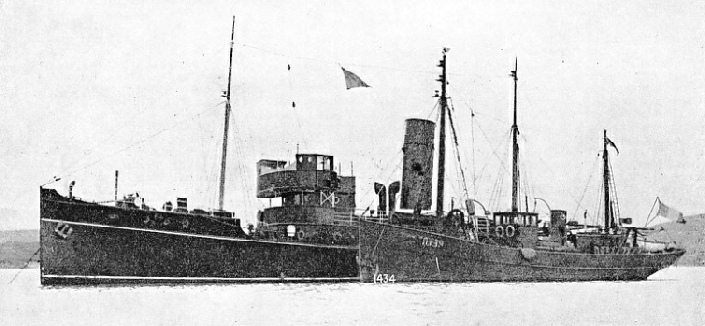

A CAPTURED BELGIAN TRAWLER, the Jeannette, alongside the Irish Fishery Protection cruiser Muirchu. The Jeannette was arrested for a contravention of the Fishery regulations. The Muirchu was built at Dublin in 1908 as the Helga. Of 323 tons gross, she has a length of 155 ft. 7-

In addition to these ships there are those of the Fishery Board of Scotland, of the Fishery Board of Ireland and of local bodies. The object is to establish a complete protective patrol, but that perfection cannot be gained There is a certain section of the fishing community, perhaps 10 per cent, which is as much a source of constant trouble to the Fishery authorities as chronic wrongdoers ashore are to the police. A wide net is thrown out, but the sea poachers are far more difficult to catch than the fish from which they make their living.

Remarkable instances of sea poaching come into court and show that Fishery officers must be good seamen, first-

A Defiant Skipper

In August 1931 Captain William Angus, of the Scottish Fishery cruiser Norna, was instructed to search for a trawler which had been reported poaching off the Butt of Lewis. The Norna arrived there at 11 pm and saw the trawler at work about half a mile off the land. She was not showing the regulation fishing lights It appeared to be an easy red-

Continuing his course, the captain of the Norna switched on his searchlight. Then the trawler was revealed with her gear down, being, according to the bearings taken at the time, a mile and a quarter from the shore.

The trawler was hailed through a megaphone, but there was no reply. Some men were moving about her deck and one of them was seen to enter the forecastle and return with an axe. With that weapon he began to cut the trawler’s warp. The captain called upon the skipper to stop his vessel and heave his trawl on board, as the cruiser was sending a boat with a boarding party. The trawler’s defiant answer was to cut her gear adrift and make off at full speed. Instantly the cruiser followed in chase, and for nine hours she hung on to the stern of the runaway.

The night was full of excitement tor both parties. Signals were made to the trawler, but she scorned to notice them. Meanwhile her people had been busy with disguise. Part of her number had been covered with oil or paint, and her lifebuoys either had been reversed or did not bear her name.

At eight o’clock in the morning a bank of fog was seen and into this the trawler headed with the cruiser only a length astern. The chief officer, who was in the cruiser’s bow, suddenly shouted that the trawler was going to port. Instantly the cruiser’s engines were reversed. Even so, her bow touched the trawler’s port side -

Still steaming full ahead the trawler drove into the fog and before the cruiser could regain speed she had disappeared in the protecting thickness. The chase ended in temporary triumph for the runaway, but later the cruiser’s captain identified her.

He saw the skipper, who frankly admitted that he had trawled illegally, that he had obstructed the Norna in the discharge of her

lawful duty, that he had concealed his registration number and that he had failed to show his regulation lights; but he denied that he had been guilty of reckless navigation in swinging his ship across the cruiser’s bows without warning.

The skipper, the mate and the second hand of the trawler were charged at the Sheriff Court. As to the skipper, his story was that he was fishing six miles off the land, when the Norna bore down on him, switched on her searchlight, and the captain shouted, “I charge you with illegal trawling.”

“But in point of fact you decided to run for it?” said counsel for the prosecution.

“Yes,” replied the skipper, “because I’ve never heard of a trawler charged by the commander of a Fishery cruiser getting clear of the penalty.”

“You were afraid of that?”

“Yes, because I’m only a chap, and I thought if I was I would suffer in my position.”

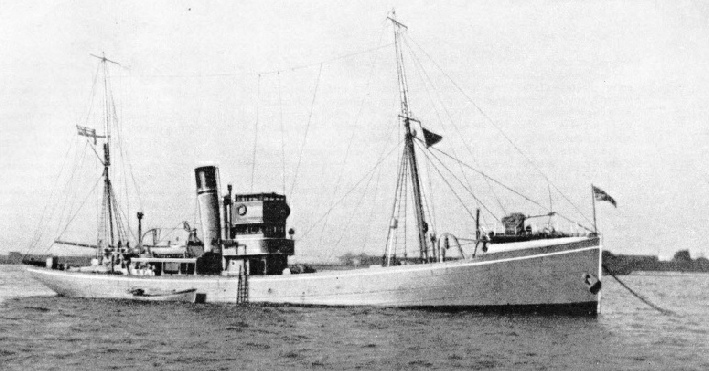

ON FISHERY PROTECTION DUTY at Yarmouth, Norfolk. The Daisy, used as a minesweeper and a surveying vessel before transfer to the Fishery Protection Service, was built at Aberdeen in 1912. Of 248 tons gross, the Daisy is 125 ft 3-

The skipper alone was found guilty. He was ordered to pay the maximum fine of £100 for illegal trawling, or go to prison for sixty days. He was fined £10 for concealing the name and numbers of his ship and £10 for failing to show the regulation night fishing lights -

Strange though that adventure was, yet it was exceeded in incident by another affair in August, two years later. Here are the elements of a real melodrama, not merely a chapter of happenings -

Once more the Norna was the cruiser, Fleetwood again supplied the object of the chase and Stornoway the scene of the trial. There were four charges against the skipper -

At two o’clock in the morning the Norna came upon two trawlers near Port of Ness, in the north of the island of Lewis. She approached the nearer of the two, turned on her searchlight and saw that the trawler was hauling her gear. The searchlight failed for a few minutes and when it was again turned on the trawler was seen to be making off at full speed.

A chase was then begun which lasted twelve hours. The trawler and cruiser went south until the Stornoway herring fleet was sighted at Chicken Head. Then the trawler turned north, rounded the Butt of Lewis and continued her flight to the west.

It was a lively chase. First the cruiser by searchlight signalled for the trawler to stop. No notice was taken of the signal. Two blank shots had no effect, nor was any attention paid to the Fishery Board’s ensign and a flag signal which were hoisted calling upon the trawler to stop.

During the chase the trawler’s registration numbers were covered with oil and it was seen from the cruiser that the covering was from time to time renewed. The funnel marks were also obliterated and the ship’s bell and the builder’s name-

A sketch was made of the trawler, three photographs were taken by the second officer, and peculiarities and defects were noted. The trawler had a funnel with a black top, and a lifeboat of yellowish colour. At three o’clock in the afternoon the cruiser came up with the trawler, and it was then seen that the sun had melted the oil on the numbers and they were visible.

“I’m going to leave you,” the captain of the Norna shouted, “and before I go I’m going to charge you with four offences.”

Ready to Repel Boarders

The only reply was the waving of a hand from the trawler’s wheelhouse. But the cruiser had seen enough for her purpose. The trawler’s crew showed sinister signs of repelling boarders, because boathooks were passed up on deck, and a steam hose was on deck. Those preparations did not suggest a hospitable reception.

When the trawler was afterwards seen at Fleetwood the yellowish boat was not there. She was said to have been lost during the run from the Minch to Fleetwood. In her place was a perfectly new white boat. The funnel was daubed in places with red lead, and several of the movable fittings had been taken away; but the essential identification-

Of the three photographs, one showed the numbers concealed and another showed one of the trawlermen renewing the covering. When at the trial the second officer was asked about the renewal picture he admitted that a person seeing it by itself might conclude that it was merely somebody seasick.

The Sheriff held the four charges proved and ordered the skipper to pay fines amounting to £185 or go to prison for three months.

The Fishery Protection Officer has many calls upon him, which he meets patiently and helpfully. Not all the requests are reasonable.

The commander of a Fishery gunboat had finished a trying spell at sea amongst the herring fleet. As a climax he had been called four times by drifters. Three were Dutchmen and wanted black draught for sick men or to be told their positions. The fourth occasion was a dispute between two boats as to sea-

The homeward run was being joyfully made when there came another summons from a Dutchman. His wants were unknown, but they had to be heard, though that might mean the loss of a tide and delayed arrival in harbour. The Dutchman merely wanted to have his wireless repaired.

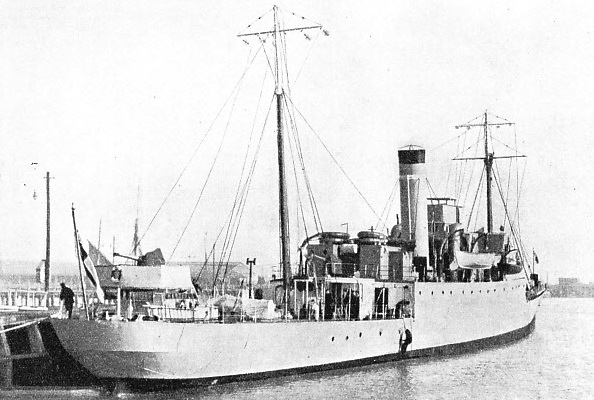

THE FLAGSHIP of the Fishery Protection Service is HMS Harebell, a sloop with a displacement of 1,345 tons. Built in 1918, she has a length of 250 feet between perpendiculars, a beam of 35 feet and a draught of 12 ft 6-

You can read more on “Deep Sea Fishing”, “The Fishery Patrol Ship” and “Grimsby -